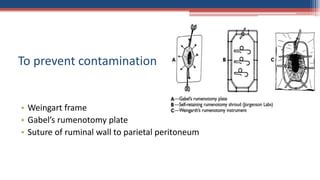

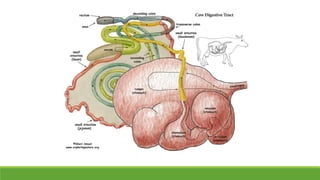

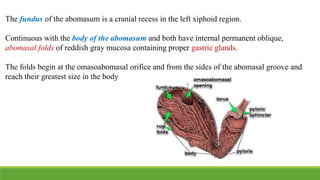

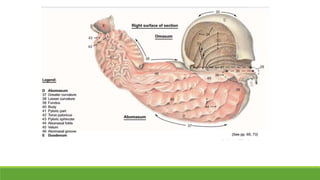

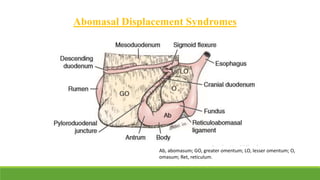

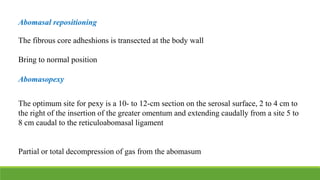

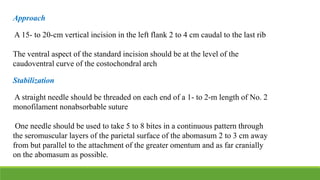

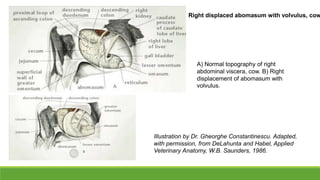

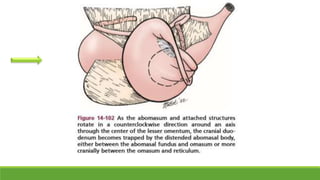

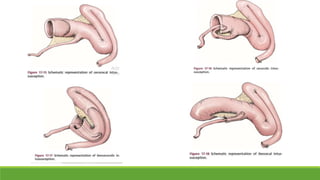

This document discusses surgical management of abdominal affections in bovines. It covers anatomy of the rumen and abomasum. Common abdominal issues addressed include bloat, indigestion, impaction, hernia and torsion. Rumenotomy techniques like the Weingart frame and Gabel's rumenotomy plate are described. Left displacement of the abomasum is the most common surgical condition and approaches like flank omentopexy and abomasopexy are summarized. Post-operative care is also outlined.