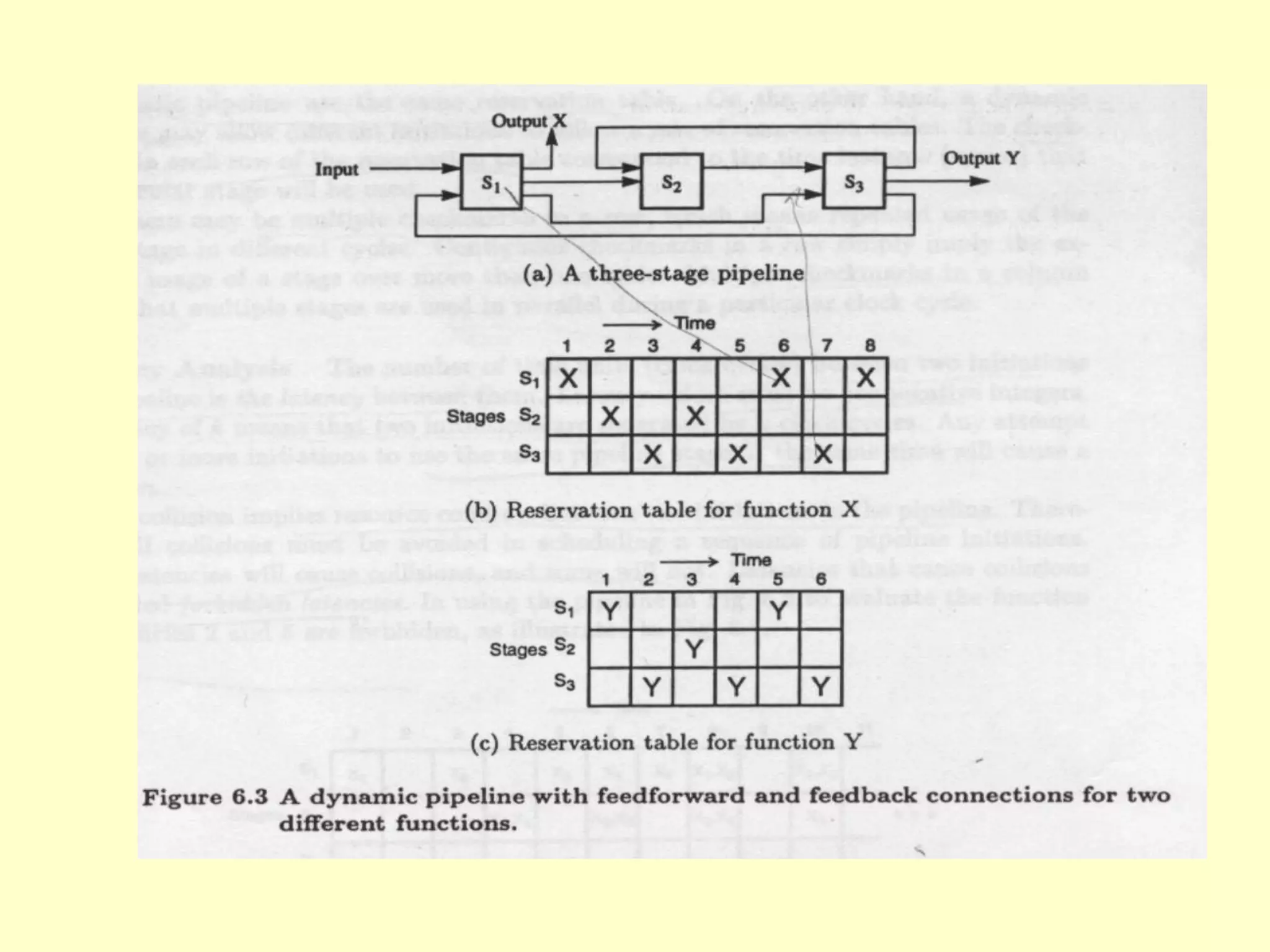

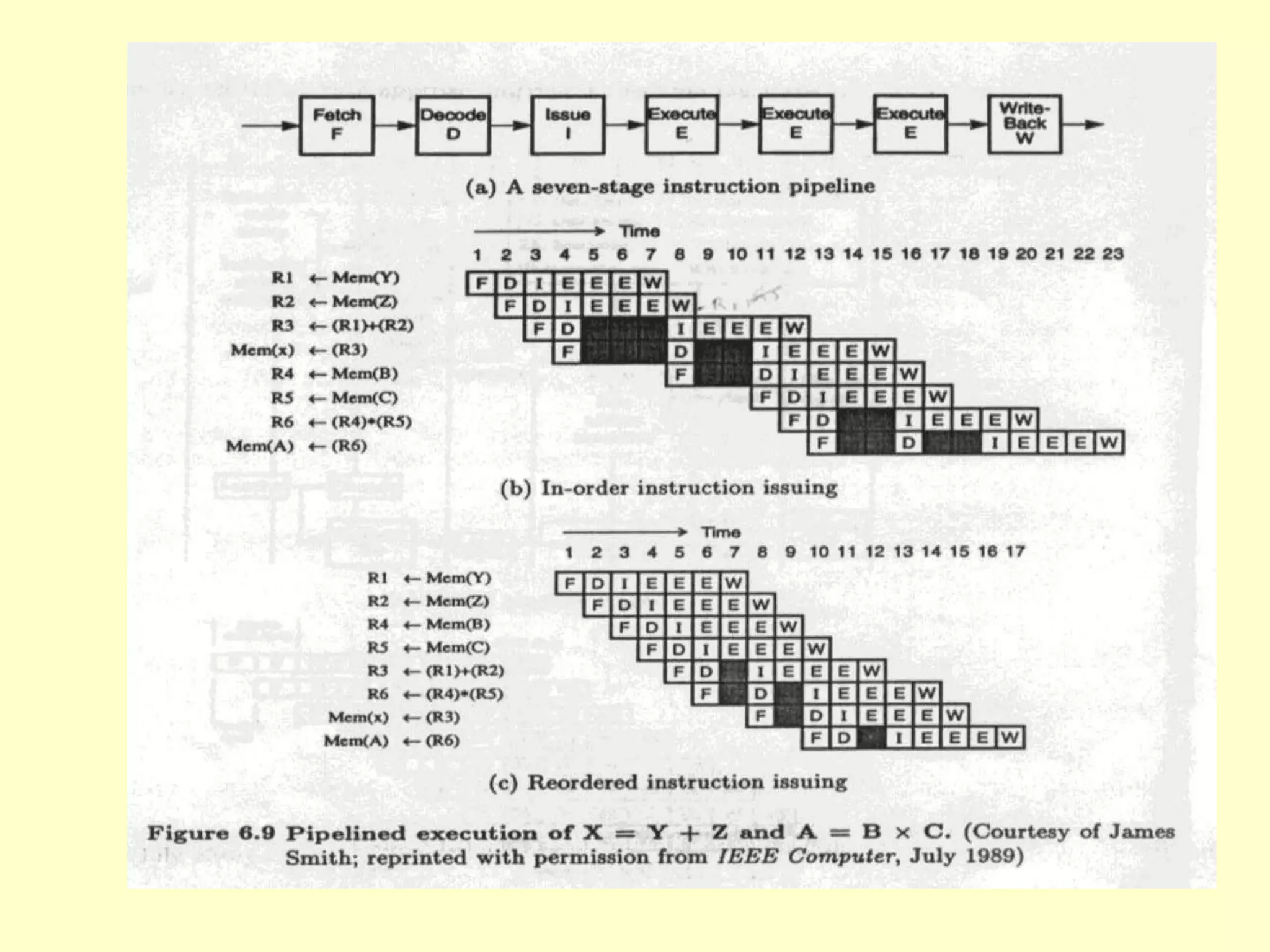

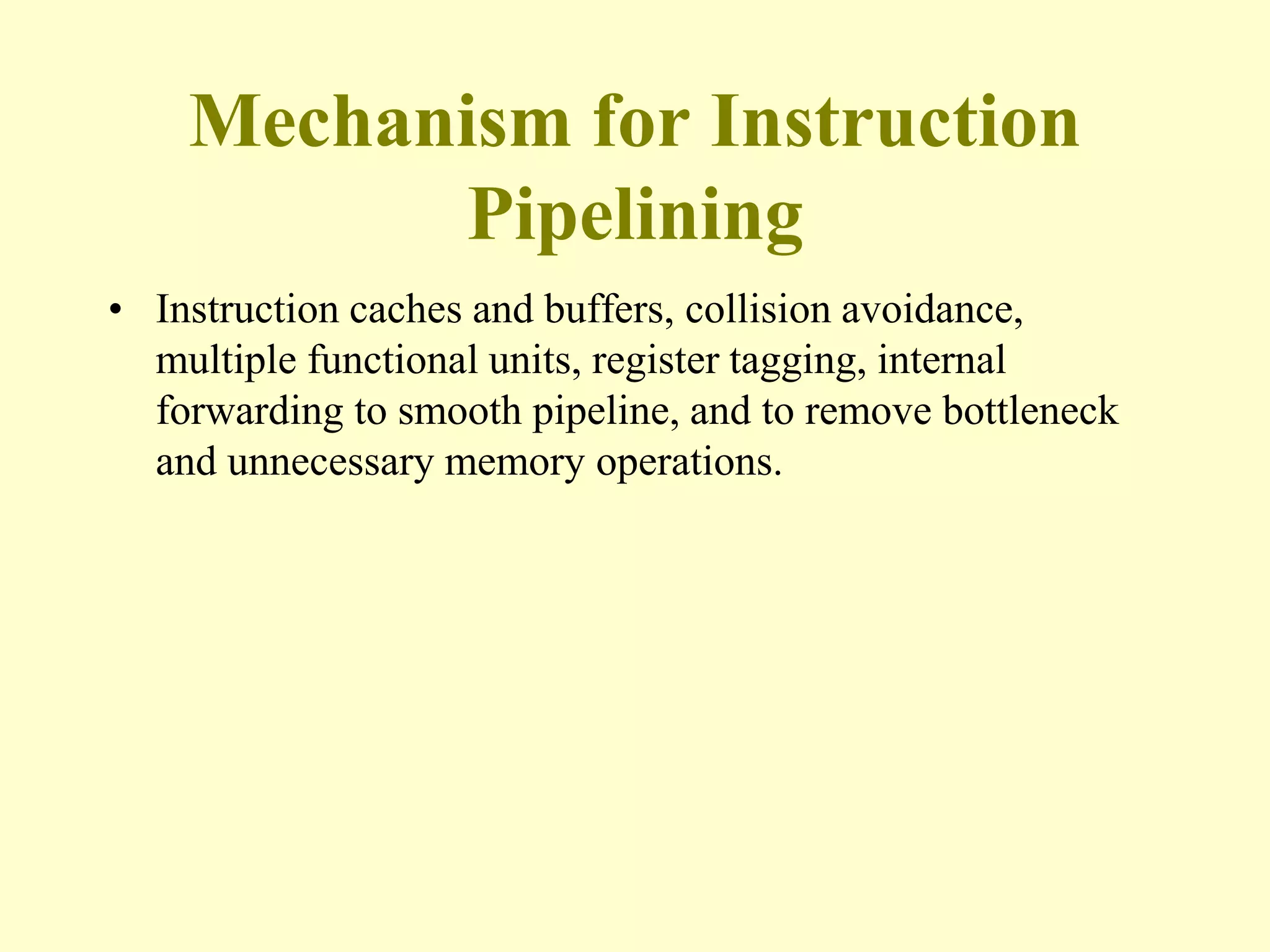

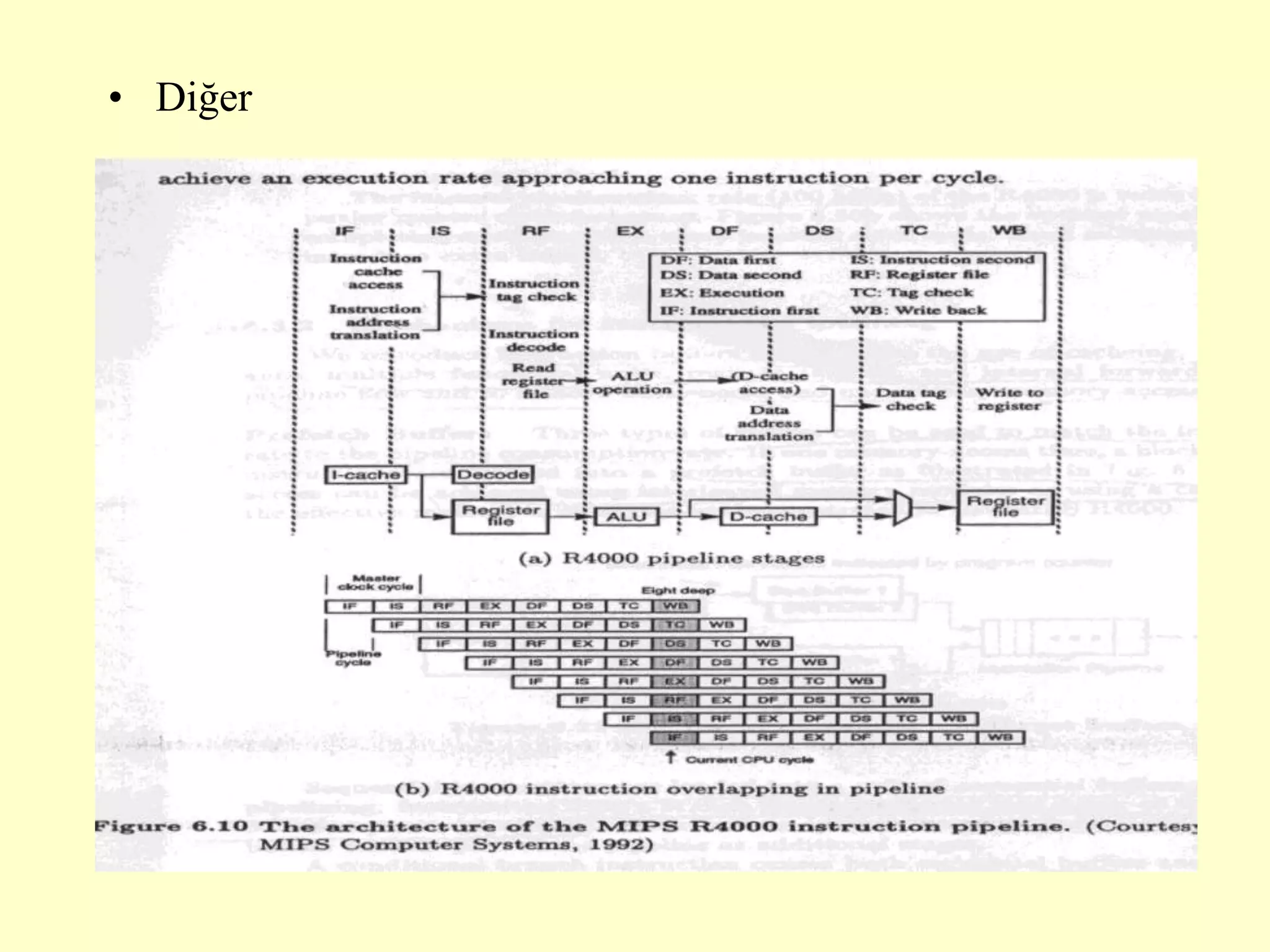

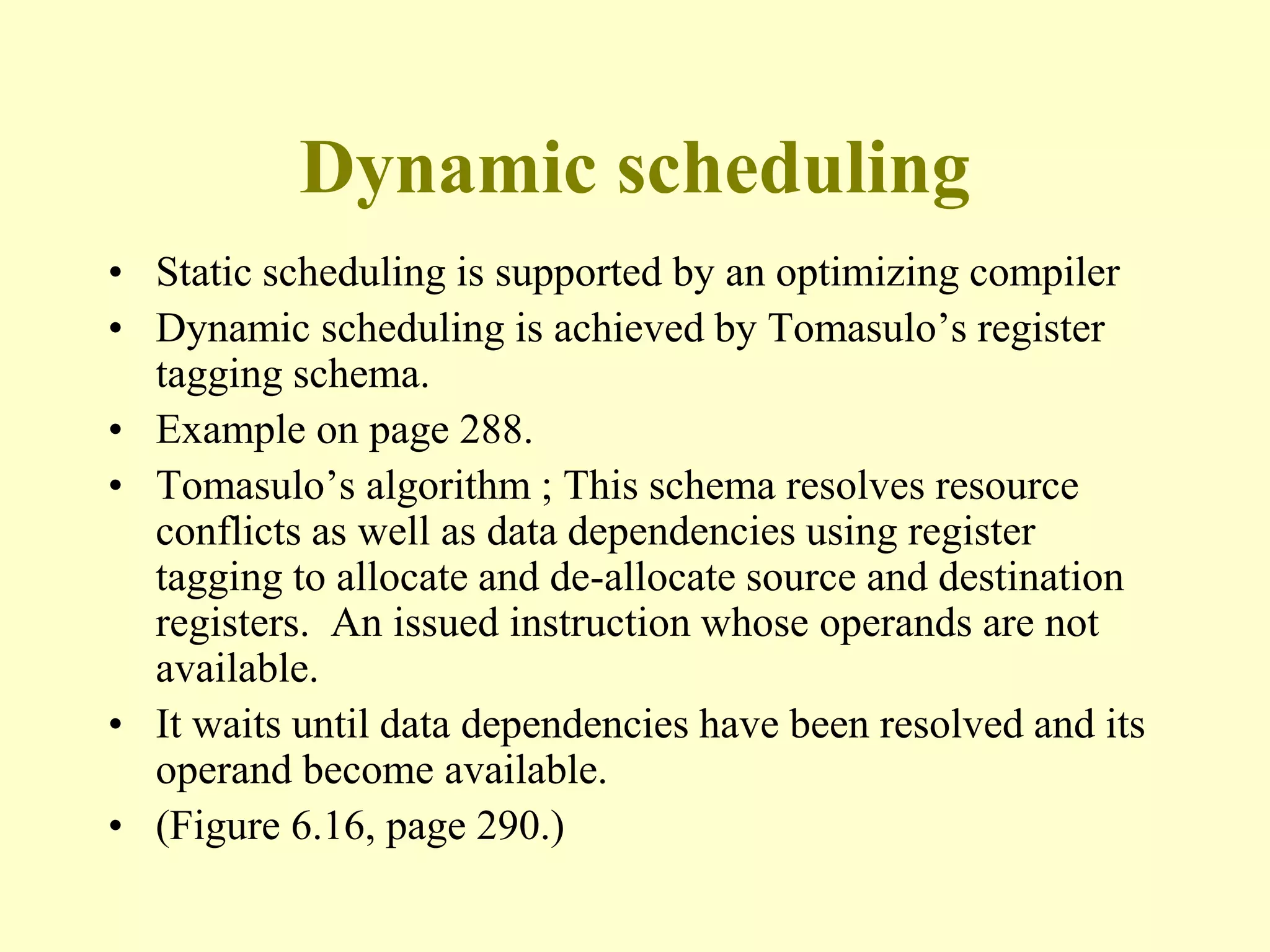

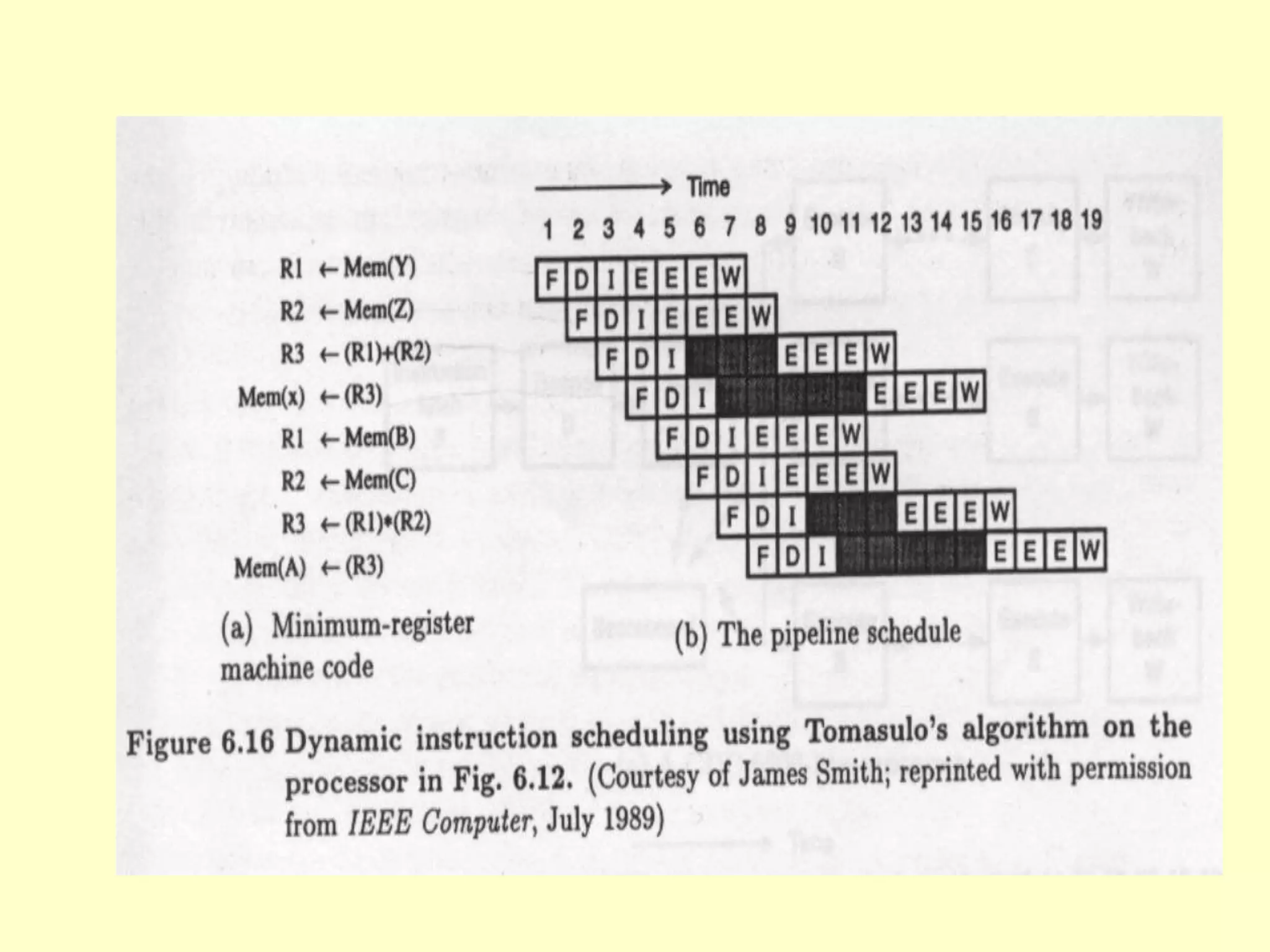

