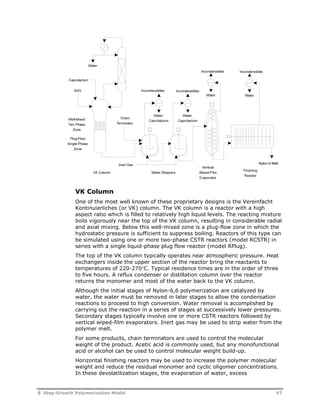

This document provides an overview of Aspen Polymers, a software package for modeling polymerization processes. It discusses Aspen Polymers tools for characterizing polymer components and their properties, modeling reaction kinetics, and building steady-state process flowsheets. The document also provides references for related documentation on using Aspen Polymers.

![Further, the assumption that polymer molecules are conserved once they are

formed can be invalid in the presence of certain side reactions, including

random (thermal) scission, which destroys polymer molecules, and chain

transfer to polymer, which causes inactive polymer molecules to become

active again, leading to long-chain branch formation and significantly

increasing the weight-average molecular weight and PDI. The molecular

weight distribution charts display the MWW and PDI calculated by the method

of moments and the method of instantaneous properties. If the predicted

values for the PDI are not in reasonable agreement with each other, it is most

likely due to these types of side reactions.

In the simplest case, linear polymerization in a single CSTR reactor, the ratios

of termination and chain transfer reaction rates to propagation reaction rates

are stored. The instantaneous chain length distribution is expressed as a

function of these ratios and chain length.

For the case of two CSTRs in series, at steady-state, the outlet polymer

distribution function is the weighted average of the distribution function in

each CSTR taken separately. The case of a plug flow reactor can be

approximated using multiple CSTRs, and similarly for a batch reactor.

By looking at the treatment of such reactor configurations, it can be deduced

that the final polymer distribution is a result of the entire system of reactors.

For this reason, the MWD implementation in Aspen Polymers needs to

consider the proper data structure to track distribution parameters at every

point in the flowsheet. Users should be able to request MWD from any point in

the flowsheet, and from this point the Aspen Plus flowsheet connectivity

information can be used to track polymerization history.

The calculation of chain length distribution for a batch reactor from reaction

rate parameters for linear addition polymerization was described by Hamielec

(Hamielec, 1992).

Consider the equations for the generation and consumption of free radicals. A

similar approach may be used for other active centers (Ziegler-Natta,

metallocene, etc.):

Radical Generation and Consumption Rates

R K [ M ][ R o

]

K [ T ][ R

o

]

I fm

fT

K [ M ] K [ M ] K [ T ] K

K [ R

o

]

p fm fT tc td

l

o

R

o

K M R

[ ][ 1]

p

r

K [ M ] K [ M ] K [ T ] K

K [ R

o

]

p fm fT tc td

r

o

R

Where:

R K f I I d 2 [ ] = Initiation rate

Instantaneous Distribution Parameters

Introducing two dimensionless parameters and .

5 Structural Property Distributions 61](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/aspenpolymersunitopsv82-usr-141128134016-conversion-gate02/85/Aspen-polymersunitopsv8-2-usr-73-320.jpg)

![

o

R

R

R

K R K M K T

[ ] [ ] [ ]

fm fT

p

K M

td f

p

td

[ ]

R

R

tc

p

o

K R

tc

K M

p

[ ]

[ ]

Where:

R K R M p p

[ o ][ ] = Propagation rate

R K R td td

[ o ]2 = Rate of termination by disproportionation

R K [ R o ]2 = Rate of termination by combination

tc tc

R K R M K R T f fm

[ o

][ ] [ o ][ ] = Total rate of chain transfer to

fT

small molecules (not

polymers)

If we assume that the stationary-state hypothesis holds, then the initiation

rate is equal to the sum of the termination rates, RI Rtd Rtc .

The equations for the rate of generation and consumption of radicals can be

written as follows:

Ro R

l

1

o

1

Ro R o

r

r

1

1 Therefore:

Ro r

R

o r

Where:

1

1

The rate of production of polymer molecules of chain length r , RFp (r) is

given by:

1 1

r

1

R ( r ) r

K M K T K R o R o

K R o

s

R

FP

r s

V

d V P

dt

fm fT td

r tc

2 s

1

o

Substituting [ ] Rf o

gives:

2

R r K R M r FP p

( ) o

1

r

62 5 Structural Property Distributions](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/aspenpolymersunitopsv82-usr-141128134016-conversion-gate02/85/Aspen-polymersunitopsv8-2-usr-74-320.jpg)

![Reaction

Type Reaction Stoichiometry

Acetaldehyde

Formation

Cyclic Trimer

Formation

O O

C C

O O

U5

O(CH2)2OH C C

O

OH + HCCH3

O

HCCH3

O O

O O

U6

O(CH2)2OH + OCH CH2 C C

C C +

O(CH2)2O

U7

U8

G T

HOT G T G T GH + H2O

T

G T

G

U9

U10

G T

HG T G T G T GH + HO(CH2)2OH

T

G T

G

U11

U12

G T

T

G T

G

G T G T G T GH O(CH2)2OH +

The recommended power-law exponents for the reactants in the side

reactions are:

Reaction

No. Power-Law Exponents; Modeling Notes

U1 EG = 2 (Multiply group-based pre-exponential factor by 4.0)

U2 EG = 1, T-EG = 1 (Multiply group-based pre-exponential factor by

2.0)

U3 T-EG = 2 (Multiply group-based pre-exponential factor by 1.0)

U4 Reaction is first order with respect to polyester repeat units, assume

concentration of repeat units is approximately equal to the

concentration of B-TPA, set power-law exponents B-TPA = 1.0 B-EG =

1x10-8

U5 T-EG = 1

U6 T-EG = 1, T-VINYL = 1

U7 Reaction is first order with respect to linear molecule with the

following segment sequence:

T-TPA: B-EG : B-TPA : B-EG : B-TPA : T-EG

option 1: assume this concentration = TPA concentration and use

power-law constant TPA = 1*

option 2: use the following equation, based on the most-probable

distribution, to estimate the concentration of this linear oligomer. This

equation can be implemented as a user-rate constant correlation

P

[ ] [ ] [ ] [ ] [ ] [ ] *[ ] *[

T EG

NUCL

B TPA

ELEC

2 2

B EG

NUCL

T TPA

ELEC

NUCL T EG T DEG B EG

2 2

2

2 0

ELEC T TPA B TPA

[ ] *[ ]

U8 H2O = 1, C3 = 1 (Multiply group-based pre-exponential factor by 6.0)

110 8 Step-Growth Polymerization Model](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/aspenpolymersunitopsv82-usr-141128134016-conversion-gate02/85/Aspen-polymersunitopsv8-2-usr-122-320.jpg)

![Reaction

No. Power-Law Exponents; Modeling Notes

U9 Reaction is first order with respect to linear molecule with the

following segment sequence:

T-EG : B-TPA : B-EG : B-TPA : B-EG : B-TPA : T-EG

option 1: assume this concentration = TPA concentration and use

power-law constant TPA = 1*

option 2: use the following equation, based on the most-probable

distribution, to estimate the concentration of this linear oligomer. This

equation can be implemented as a user-rate constant correlation

P

[ ] [ ] [ ] [ ] [ ] *[ ] *[ ]

T EG

NUCL

2 3 2

B TPA

ELEC

B EG

NUCL

NUCL T EG T DEG B EG B DEG

2 2

2

2 0

ELEC T TPA B TPA

[ ] *[ ]

U10 EG = 1, C3 = 1 (Multiply group-based pre-exponential factor by 12.0)

U11 Reaction is first order with respect to linear molecule with the

following segment sequence:

~B-EG : B-TPA : B-EG : B-TPA : B-EG : B-TPA : T-EG

option 1: assume this concentration = T-EG concentration and use

power-law constant T-EG = 1*

option 2: use the following equation, based on the most-probable

distribution, to estimate the concentration of this linear oligomer. This

equation can be implemented as a user-rate constant correlation

P

[ ] [ ] [ ] [ ] [ ] *[ ] *[ ]

T EG

NUCL

B TPA

ELEC

3 3

B EG

NUCL

NUCL T EG T DEG B EG B DEG

2 2

2

2 0

ELEC T TPA B TPA

[ ] *[ ]

U12 T-EG = 1, C3 = 1 (Multiply group-based pre-exponential factor by

6.0)

* To avoid numerical problems, set power-law exponents to 1108 for reactants

which do not appear in the rate expression

0 = Concentration zeroth moment, mol/L (approximately=0.5*([T-TPA]+[T-EG]+[

T-DEG]+[T-VINYL])

Nylon-6 Reaction Kinetics

Nylon-6 melt-phase polymerization reactions are initialized by the hydrolytic

scission of caprolactam rings. The reaction between water and caprolactam

generates aminocaproic acid. The reaction kinetics in the primary reactor are

sensitive to the initial water concentration.

