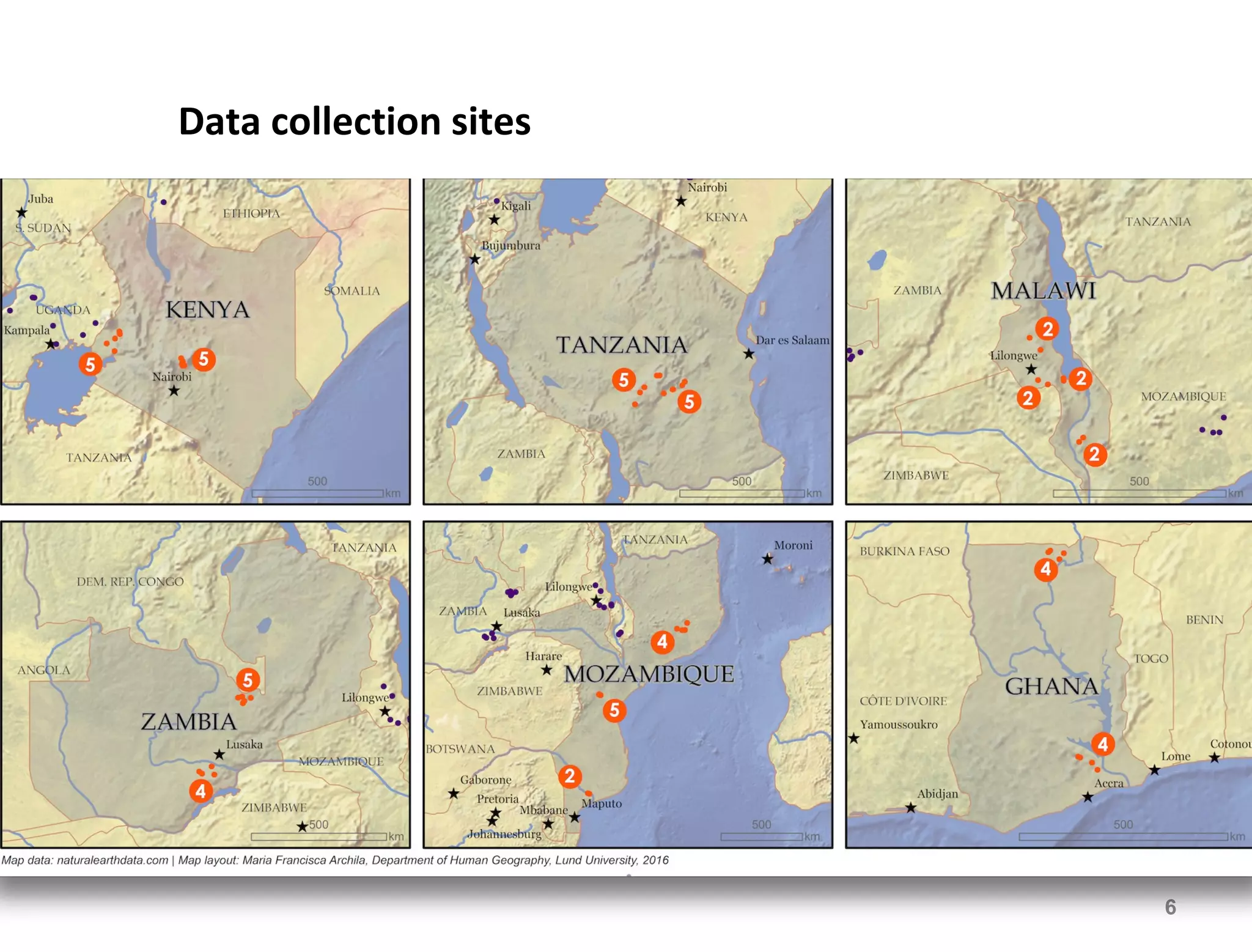

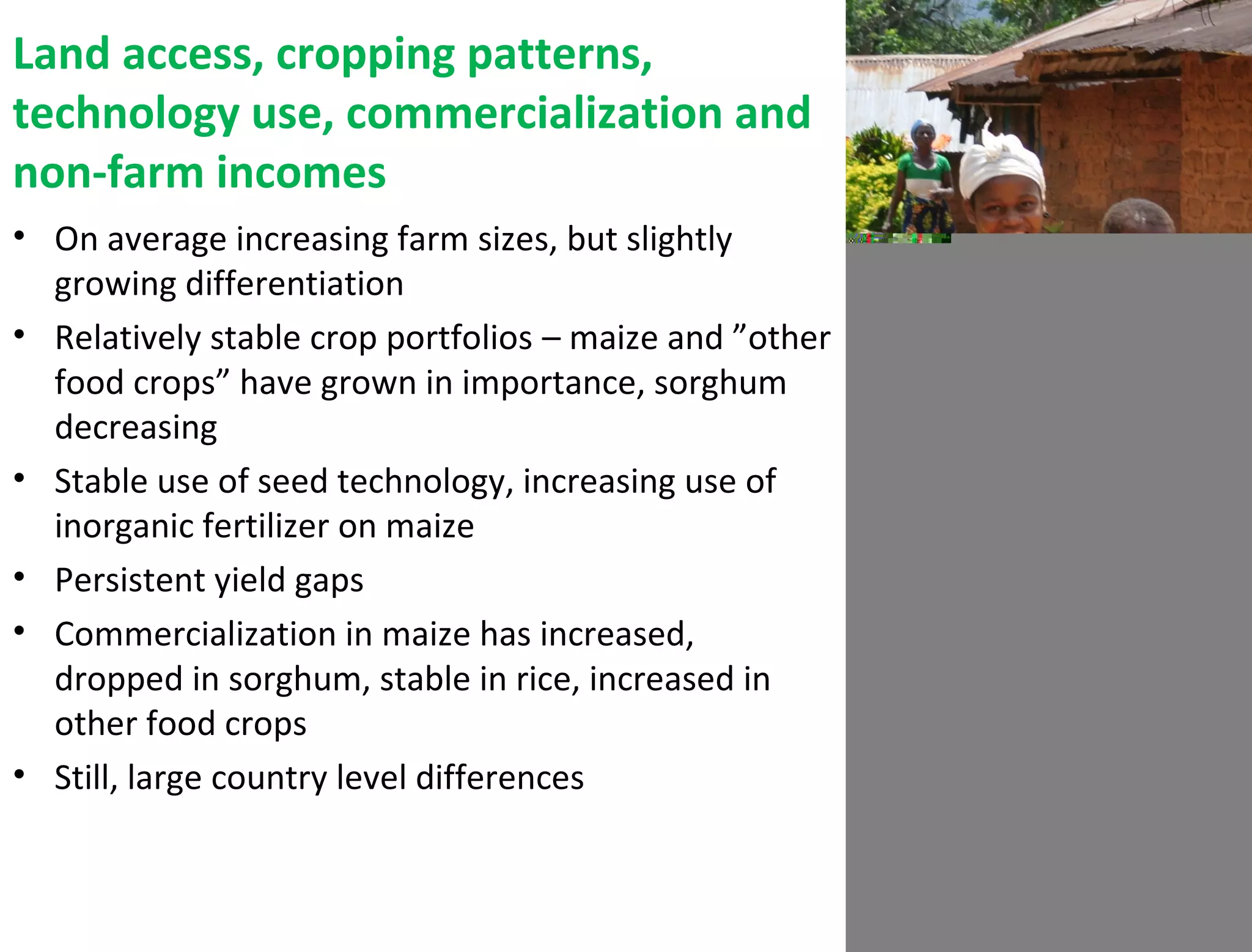

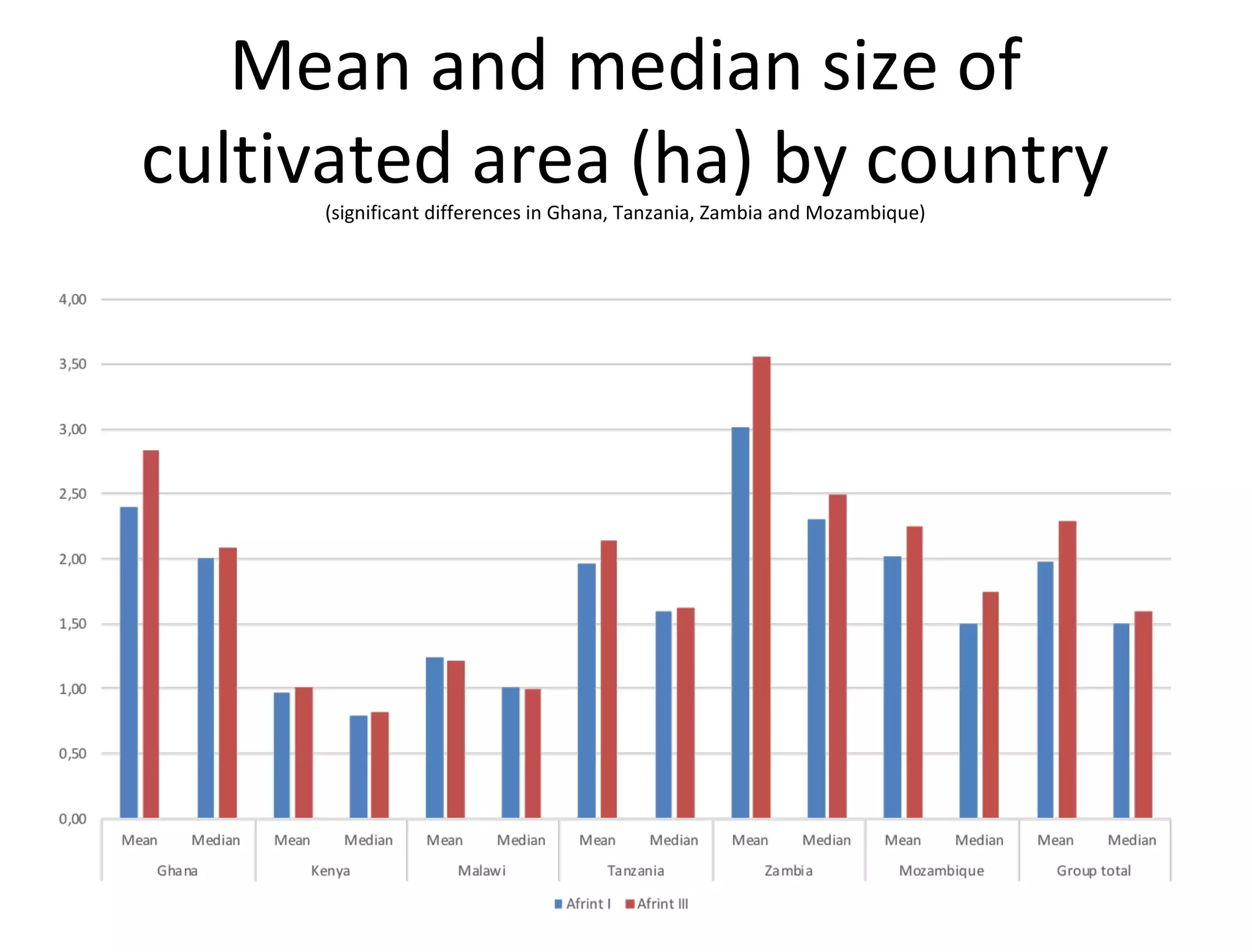

