The document discusses calculating a progress measure for the sweep-line method of model checking.

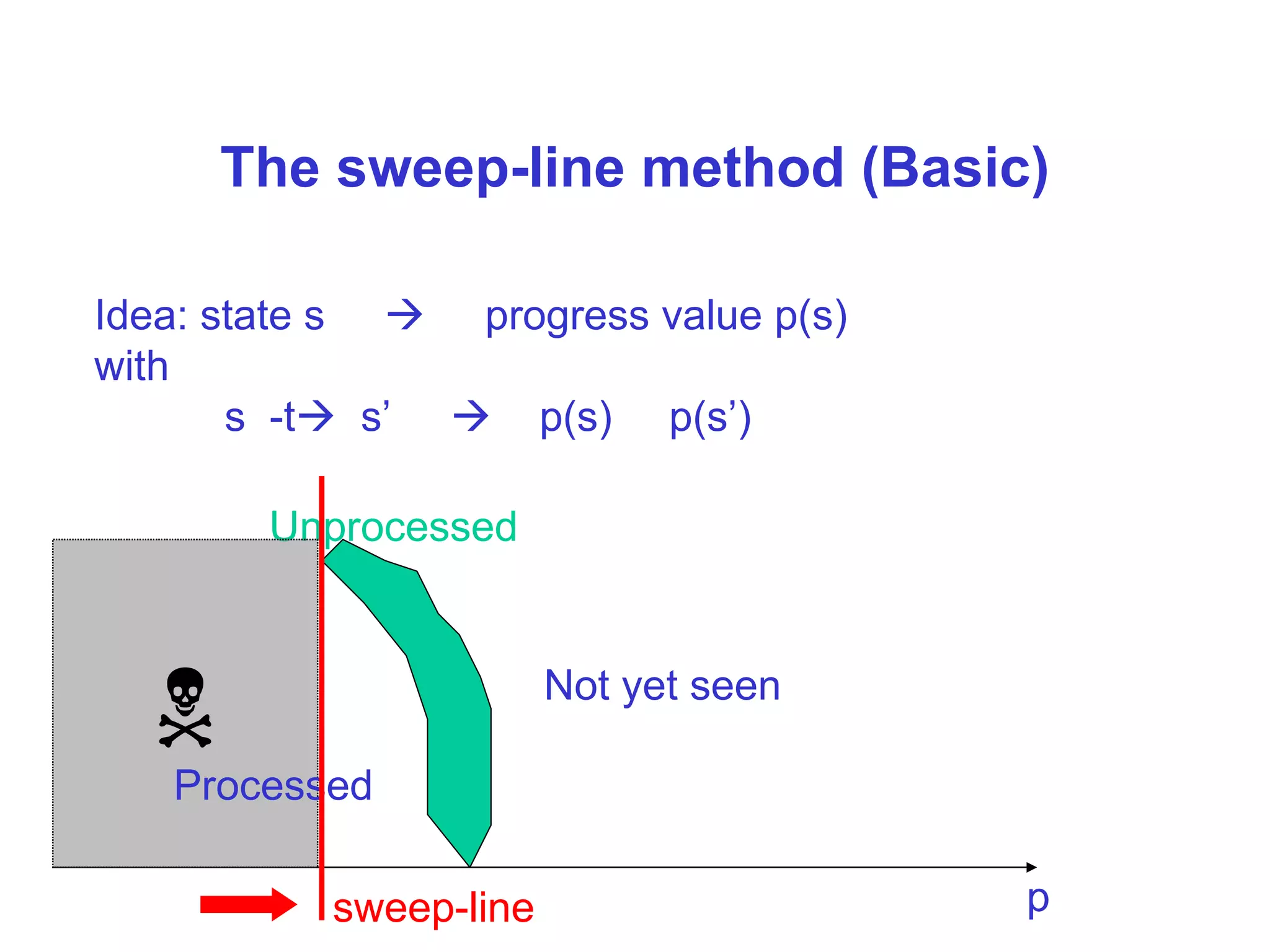

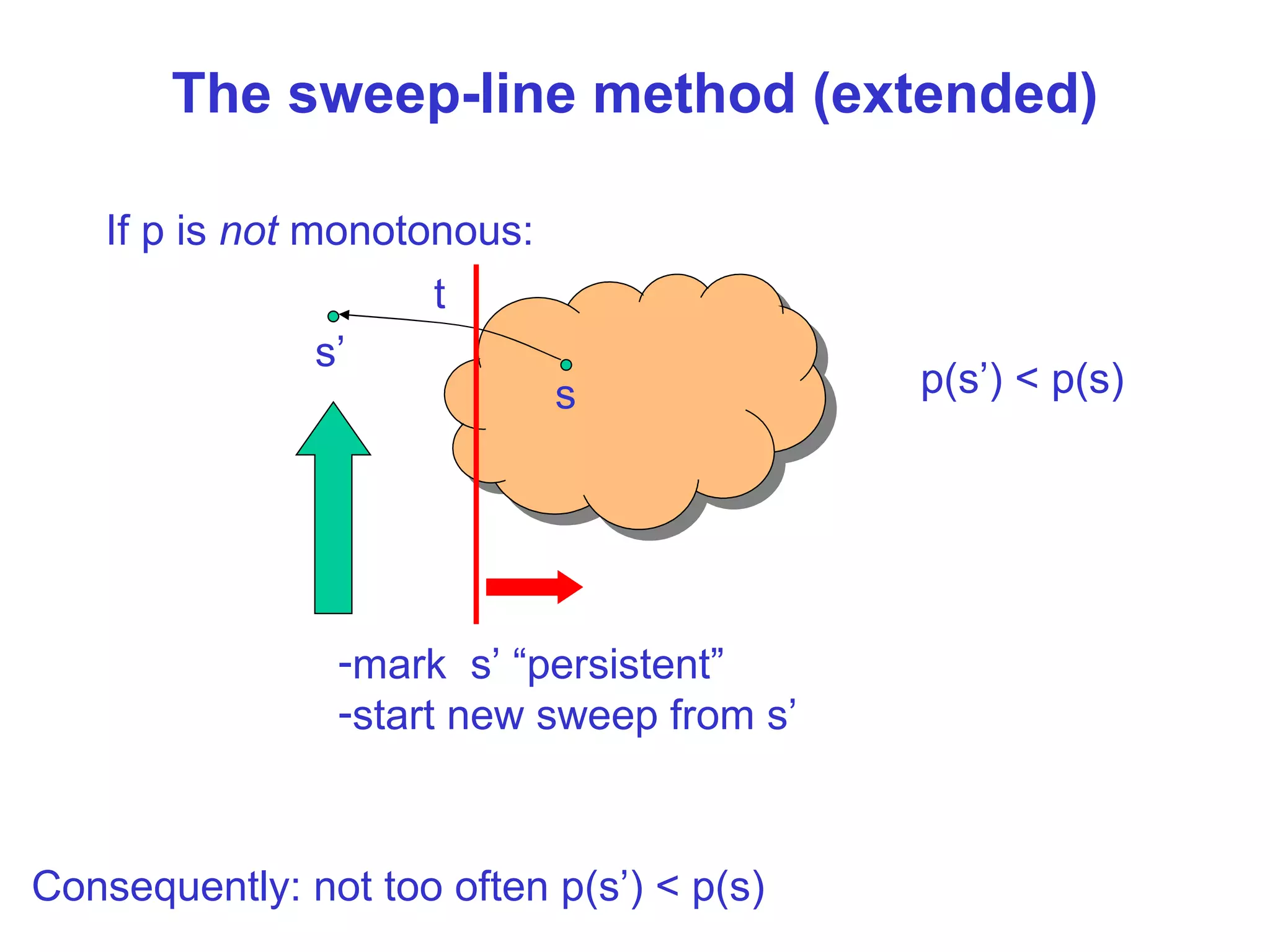

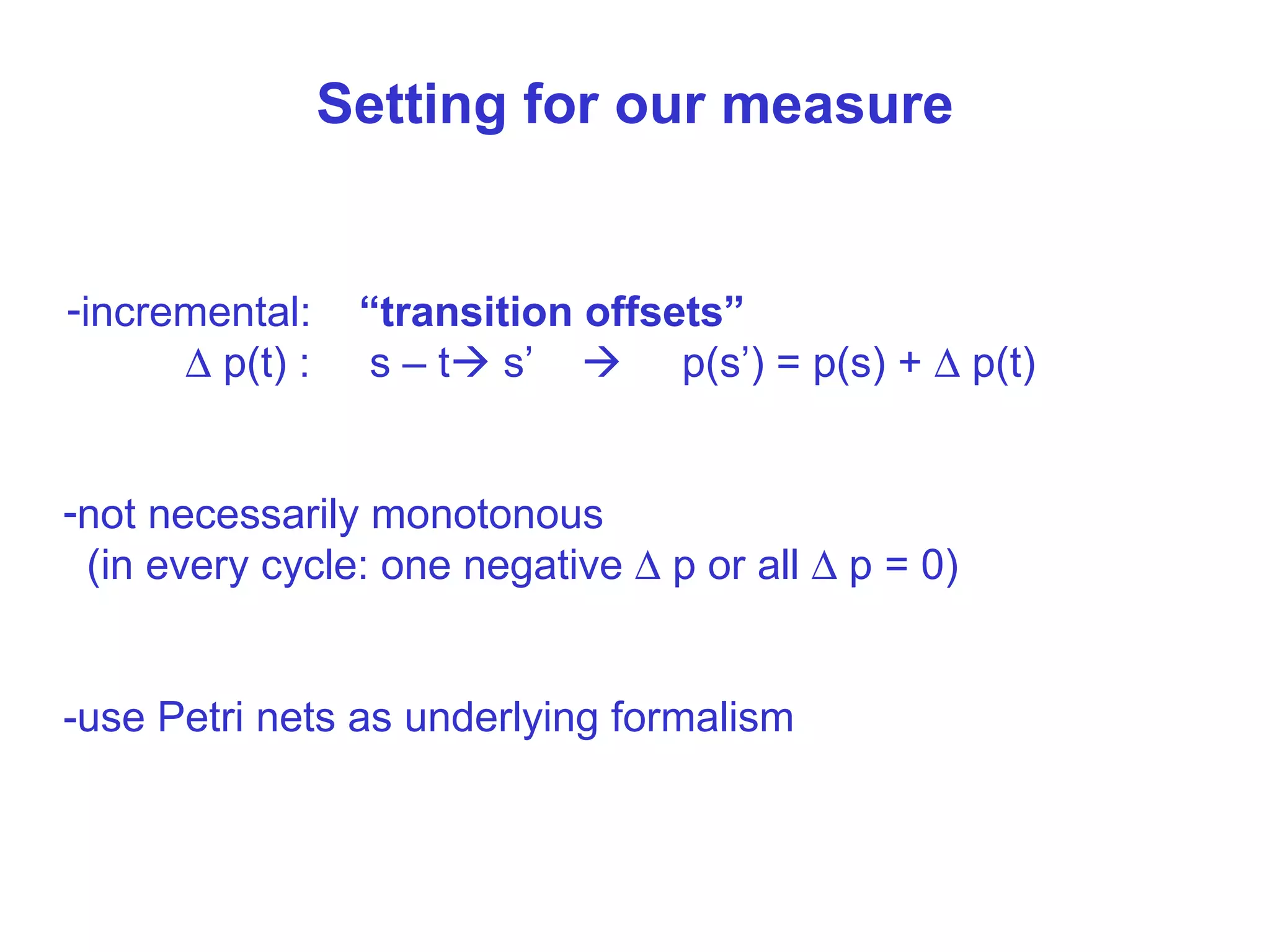