The carboxylic and amine end groups of the aminocaproic acid molecules

participate in condensation reactions, releasing water and forming polymer

molecules. The resulting acid and amine end groups in the polymer react with

each other and with aminocaproic acid, releasing more water.

The amine end of aminocaproic acid and amine ends in polymer react with

caprolactam through ring addition. This reaction is the primary growth

mechanism in the nylon-6 process.

8 Step-Growth Polymerization Model 111](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/aspenpolymersunitopsv82-usr-141128134016-conversion-gate02/85/Aspen-polymersunitopsv8-2-usr-123-320.jpg)

![Reaction

No. Power-Law Exponents; Modeling Notes

U2 reverse Reaction is first order with respect to linear dimer P2 with the following segment

sequence:

T-NH2 :T-COOH

option 1: assume P2 concentration = ACA concentration and use power-law constant

ACA = 1*

option 2: use the following equation, based on the most-probable distribution, to

estimate concentration of P2 The denominator in this equation can be implemented

as a user rate constant, with first-order power-law constants for T-NH2 and T-COOH.

P

[ T

NH

2

]

[

]

2 T NH R NY

T COOH R NY 0

T COOH

[ ] [ ]

2 6 6

[ ] [

]

U3 forward ACA = 1, CL = 1

U3 reverse See U2 reverse reaction

U4 forward T-NH2 = 1, CL = 1

U4 reverse T-NH2 = 1 (this approximation assumes most T-NH2 end groups are attached to

repeat units)*

U5 forward ACA = 1, CD = 1

U5 reverse Reaction is first order with respect to linear trimer P3 with the following segment

sequence:

T-NH2 : R-NY6 : T-COOH

option 1: assume P3 concentration = ACA concentration and use power-law constant

ACA = 1*

option 2: use the following equation, based on the most-probable distribution, to

estimate concentration of P3 The denominator in this equation can be implemented

as a user rate constant, with first-order power-law constants for T-NH2, R-NY6, and

T-COOH.

[ T

NH

2

]

[ 6

]

P

[

]

2 T NH R NY

T COOH R NY 0

R NY

T COOH R NY

T COOH

[ 2 ] [ 6

]

[ ] [ ]

6 6

[ ] [

]

U6 forward T-NH2 = 1, CD = 1

U6 reverse T-NH2 = 1 (this approximation assumes most T-NH2 end groups are attached to

repeat units)*

*

To avoid numerical problems, set power-law exponents to 1108 for reactants which do not

appear in the rate expression

0 = Concentration zeroth moment, mol/L (approximately = 0.5 * ([T-COOH] + [T-NH2])

The side reactions are thought to be catalyzed by acid end groups in

aminocaproic acid and the polymer. A first-order power-law coefficient can be

used to account for the influence of the acid groups in these components.

Alternately, a user rate-constant subroutine can be developed to account for

the influence of the acid end groups.

Note that the forward and reverse terms of the reversible side reactions must

be defined as two separate user reactions in the model.

114 8 Step-Growth Polymerization Model](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/aspenpolymersunitopsv82-usr-141128134016-conversion-gate02/85/Aspen-polymersunitopsv8-2-usr-126-320.jpg)

![Reaction

No. Power-Law Exponents; Modeling Notes

U1 forward HMDA = 1, ADA = 1 Multiply group-based pre-exponential factor by 4.0

U1 reverse H2O = 1, DIS-SALT = 1

U2 forward DIS-SALT = 2

U2 reverse Reaction is first order with respect to water and polymer molecule P4 with the

following segment sequence:

T-HMDA : B-ADA : B-HMDA : T-ADA

option 1: assume P4 concentration = DIS-SALT concentration and use DIS-SALT =

1, H2O = 1*

option 2: set power-law exponent for H2O = 1 and use the following equation, based

on the most-probable distribution, to estimate concentration of P4 (this equation can

be implemented as a user rate constant).

0

P T ADA

4

B HMDA

2[

]

T HMDA B HMDA

[ ] 2[

]

T HMDA

[

]

T HMDA B HMDA

[ ] 2[ ]

[

]

T ADA B ADA

[ ] 2[

]

B ADA

2[

]

T ADA B ADA

[ ] 2[ ]

U3 forward DIS-SALT = 1, ADA = 1, multiply group rate constant by 2.0

U3 reverse Reaction is first order with respect to water and polymer molecule P 3,aa with the

following segment sequence:

T-ADA : B-HMDA : T-ADA

option 1: assume P 3,aa concentration = ADA concentration and use power-law

constants ADA = 1, H2O = 1*

option 2: set power-law exponent for H2O = 1 and use the following equation, based

on the most-probable distribution, to estimate concentration of P 3,aa (this equation

can be implemented as a user rate constant).

[ T

ADA

]

2

2

[ ]

P

3 aa T ADA B ADA

T HMDA B HMDA

B HMDA

, 2

2 0

[ ] [ ]

[ ] [ ]

U4 forward DIS-SALT = 1, HMDA = 1; multiply group rate constant by 2.0

U4 reverse Reaction is first order with respect to water and polymer molecule P 3,BB with the

following segment sequence:

T-HMDA : B-ADA : T-HMDA

option 1: assume P 3,BB concentration=HMDA concentration and use power-law

constants HMDA=1, H2O=1*

option 2: set power-law exponent for H2O = 1 and use the following equation, based

on the most-probable distribution, to estimate concentration of P 3,BB (this equation

can be implemented as a user rate constant).

[ T

HMDA

]

2

2

[ ]

P

3 aa T HMDA B HMDA

T ADA B ADA

B ADA

, 2

2 0

[ ] [ ]

[ ] [ ]

U5 forward DIS-SALT = 1, T-ADA = 1

U5 reverse H2O = 1, T-ADA = 1, set power law constants for B-ADA, B-HMDA to 1E-10 to avoid

numerical problems

U6 forward DIS-SALT = 1, T-HMDA = 1

120 8 Step-Growth Polymerization Model](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/aspenpolymersunitopsv82-usr-141128134016-conversion-gate02/85/Aspen-polymersunitopsv8-2-usr-132-320.jpg)

![Reaction

No. Power-Law Exponents; Modeling Notes

U6 reverse H2O = 1, T-ADA = 1, set power law constants for B-ADA, B-HMDA to 1E-10 to avoid

numerical problems

*

To avoid numerical problems, set power-law exponents to 1108 for reactants

which do not appear in the rate expression

0 = Concentration zeroth moment, mol/L (approximately = 0.5 * ([T-ADA] + [T-HMDA])

8 Step-Growth Polymerization Model 121](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/aspenpolymersunitopsv82-usr-141128134016-conversion-gate02/85/Aspen-polymersunitopsv8-2-usr-133-320.jpg)

![Symbol Description

[Nucl] Concentration of the attacking nucleophilic species, mol/L*

[Elec] Concentration of the attacking electrophilic species, mol/L*

fn

Number of electrophilic leaving groups in the attacking nucleophilic species.

This factor is 2 for diol and diamine monomers.

fe In reactions involving two victim species, fe is the number of electrophilic

groups in the electrophilic species. This factor is 2 for repeat units which

contain EE-GRP groups.

In reactions involving one victim species, fe is the number of nucleophilic

leaving groups in the electrophilic species. This factor is 2 for diacid, diester,

and carbonate monomers.

P In reactions involving two victim species, P is the probability of the victim

nucleophilic species being adjacent to the victim electrophilic species. This

probability factor is calculated by the model assuming the most probable

distribution:

P

f N

f N

vns vns

i i i

where:

fvns = Number of similar points of attachment in victim nucleophilic segment

(= 2 for NN-GRP repeat segments, 1 for all others)

Nvns = Concentration of victim nucleophilic segment

i = Index corresponding to list of all nucleophilic segments

i Index corresponding to the rate constant set number. The summation is

performed over the specified list of rate constant set numbers.