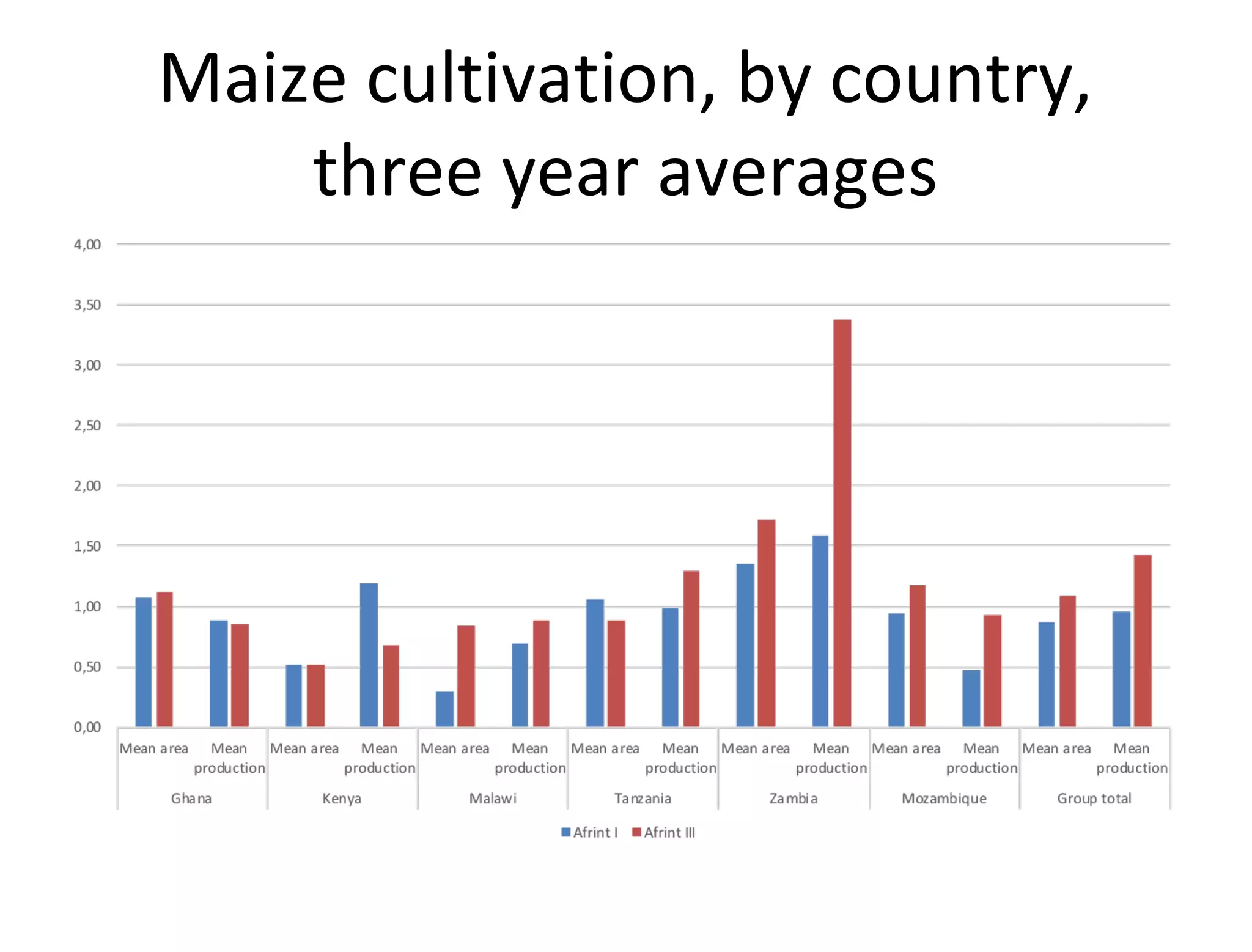

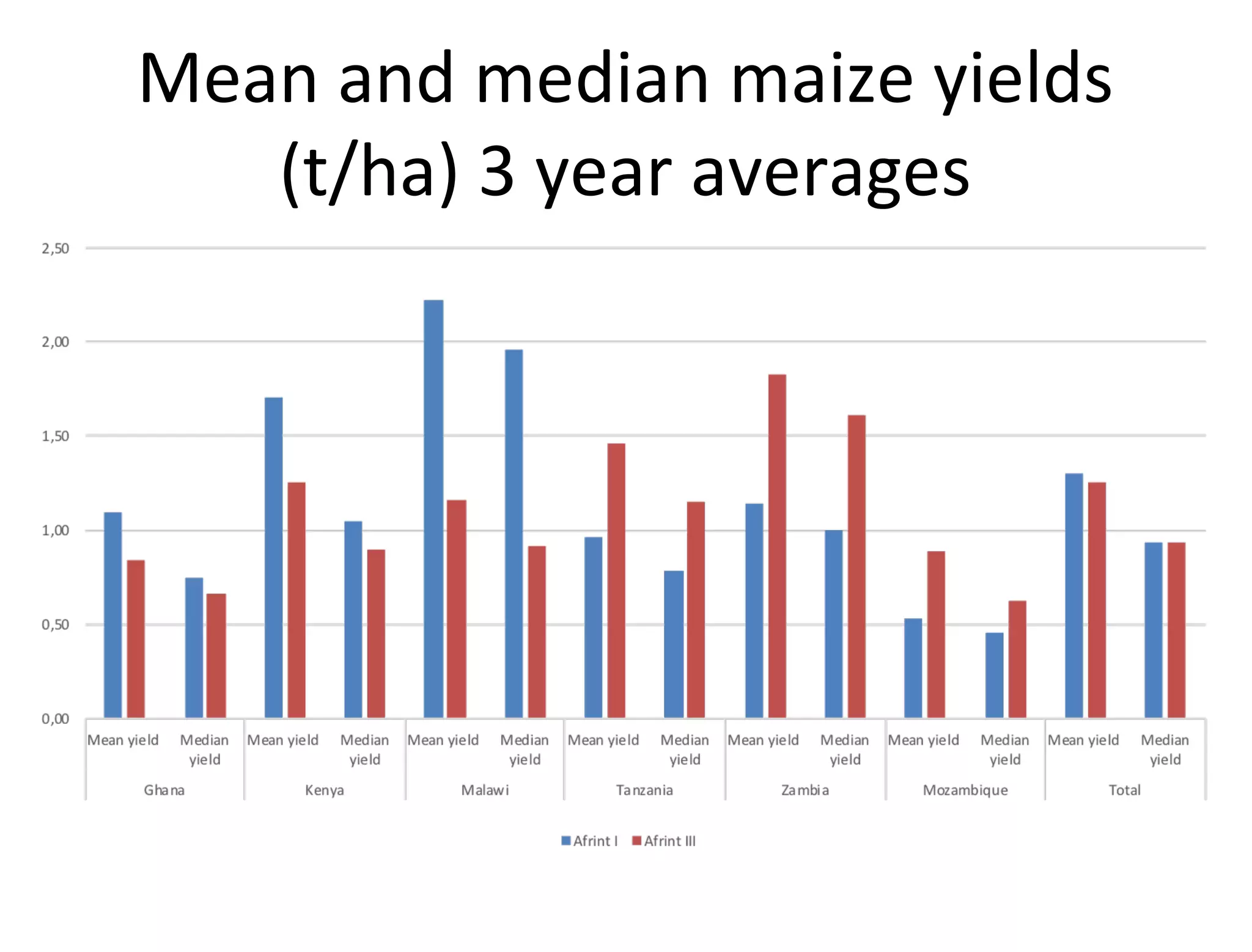

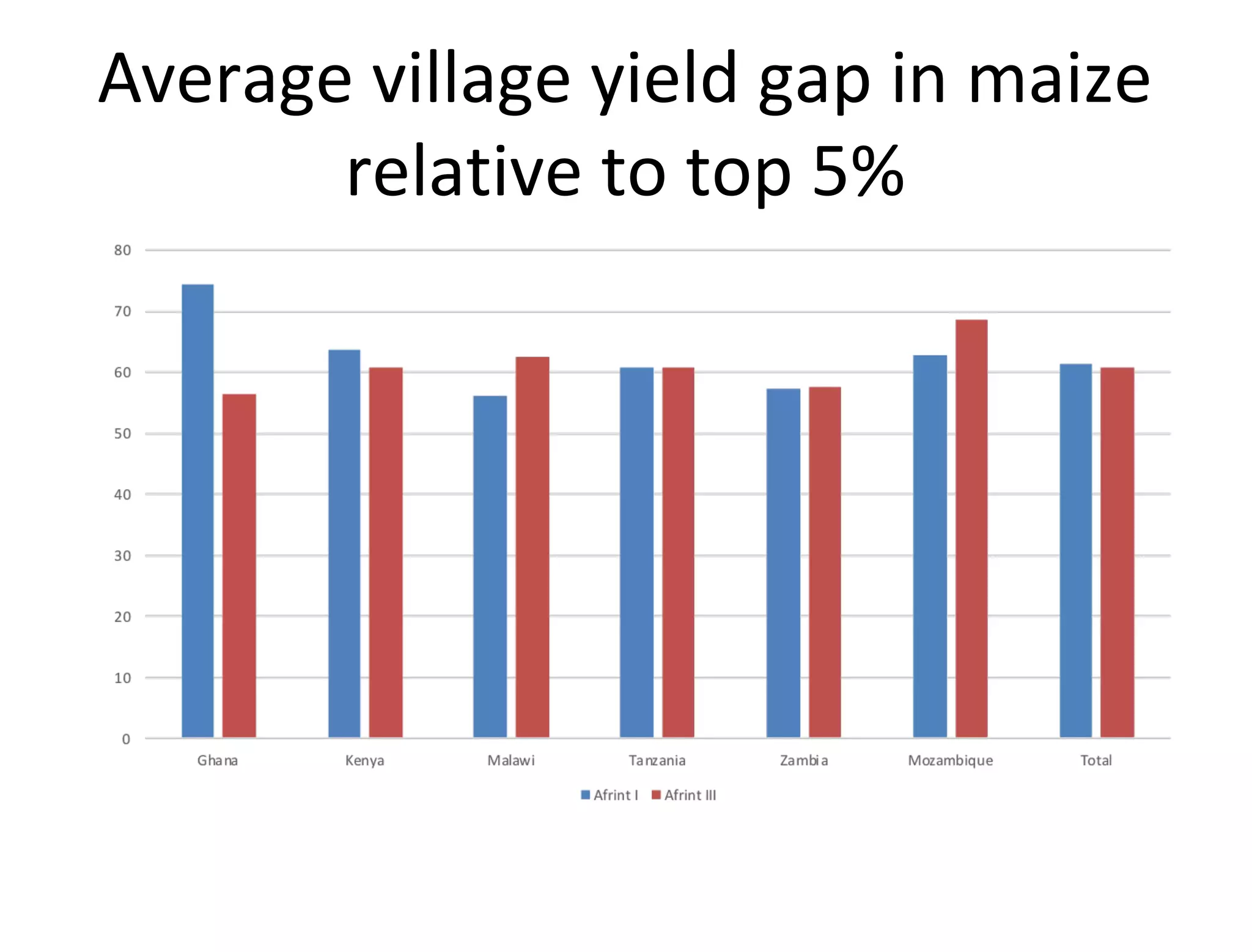

