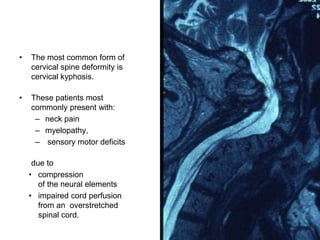

Cervical spine deformities can negatively impact quality of life through pain, neurological deficits, and impaired function. Cervical kyphosis is the most common deformity, presenting with neck pain and myelopathy. Deformities are classified as fixed or reducible. Surgical treatment depends on deformity flexibility and may involve anterior, posterior, or combined approaches to correct deformity, decompress the spine, and fuse vertebrae to maintain correction. The goals of surgery are to restore function through deformity correction and preservation of spinal alignment.