Symbol Description

Ci

Catalyst concentration for rate constant set i. If the catalyst species is

specified, this is the concentration of the species. If the catalyst group is

specified, this the group concentration. If both species and group are specified,

this is the concentration of the species times the number of the specified group

in the specified species. If the catalyst is not specified, this factor is set to one.

ko

Pre-exponential factor in user-specified inverse-time units*

Ea Activation energy in user-specified mole-enthalpy units (default =0)

b Temperature exponent (default = 0)

R Universal gas constant in units consistent with the specified activation energy

T Temperature, K

Tref

Optional reference temperature. Units may be specified, and they are

converted to K inside the model.

flag User flag for rate constant set i. This flag points to an element of the user rate

constant array.

U User rate constant vector calculated by the optional user rate constant

subroutine. The user flag indicates the element number in this array which is

used in a given rate expression. When the user flag is not specified, or when

the user rate constant routine is not present, this parameter is set to 1.0.

* The concentration basis may be changed to other units using the Concentration

basis field on the Options sheet or using the optional concentration basis

subroutine.

134 8 Step-Growth Polymerization Model](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/aspenpolymersunitopsv82-usr-141128134016-conversion-gate02/85/Aspen-polymersunitopsv8-2-usr-146-320.jpg)

![User Reactions

The model cannot predict all types of reactions based on the specified

structures. Reactions which are not predicted by the model can be included as

user-specified reactions. These can include thermal scission reactions,

monomer or segment reformation, end-group modification, etc.

The user-specified reactions apply a modified power-law rate expression, as

shown here:

Equation

b

Ea

1 1

i

k Catalyst k e T

i

Tref specified i

net i i o i U flag

T

ref

R T T

ref

, [ ]

Ea

i

Tref unspecified i

k [ Catalyst ] k e RT b

iU flag

net ,

i i o i T Assign User Rate Constants is used: rate activity C a

mj k

m m j j i net ,

i

rate a

Assign User Rate Constants is not used: C mj k (m i) m j j

net ,

i

Nomenclature

Symbol Description

m User reaction number

i Rate constant set number

j Component number

Product operator

Cj

Concentration* of component j, mol/L

i

Catalyst order term for catalyst i (default = 1)

mj Power-law exponent for component j in reaction m

ko

Pre-exponential factor in user-specified inverse-time and concentration units*

net ,i k Net rate constant for set i

Ea Activation energy in user-specified mole-enthalpy units (default =0)

b Temperature exponent (default = 0)

R Universal gas constant in units consistent with the specified activation energy

T Temperature, K

Tref

Optional reference temperature. Units may be specified, they are converted to K in the

model.

flag User flag for rate constant set i. This flag points to an element of the user rate constant

array.

U User rate constant vector calculated by the optional user rate constant subroutine. The

user flag indicates the element number in this array which is used in a given rate

expression. When the user flag is not specified, or when the user rate constant routine

is not present, this parameter is set to 1.0.

138 8 Step-Growth Polymerization Model](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/aspenpolymersunitopsv82-usr-141128134016-conversion-gate02/85/Aspen-polymersunitopsv8-2-usr-150-320.jpg)

![Variable Usage Type Dimension Description

RCUSER Output REAL*8 NURC User rate constant vector (See User

Rate-Constant Subroutine, page 144)

CATWT Input REAL*8 Catalyst weight, kg (in RPLUG,

weight/length)

Example 3 illustrates how to use this subroutine to implement complex rate

expressions in the Step-Growth model.

Example 3: Implementing a Non-Ideal Rate Expression

Suppose a side reaction QZ is first order with respect to component Q and

first order with respect to a catalyst C. The effectiveness of the catalyst is

reduced by inhibitor I according to the following equation:

C

actual

1 ( )

C

eff a bT I

Where:

[C ] eff = Effective catalyst concentration, mol/L

[C ] actual = Actual catalyst concentration, mol/L

[I] = Inhibitor concentration, mol/L

T = Temperature, K

a,b = Equation parameters

The net rate expression can thus be written as:

C

a bT I

1 1

*

R T Tref

actual k e

rate Q

o

E

( )

[ ]

1

Where:

ko = Pre-exponential factor, (L/mol)/sec

E* = Activation energy

R = Gas law constant

Tref = Reference temperature for ko

[Q] = Concentration of component Q, mol/L

The standard rate expression for side reactions is:

E

R T T

1 1

*

rate k e ref C i

U j o

i

i

* ( )

Where:

= Product operator

Ci = Concentration of component i

8 Step-Growth Polymerization Model 147](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/aspenpolymersunitopsv82-usr-141128134016-conversion-gate02/85/Aspen-polymersunitopsv8-2-usr-159-320.jpg)

![i = Power-law exponent for component i

U = User rate constant

j = User rate-constant flag

Suppose the rate constant for the uninhibited reaction is 3 103 (L/mol)/min

at 150C, with an activation energy of 20 kcal/mol, and the inhibition rate

constants are A=0.20 L/mol, B=0.001 L/mol-K. The stoichiometric coefficients

and power-law exponents are specified directly in the Stoic and PowLaw-Exp

keywords. The Arrehnius rate parameters and reference temperature are also

specified directly in the model.

The parameters for the user rate constant equation can be specified using the

optional REALRC list. Including the parameters in the REALRC list allows the

model user to adjust these parameters using the standard variable accessing

tools, such as Sensitivity, Design-Specification, and Data-Regression.

The resulting model input is summarized below:

USER-VECS NREALRC=2 NUSERRC=1

REALRC VALUE-LIST=0.2D0 0.001D0

STOIC 1 Q -1.0 / Z 1.0

POWLAW-EXP 1 Q 1.0 / C 1.0

RATE-CON 1 3D-3<1/MIN> 20.000<kcal/mol>

TREF=150.0<C> URATECON=1

The power-law term from this equation is:

E

* 1 1

rate k e R T Tref

CQ o

Where:

[Q] = Concentration of component Q, mol/L

[C] = Catalyst concentration, mol/L

k= Pre-exponential factor

o Thus, the required user rate constant is:

1

U j

a bT I

( )

( ( )[ ]

1

1

Where:

[I] = Inhibitor concentration, mol/L

T = Temperature, K

a, b = Equation parameters

An excerpt from the user rate constant subroutine for this equation is shown

below:

C - Component Name -

INTEGER ID_IN(2)

DATA ID_IN /'INHI','BITO'/

148 8 Step-Growth Polymerization Model](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/aspenpolymersunitopsv82-usr-141128134016-conversion-gate02/85/Aspen-polymersunitopsv8-2-usr-160-320.jpg)

![C ======================================================================

C EXECUTABLE CODE

C ======================================================================

C - find location of inhibitor in the list of components -

DO 10 I = 1, NCOMP_NCC

IF ( IDSCC(1,I).EQ.ID_IN(1).AND.IDSCC(2,I).EQ.ID_IN(2) ) I_IN=I

10 CONTINUE

C - get the concentration of the inhibitor -

C_IN = 0.0D0

IF ( I_IN .GT.0 ) C_IN = CSS( I_IN )

C ----------------------------------------------------------------------

C Parameters: each REALR element defaults to zero if not specified

C ----------------------------------------------------------------------

A = 0.0D0

IF ( NREALR .GT. 0 ) A = REALR( 1 )

B = 0.0D0

IF ( NREALR .GT. 1 ) B = REALR( 2 )

C ----------------------------------------------------------------------

C User rate constant #1 U(1) = 1 / ( 1 + (A+BT)[I] )

C ----------------------------------------------------------------------

IF ( NURC.LT.1 ) GO TO 999

RCUSER(1) = 1.0D0 / ( 1.0D0 + ( A + B*TEMP ) * C_IN )

END IF

999 RETURN

User Kinetics Subroutine

The user kinetics subroutine is used to supplement the built-in kinetic

calculations. Use this subroutine when the side reaction kinetics are too

complicated to represent through the user rate constant routine, or when

previously written Fortran routines are to be interfaced to the Step-Growth

model.

The argument list for this subroutine is provided here. The argument list and

declarations are set up in a Fortran template called USRKIS.F, which is

delivered with Aspen Polymers.

