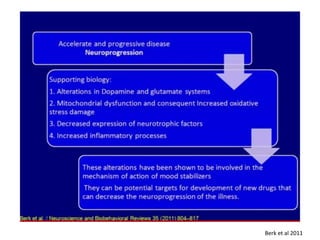

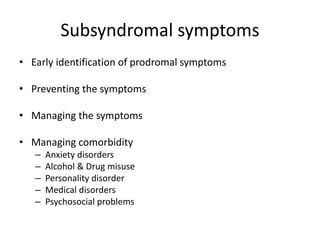

This document provides an overview of bipolar disorder from multiple perspectives including the brain, cognition, circadian rhythms, life events, and dysfunctional beliefs. Key points include:

1) Brain imaging and studies show differences in brain structures and activity in areas related to mood regulation like the prefrontal cortex and limbic system between those with bipolar disorder and healthy controls.

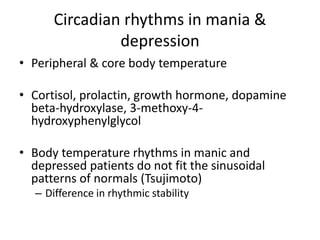

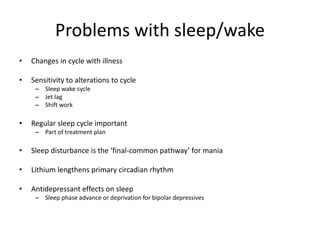

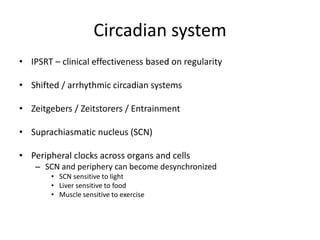

2) Disruptions to circadian rhythms and sleep patterns are implicated in bipolar disorder through their effects on mood regulation.

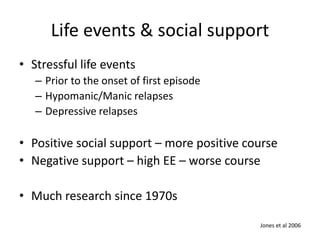

3) Stressful life events and lack of social support are associated with increased risk of bipolar episodes, while positive social support predicts a better illness course.

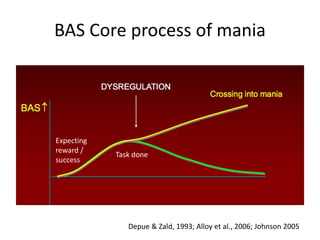

4) Cognitive models suggest dysfunctional beliefs and information processing styles may