The document provides instructions for completing a case study in a business course, emphasizing the importance of a systematic training needs analysis (TNA) in designing effective training programs. It discusses a scenario at Westcan Hydraulics, where the HR manager, Chris, is tasked with developing a training package without conducting a TNA, highlighting the potential pitfalls of this oversight. The text outlines the TNA model and its relevance in identifying performance gaps and aligning training with organizational needs.

![BUSI 444Case Study Instructions

The answers to each Case Study must be 3–5 pages and

completed in current APA formatting. Your response must be

written in essay form, including an introduction, body, and

conclusion. Your Case Study response must be supported by at

least 2 scholarly, peer-reviewed articles. These sources must

have been published within the last 5 years. The Noe textbook

must also be incorporated but no other textbooks may be used.

Prompts:

Case Study 3: Module/Week 7: Career Development at

Electronic Applications

Complete "Career Development at Electronic Applications" case

in the Nkomo, Fottler, and McAfee text (#51, p. 157). Answer

the 6 questions (1–6) on p. 158. You may find it useful to use

the topic of the questions (The problem at EA, Relevant

information to be examined, etc.) as section headers in your

paper.

Textbooks for reading:

Human Resource Management Applications: Cases, Exercises,

Incidents, and Skill Builders - 7TH 11

by: Nkomo, Stella M.

https://mbsdirect.vitalsource.com/#/books/9781305990814/cfi/6/

2[;vnd.vst.idref=M1]!](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/busi444casestudyinstructionstheanswerstoeachcasestudymu-221031163259-4f26738a/75/BUSI-444Case-Study-InstructionsThe-answers-to-each-Case-Study-mu-docx-1-2048.jpg)

![Employee Training and Development - 7TH 17

by: Noe

https://mbsdirect.vitalsource.com/#/books/9780077774547/cfi/6/

26!/4/2/6/[email protected]:75.4

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, you should be able to:

· ■ Describe the purpose of a needs analysis.

· ■ List and describe the steps in conducting a needs analysis.

· ■ Explain what a competency is and why it is useful.

· ■ Differentiate between proactive and reactive needs analysis

approaches, and describe the situations favoring the use of one

over the other.

· ■ Outline the rationale for using performance appraisal

information for a needs analysis, and identify what type of

performance appraisal method is appropriate.

· ■ Describe the relationship between needs analysis and the

design and evaluation of training.

· ■ List four contaminations of a criterion.

CASE DEVELOPING A TRAINING PACKAGE AT WESTCAN

Chris is a human resources (HR) manager at Westcan

Hydraulics, and Irven, the VP of HR, is her boss. One morning

Irven called Chris into his office. “I just saw an old training

film called Meetings Bloody Meetings starring John Cleese,” he

said. “It deals with effective ways of running meetings.” Irven,

a competent and well-liked engineer, had been promoted to VP

of HR three months earlier. Although he had no HR expertise,

he had been an effective production manager, and the president

of the company had hoped that Irven would provide a measure

of credibility to the HR department. In the past, employees saw

the HR department as one that forced its silly ideas on the rest

of the company with little understanding of how to make those

ideas work.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/busi444casestudyinstructionstheanswerstoeachcasestudymu-221031163259-4f26738a/75/BUSI-444Case-Study-InstructionsThe-answers-to-each-Case-Study-mu-docx-2-2048.jpg)