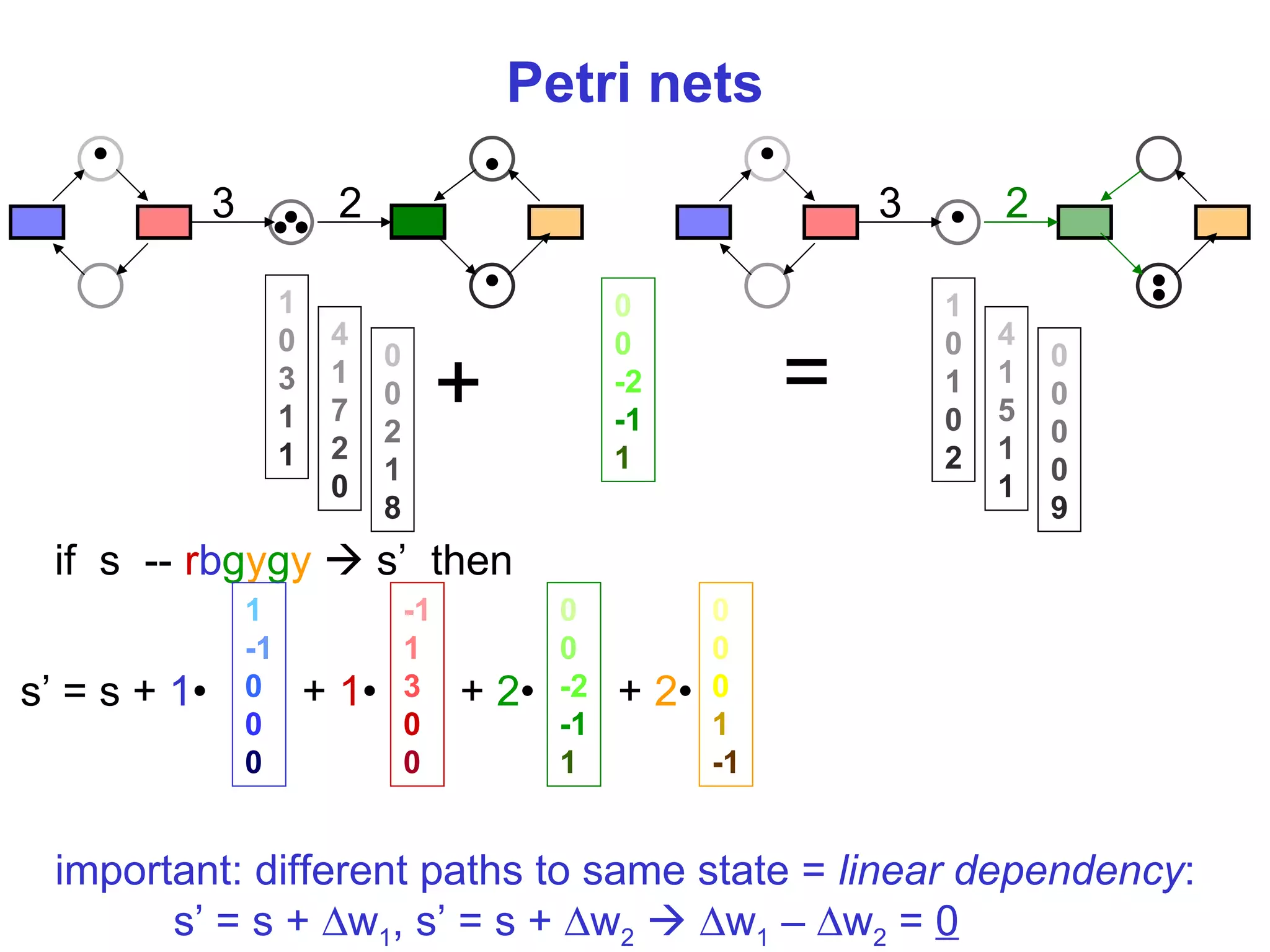

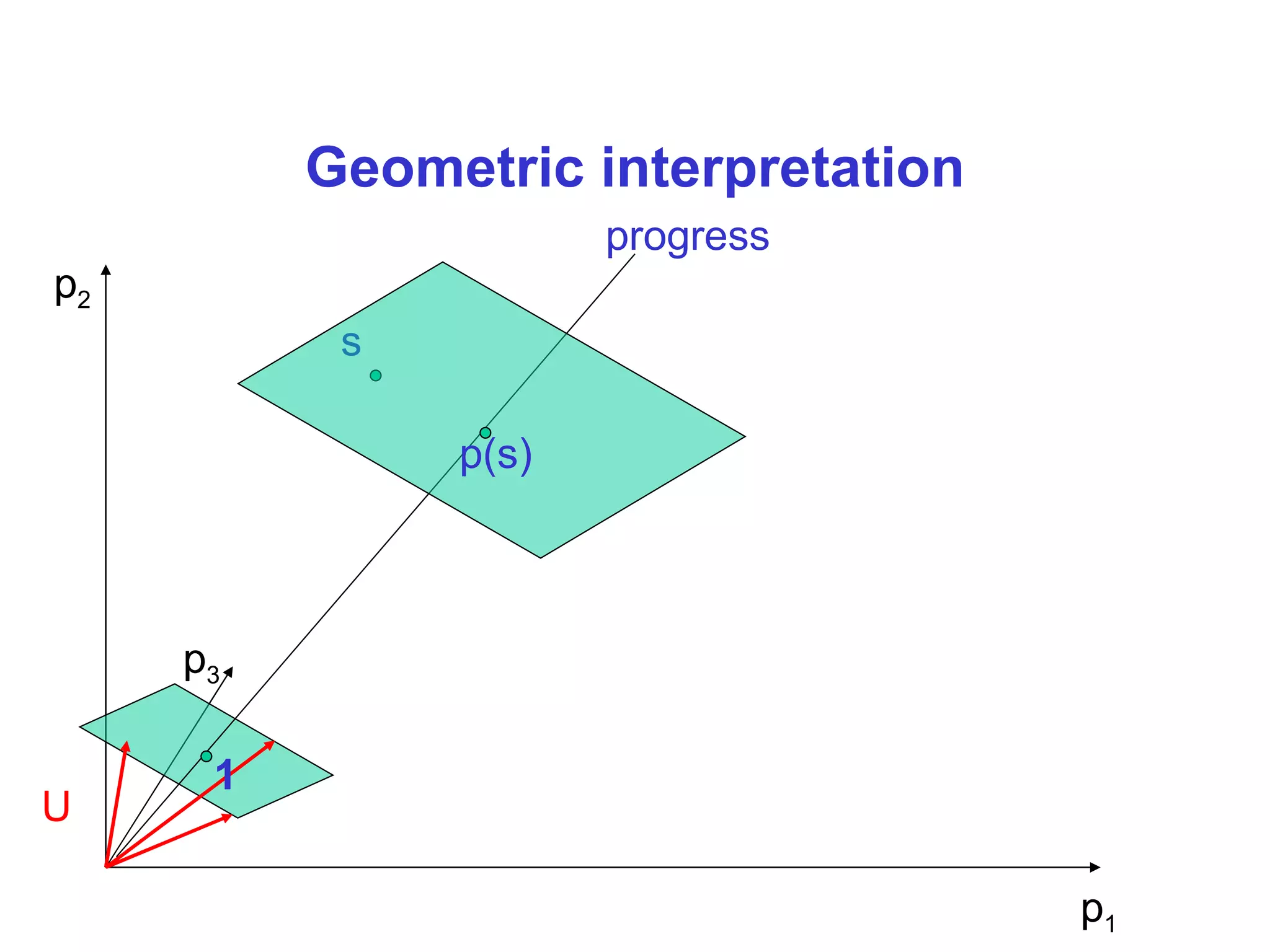