User Subroutine Arguments

SUBROUTINE USRKIS(

1 SOUT, NSUBS, IDXSUB, ITYPE, XMW,

2 IDSCC, NPO, NBOPST, NIDS, IDS,

3 NINTB, INTB, NREALB, REALB,

4 NINTK, INTK, NREALK, REALK, NIWRK,

5 IWRK, NWRK, WRK, NCPMX, IDXM,

6 X, X1, X2, Y, DUMXS,

7 FLOWL, FLOWL1, FLOWL2, FLOWV, DUMFS,

8 VLQ, VLQ1, VLQ2, VVP, VOLSLT,

9 VLIQRX, VL1RX, VL2RX, VVAPRX, VSLTRX,

* IPOLY, NSEG, IDXSEG, NOLIG, IDXOLI,

1 NSGOLG, NGROUP, IDGRP, NSPEC, IDXSPC,

2 NFGSPC, CSS, CGROUP, TEMP, PRES,

3 RFLRTN, IFLRTN, CRATES, NTCAT, RATCAT,

4 NRC, PREEXP, ACTNRG, TEXP, TREF,

5 IUFLAG, NURC, RCUSER )

8 Step-Growth Polymerization Model 149](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/aspenpolymersunitopsv82-usr-141128134016-conversion-gate02/85/Aspen-polymersunitopsv8-2-usr-161-320.jpg)

![Symbol Description

f Initiator efficiency

[I] Initiator concentration in the aqueous phase (kmol/m3)

ka

Absorption constant for particles (s-1)

jcr Critical chain length

p

Volume fraction of polymer in polymer particle

kd

Initiator dissociation constant (s-1)

kde

Rate constant for the desorption of radicals from the

particles (m3/s)

kam

Rate constant for the absorption of radicals by micelles

(m/s)

kap

Rate constant for the absorption of radical by the particles

(m/s)

kp

Rate constant for propagation in particle phase (m3/kmol-s)

kpw

Rate constant for propagation in the aqueous phase

(m3/kmol-s)

kij Rate constant for activated initiation (m3/kmol-s)

act

kox

ij Rate constant for oxidation (m3/kmol-s)

kre

ij Rate constant for reduction (m3/kmol-s)

ktw

Rate constant for the termination in the aqueous phase

(m3/kmol-s)

pm Partition coefficient for the i-th component between polymer

Ki

particles and monomer droplets

Mp

Concentration of monomer in the polymer phase (kmol/m3)

Mwm

Molecular weight of monomer (kg/kmol)

Mw

Monomer concentration in aqueous phase (kmol/m3)

n Average number of radicals per particle

Np

Number of particles per unit volume of aqueous phase

(no./m3)

Na

Avogadro number

Nagg

Aggregation number

Nn

Number of particles containing n radicals per unit volume

(no./m3-s)

Rhomo

Rate of particle generation by homogeneous nucleation

(no./m3-s)

Rw

Radical concentration in the aqueous phase (kmol/m3)

RI

Rate of initiator dissociation (kmol/m3-s)

tnuc

Nucleation time(s)

v Volume of a single unswollen particle (m3)

10 Emulsion Polymerization Model 209](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/aspenpolymersunitopsv82-usr-141128134016-conversion-gate02/85/Aspen-polymersunitopsv8-2-usr-221-320.jpg)

![Symbol Description

vm

Volume of a single micelle (m3)

vh

Volume of a single particle formed by homogeneous

nucleation (m3)

v Volumetric growth rate of a single particle (m3/s)

vVolume of a swollen particle (m3)

s

vs Volumetric growth rate of a swollen particle (m3/s)

Rate of radical absorption by Np particles (Kmol/s)

Total rate of radical generation (Kmol/s- m3)

i

0

Zeroth moment of the particle size distribution (no./m3 of

aqueous phase)

1

First moment of the particle size distribution (m3/m3 of

aqueous phase)

2

Second moment of the particle size distribution (m6/m3 of

aqueous phase)

3

Third moment of the particle size distribution (m9/m3 of

aqueous phase)

Particles containing n radicals are produced by three kinetic events:

Absorption of a radical from the aqueous phase by a particle containing

(n-1) radical. The total rate of this event is given as:

N 1

p

nN

Radical desorption from a particle containing (n+1) radicals. The total rate

of this event is given as:

Nn+1 kde (n+1)

Termination in a particle containing (n+2) radicals. The total rate of this

reaction is given as:

[( 2)( 1)] 2 N k n n n tp

v

Particle Phase

Particles containing n free-radicals are depleted in the particle phase in three

analogous ways. By equating the rate of formation to the rate of depletion of

particles containing n free-radicals the recurrence formula is obtained:

/ ( 1)

N N N N k n N k n n

/ 1 ( 2)( 1) 1 1 2

n a p n de n tp N

210 10 Emulsion Polymerization Model

v

v

a

n a p de tp

a

N N N k n k n n

N

(3.12)

This recurrence formula was first developed by Smith and Ewart, in a slightly

modified form (Smith & Ewart, 1948). Equation 3.12 can be solved for the](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/aspenpolymersunitopsv82-usr-141128134016-conversion-gate02/85/Aspen-polymersunitopsv8-2-usr-222-320.jpg)

![In conventional emulsion polymerization where unimodal distributions are

normally encountered, the moments of the particle size distribution give

sufficient information about the nature of the particle size distribution. The

particle size distribution can be described in terms of different independent

variables such as diameter or volume of the particle. Since volumetric growth

rate of the particle in emulsion polymerization remains almost constant in

Stage I and Stage II of the process, the population balance equation is

formulated in terms of the volume of the particles.

General Population Balance Equation

The general population balance equation for the emulsion polymerization is

given as follows:

v , v F v

,

t

F t

t

k A N R R am m a w m h

v

v v v v

homo (3.15)

In Equation 3.15 the right-hand side represents the nucleation of particles

from miceller and homogeneous nucleation. Refer to the table on page 208

for an explanation of the variables used. The volumetric growth rate is v for

a single unswollen particle (Equation 3.5):

v

k M n

N

MW

d

p p

a

m

p

(3.16)

The general population balance equation can be converted to the equivalent

moment equations. The j-th moment of the particle size distribution is given

as:

( , )

0

jF j d

j

(3.17)

Applying moment definition in Equation 3.17 to the general population

balance equation in Equation 3.15, the first four moments of the particle size

distribution are given as:

d

dt

0 k A N [ R ] R am m a w

homo (3.18)

d

dt

v v k A N [ R ] v R (3.19)

0 m am m a w h

homo

1

d

dt

2v v2 k A N [ R ] v2 R m am m a w h

homo (3.20)

2

1

d

dt

3v v3 k A N [ R ] v3 R m am m a w h

homo (3.21)

3

2

Where:

kam = Kinetic constant for the absorption of the oligomeric

radicals into the micelles

Am = Area of the micelles

10 Emulsion Polymerization Model 217](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/aspenpolymersunitopsv82-usr-141128134016-conversion-gate02/85/Aspen-polymersunitopsv8-2-usr-229-320.jpg)

![Equation

b

Ea

1 1

i

k Catalyst k e T

i

Tref specified i

i

, [ ]

net i i o i U flag

T

ref

R T T

ref

Ea

i

Tunspecified * [ ] ref ,

i

k Catalyst i

e RT b

iU flag

net i i k o i T Assign User Rate Constants is used:

ratem

activitym C mj

k ,

aj

j i net i

ratem C k mj

,

aj

Assign User Rate Constants is not used: net m j

Nomenclature

Symbol Description

m User reaction number

i Rate constant set number

j Component number

Product operator

Cj

Concentration* of component j, mol/L

i

Catalyst order term for catalyst i (default = 1)

mj Power-law exponent for component j in reaction m

ko

Pre-exponential factor in user-specified inverse-time and concentration units**

net ,i k Net rate constant for set i assigned to reaction m

knet,m Net rate constant for reaction m

Ea Activation energy in user-specified mole-enthalpy units (default =0)

b Temperature exponent (default = 0)

R Universal gas constant in units consistent with the specified activation energy

T Temperature, K

Tref

Optional reference temperature. Units may be specified, they are converted to K in the

model. Defaults to global reference temperature (Global Tref) specified on the Specs sheet.

flag User flag for rate constant set i. This flag points to an element of the user rate constant

array.

U User rate constant vector calculated by the optional user rate constant subroutine. The user

flag indicates the element number in this array which is used in a given rate expression.

When the user flag is not specified, or when the user rate constant routine is not present,

this parameter is set to 1.0.

* The concentration basis may be changed to other units using the Concentration basis field on the

Specs sheet or using the optional concentration basis subroutine.

** The reference temperature may be specified globally on the Specs sheet or locally for each rate

constant set on the Rate-Constants sheet. If global and local reference temperatures are both

unspecified then this form of the equation is applied.