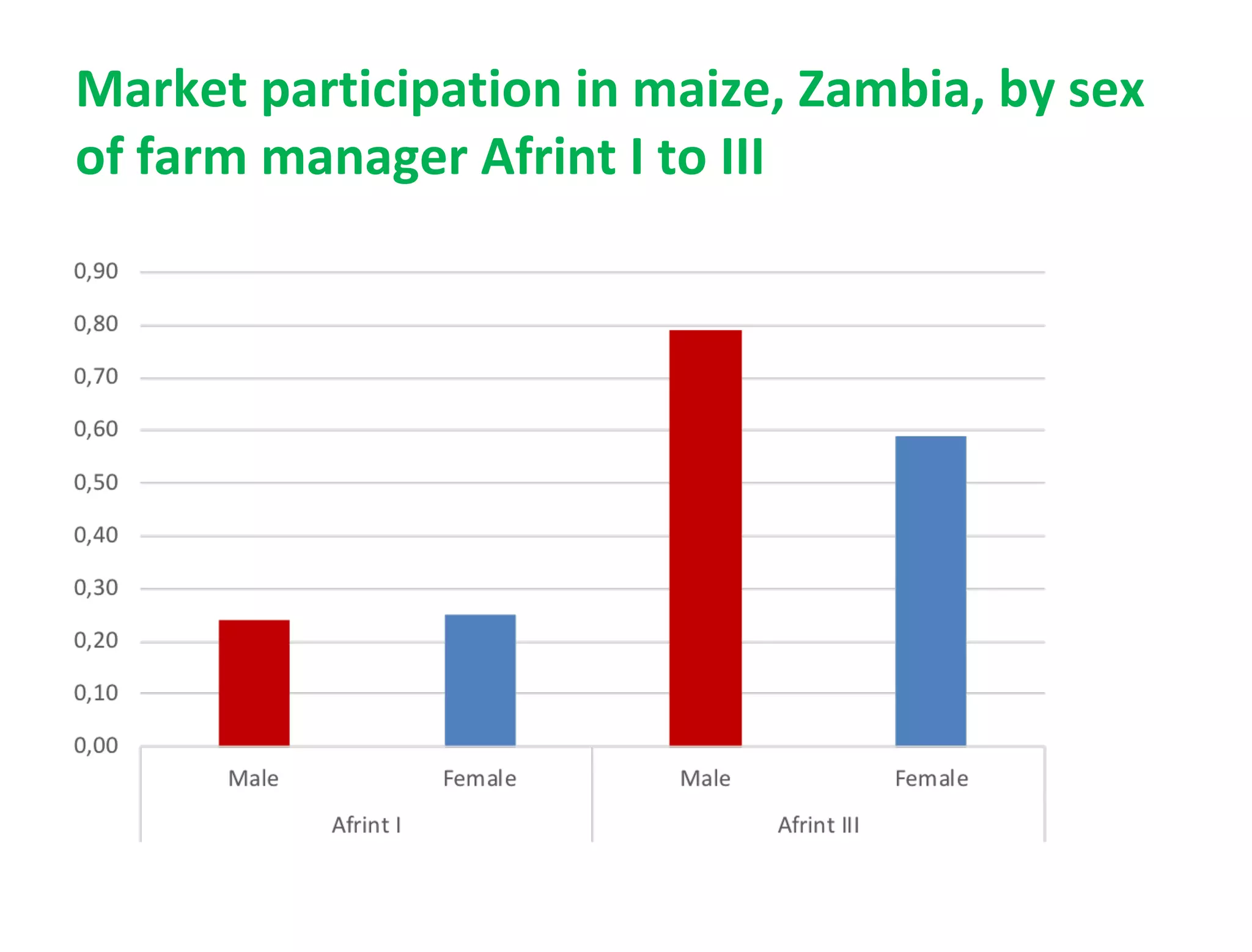

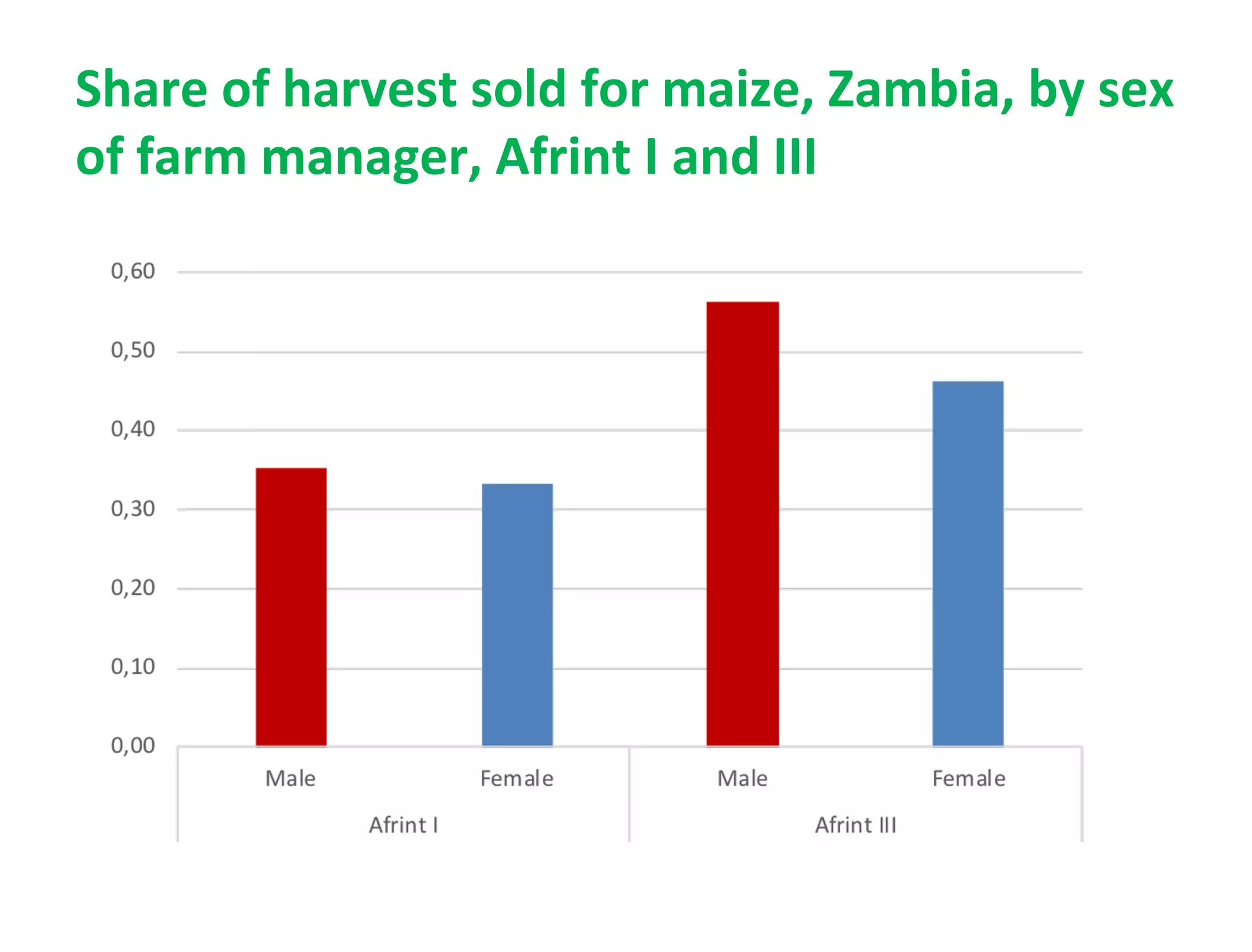

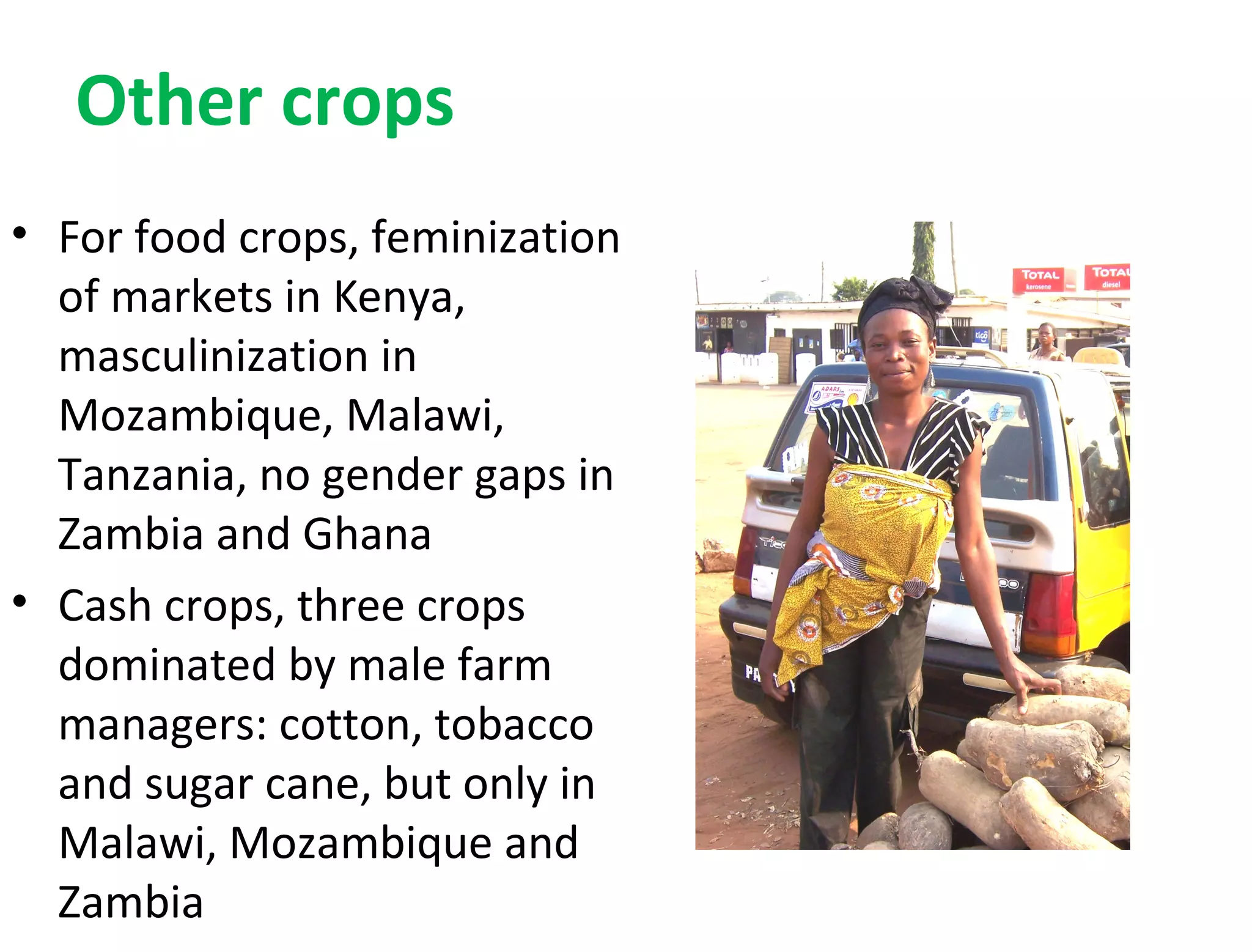