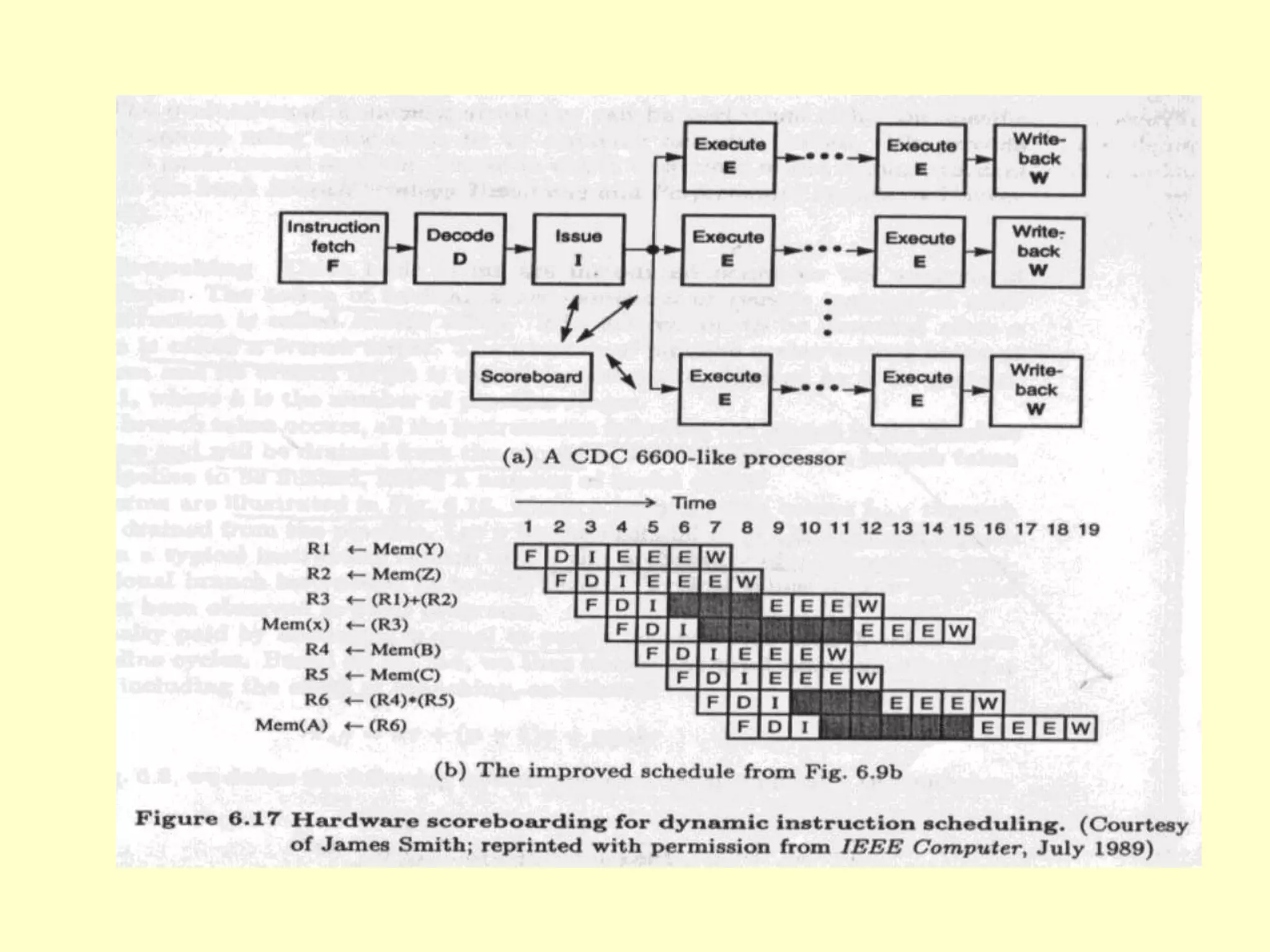

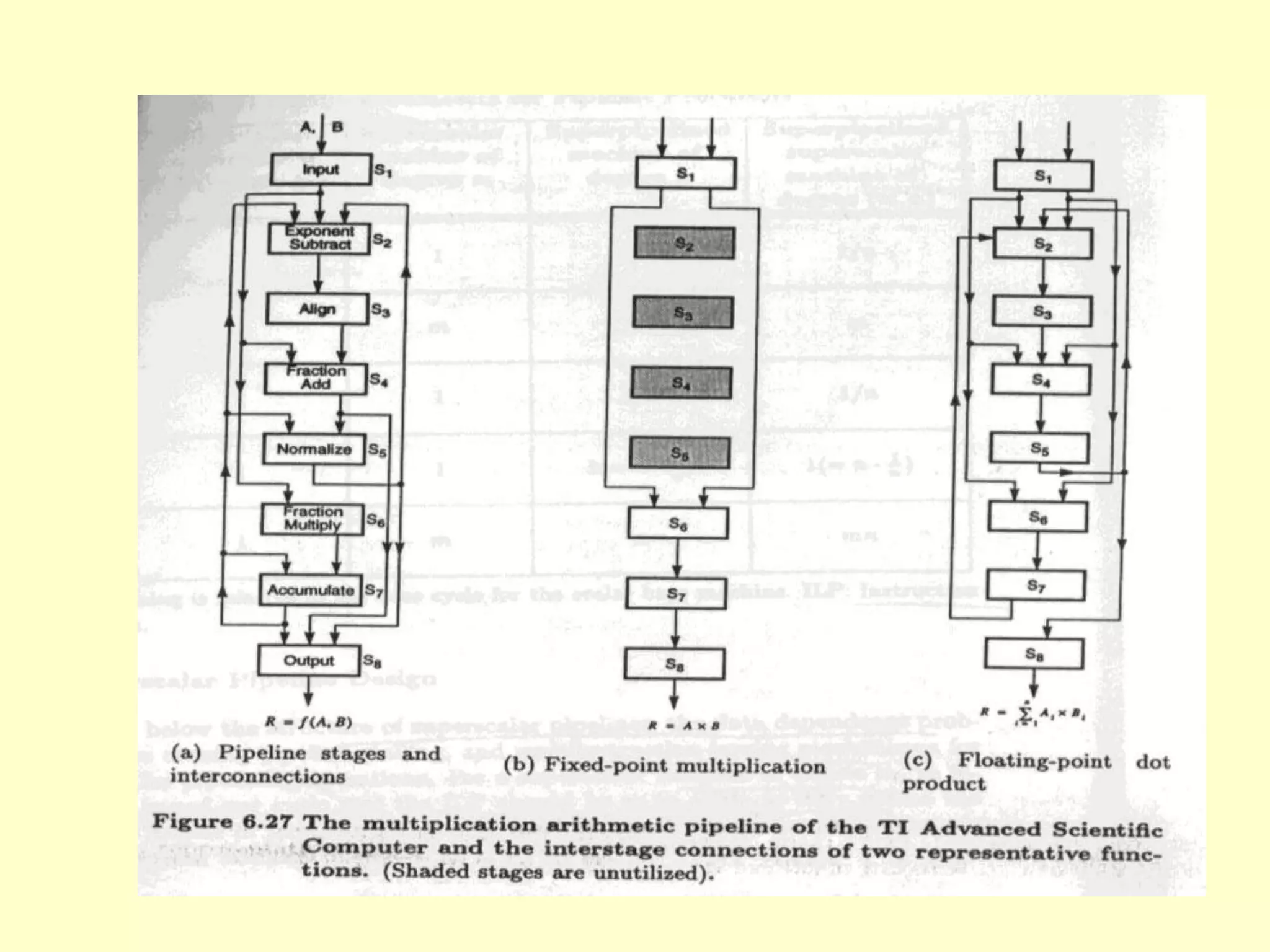

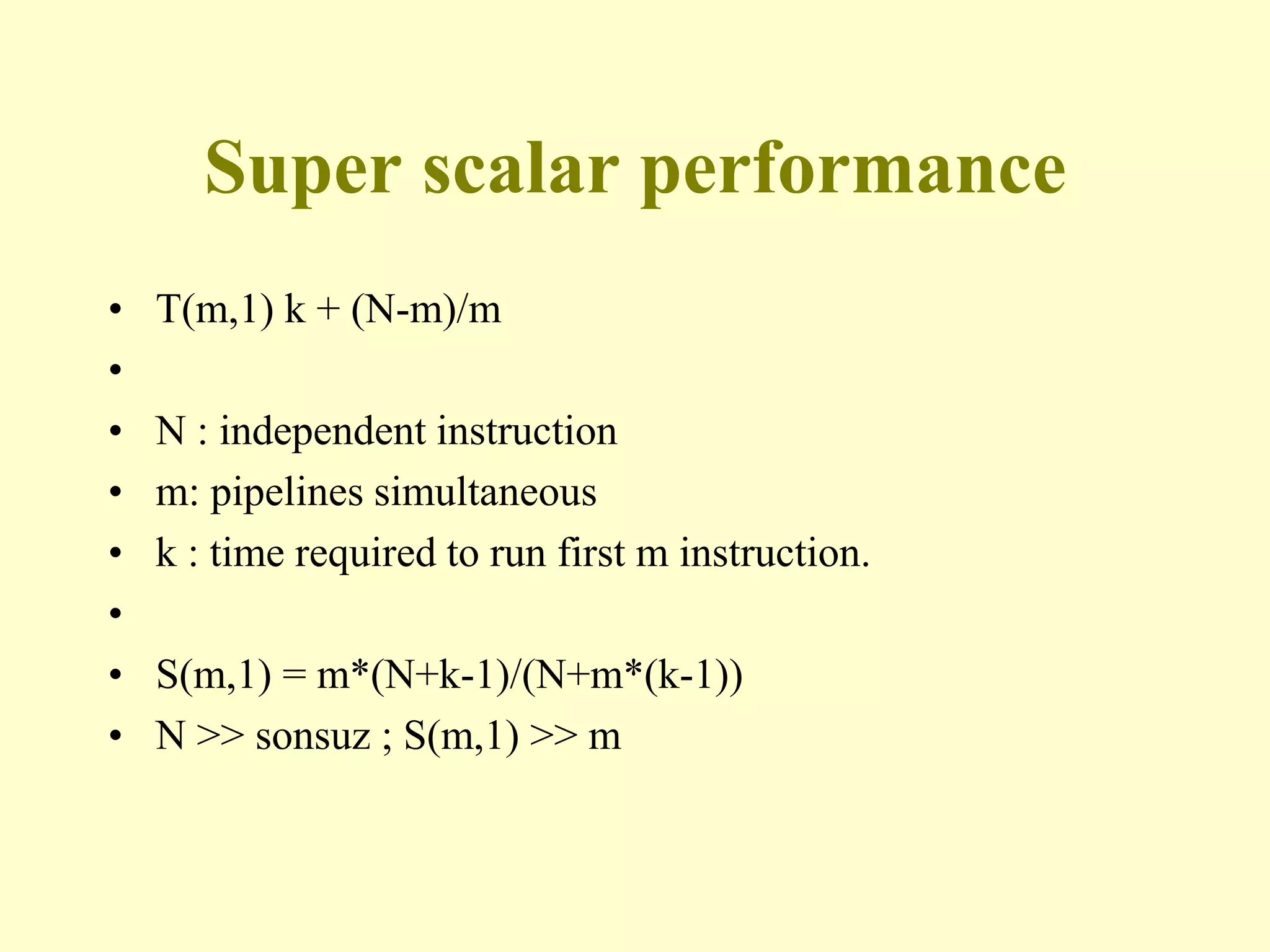

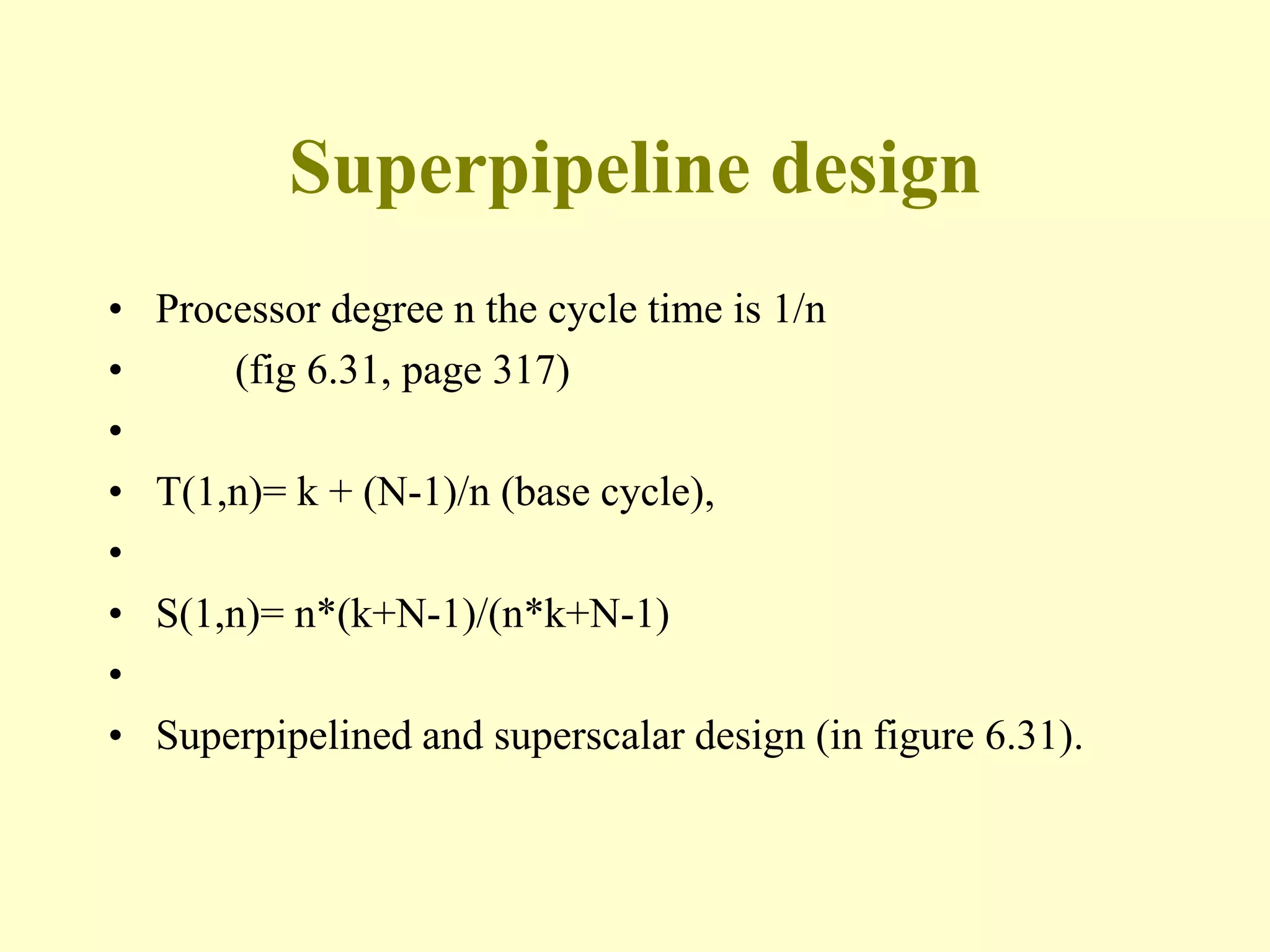

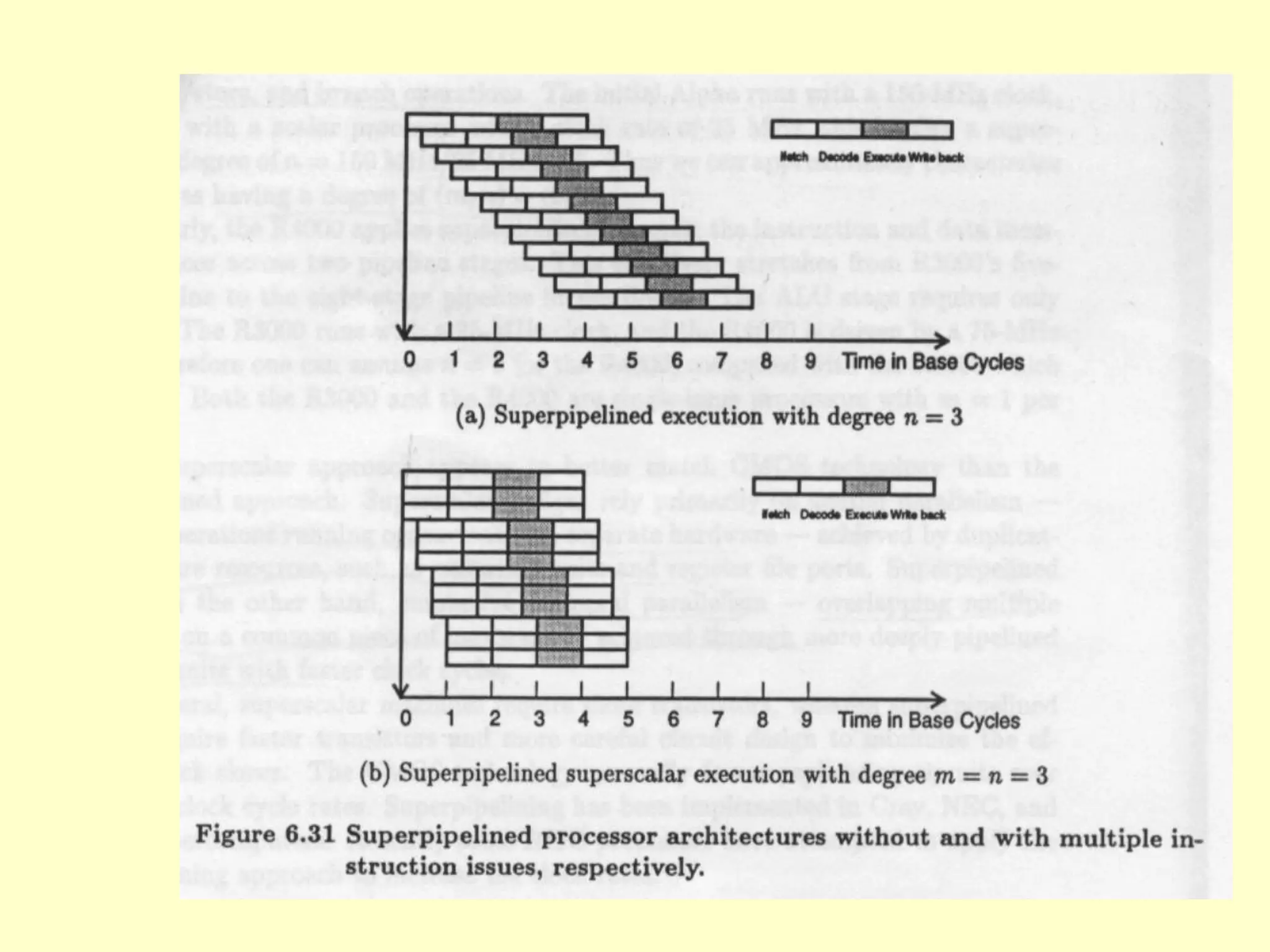

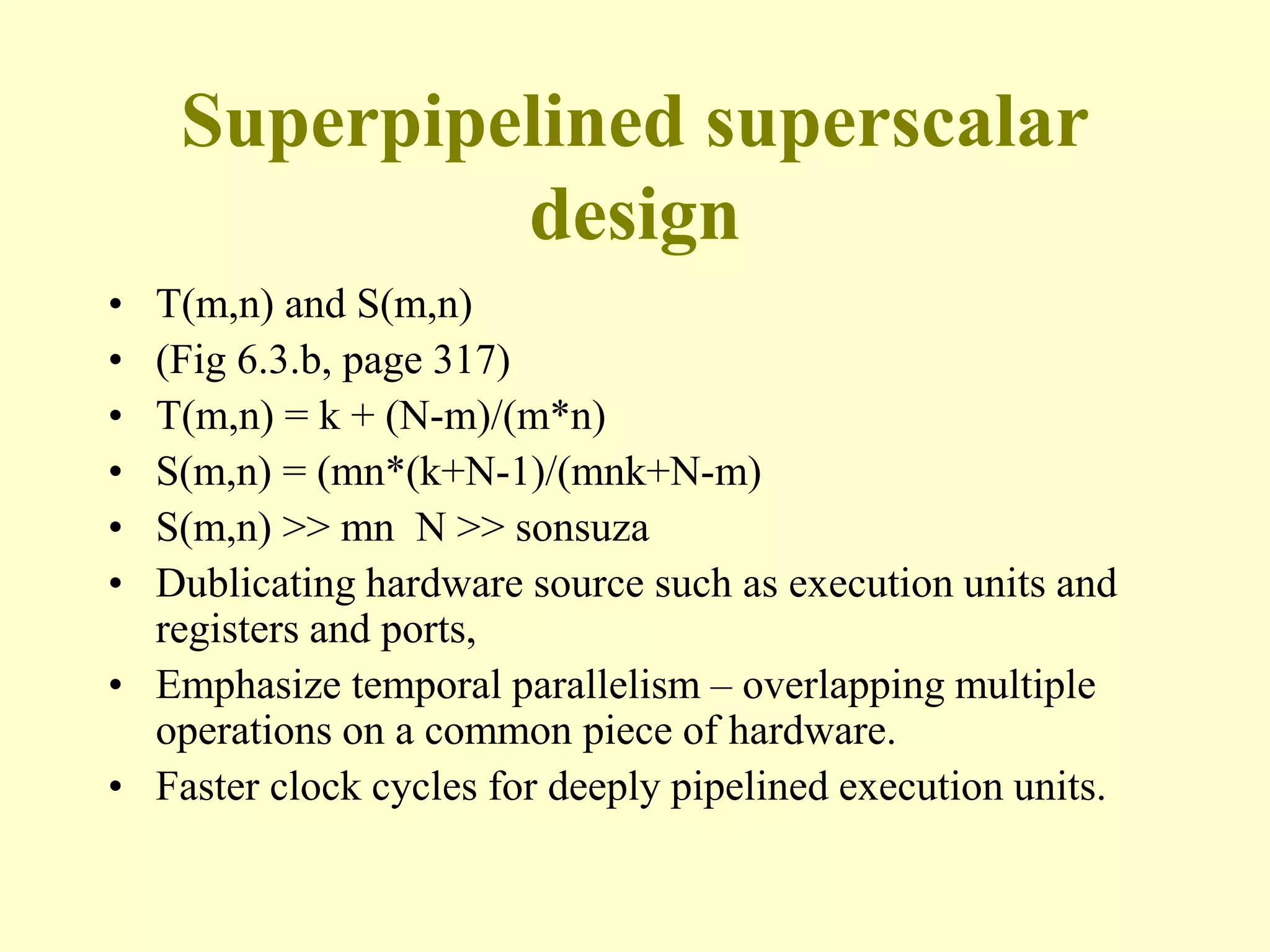