13 Segment-Based Reaction Model 271](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/aspenpolymersunitopsv82-usr-141128134016-conversion-gate02/85/Aspen-polymersunitopsv8-2-usr-283-320.jpg)

![[C ] eff = Effective catalyst concentration, mol/L

[C ] actual = Actual catalyst concentration, mol/L

[I] = Inhibitor concentration, mol/L

T = Temperature, K

a,b = Equation parameters

The net rate expression can thus be written as:

C

a bT I

1 1

*

R T Tref

actual k e

rate Q

o

E

( )

[ ]

1

Where:

ko = Pre-exponential factor, (L/mol)/sec

E* = Activation energy

R = Gas law constant

Tref = Reference temperature for ko

[Q] = Concentration of component Q, mol/L

The standard rate expression for side reactions is:

E

R T T

1 1

*

rate k e ref C i

U j o

i

i

* ( )

Where:

= Product operator

Ci = Concentration of component i

i = Power-law exponent for component i

U = User rate constant

j = User rate-constant flag

Suppose the rate constant for the uninhibited reaction is 3 103 (L/mol)/min

at 150C, with an activation energy of 20 kcal/mol, and the inhibition rate

constants are A=0.20 L/mol, B=0.001 L/mol-K. The stoichiometric coefficients

and power-law exponents are specified directly in the Stoic and PowLaw-Exp

keywords. The Arrehnius rate parameters and reference temperature are also

specified directly in the model.

The parameters for the user rate constant equation can be specified using the

optional REALRC list. Including the parameters in the REALRC list allows the

model user to adjust these parameters using the standard variable accessing

tools, such as Sensitivity, Design-Specification, and Data-Regression.

The resulting model input is summarized below:

USER-VECS NREALRC=2 NUSERRC=1

282 13 Segment-Based Reaction Model](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/aspenpolymersunitopsv82-usr-141128134016-conversion-gate02/85/Aspen-polymersunitopsv8-2-usr-294-320.jpg)

![REALRC VALUE-LIST=0.2D0 0.001D0

STOIC 1 Q -1.0 / Z 1.0

POWLAW-EXP 1 Q 1.0 / C 1.0

RATE-CON 1 3D-3<1/MIN> 20.000<kcal/mol>

TREF=150.0<C> URATECON=1

The power-law term from this equation is:

E

* 1 1

rate k e R T Tref

CQ o

Where:

[Q] = Concentration of component Q, mol/L

[C] = Catalyst concentration, mol/L

k= Pre-exponential factor

o Thus, the required user rate constant is:

1

U j

a bT I

( )

( ( )[ ]

1

1

Where:

[I] = Inhibitor concentration, mol/L

T = Temperature, K

a, b = Equation parameters

An excerpt from the user rate constant subroutine for this equation is shown

below:

C - Component Name -

INTEGER ID_IN(2)

DATA ID_IN /'INHI','BITO'/

C ======================================================================

C EXECUTABLE CODE

C ======================================================================

C - find location of inhibitor in the list of components -

DO 10 I = 1, NCOMP_NCC

IF ( IDSCC(1,I).EQ.ID_IN(1).AND.IDSCC(2,I).EQ.ID_IN(2) ) I_IN=I

10 CONTINUE

C - get the concentration of the inhibitor -

C_IN = 0.0D0

IF ( I_IN .GT.0 ) C_IN = CSS( I_IN )

C ----------------------------------------------------------------------

C Parameters: each REALR element defaults to zero if not specified

C ----------------------------------------------------------------------

A = 0.0D0

IF ( NREALR .GT. 0 ) A = REALR( 1 )

B = 0.0D0

IF ( NREALR .GT. 1 ) B = REALR( 2 )

C ----------------------------------------------------------------------

C User rate constant #1 U(1) = 1 / ( 1 + (A+BT)[I] )

C ----------------------------------------------------------------------

IF ( NURC.LT.1 ) GO TO 999

RCUSER(1) = 1.0D0 / ( 1.0D0 + ( A + B*TEMP ) * C_IN )

13 Segment-Based Reaction Model 283](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/aspenpolymersunitopsv82-usr-141128134016-conversion-gate02/85/Aspen-polymersunitopsv8-2-usr-295-320.jpg)

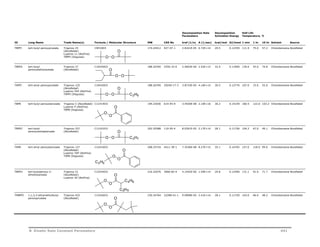

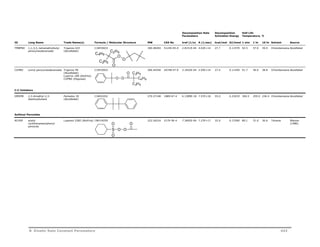

![Decomposition Rate

Parameters

Decomposition

Activation Energy

Half Life

Temperature, C

ID Long Name Trade Name(s) Formula / Molecular Structure MW CAS No kref (1/s) A (1/sec) kcal/mol GJ/kmol 1 min 1 hr 10 hr Solvent Source

Water Soluble Azo-Nitriles

ABAH 2,2’-azo-bis(2-

amidinopropane)

dihydrochloride

Vazo 56 (DuPont)

V-50 (Wako Chem)

C8H20N6Cl2 271.19264 2997-92-4 3.3436E-05 6.44E+14 29.4 0.12300 110.5 73.7 55.9 Water DuPont

VAZO68 4,4’-azo-bis

(4-cyanovaleric acid)

HCl NH HCl

HN

N N

H2N NH2

Vazo 68 (DuPont) C12H22N2O4 258.31776 2638-94-0 7.3642E-06 5.12E+12 27.2 0.11380 132.7 88.7 68.0 Water DuPont

VA61 2,2’-azo-bis[2-(2-

imidazolin-2-yl)propane]

N N

COOH

HOOC

VA-061 (Wako Chem) C12H22N6 250.34712 20858-12-2 1.3404E-03 1.00E+15 27.2 0.11400 78.4 45.0 28.9 Acidic water Wako

VA86 2,2’-Azobis[2-methyl-N-(2-

hydroxyethyl)propionamide]

N N

N

NH

N

HN

VA-086 C12H24N4O4 288.34712 61551-69-7 6.7869E-06 7.95E+14 30.6 0.12800 123.9 86.0 67.7 Water Wako

VAZO44 2,2’-azo-bis(N,N’-

dimethylene

isobutyramidine)

dihydrochloride

Vazo 44 (DuPont)

VA-44 (WakoChem)

O O

N N

HOH2CH2C NH HN CH2CH2OH

C12H24Cl2N6 323.26840 27776-21-2 1.3564E-04 8.10E+12 25.6 0.10700 103.3 63.0 44.0 Water DuPont

VA46B 2,2’-azo-bis[2-(2-

imidazolin-2-yl)propane

disulfate dihydrate

N N

N

NH

N

HN

2HCl

VA-046B (Wako Chem) C12H30N6O10S2 482.53664 20858-12-2 1.4388E-03 1.18E+17 30.4 0.12700 75.9 46.0 31.4 Water Wako

VA41 2,2’-azo-bis[2-(5-methyl-

2-imidazolin-2-yl)propane]

dihydrochloride

N N

N

NH

N H2SO4

HN

H2O

VA-041 (WakoChem) C14H26Cl2N6 349.30628 n/a 2.7035E-04 2.53E+15 28.9 0.12100 91.3 57.4 41.0 Water Wako

VA58 2,2’-azobis[2-(3,4,5,6-

tetrahydropyrimidin-2-

yl)propane] dihydrochloride

N N

N

NH

N

NH

HCl HCl

VA-058 (WakoChem) C14H28Cl2N6 351.32216 102834-39-0 2.5342E-05 1.44E+15 30.1 0.12600 111.8 75.5 58.0 Water Wako

VA57 2,2’-azobis[N-(2-

carboxyethyl)-2-

methylpropionamidine]

tetrahydrate

N N

NH

N N 2HCl

HN

VA-057 (WakoChem) C14H34N6O8 414.45960 n/a 2.8824E-05 5.56E+14 29.4 0.12300 112.0 74.9 57.0 Water Wako

HN

HN NH

HOOC COOH 4 H2O

N N

NH

434 B Kinetic Rate Constant Parameters](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/aspenpolymersunitopsv82-usr-141128134016-conversion-gate02/85/Aspen-polymersunitopsv8-2-usr-446-320.jpg)

