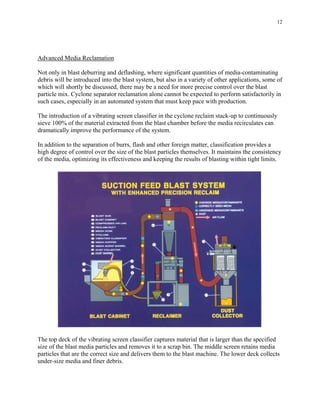

The document discusses automated blasting techniques for controlling surface texture and finish. It begins by describing the fundamentals of dry blast media and media delivery, including the main types of suction-feed and pressure-feed blast systems. It explains that automated blasting is often the fastest and most cost-effective method for production surface preparation and cosmetic finishing when it can perform the required work. The document emphasizes that proper understanding of basic blast operating principles is important for effective application of surface treatment techniques.