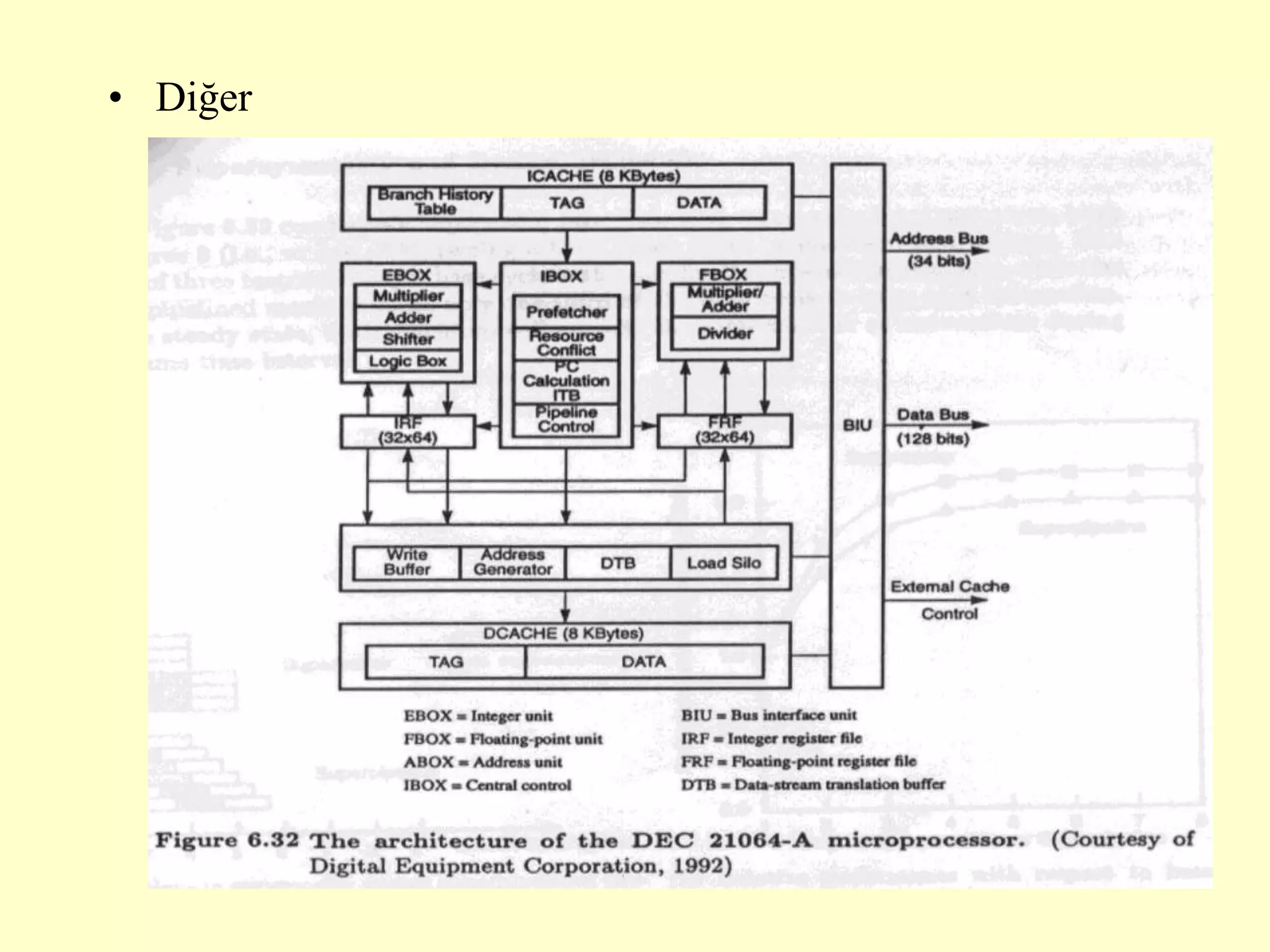

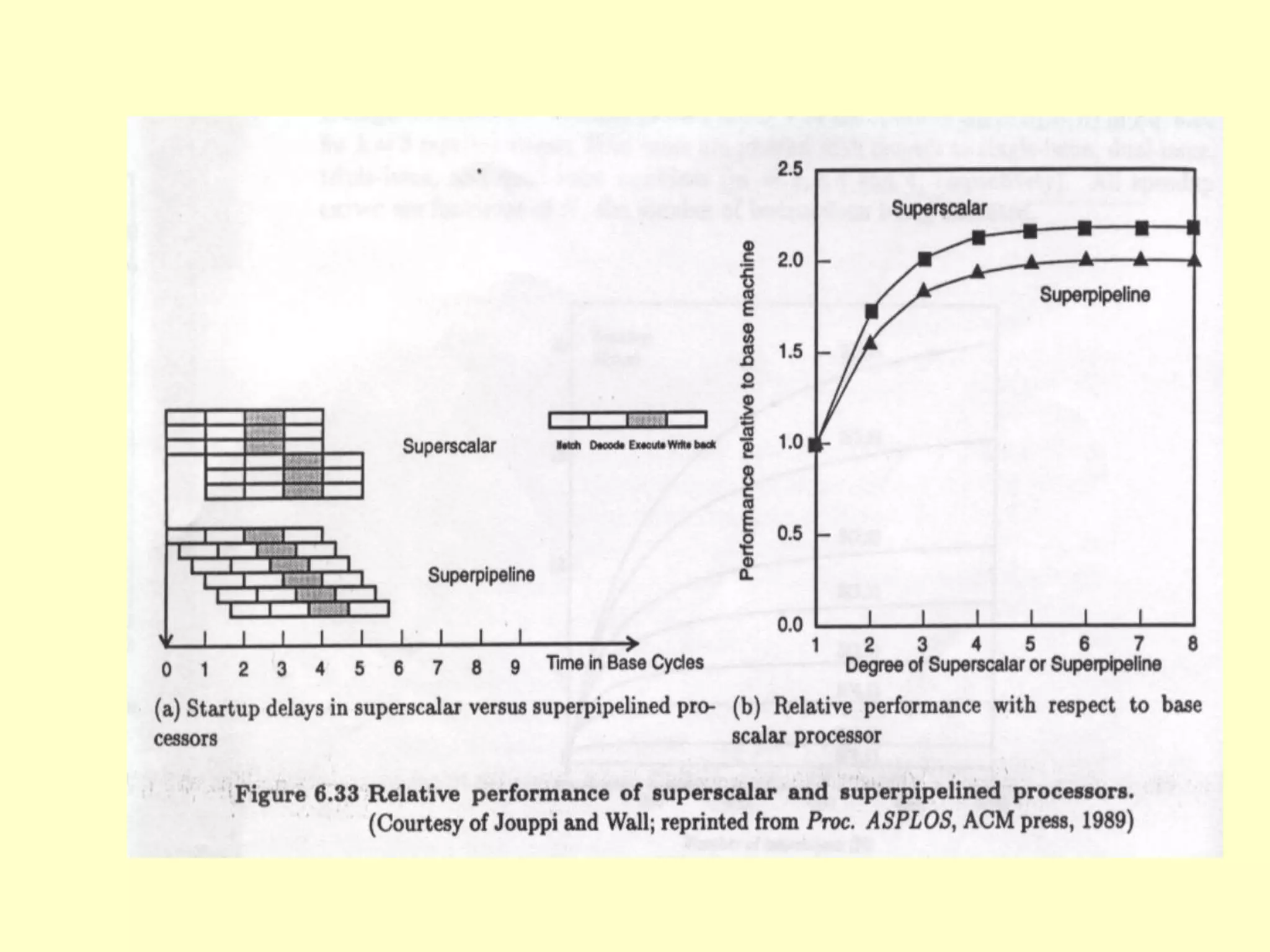

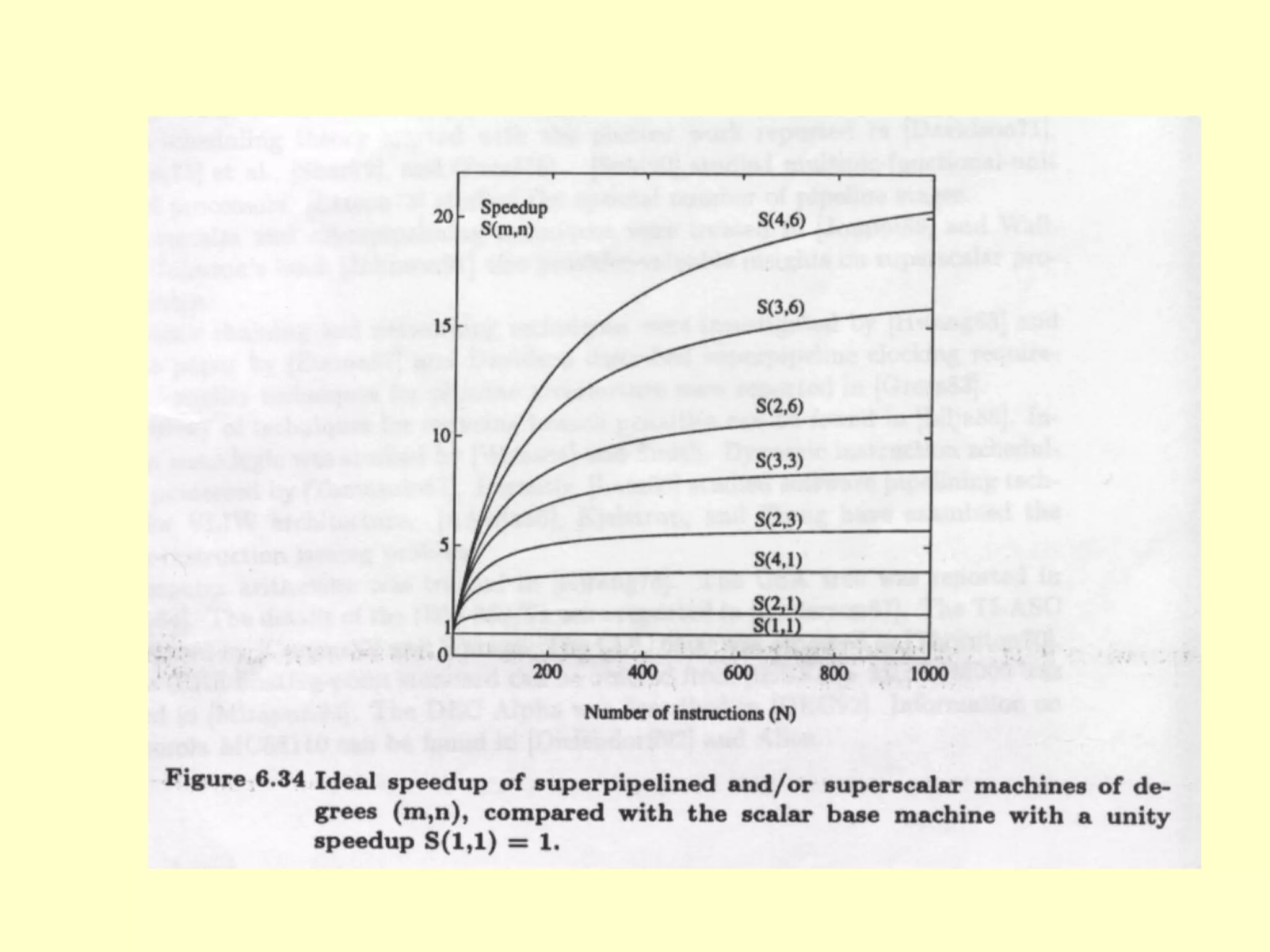

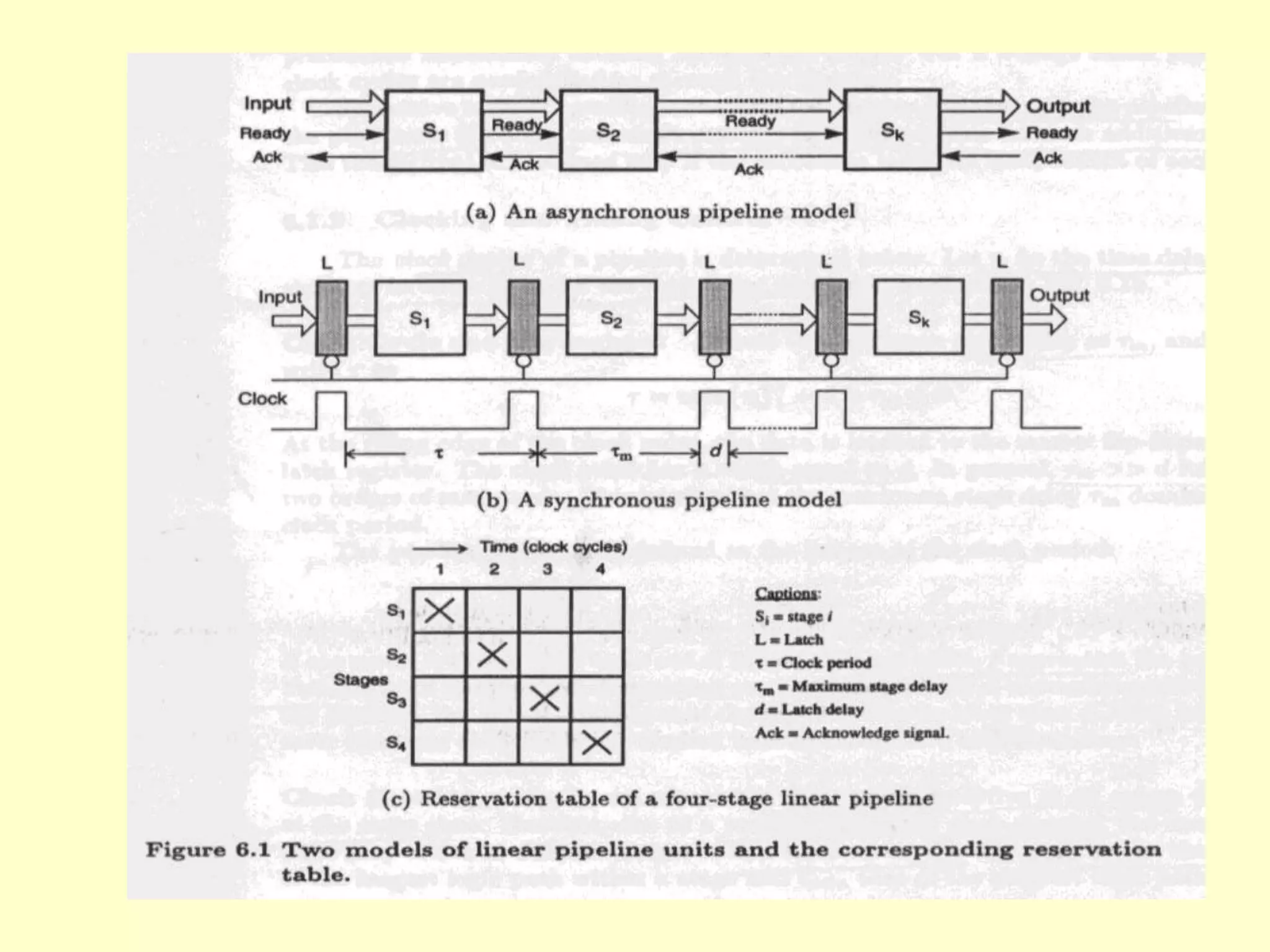

This document discusses superscalar and superpipeline processors. It covers topics like pipelining