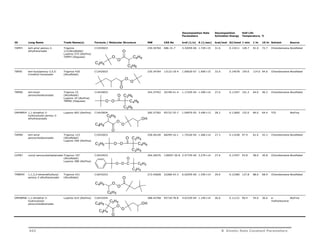

![Decomposition Rate

Parameters

Decomposition

Activation Energy

Half Life

Temperature, C

ID Long Name Trade Name(s) Formula / Molecular Structure MW CAS No kref (1/s) A (1/sec) kcal/mol GJ/kmol 1 min 1 hr 10 hr Solvent Source

VA85 2,2’-Azobis{2-methyl-N-[2-

(1-hydroxybuthyl)]

propionamide}

VA-085 (Wako Chem) C16H32N4O4 344.45464 n/a 7.8450E-07 6.41E+13 30.4 0.12700 148.2 105.4 85.0 Water Wako

VA60 2,2’-azo-bis{2-[1-(2-

hydroxyethyl)-2-imidazolin-

2-yl]propane}

dihydrochloride

O O

N N

NH HN

CH2CH3

H3CH2C

HOH2C CH2OH

VA-060 (Wako Chem) C16H32Cl2N6O2 411.37472 11858-13-0 1.9254E-05 9.56E+15 31.5 0.13200 111.7 76.9 60.0 Water Wako

Solvent Soluble Azo-Nitriles

N

N N

N N

N

2HCl

CH2CH2OH CH2CH2OH

V30 1-cyano-1-methyl-ethylazofomamide

V-30 (Wako Chem) C5H8N4O 140.14488 10288-28-5 4.4161E-08 1.86E+15 34.5 0.14430 164.9 123.9 104.0 Toluene Wako

AIBN 2,2'-azo-bis-isobutyronitrile Vazo 64 (DuPont)

Perkadox AIBN

(AkzoNobel)

CN

N N CONH2

C8H12N4 164.21024 78-67-1 1.0464E-05 2.74E+15 31.1 0.13023 118.3 82.0 64.4 Chlorobenzene AkzoNobel

AMBN 2,2'-azo-bis(2-

methylbutyronitrile)

Vazo 67 (DuPont)

Perkadox AMBN

(AkzoNobel)

V-59 (Wako Chem)

NC N N CN

C10H16N4 192.26400 13472-08-7 8.4357E-06 1.38E+15 30.8 0.12893 121.2 84.0 66.0 Chlorobenzene AkzoNobel

V601 dimethyl 2,2'-azobis (2-

methylpropionate)

C2H5

CN

N N

CN

C2H5

V-601 (Wako Chem) C10H18N2O4 230.26400 2589-57-3 8.5556E-06 6.99E+14 30.4 0.12700 122.1 84.3 66.0 Toluene Wako

ACCN 1,1-azo-di-(hexa

hydrobenzenenonitrile)

Vazo 88 (DuPont)

Perkadox ACCN

(AkzoNobel)

V-40 (Wako Chem)

O O

H3CO N N

OCH3

C14H20N4 244.33976 2094-98-6 5.4449E-07 1.07E+16 34.0 0.14219 140.2 103.0 84.9 Chlorobenzene AkzoNobel

AMVN 2,2'-azo-bis(2,4-dimethyl

valeronitrile)

Vazo 52 (DuPont)

V-65 (Wako Chem)

NC

N N

CN

C14H24N4 248.37152 4419-11-8 1.0349E-04 1.78E+14 27.8 0.11630 102.1 65.0 47.2 Toluene DuPont

VF096 2,2'-azo-bis[N-(2-

propenyl)-2-

methylpropionamide]

VF-096 (Wako Chem) C14H24N4O2 280.37032 129136-92-1 1.5480E-07 4.67E+14 32.7 0.13700 157.8 116.1 96.0 Toluene Wako

O O

N N

NH HN

B Kinetic Rate Constant Parameters 435](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/aspenpolymersunitopsv82-usr-141128134016-conversion-gate02/85/Aspen-polymersunitopsv8-2-usr-447-320.jpg)

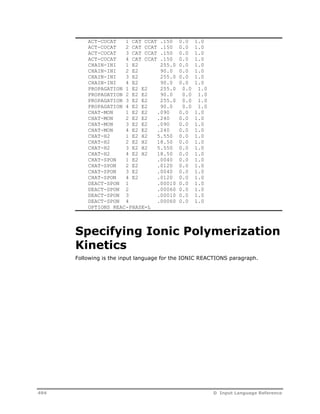

![D Input Language Reference

This section describes the input language for:

Specifying Components, 447

Specifying Component Attributes, 451

Specifying Attribute Scaling Factors, 453

Requesting Distribution Calculations, 454

Calculating End Use Properties, 454

Specifying Physical Property Inputs, 456

Specifying Step-Growth Polymerization Kinetics, 460

Specifying Free-Radical Polymerization Kinetics, 467

Specifying Emulsion Polymerization Kinetics, 477

Specifying Ziegler-Natta Polymerization Kinetics, 484

Specifying Ionic Polymerization Kinetics, 494

Specifying Segment-Based Polymer Modification Reactions, 501

Specifying Components

This section describes the input language for specifying components.

Naming Components

Following is the input language used to name components.

Input Language for Components

COMPONENTS cid [cname] [outid] / ...

Input Language Description for Components

COMPONENTS cid Component ID. Used to refer to the component in

all subsequent input and is also used to identify the

component in the simulation report. Aspen Plus

input language conventions and naming guidelines

apply to this keyword.

D Input Language Reference 447](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/aspenpolymersunitopsv82-usr-141128134016-conversion-gate02/85/Aspen-polymersunitopsv8-2-usr-459-320.jpg)

![userpropid User property set ID. This property must be different from

built-in properties. (See Aspen Physical Property System

Physical Property Data documentation.)

SUBROUTINE Name of user-supplied subroutine for calculating the

property. For details on writing the user-supplied subroutine,

see Aspen Plus User Models reference manual.

FLASH FLASH=NO Does not flash the stream before the

user-supplied subroutine is called

(Default)

FLASH=

NOCOMPOSITE

Does not flash the stream for total

stream properties (When PHASE=T in the

Prop-Set paragraph), but flashes for any

other phase specification

FLASH=YES Always flashes stream before the user-supplied

subroutine is called

UNIT-TYPE Units keyword for the property. If not entered, unit

conversion is not performed on property values returned from

the user-supplied subroutine.

UNIT-LABEL Unit label for the property printed in the report. A unit label is

used only when unit conversion is performed by the user-supplied

subroutine (that is, when UNIT-TYPE is not given).

COMP-DEP COMP-DEP=YES Property is component property

COMP-DEP=NO Property is a mixture property (Default)

Specifying Physical Property

Inputs

This section describes the input language for specifying physical property

inputs. More information on physical property methods and models is given in

Volume 2 of this User Guide.

Specifying Property Methods

Following is the input language used to specify property methods.

Input Language for Property Methods

PROPERTIES opsetname keyword=value /

opsetname [sectionid-list] keyword=value /...

Optional keywords:

FREE-WATER SOLU-WATER HENRY-COMPS

HENRY-COMPS henryid cid-list

456 D Input Language Reference](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/aspenpolymersunitopsv82-usr-141128134016-conversion-gate02/85/Aspen-polymersunitopsv8-2-usr-468-320.jpg)

![HENRY-COMPS HC INI1

PROPERTIES POLYNRTL HENRY-COMPS=HC

Specifying Property Data

Following is the input language used to specify property data.

Input Language for Property Data

PROP-DATA

PROP-LIST paramname [setno] / . . .

PVAL cid value-list / value-list / . . .

PROP-LIST paramname [setno] / . . .

BPVAL cid1 cid2 value-list / value-list / . . .

COMP-LIST cid-list

CVAL paramname setno 1 value-list

COMP-LIST cid2-list

BCVAL paramname setno 1 cid1 value-list /

1 cid1 value-list / . . .

Physical property models require data in order to calculate property values.

Once you have selected the property method(s) to be used in your simulation,

you must determine the parameter requirements for the models contained in

the property method(s), and ensure that they are available in the databanks.

If the model parameters are not available from the databanks, you may

estimate them using the Property Constant Estimation System, or enter them

using the PROP-DATA or TAB-POLY paragraphs. The input language for the

PROP-DATA paragraphs is as follows. Note that only the general structure is

given, for information on the format for the input parameters required by

polymer specific models see the relevant chapter in Volume 2 of this User

Guide.

