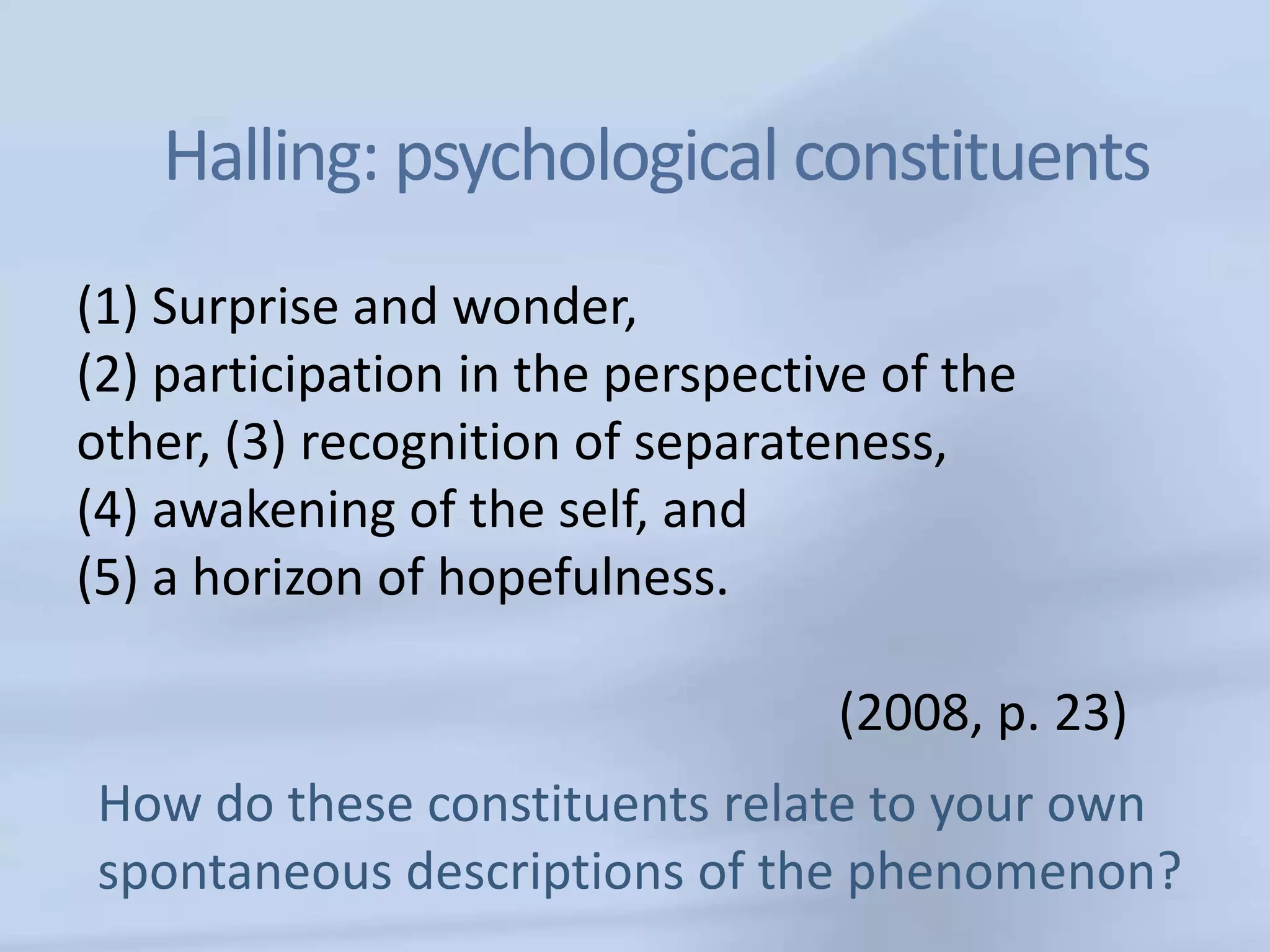

This document outlines a seminar on descriptive phenomenological psychology, emphasizing its roots in the philosophies of Edmund Husserl and Maurice Merleau-Ponty. It discusses the importance of understanding human experience beyond natural science, introducing the phenomenological method and its application in research about intimacy, resilience, and empathy. The document also highlights examples of psychological research and the complexities of human experiences, advocating for a deeper exploration of lived meanings.