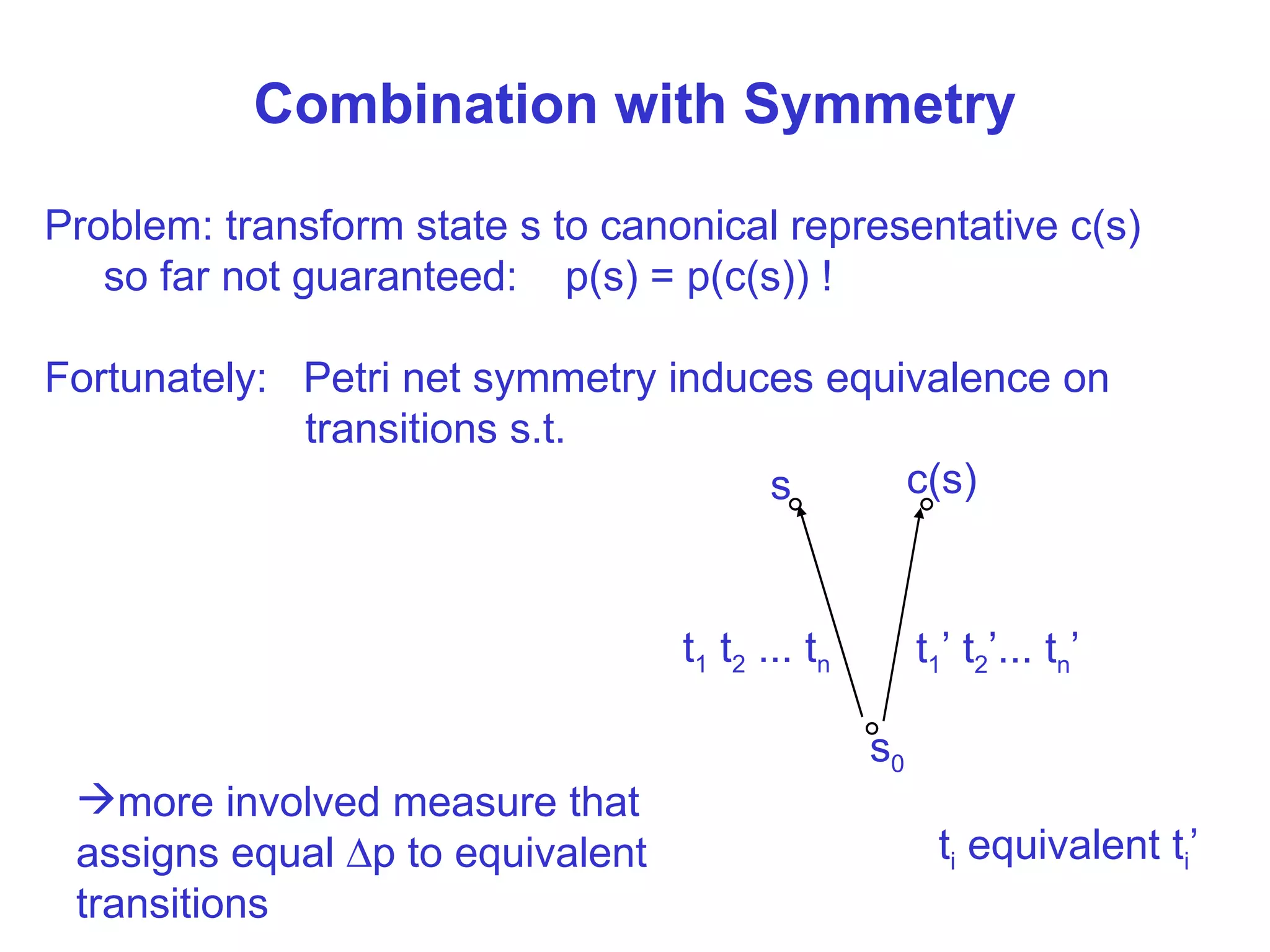

The sweep-line method works by assigning each state a progress value such that progress increases along transitions. However, progress is not always monotonic. The document proposes calculating incremental transition offsets to define progress such that it is not necessarily monotonic but increases overall.