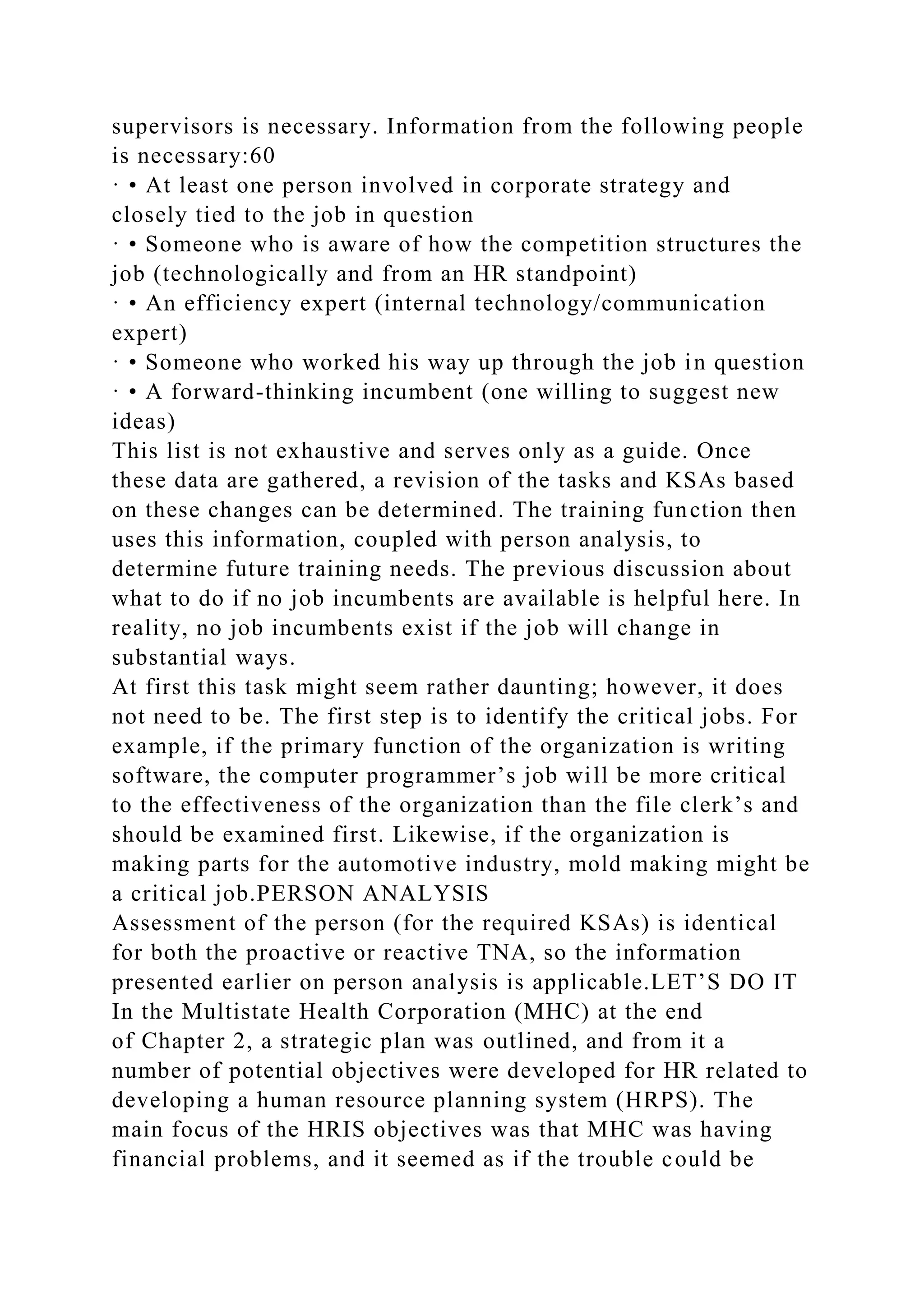

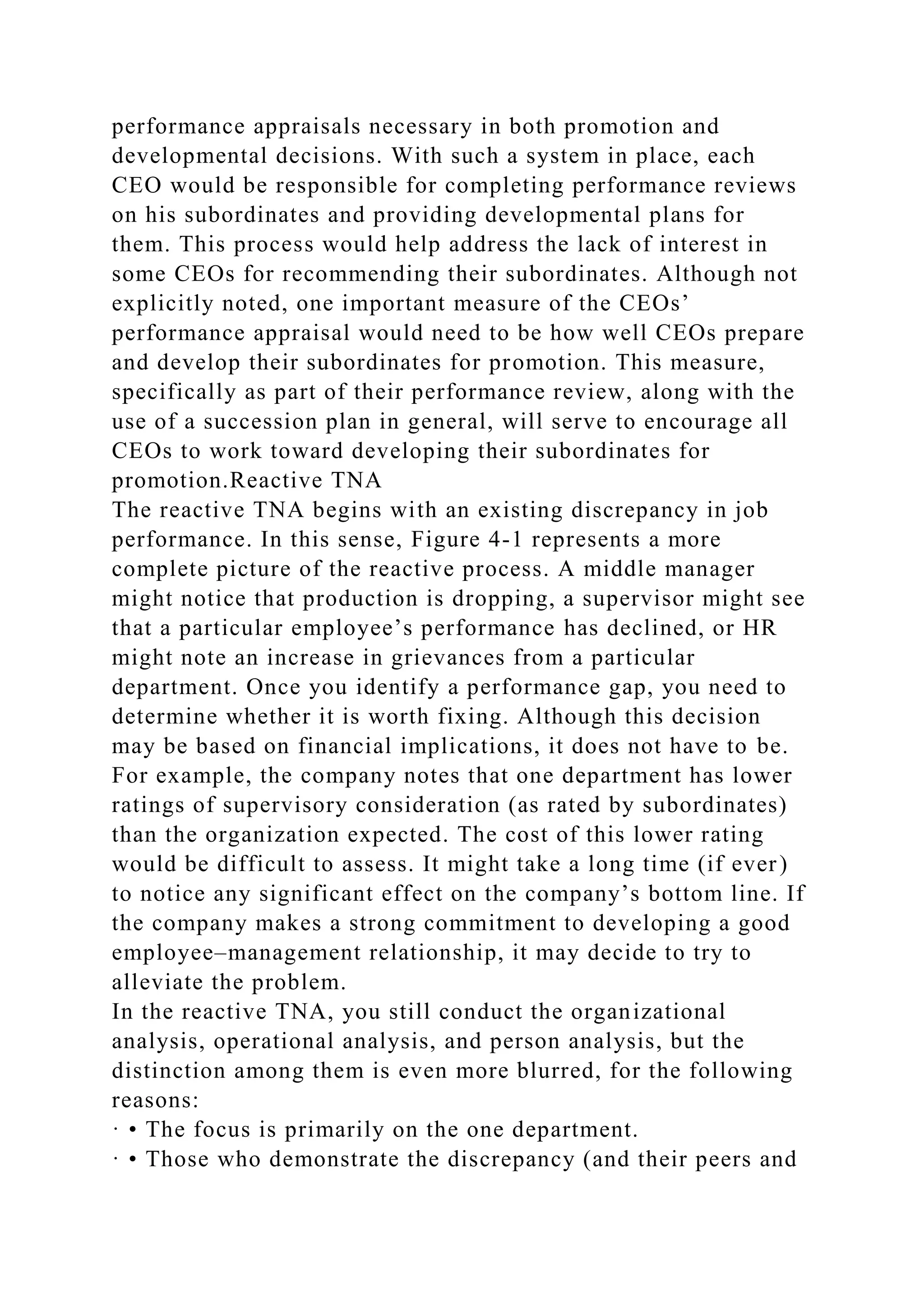

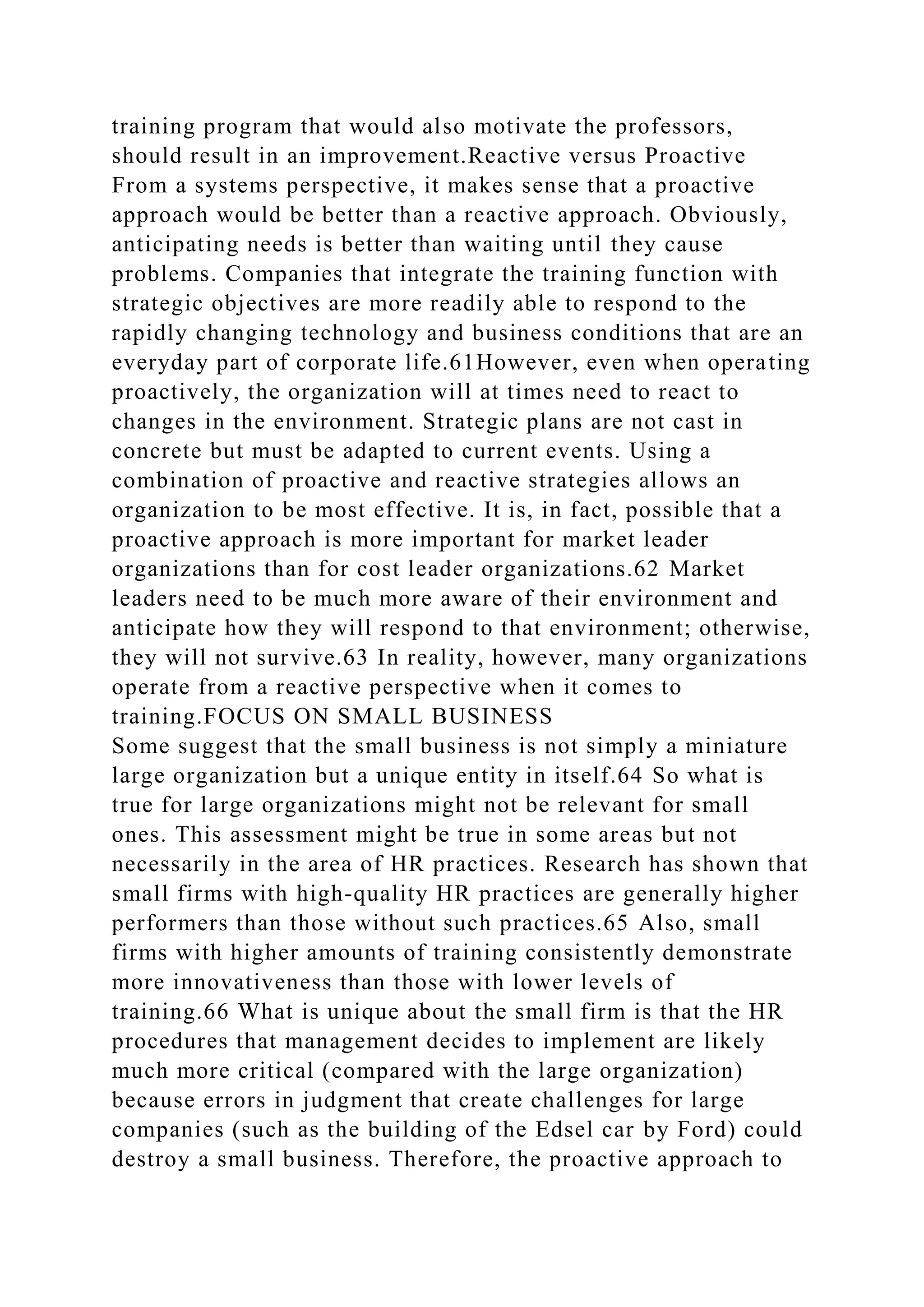

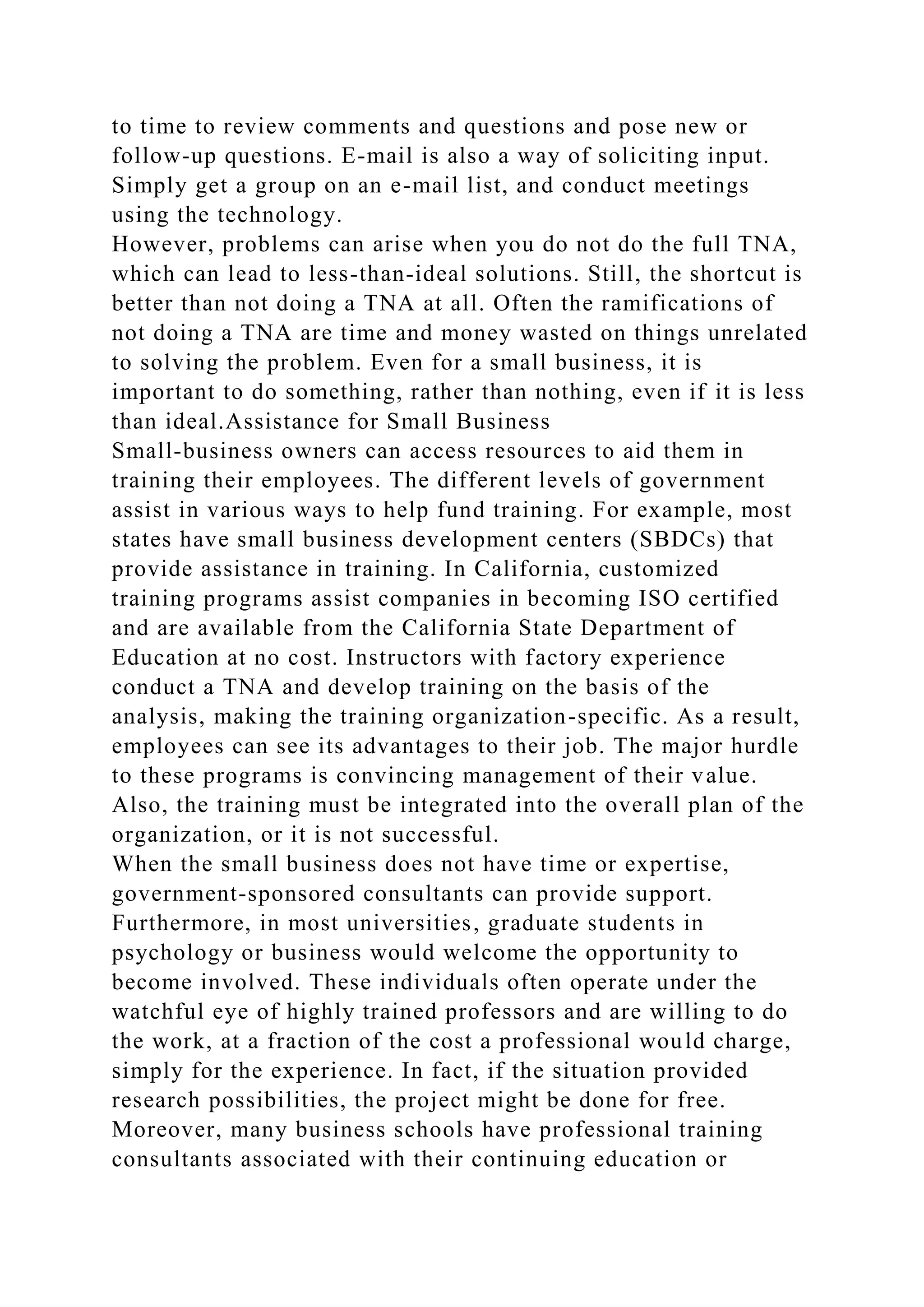

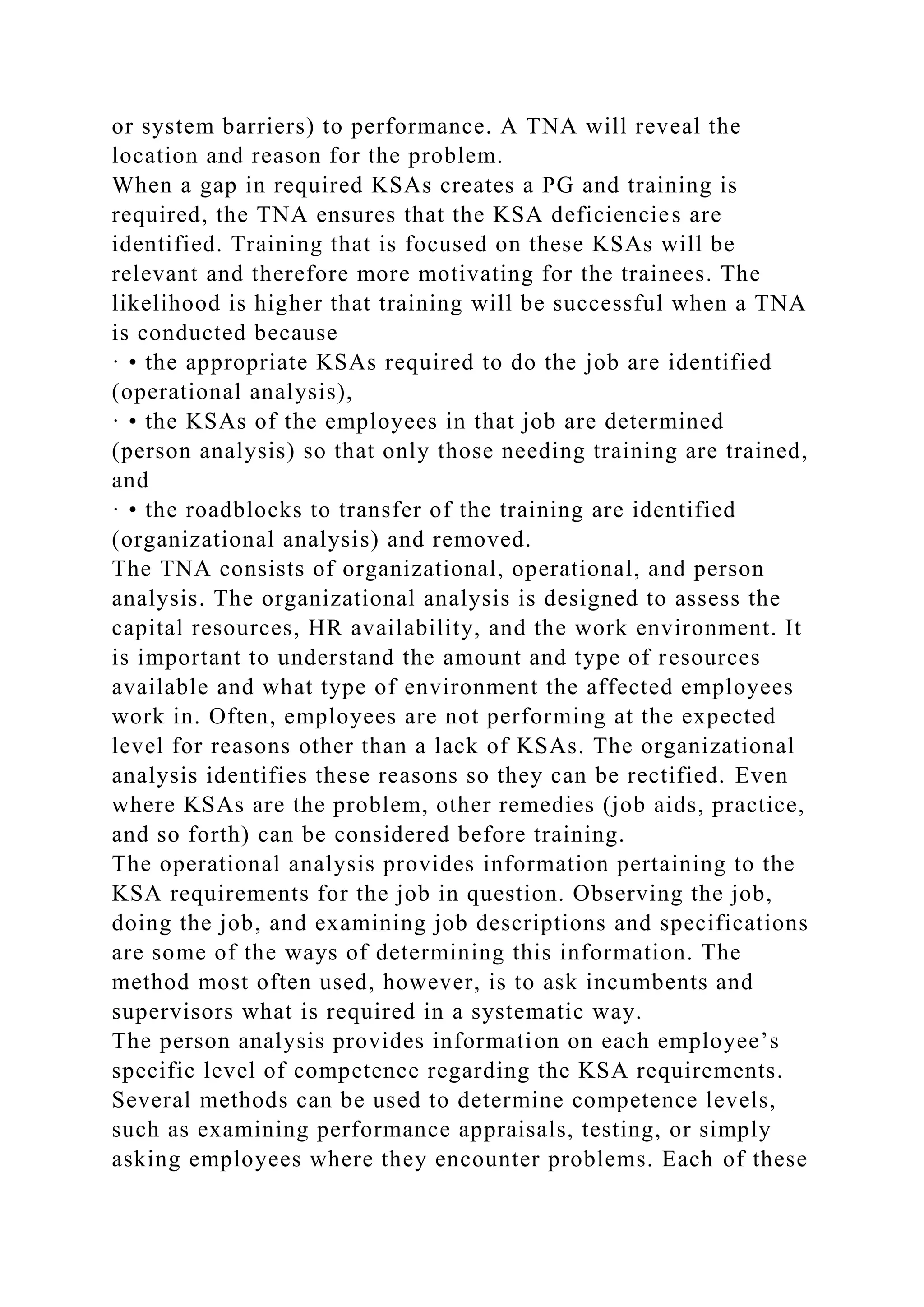

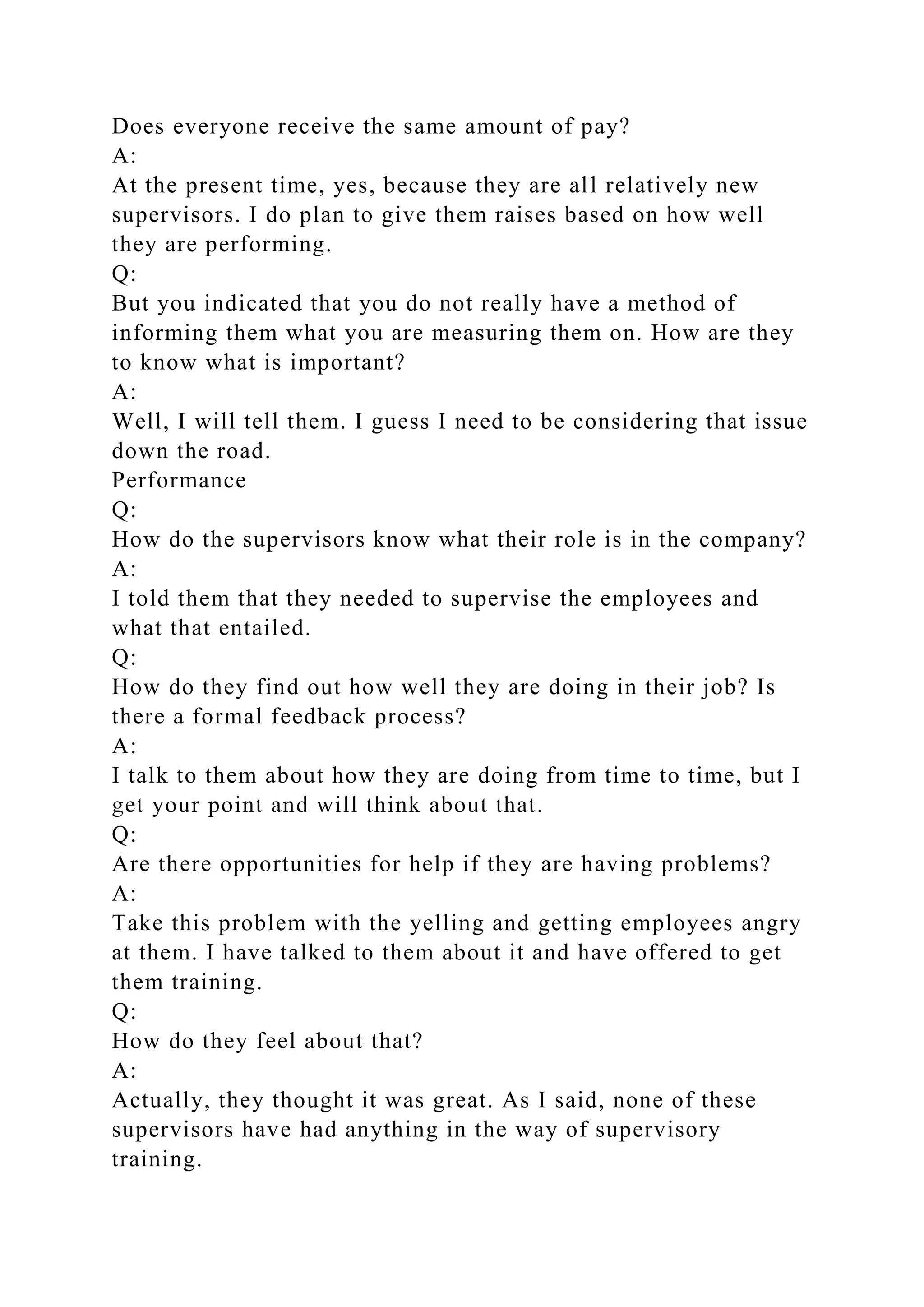

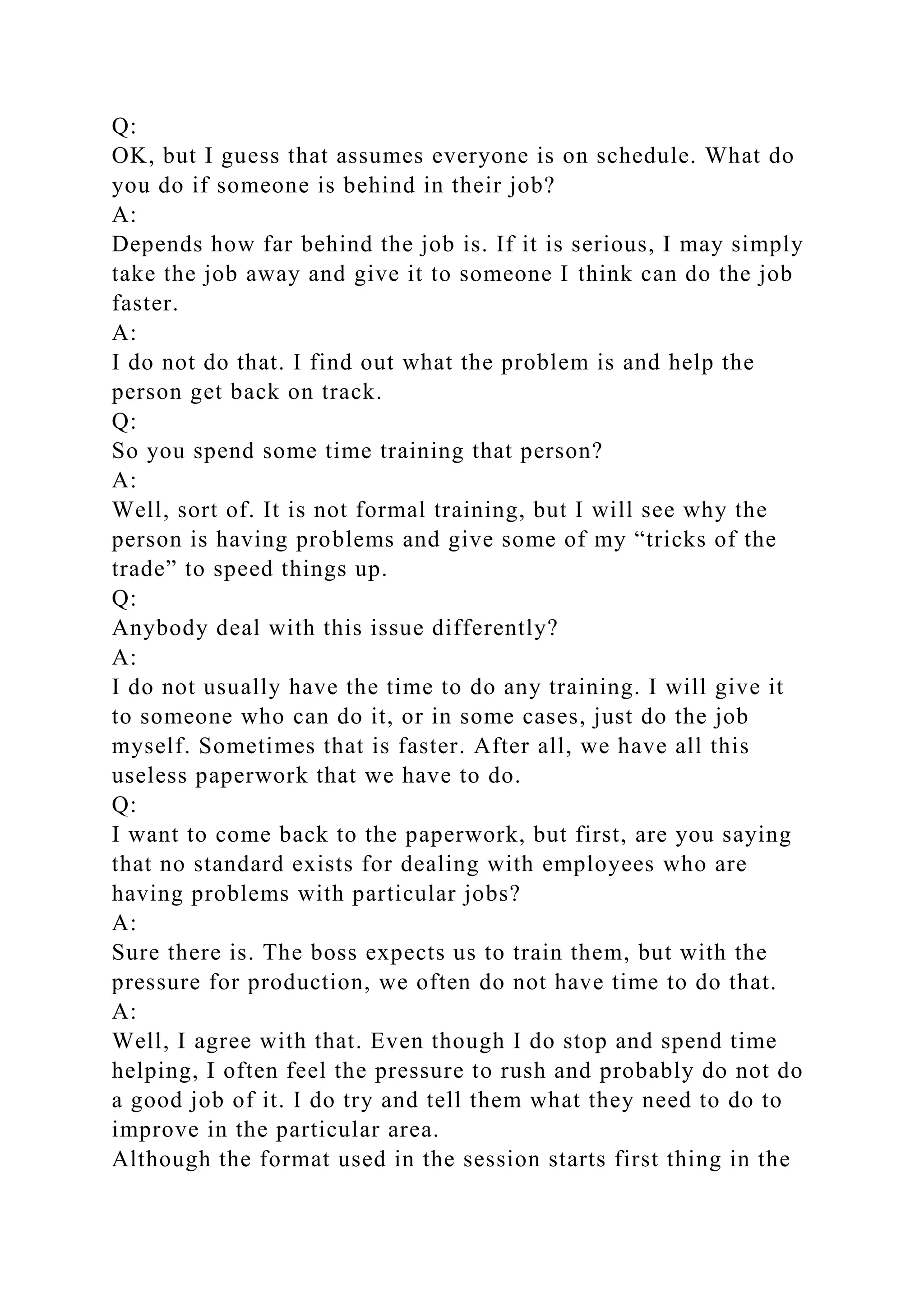

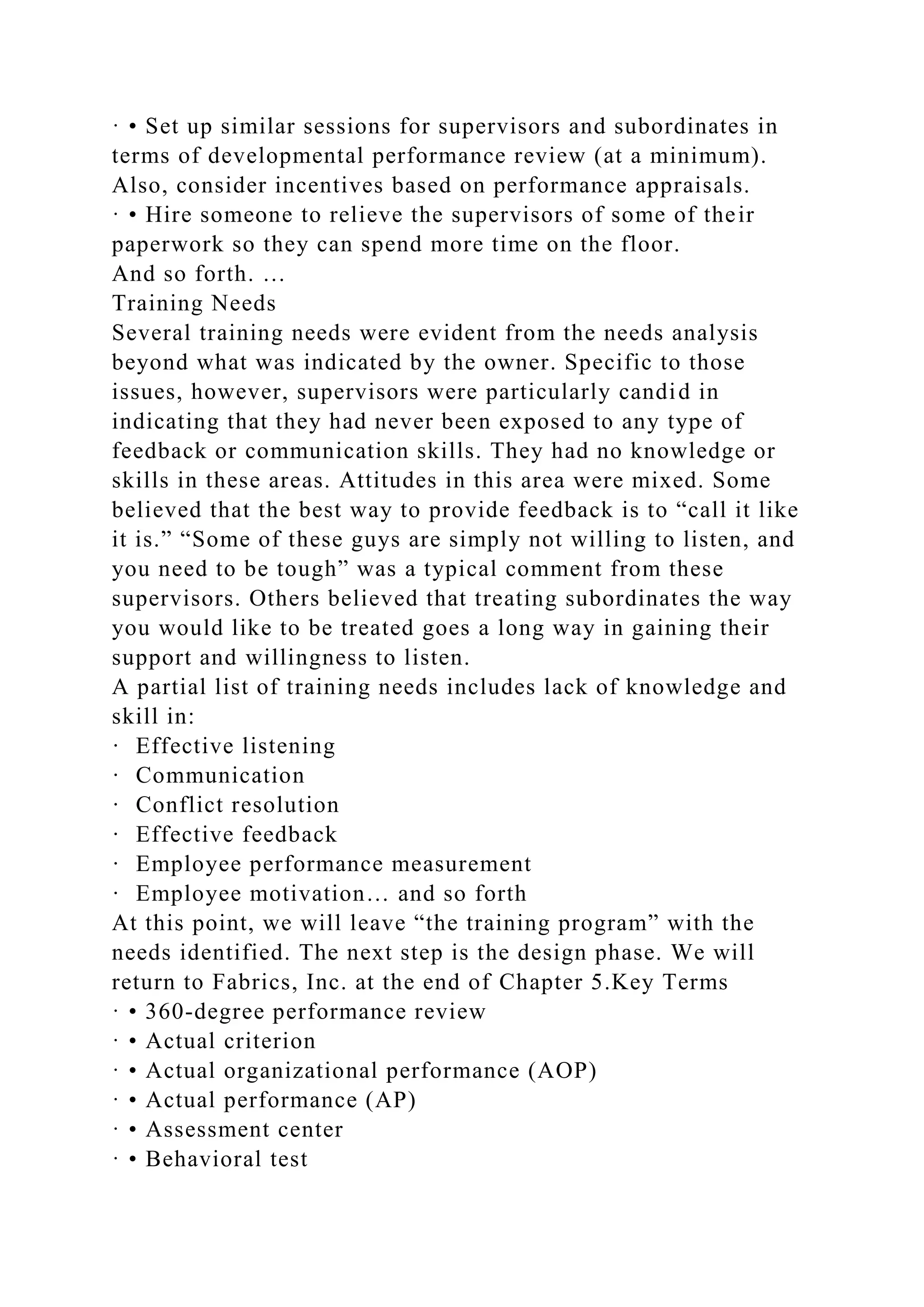

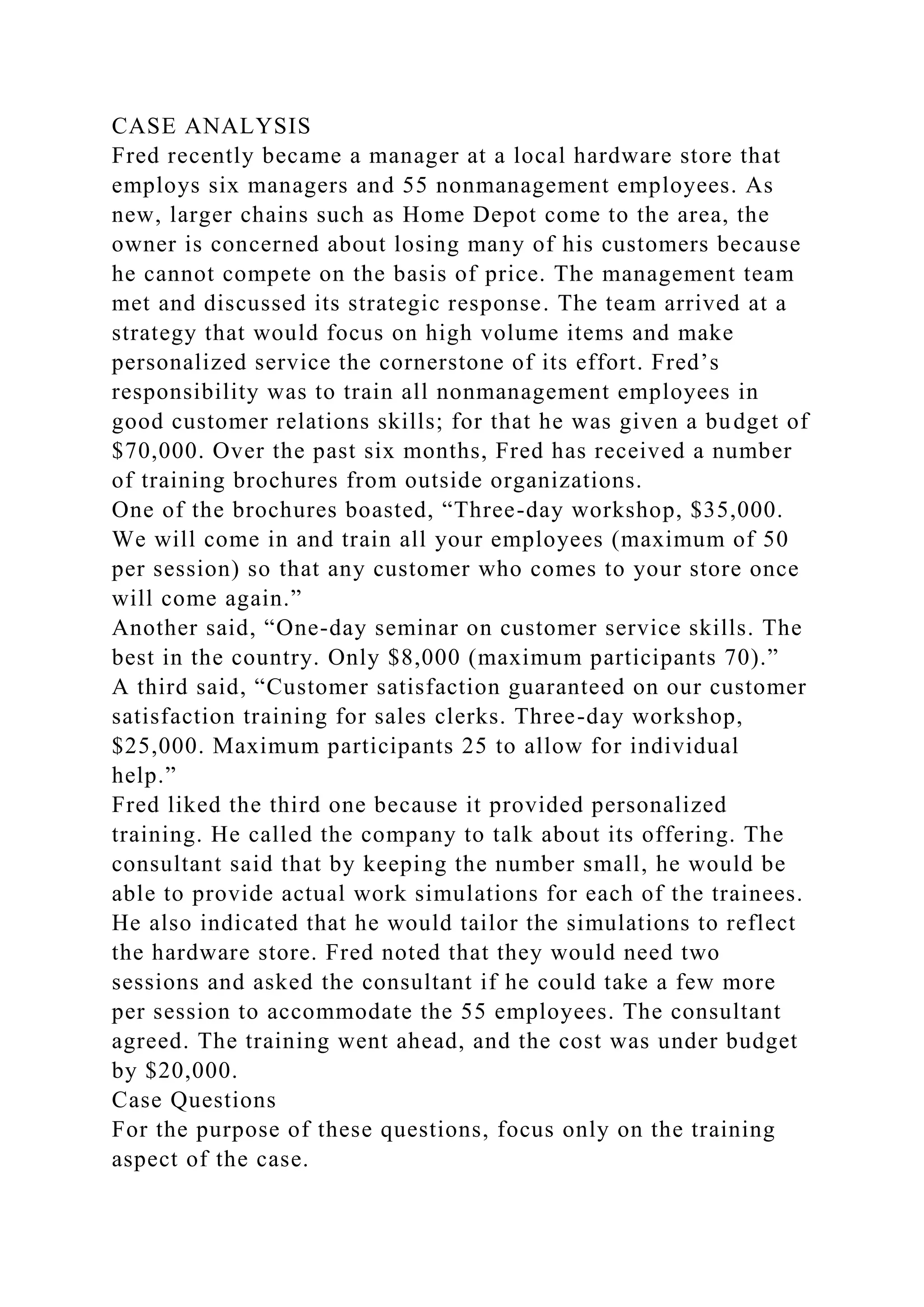

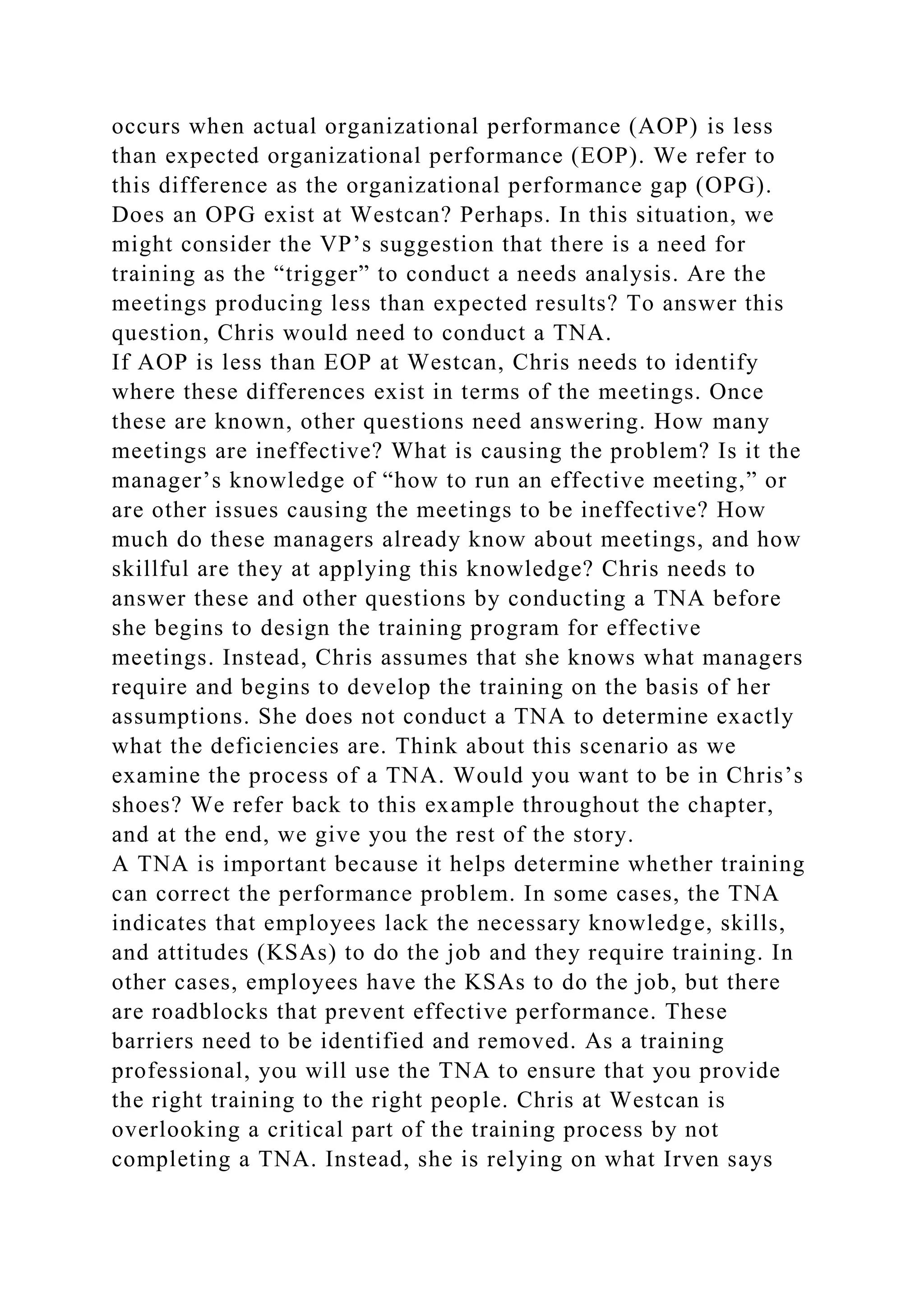

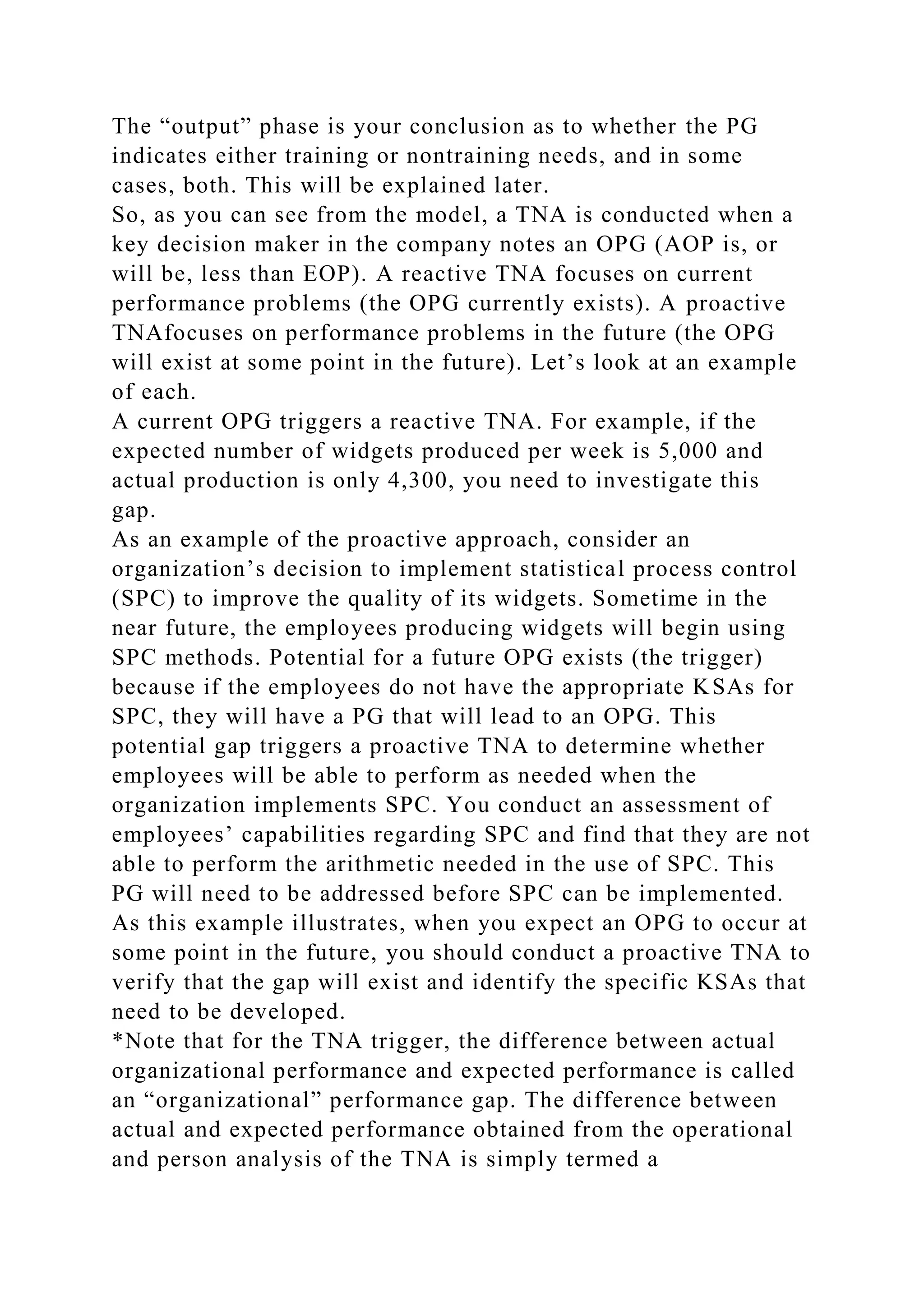

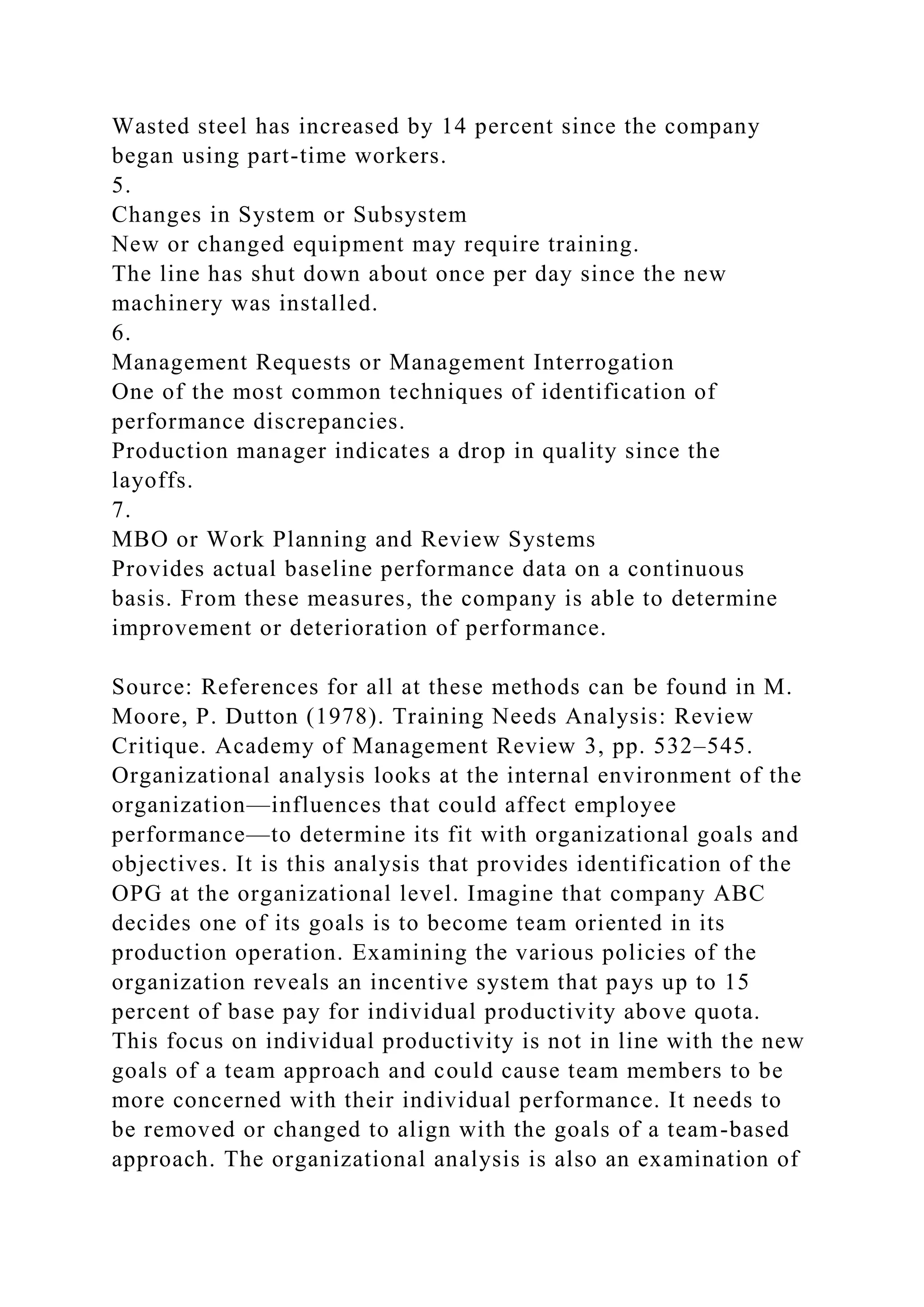

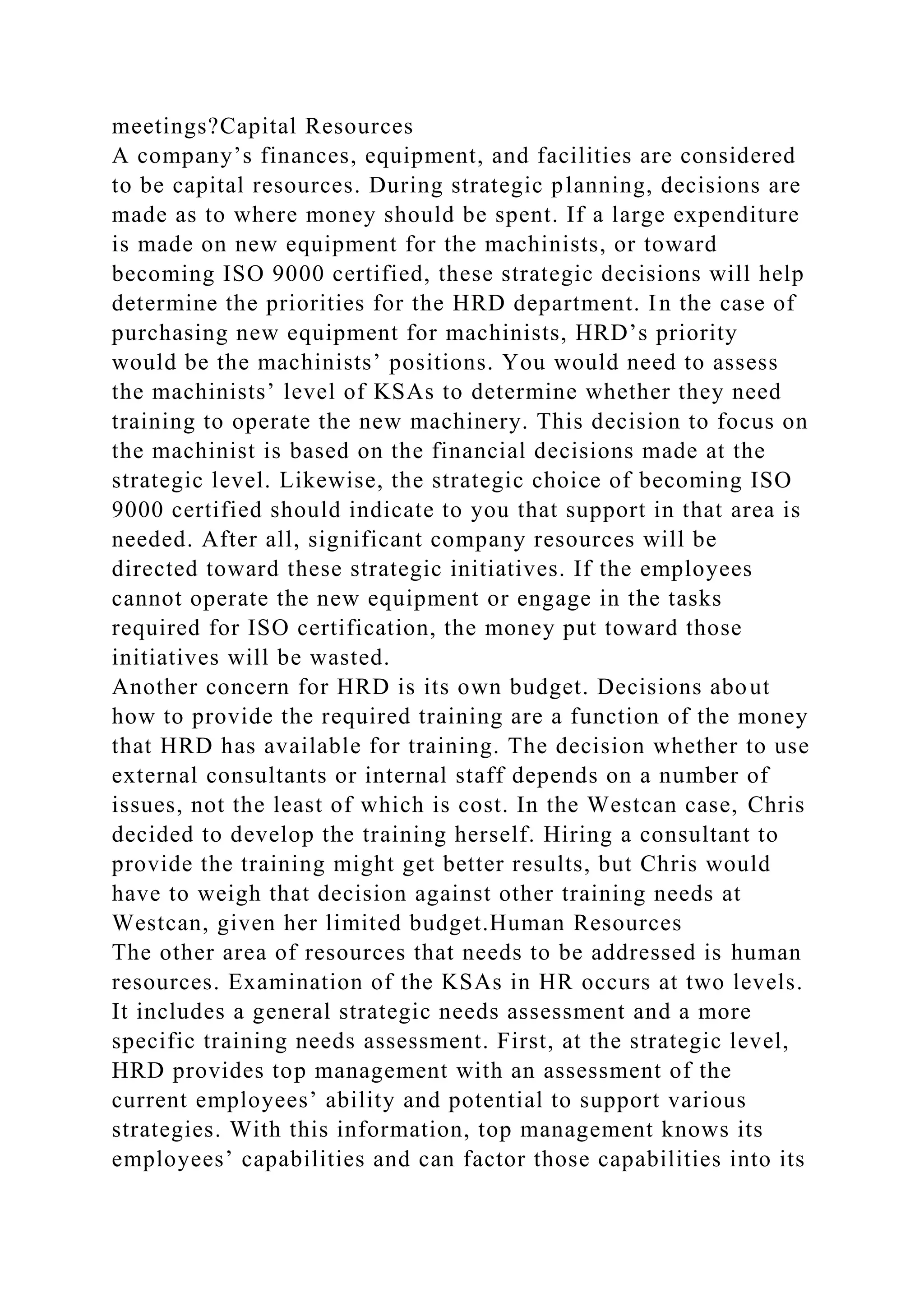

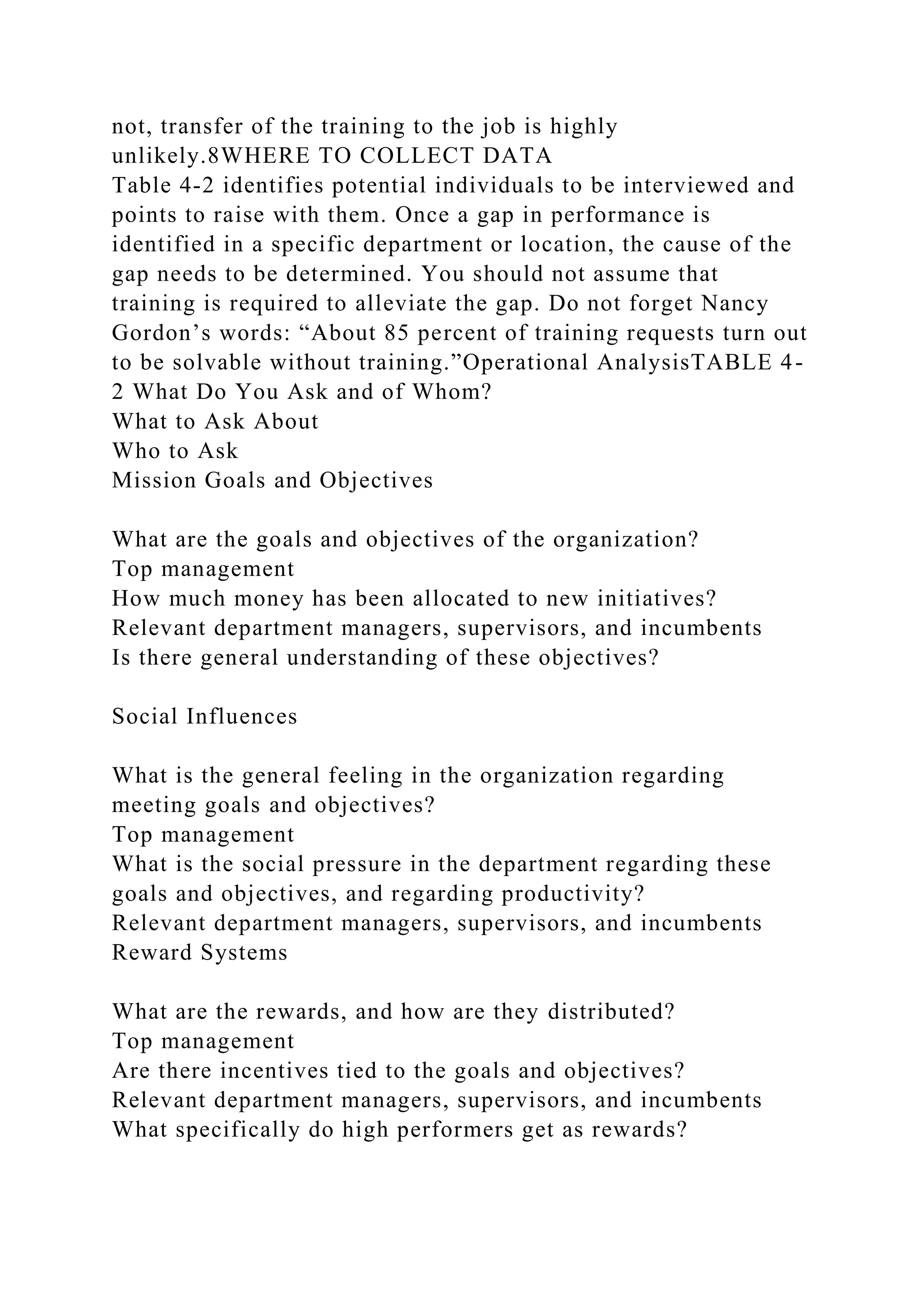

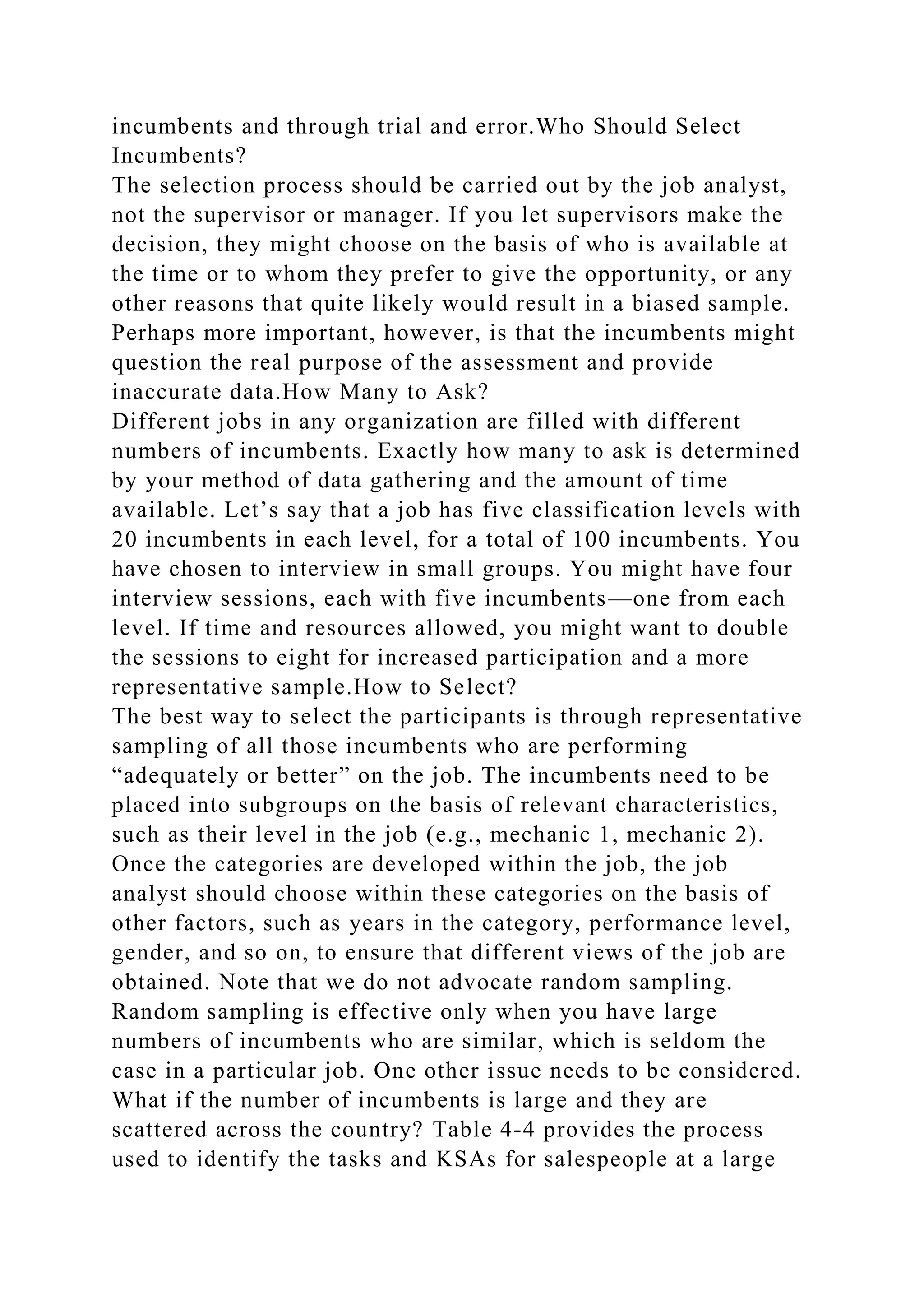

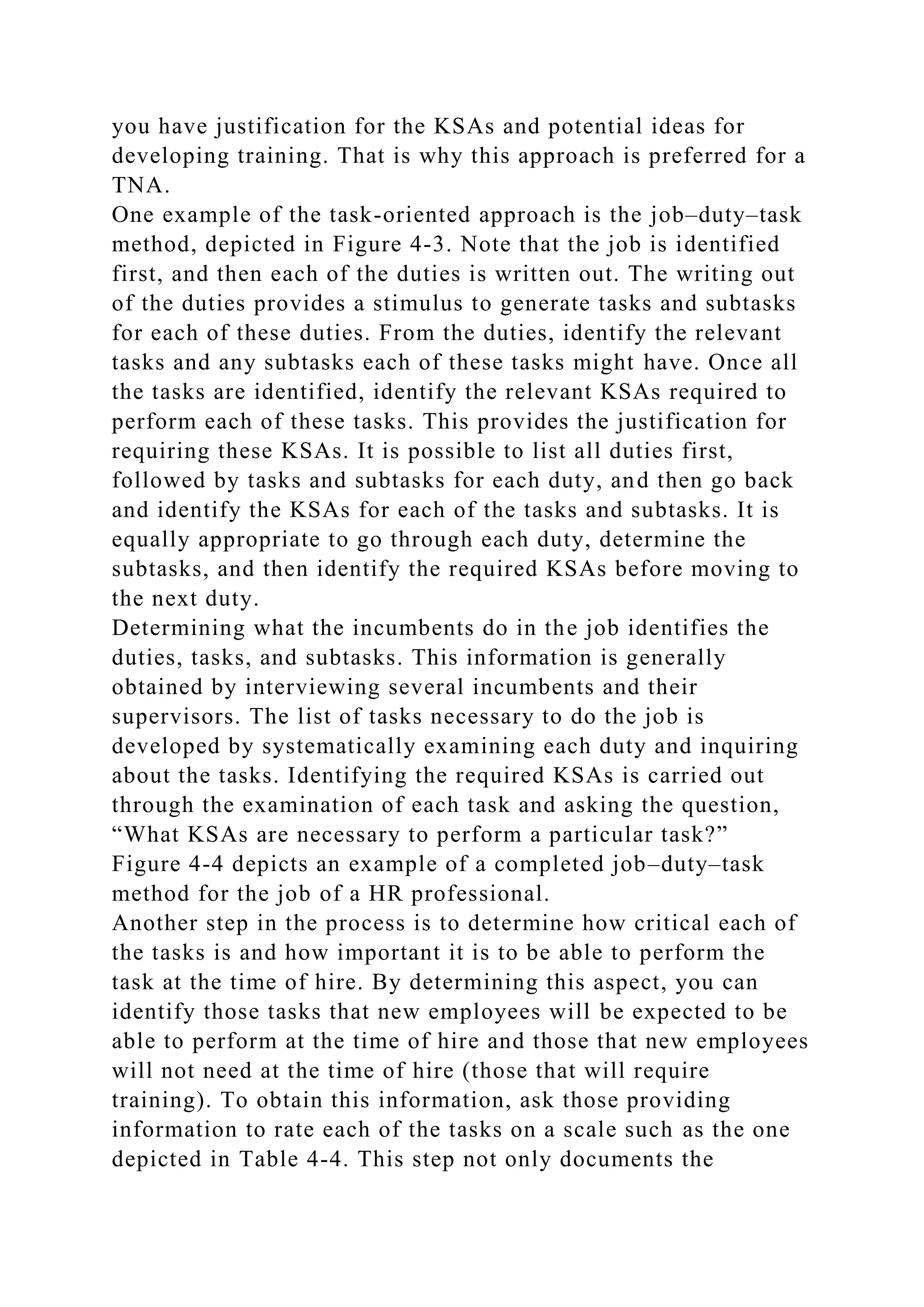

