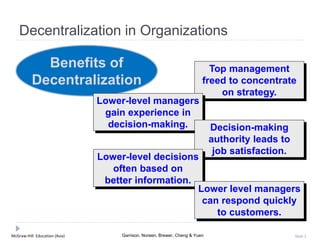

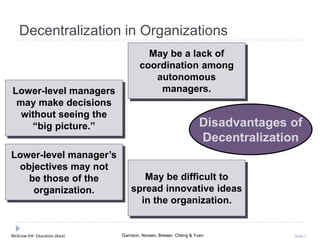

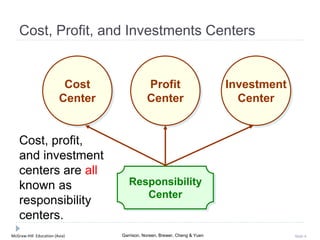

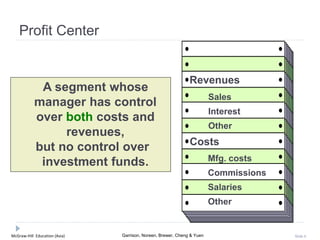

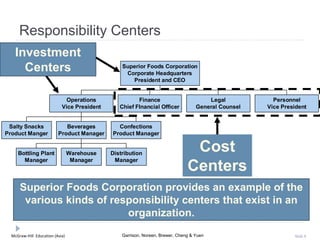

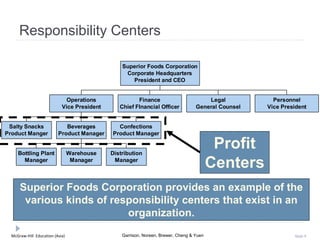

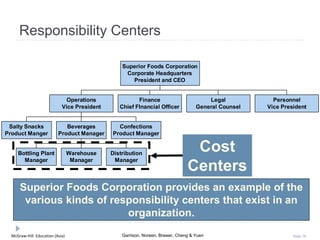

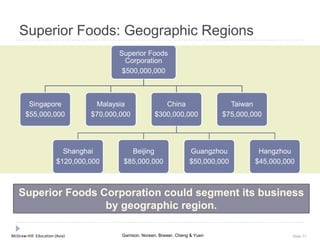

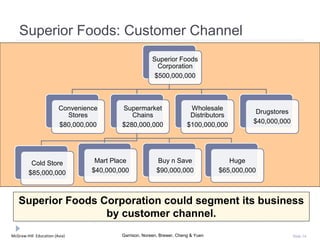

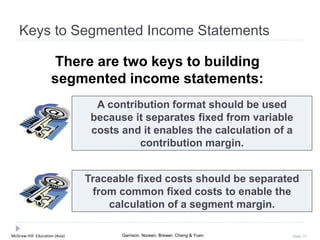

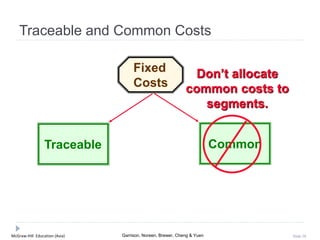

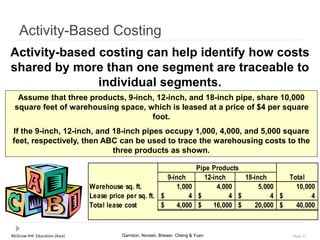

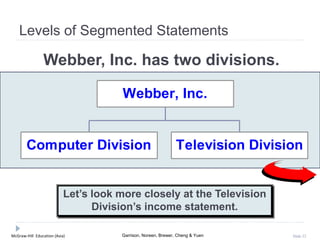

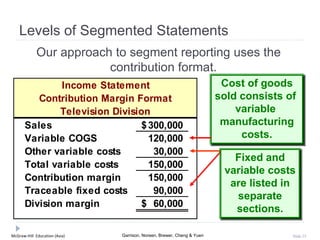

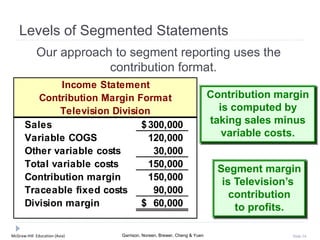

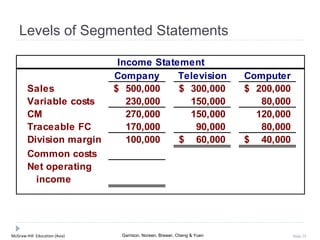

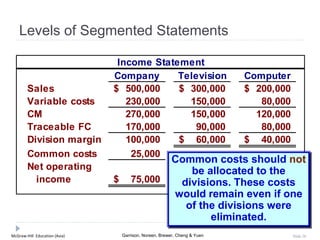

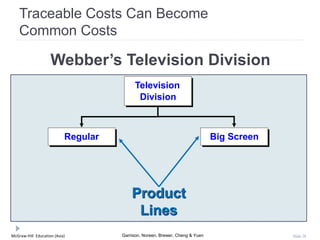

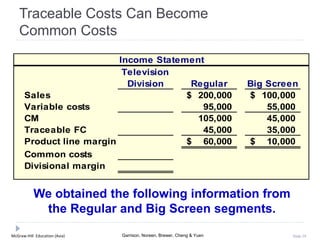

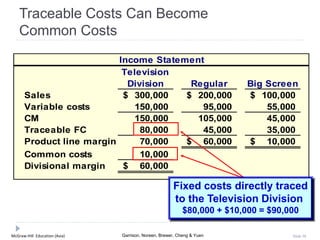

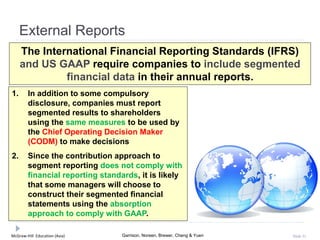

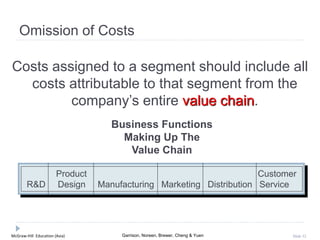

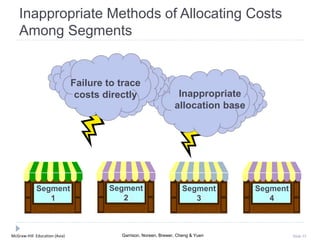

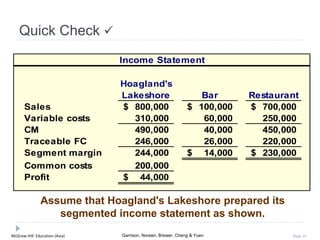

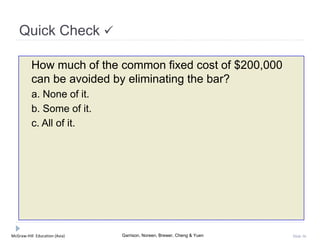

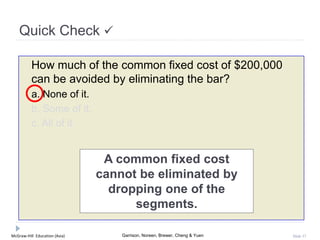

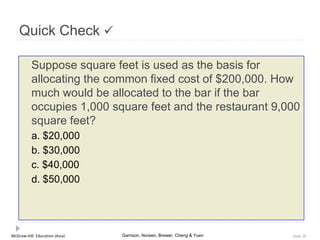