Input Language Description for Property Data

PROP-LIST Used to enter parameter names and data set numbers.

PVAL Used to enter the PROP-LIST parameter values.

BPVAL Used to enter the PROP-LIST binary parameter values.

COMP-LIST Used to enter component IDs.

CVAL Used to enter the COMP-LIST parameter values.

BCVAL Used to enter the COMP-LIST binary parameter values.

paramname Parameter name

458 D Input Language Reference](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/aspenpolymersunitopsv82-usr-141128134016-conversion-gate02/85/Aspen-polymersunitopsv8-2-usr-470-320.jpg)

![Input Language for Property Parameter Estimation

ESTIMATE [option]

STRUCTURES

method SEG-id groupno nooccur / groupno nooccur /...

Input Language Description for Property Parameter Estimation

The main keywords for specifying property parameter estimation inputs are

the ESTIMATE and the STRUCTURES paragraphs. A brief description of the

input language for these paragraphs follows. For more detailed information

please refer to the Aspen Physical Property System Physical Property Data

documentation.

option Option=ALL Estimate all missing parameters (default)

method Polymer property estimation method name

SEG-id Segment ID defined in the component list

groupno Functional group number (group IDs listed in Appendix B of

Volume 2 of this User Guide)

nooccur Number of occurrences of the group

Input Language Example for Property Parameter Estimation

ESTIMATE ALL

STRUCTURES

VANKREV ABSEG 115 1 ;-(C6H4)-

VANKREV BSEG 151 2 / 100 2 ; -COO-CH2-CH2-COO-VANKREV

ABSEG 115 1 / 151 2 / 100 2 ;-(C6H4)-COO-CH2-CH2-COO-Specifying

Step-Growth

Polymerization Kinetics

Following is the input language for the STEP-GROWTH REACTIONS paragraph.

Input Language for Step-Growth Polymerization

REACTIONS rxnid STEP-GROWTH

DESCRIPTION '...'

REPORT REPORT=yes/no RXN-SUMMARY=yes/no RXN-DETAILS=yes/noI

STOIC reactionno compid coeff / ...

RATE-CON setno pre-exp act-energy [T-exp] [T-ref] [USER-RC=number]

[CATALYST=compid] [CAT-ORDER=value]

POWLAW-EXP reactionno compid exponent /

[ASSIGN reactionno [ACTIVITY=value] RC-SETS=setno-list]

SPECIES POLYMER=polymerid OLIGOMER=oligomer-list

REAC-GRP groupid type /...

SPEC-GROUP compid groupid number / groupid number / ...

460 D Input Language Reference](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/aspenpolymersunitopsv82-usr-141128134016-conversion-gate02/85/Aspen-polymersunitopsv8-2-usr-472-320.jpg)

![RXN-SET rxn-setno

[A-NUCL-SPEC=compid] [A-ELEC-GRP=groupid] &

[V-ELEC-SPEC=compid] [V-NUCL-GRP=groupid] &

[V-NUCL-SPEC=compid] [V-ELEC-GRP=groupid] &

RC-SETS=rc-setno-list

SG-RATE-CON rc-setno

[CAT-SPEC=compid] [CAT-GRP=groupid] &

sgpre-exp [sgact-energy] [sgt-exp] [sgt-ref] [USER-RC=number]

SUBROUTINE KINETICS=kinname RATECON=rcname MASSTRANS=mtname

USER-VECS NINTK=nintk NREALK=nrealk NINTRC=nintrc &

NREALRC=nrealc NINTMT=nintmt NREALMT=nrealmt &

NIWORK=niwork NWORK=nwork NURC=nurc

INTK value-list

REALK value-list

INTRC value-list

REALRC value-list

INTMT value-list

REALMT value-list

INCL-COMPS compid-list

REAC-TYPE FOR-CON=yes/no REV-CON=yes/no REARRANGE=yes/no

EXCHANGE=yes/no

CONVERGENCE SOLVE-ZMOM=yes/no OLIG-TOL=tolerance

OPTIONS REAC-PHASE=phaseid CONC-BASIS=basis SUPPRESS-WARN=yes/no

USE-BULK=yes/no

The keywords for specifying rate constant parameters for the built-in

reactions, and for specifying user reactions are described here.

Input Language Description for Step-Growth Polymerization

rxnid Unique paragraph ID.

DESCRIPTION Up to 64 characters between double quotes.

REPORT Reaction report options- controls writing of reaction report

in .REP file.

REPORT=YES Print reaction report

REPORT=NO Do not print reaction report

RXN-SUMMARY=

YES

Print stoichiometry for each model-generated

and user-specified reaction.

(Default).

RXN-SUMMARY=

NO

Do not print this summary.

RXN-DETAILS=YES Print stoichiometry, rate constants, and

probability factors for each model-generated

and user-specified reaction.

RXN-DETAILS=NO Do not print this detailed summary.

STOIC Used to specify stoichiometry for user reactions.

Reactionno Reaction number

compid Component ID

D Input Language Reference 461](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/aspenpolymersunitopsv82-usr-141128134016-conversion-gate02/85/Aspen-polymersunitopsv8-2-usr-473-320.jpg)

![Input Language for Free-Radical Polymerization

REACTIONS reacid FREE-RAD

PARAM QSSA=yes/no QSSAZ=yes/no QSSAF=yes/no RAD-INTENS=value

SPECIES POLYMER=cid INITIATOR=cid-list MONOMER=cid-list INHIBITOR=cid-list &

SOLVENT=cid-list BI-INITIATOR=cid-list COINITIATOR=cid-list CHAINTAG=cid-list &

CATALYST=cid-list INIT-DEC cid idpre-exp idact-energy idact-volume ideffic &

idnrad ref-temp [GEL-EFFECT=gelid] [EFF-GEFF=gelid] [COEF1=value BYPROD1=cid] &

[COEF2=value BYPROD2=cid]

INIT-CAT cid1 cid2 icpre-exp icact-energy icact-volume iceffic

icnrad ref-temp [GEL-EFFECT=gelid] [EFF-GEFF=gelid] &

[COEF1=value BYPROD1=cid] [COEF2=value BYPROD2=cid]

INIT-SP cid1 cid2 ispre-exp isact-energy isact-volume ref-temp &

[GEL-EFFECT=gelid] [COEF1=value BYPROD1=cid] [COEF2=value BYPROD2=cid]

INIT-SP-EFF cid coeffa coeffb coeffc

BI-INIT-DEC cid bdpre-exp bdact-energy bdact-volume bdeffic

ref-temp [GEL-EFFECT=gelid] [EFF-GEFF=gelid] &

[COEF1=value BYPROD1=cid] [COEF2=value BYPROD2=cid]

SEC-INIT-DEC cid sdpre-exp sdact-energy sdact-volume sdeffic

ref-temp [GEL-EFFECT=gelid] [EFF-GEFF=gelid] &

[COEF1=value BYPROD1=cid] [COEF2=value BYPROD2=cid]

CHAIN-INI cid cipre-exp ciact-energy ciact-volume ref-temp [GEL-EFFECT=gelid]

PROPAGATION cid1 cid2 prpre-exp pract-energy pract-volume ref-temp [GEL-EFFECT=gelid]

CHAT-MON cid1 cid2 cmpre-exp cmact-energy cmact-volume ref-temp [GEL-EFFECT=gelid]

CHAT-POL cid1 cid2 cppre-exp cpact-energy cpact-volume ref-temp [GEL-EFFECT=gelid]

CHAT-AGENT cid1 cid2 capre-exp caact-energy caact-volume ref-temp [GEL-EFFECT=gelid]

CHAT-SOL cid1 cid2 cspre-exp csact-energy csact-volume ref-temp [GEL-EFFECT=gelid]

B-SCISSION cid bspre-exp bsact-energy bsact-volume ref-temp [GEL-EFFECT=gelid]

TERM-DIS cid1 cid2 tdpre-exp tdact-energy tdact-volume ref-temp [GEL-EFFECT=gelid]

TERM-COMB cid1 cid2 tcpre-exp tcact-energy tcact-volume ref-temp [GEL-EFFECT=gelid]

INHIBITION cid1 cid2 inpre-exp inact-energy inact-volume ref-temp [GEL-EFFECT=gelid]

SC-BRANCH cid1 cid2 scpre-exp scact-energy scact-volume ref-temp [GEL-EFFECT=gelid]

HTH-PROP cid1 cid2 hppre-exp hpact-energy hpact-volume ref-temp [GEL-EFFECT=gelid]

CIS-PROP cid1 cid2 pcpre-exp pcact-energy pcact-volume ref-temp [GEL-EFFECT=gelid]

TRANS-PROP cid1 cid2 ptpre-exp ptact-energy pcact-volume ref-temp [GEL-EFFECT=gelid]

TDB-POLY cid1 cid2 tdpre-exp tdact-energy tdact-volume ref-temp [GEL-EFFECT=gelid]

PDB-POLY cid1 cid2 pbpre-exp pbact-energy pbact-volume ref-temp [GEL-EFFECT=gelid]

GEL-EFFECT gelid CORR-NO=corrno &

MAX-PARAMS=maxparams GE-PARAMS=paramlist / ...