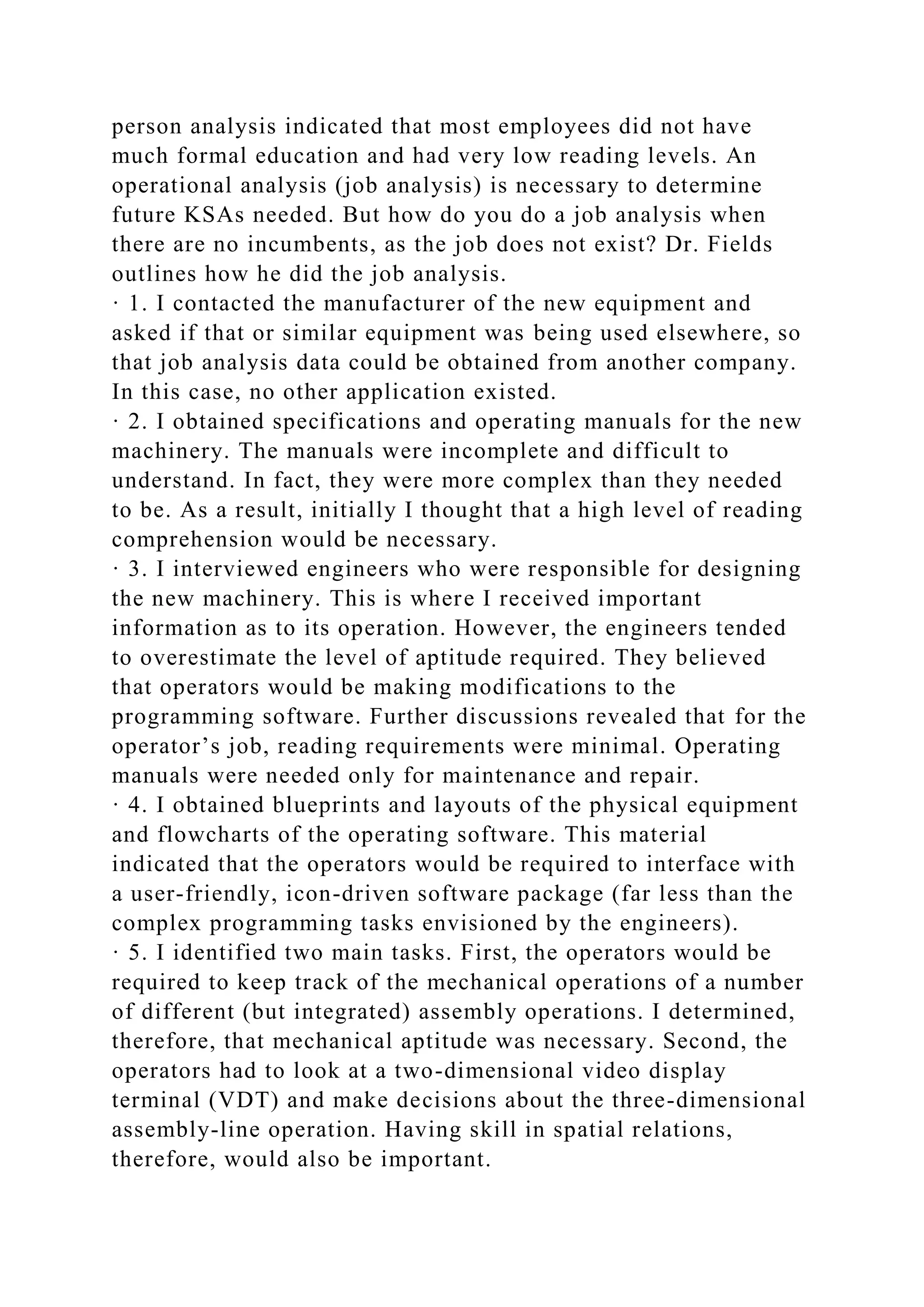

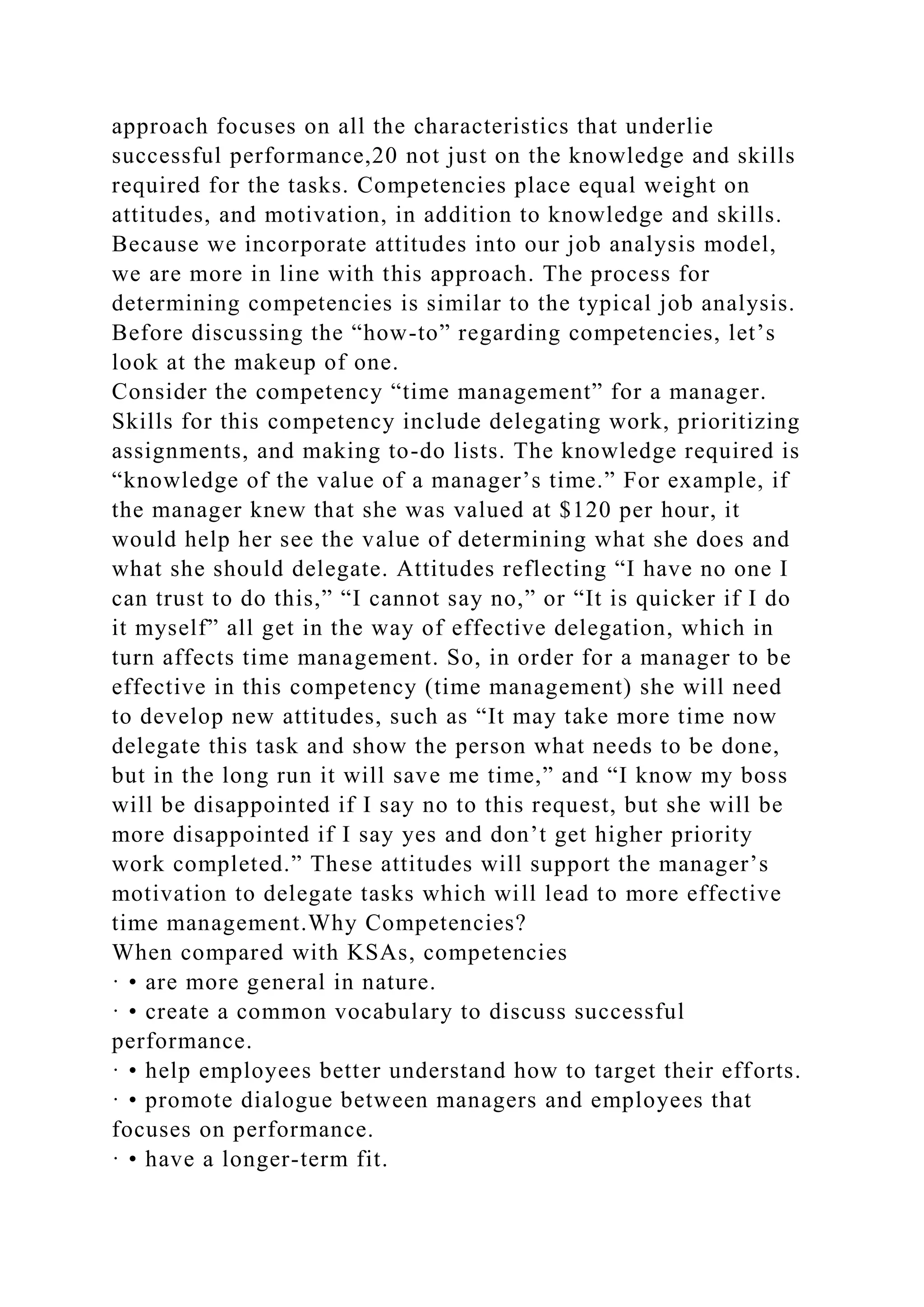

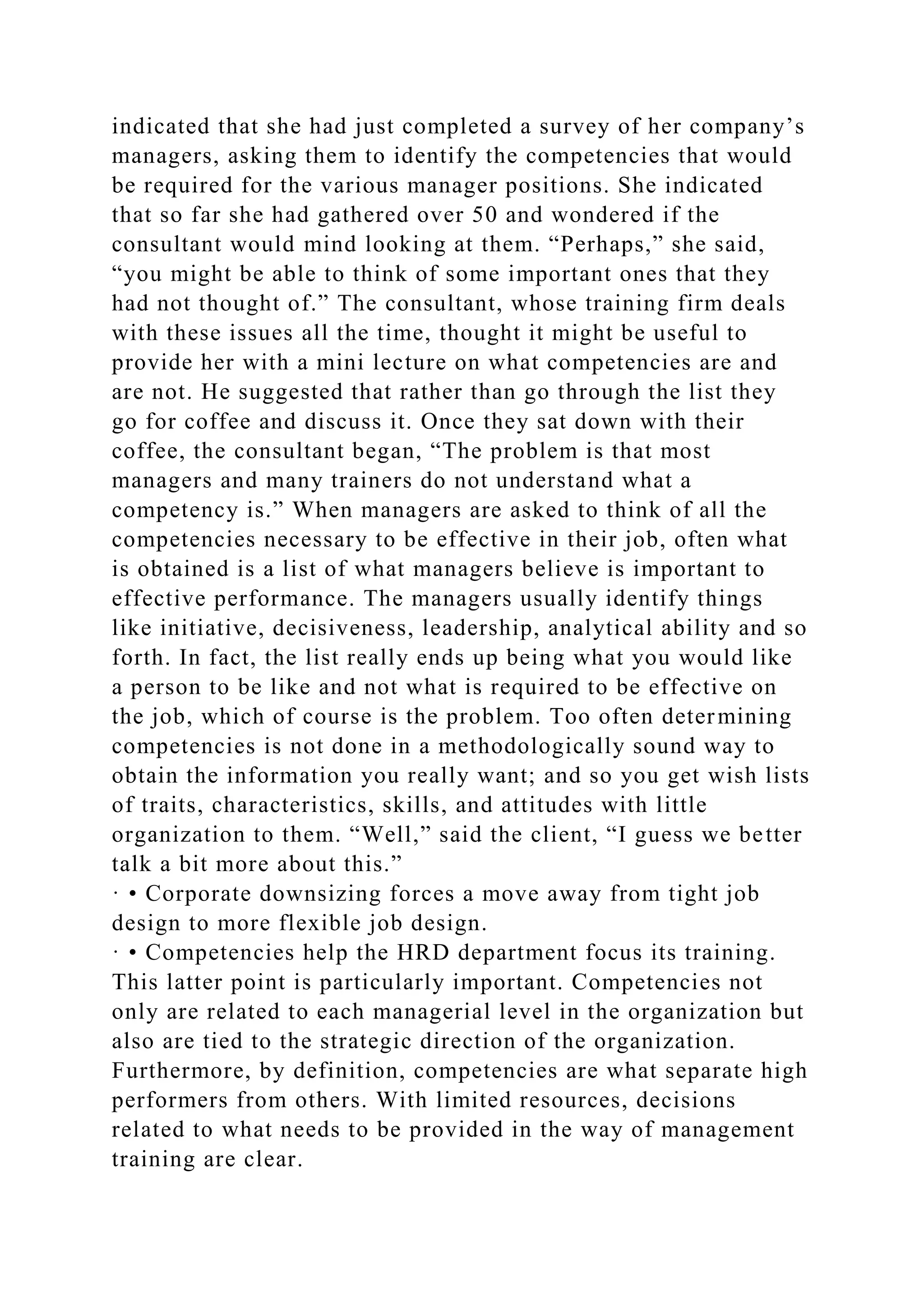

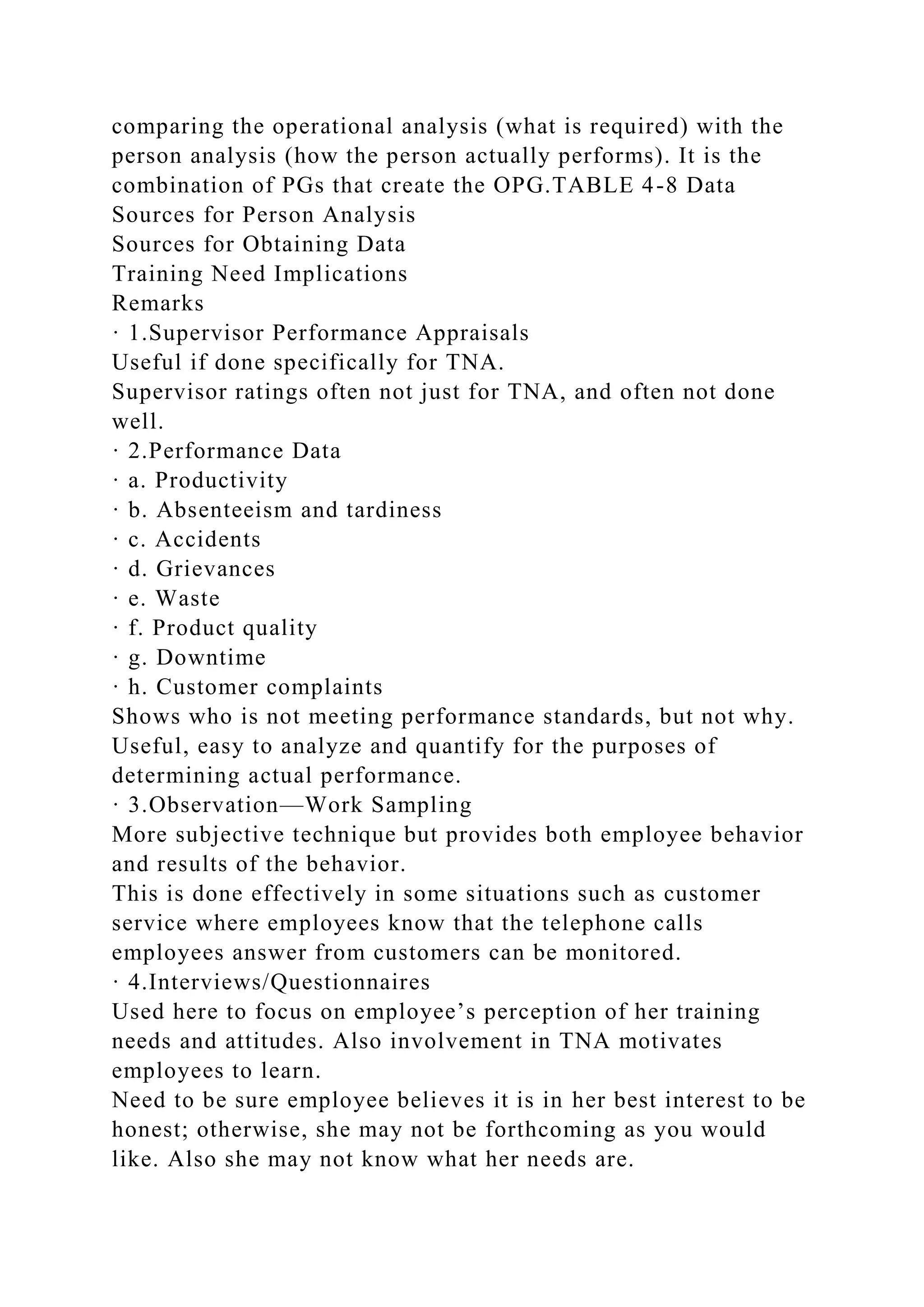

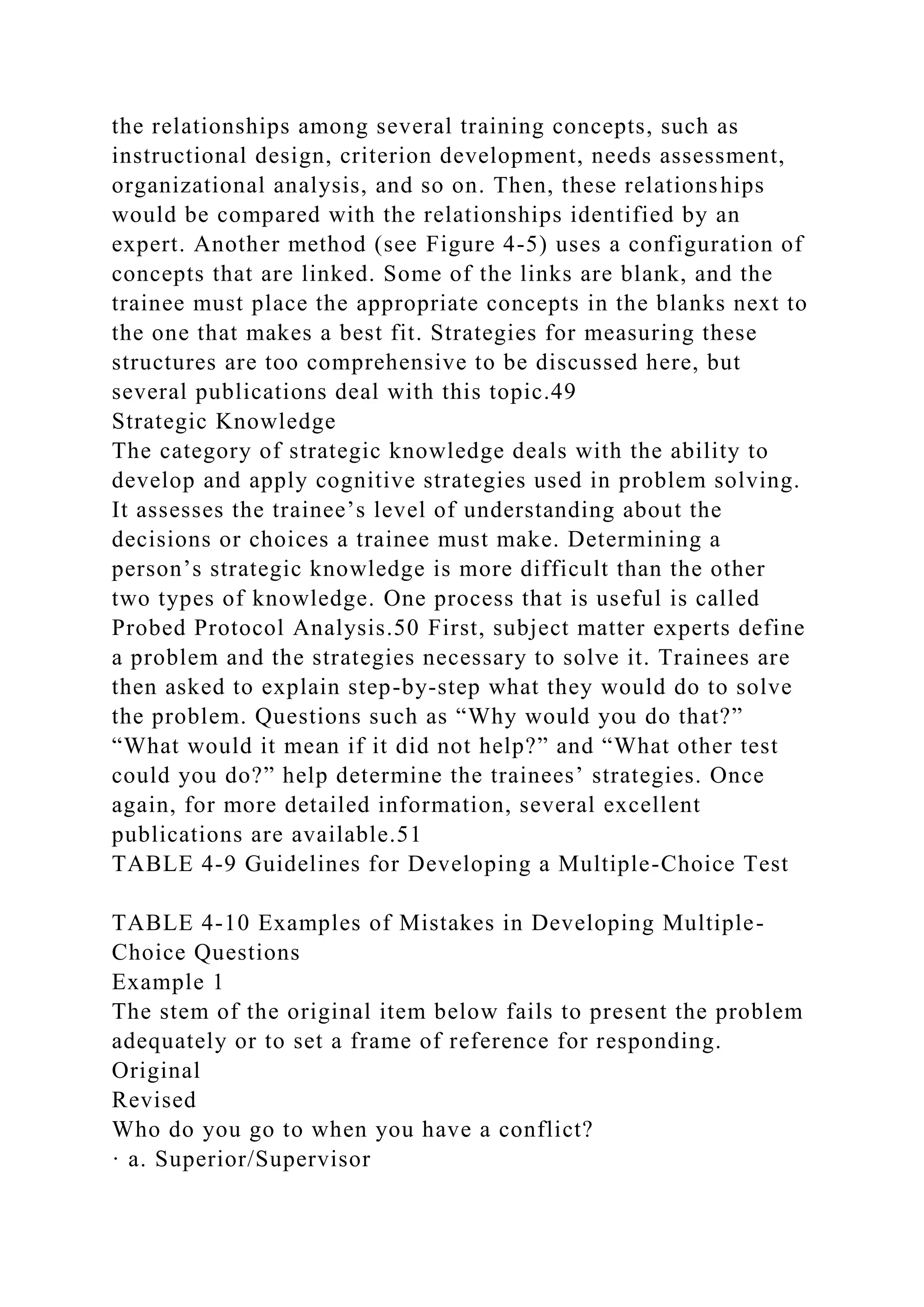

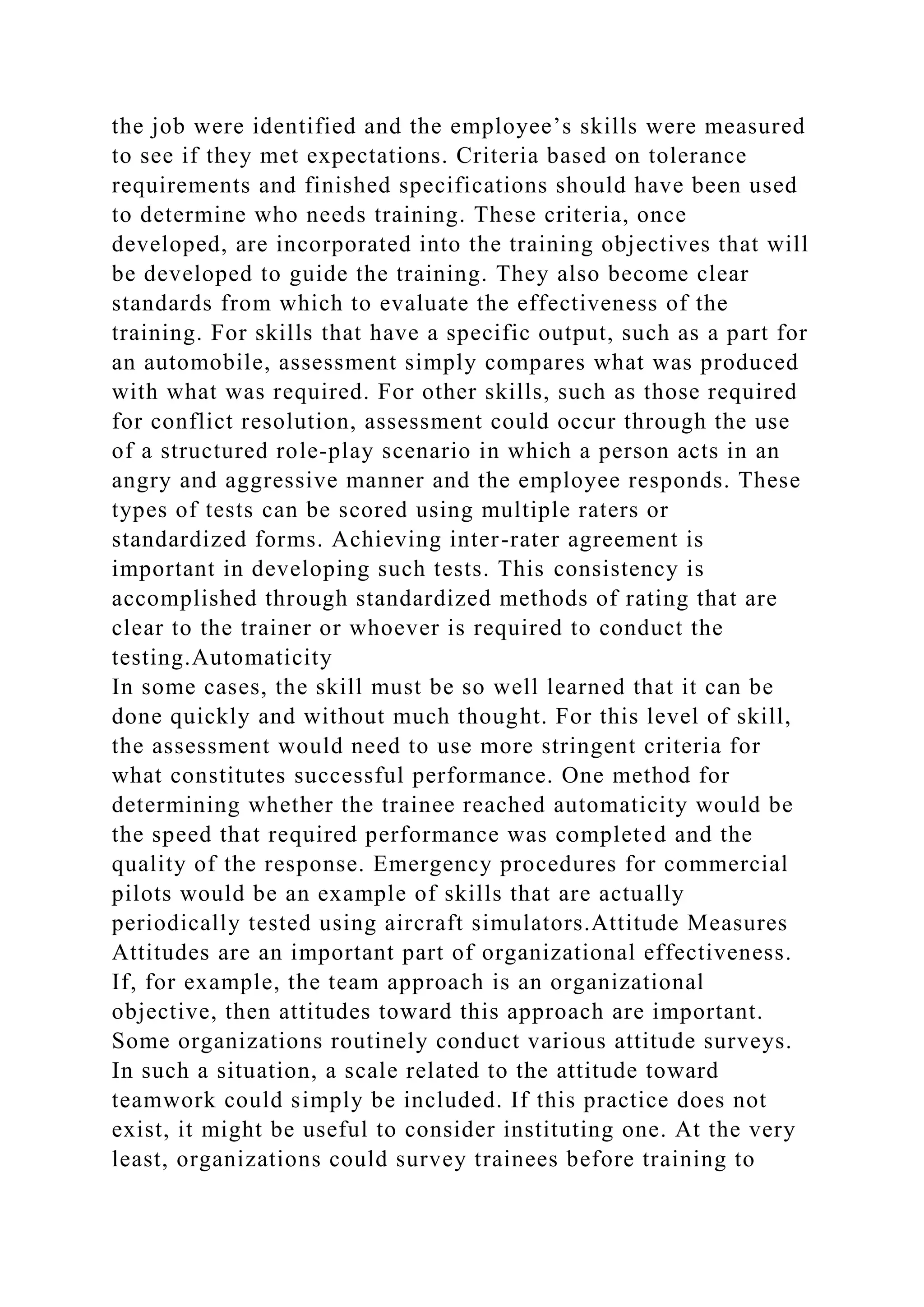

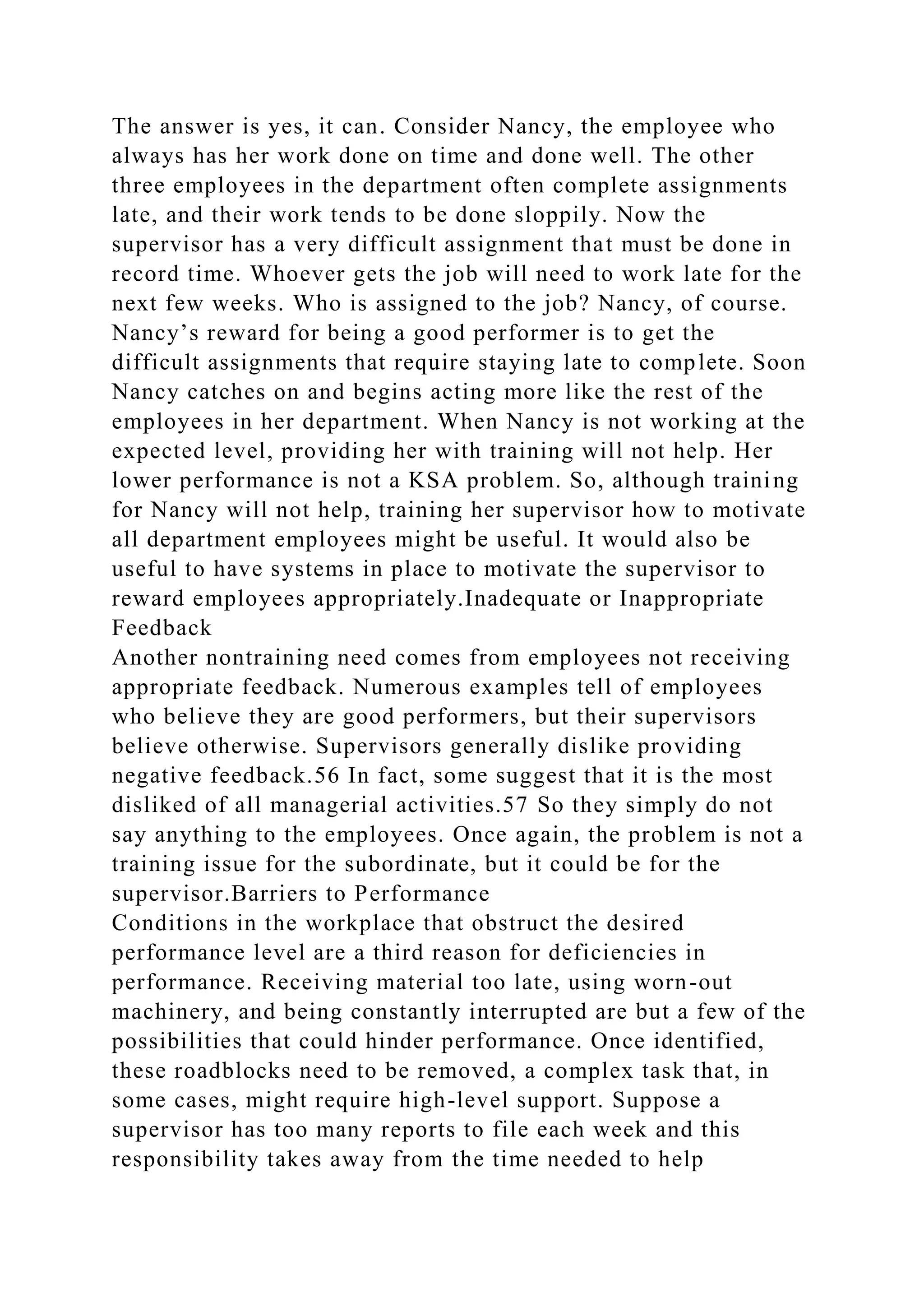

![analysis. This gathering of multiple levels of information at one

time is again illustrated in the Fabrics, Inc. example at the end

of this chapter.

Once the operational analysis data determine the KSAs for the

job, the person analysis will determine whether each of the

relevant employees possesses these KSAs. For those who do

