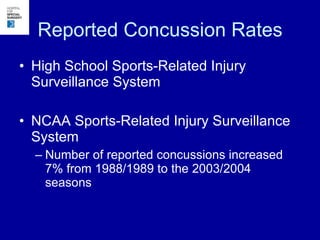

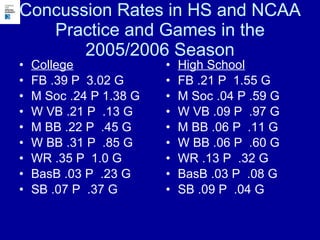

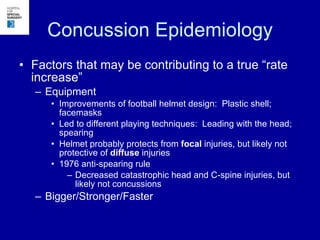

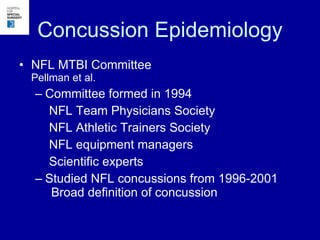

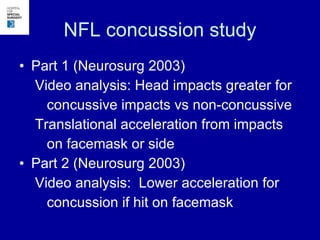

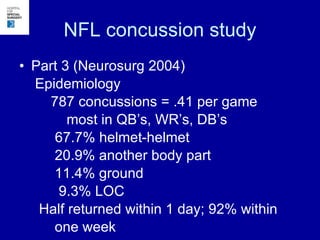

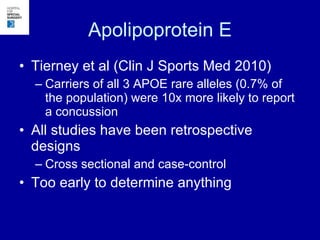

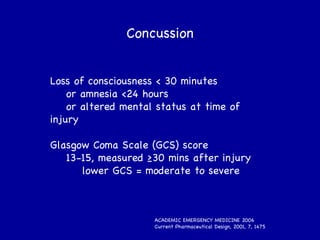

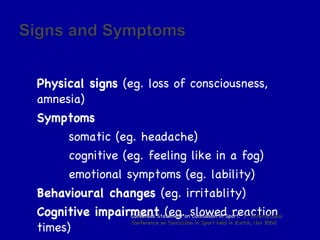

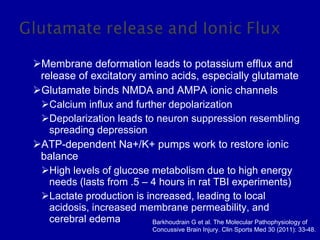

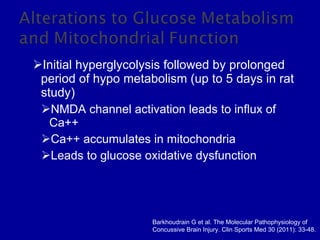

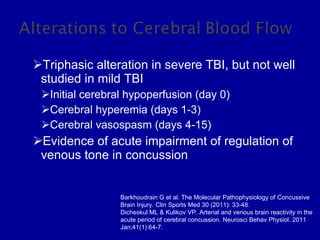

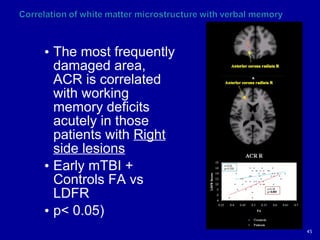

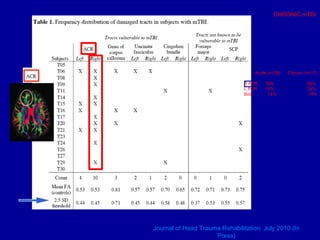

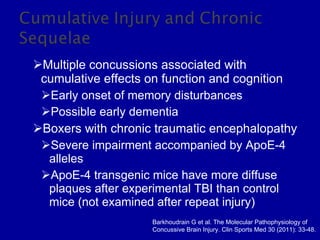

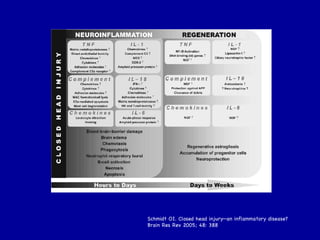

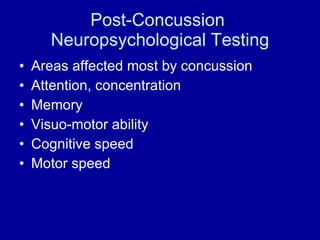

The document discusses concussion epidemiology and pathophysiology. It notes that concussions are underreported and their true effects are not fully understood. While their pathology is unclear, concussions involve biochemical and structural changes in the brain like glutamate release, altered blood flow, and axonal injury that can persist for weeks. Repeated concussions may have cumulative effects, but factors like genetics that influence individual risk and prognosis remain uncertain.