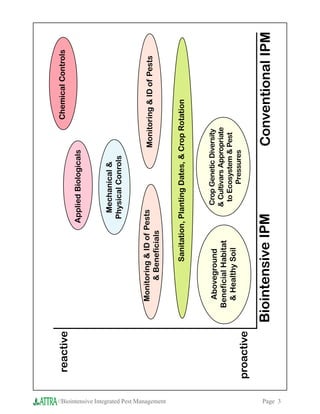

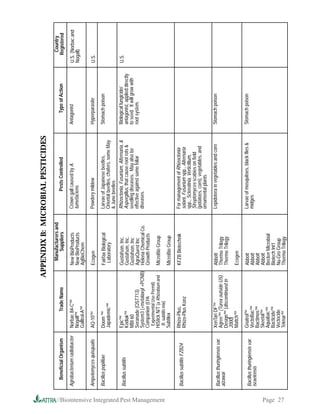

This document provides an overview of biointensive integrated pest management (IPM). It discusses how conventional IPM has focused on pesticides as the primary tool, whereas biointensive IPM takes a more ecological approach by designing agricultural systems to enhance natural pest controls and only using pesticides as a last resort. The document outlines various proactive cultural, biological, and mechanical controls that can be used in biointensive IPM, as well as strategies for monitoring pests and determining economic thresholds for action. It also discusses considerations for record keeping and using IPM certification and marketing.