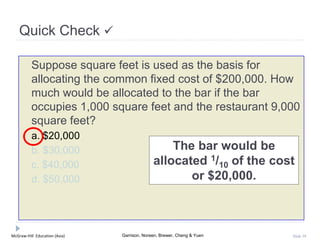

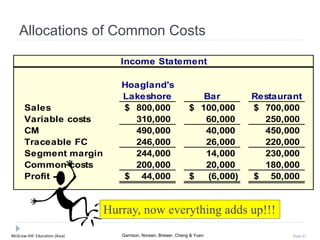

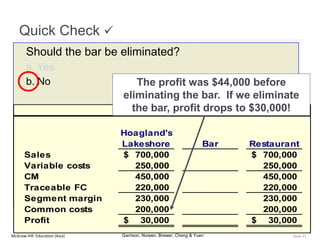

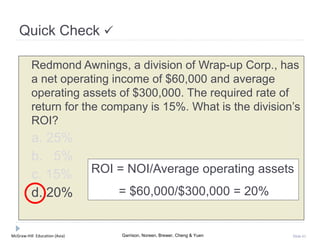

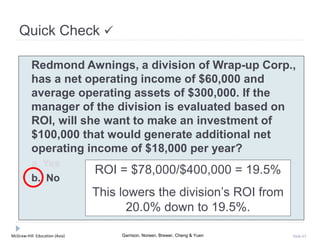

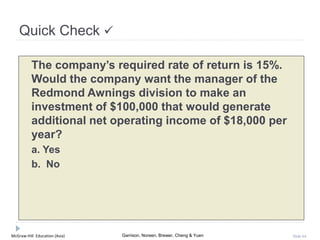

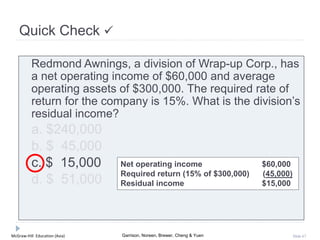

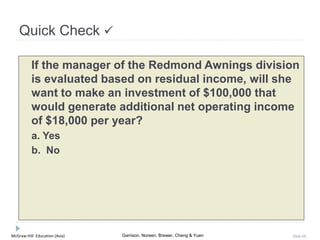

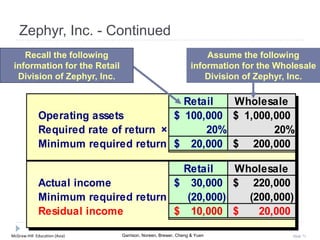

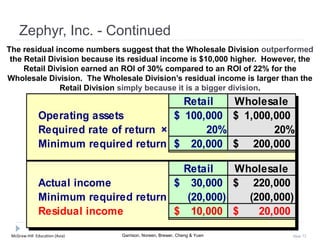

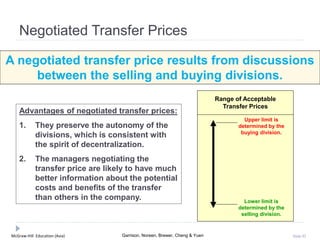

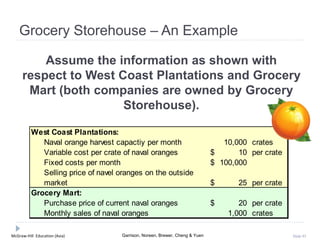

This document discusses segmentation and decentralization in organizations. It defines different types of responsibility centers such as cost centers, profit centers, and investment centers. It also discusses the benefits and disadvantages of decentralization. Additionally, it explains how to prepare segmented income statements using a contribution format by separating traceable fixed costs from common fixed costs. The document provides examples of how a company can segment its business by geographic regions or customer channels. It emphasizes that traceable costs of one segment can become common costs of another segment.