not,

the PG between what is required and what the employee has

serves as the impetus for designing and developing necessary

training.TABLE 4-11 Examples of Attitude Questions

Attitudes toward Empowerment

Please indicate the degree to which you agree or disagree with

the following statements.

1 = Strongly disagree

2 = Disagree

3 = Neither agree nor disagree

4 = Agree

5 = Strongly agree

· 1. Empowering employees is just another way to get more

work done with fewer people. [Reverse scored]

¯1

¯2

¯3

¯4

¯5

· 2. Empowering employees allows everyone to contribute their

ideas for the betterment of the company.

¯1

¯2

¯3

¯4

¯5

· 3. The empowerment program improved my relationship with

my supervisor.

¯1

¯2](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/busi444casestudyinstructionstheanswerstoeachcasestudymu-221031163259-4f26738a/75/BUSI-444Case-Study-InstructionsThe-answers-to-each-Case-Study-mu-docx-61-2048.jpg)

![It is important to understand that in most cases, even if a

training need is identified, nontraining needs are usually also

present. We cannot emphasize enough the importance of these

nontraining factors. Even if training results in the employee

gaining the required competencies, these will not be used on the

job, unless any nontraining causes of the performance gap have

been removed. For training to be successful and transferred to

the job, these “nontraining” factors must be aligned with the

training and the desired employee performance. As Robert

Brinkerhoff, an internationally recognized expert in training

effectiveness said,

· The reality is that these non-training factors are the principle

determinants [for transfer of training], if they are not aligned

and integrated they will easily overwhelm the very best training

[inhibit transfer]. . . . Best estimates are that 80 percent or more

of the eventual impact of training is determined by performance

systems factors [nontraining needs].58 (p. 304)APPROACHES

TO TNA

Now that we have examined the general approach of conducting

a TNA, we examine more closely the distinction between

proactive and reactive approaches.Proactive TNA

The proactive TNA focuses on future HR requirements. From

the unit objectives resulting from the organization’s strategic

planning process, HR must develop unit strategies and tactics

(see Figure 2-1 on page 28) to ensure that the organization has

employees with the required KSAs in all of its critical jobs.

Two approaches can be taken to develop the needed KSAs:

· 1. Prepare employees for promotions or transfers to different

jobs.

· 2. Prepare employees for changes in their current jobs.

An effective, proactive procedure used for planning key

promotions and transfers is succession planning. Succession

planning is the identification and development of employees

perceived to be of high potential so they can fill key positions

in the company as they become vacant. The first step in the

development of a succession plan is to identify key positions in](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/busi444casestudyinstructionstheanswerstoeachcasestudymu-221031163259-4f26738a/75/BUSI-444Case-Study-InstructionsThe-answers-to-each-Case-Study-mu-docx-68-2048.jpg)