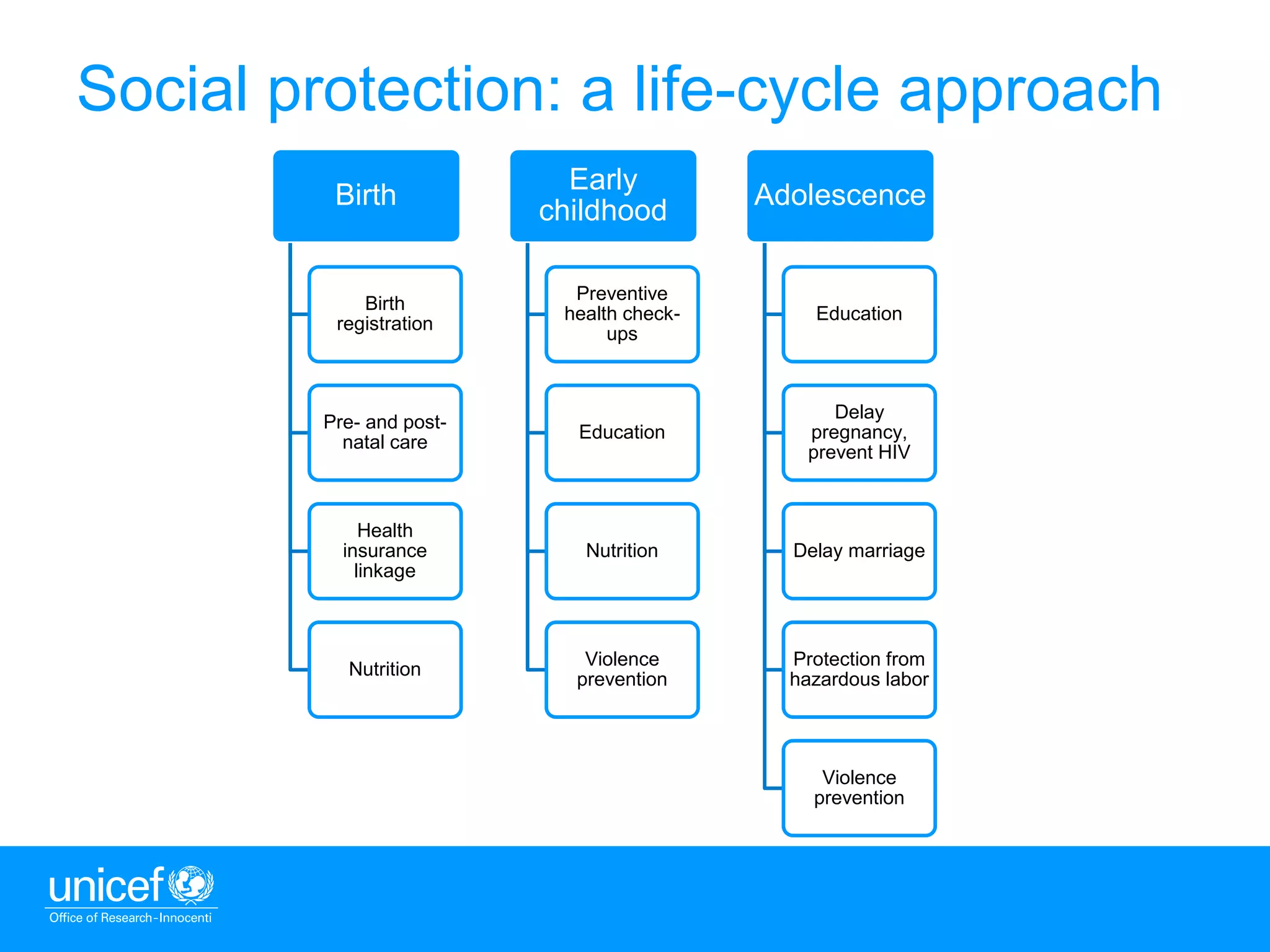

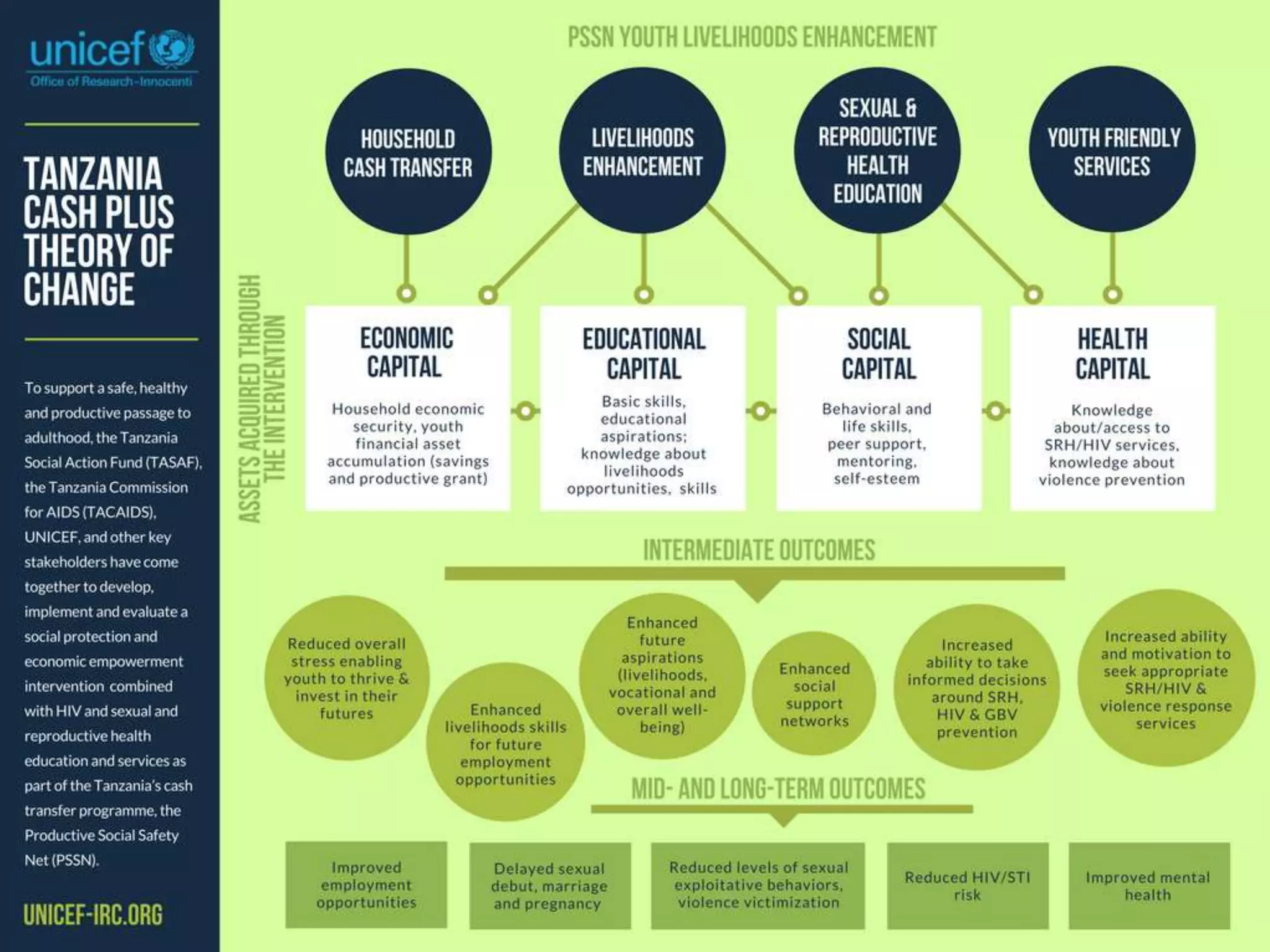

The document discusses social protection approaches for children and adolescents. It outlines UNICEF's focus on using social protection systems to promote children's rights and equitable outcomes. Social protection can be protective, preventive, or transformative. The document then reviews evidence that social cash transfers can positively impact education and child labor outcomes, as well as safe transitions to adulthood by delaying marriage and childbearing. However, impacts vary by context and gender. The document calls for mainstreaming an adolescent lens into social protection programming to better address their needs through program design, features, and indicators.