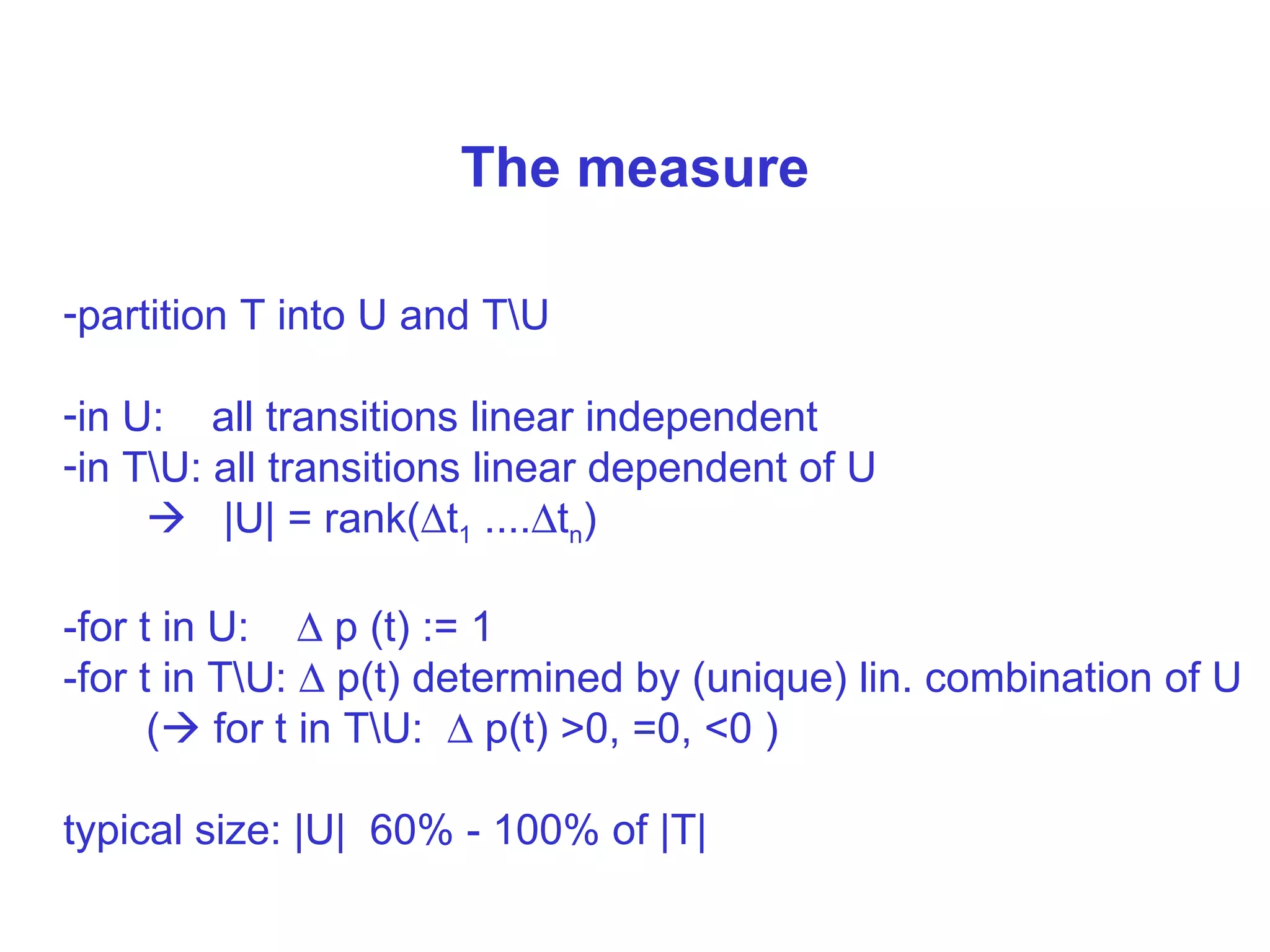

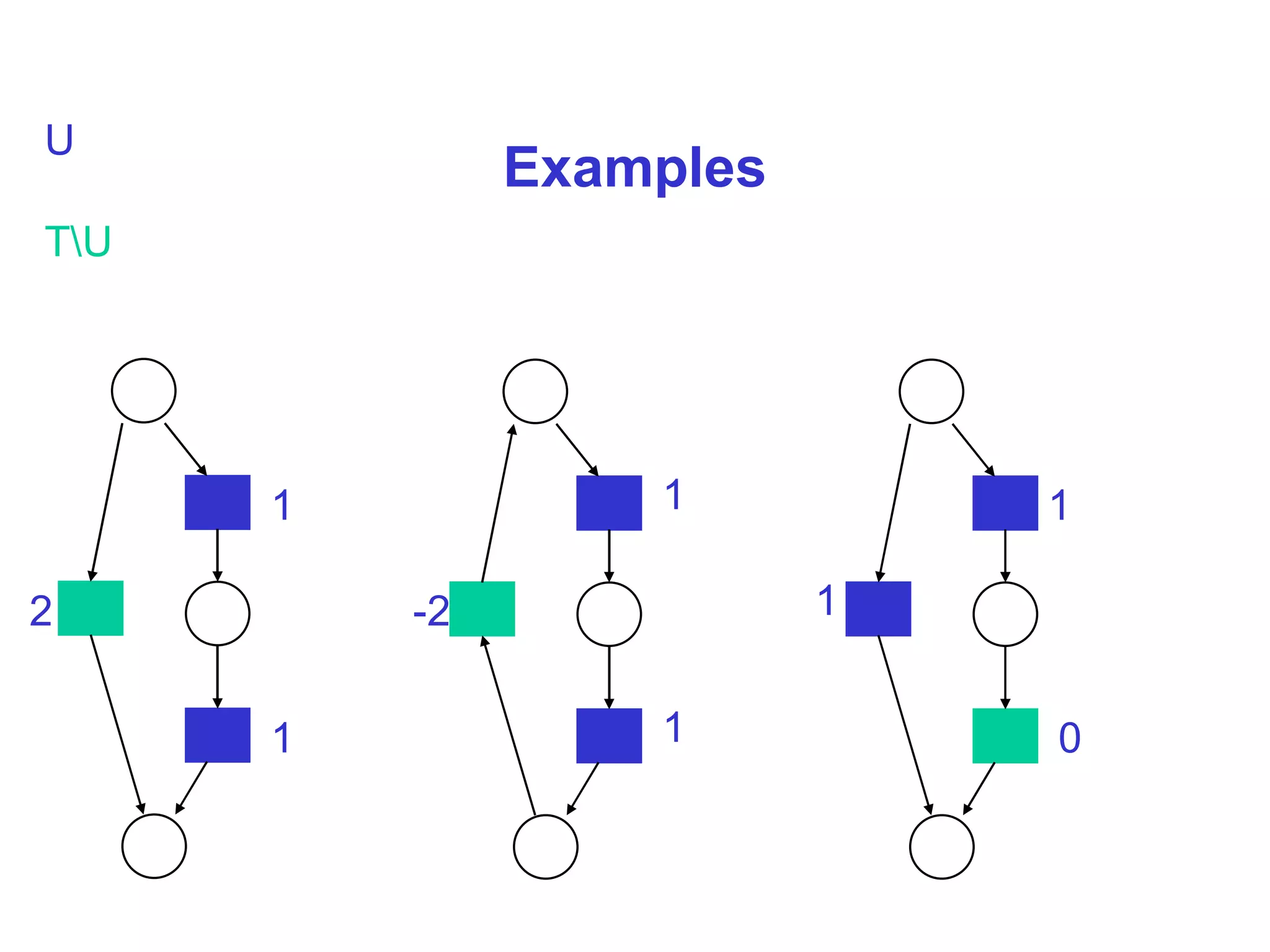

It describes partitioning transitions into independent and dependent sets and assigning offsets of 1 and determined combinations respectively to define the progress measure. This captures progress while addressing non-monotonicity in a way that is typically efficient.

![Sometime it’s good to forget... A) store only important states - branching - cover all cycles B) throw away if they cease to be useful (*) - the sweep-line method [Mailund] (*) by help of a progress measure](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tacas2004-090914060751-phpapp02/75/Automated-Calculation-of-a-Progress-Measure-of-the-Sweep-Line-Method-2-2048.jpg)