techniques, linear and nonlinear pipelines, instruction pipelines, arithmetic pipelines, superscalar design, superpipeline design, and superscalar and superpipeline tradeoffs. The key points are that superscalar design allows simultaneous execution of multiple instructions while superpipeline design uses deeper pipelines to overlap execution across multiple stages, both aim to improve processor throughput through parallelism.

![Speedup Efficiency

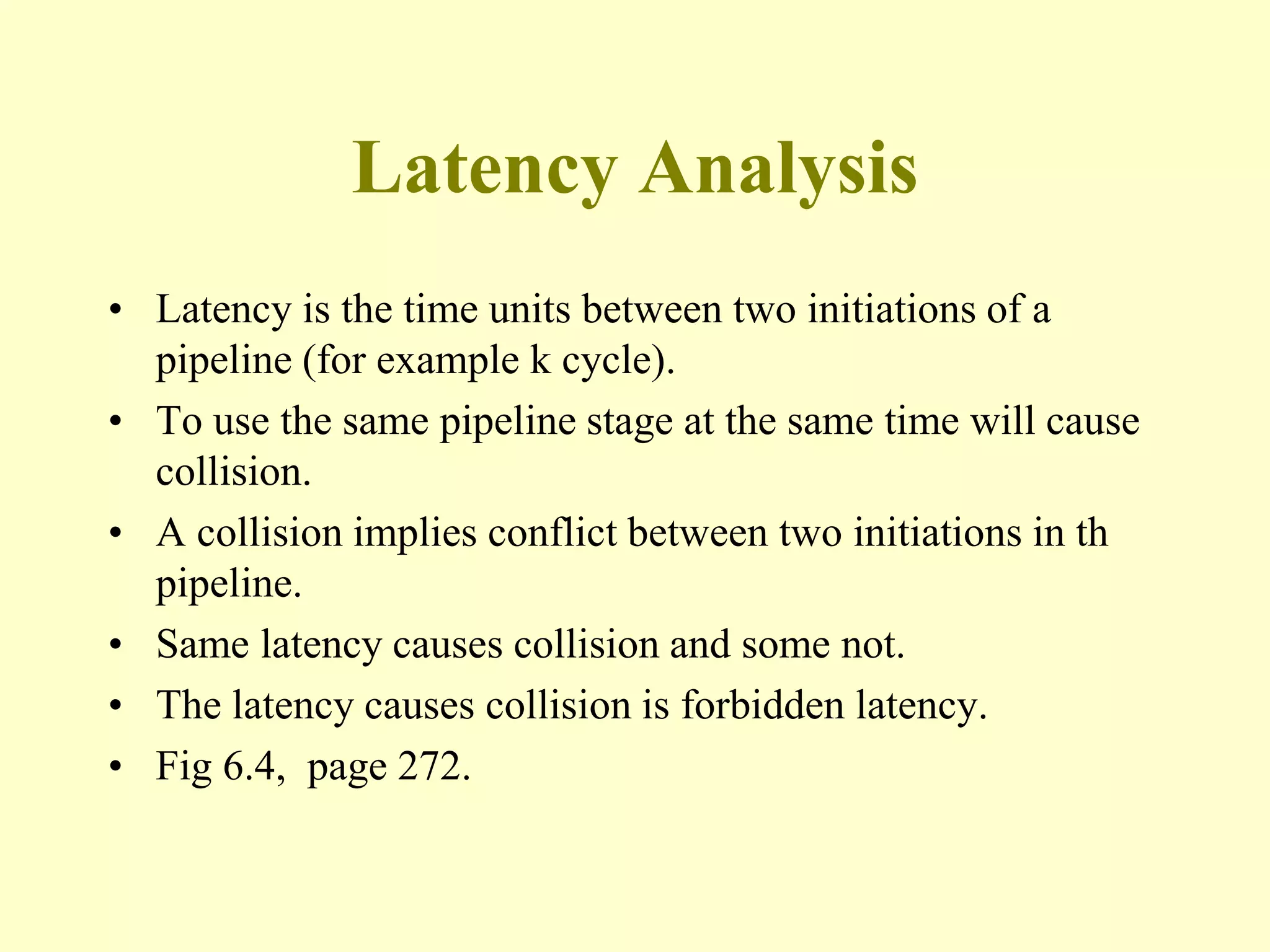

• K stages n tasks

• K+ (n-1)

• K cycle are needed to complete first task

• n-1 task require n-1 cycle, Total time

•

• Tk= [k +(n-1)]

•

• : clock period,

•

• flow throughput is;](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bil406-chapter-7-superscalarandsuperpipelineprocessors-230426175751-63286e73/75/BIL406-Chapter-7-Superscalar-and-Superpipeline-processors-ppt-14-2048.jpg)

![• Efficiency and throughput

•

• Ek = Sk/k = n /(k+(n-1))

• Ek 1; (n )

• Ek 1/k; (n 1)

•

• Hk=n/[k+(n-1)]=nf/(k+(n-1)).

• Hk Ek *f = Ek/=Sk/k; (n )

• Hk 1/k; (n 1)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bil406-chapter-7-superscalarandsuperpipelineprocessors-230426175751-63286e73/75/BIL406-Chapter-7-Superscalar-and-Superpipeline-processors-ppt-19-2048.jpg)