SUBROUTINE GEL-EFFECT=subname

OPTIONS REAC-PHASE=phaseid SUPRESS-WARN=yes/no USE-BULK=yes/no

Input Language Description for Free-Radical Polymerization

reacid Paragraph ID.

PARAM Used to specify polymerization mechanism, radiation

intensity, and request the Quasi-Steady-State

Approximation (QSSA).

RAD-INTENS=

value

Used to specify a value for the radiation

intensity to be used for the induced

initiation reaction (default is 1.0)

QSSA=

YES/NO

Used to request QSSA for all moments

(default is NO)

468 D Input Language Reference](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/aspenpolymersunitopsv82-usr-141128134016-conversion-gate02/85/Aspen-polymersunitopsv8-2-usr-480-320.jpg)

![Input Language for Emulsion Polymerization

REACTIONS reacid EMULSION

PARAM KBASIS=monomer/aqueous

SPLIT-PM spm-cid kll

SPECIES INITIATOR=cid MONOMER=cid INHIBITOR=cid &

DISPERSANT=cid . . .

INIT-DEC phasid cid idpre-exp idact-energy [idact-volume] ideffic &

idnrad ref-temp

INIT-CAT phased cid1 cid2 icpre-exp icact-energy [icact-volume] iceffic &

icnrad ref-temp

INIT-ACT phasid cid1 cid2 iapre-exp iaact-energy [iaact-volume] iaeffic &

ianrad ref-temp

PROPAGATION phasid cid1 cid2 prpre-exp pract-energy [pract-volume] ref-temp

CHAT-MON phasid cid1 cid2 cmpre-exp cmact-energy [cmact-volume] ref-temp

CHAT-POL phasid cid1 cid2 cppre-exp cpact-energy [cpact-volume] ref-temp

CHAT-AGENT phasid cid1 cid2 capre-exp caact-energy [caact-volume] ref-temp

TERM-DIS phasid cid1 cid2 tdpre-exp tdact-energy [tdact-volume] ref-temp

TERM-COMB phasid cid1 cid2 tcpre-exp tcact-energy [tcact-volume] ref-temp

INHIBITION phasid cid1 cid2 inpre-exp inact-energy [inact-volume] ref-temp

REDUCTION phasid cid1 cid2 rdpre-exp rdact-energy [rdact-volume] rdeffic &

rdnrad ref-temp

OXIDATION phasid cid1 cid2 oxpre-exp oxact-energy [oxact-volume] ref-temp

GEL-EFFECT GETYPE=reactiontype CORR-NO=corrno &

MAX-PARAMS=maxparams GE-PARAMS=paramlist / ...

SUBROUTINE GEL-EFFECT=subname

ABS-MIC ampre-exp amact-energy

ABS-PART appre-exp apact-energy

DES-PART dppre-exp dpact-energy

EMUL-PARAMS emulid cmc-conc area

Input Language Description for Emulsion Polymerization

reacid Paragraph ID.

PARAM Use to enter basis parameters.

KBASIS=

monomer/

aqueous

Basis for phase split ratios

SPLIT-PM Used to enter homosaturation solubility of species in the

polymer phase.

spm-cid Component ID of the species

partitioning into the polymer phase

kll Ratio of mass fraction of species in

polymer phase to mass fraction in

reference phase. KBASIS determines

whether the reference phase is the

monomer of aqueous phase

SPECIES Reacting species identification. This sentence is used to

associate components in the simulation with species in the

built-in free-radical kinetic scheme. The following species

keywords are currently valid

INITIATOR CATALYST MONOMER

CHAINTAG DISPERSANT INHIBITOR

POLYMER EMULSIFIER ACTIVATOR

REDOX-AGENT REDUCTANT

478 D Input Language Reference](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/aspenpolymersunitopsv82-usr-141128134016-conversion-gate02/85/Aspen-polymersunitopsv8-2-usr-490-320.jpg)

![OPTIONS Specify reaction model options.

REAC-PHASE=

phaseid

Specify the reacting phase as L, L1, L2, or V

(default is L)

SUPRESS-WARN=

yes/no

YES: do not print warnings when the

specified phase is not present

NO: always print warnings when the

specified phase is not present (default)

USE-BULK=

yes/no

YES: force the model to apply the specified

reaction kinetics to the bulk phase when the

specified phase is not present (default)

NO: rates are set to zero when the specified

phase is not present

Input Language Example for Ionic Polymerization

REACTIONS rxnid SEGMENT-BAS

DESCRIPTION '...'

PARAM TREF=value PHASE=V/L/L1/L2 SOLVE-ZMOM=YES/NO &

[SUPRESS-WARN=yes/no] [USE-BULK=yes/no] CBASIS=basis &

[REAC-SITE=siteno S-BASIS=basis]

SPECIES POLYMER=polymerid

STOIC reactionno compid coef / ...

RATE-CON reactionno pre-exp act-energy [t-exp] [TREF=ref-temp] &

[CATALYST=cid CAT-ORDER=value] [USER-RC=userid] / ...

POWLAW-EXP reactionno compid exponent /

[ASSIGN reactionno [ACTIVITY=value] RC-SETS=setno-list]

SUBROUTINE RATECON=rcname MASSTRANS=mtname

USER-VECS NINTRC=nintrc NREALRC=nrealc NINTMT=nintmt NREALMT=nrealmt &

NIWORKRC=niwork NWORKRC=nwork NIWORKMT=niwork NWORKMT=nwork &

NURC=nurc

INTRC value-list

REALRC value-list

INTMT value-list

REALMT value-list

Specifying Segment-Based

Polymer Modification Reactions

The input language for the SEGMENT-BAS REACTIONS paragraph is described

here.

Input Language for Segment-Based Polymer Modification Reactions

D Input Language Reference 501](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/aspenpolymersunitopsv82-usr-141128134016-conversion-gate02/85/Aspen-polymersunitopsv8-2-usr-513-320.jpg)

![REACTIONS rxnid SEGMENT-BAS

DESCRIPTION '...'

PARAM T-REFERENCE=value PHASE=V/L/L1/L2 CBASIS=basis &

SOLVE-ZMOM=YES/NO SPECIES POLYMER=polymerid

STOIC reactionno compid coef / ...

RATE-CON reactionno pre-exp act-energy [t-exp] / ...

POWLAW-EXP reactionno compid exponent /

The keywords for specifying rate constant parameters, reaction stoichiometry,

and reacting polymer are described here.

Input Language Description for Segment-Based Polymer Modification

Reactions

reacid Unique paragraph ID.

DESCRIPTION Up to 64 characters between double quotes.

PARAM Used to enter reaction specifications.

T-REF=

value

Reference temperature. If no reference

temperature is given, the term 1/Tref is

dropped from the rate expression:

rate C k e j j oi

Ea

i

1 1

ij R T T

ref

For more information, see the Segment-

Based Reaction Model section in Chapter 3.

PHASE=V/L/L1

/L2

Reacting phase

CBASIS Basis for power law rate expression. Choices

are:

MOLARITY

MOLALITY

MOLEFRAC

MASSFRAC

MASSCONC

SUPRESS-WARN=

yes/no

YES: do not print warnings when the

specified phase is not present

NO: always print warnings when the

specified phase is not present (default)

USE-BULK=

yes/no

YES: force the model to apply the specified

reaction kinetics to the bulk phase when the

specified phase is not present (default)

NO: rates are set to zero when the specified

phase is not present

SOLVE-ZMOM=

Option to explicitly solve for zeroth moment

based on segment types (default=no)

502 D Input Language Reference](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/aspenpolymersunitopsv82-usr-141128134016-conversion-gate02/85/Aspen-polymersunitopsv8-2-usr-514-320.jpg)