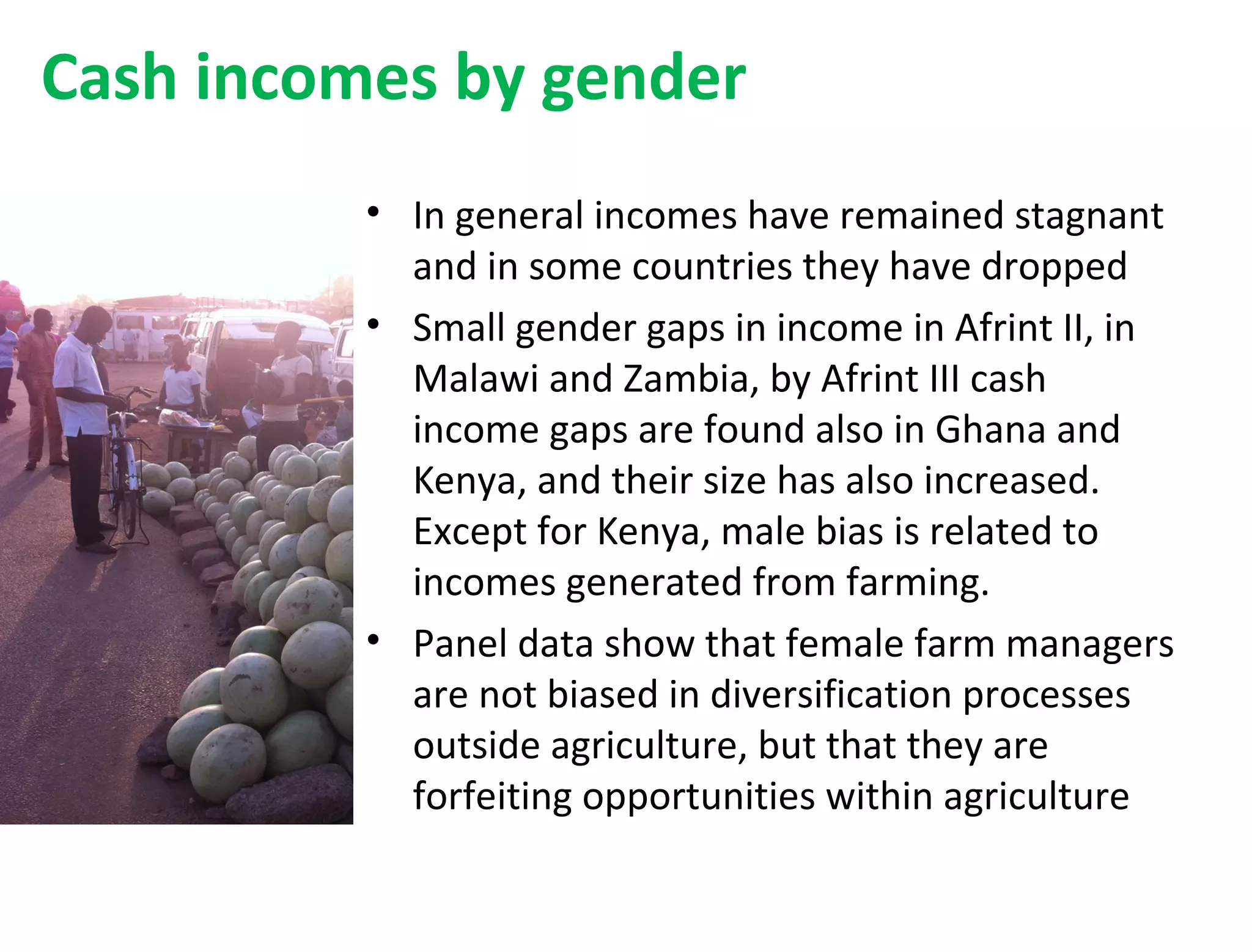

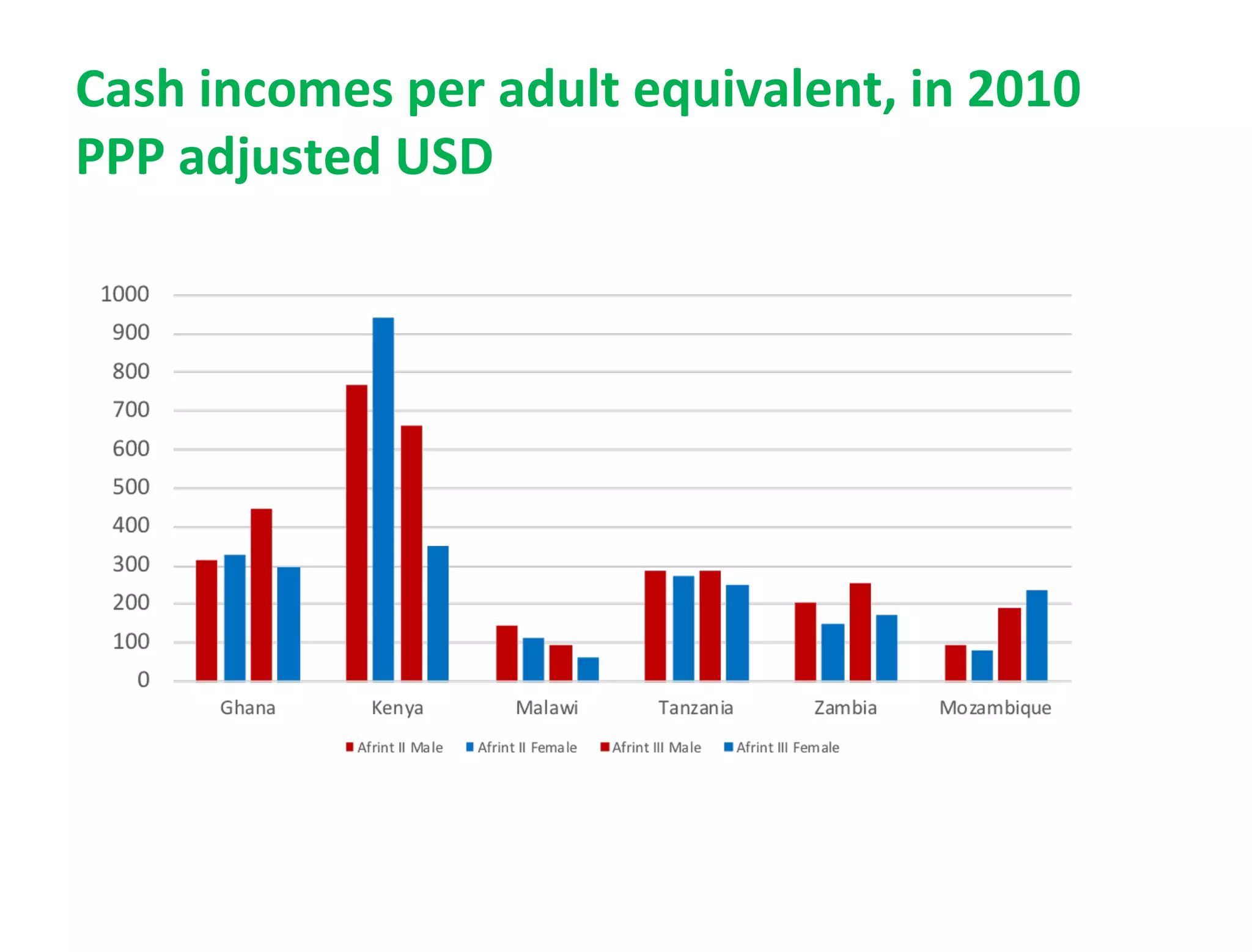

The document analyzes broader African agricultural trends from 2002 to 2013, highlighting issues such as rapid economic growth, urbanization, poverty contrasts, and gender discrimination in agrarian sectors. It emphasizes changes in smallholder dynamics, including land access, crop technology, gender disparities in income and asset access, and the growing significance of non-farm incomes. Overall, it suggests that while some farms have expanded, disparities persist, particularly along gender lines, with persistent yield gaps and varied commercialization outcomes across different countries.