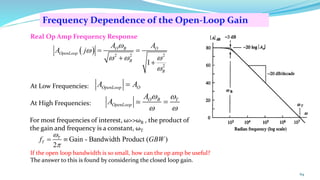

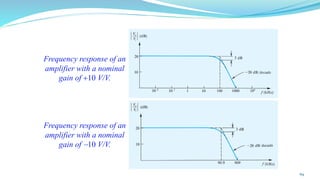

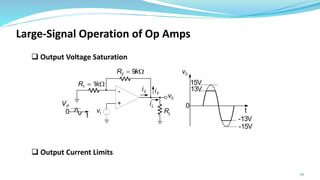

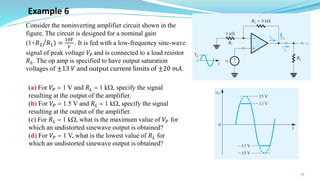

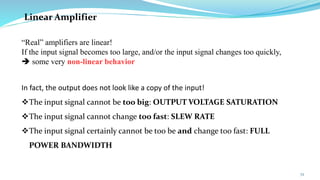

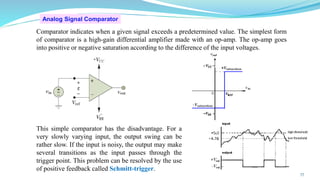

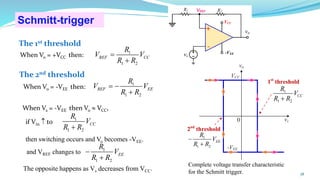

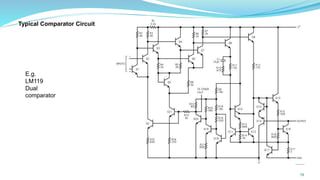

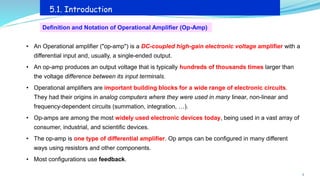

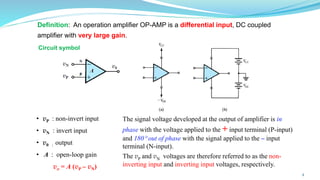

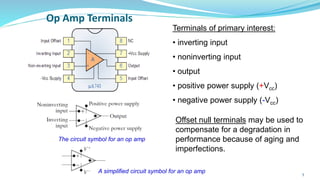

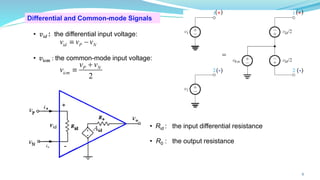

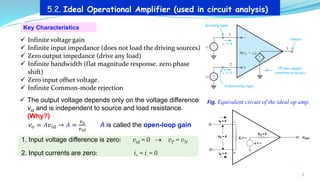

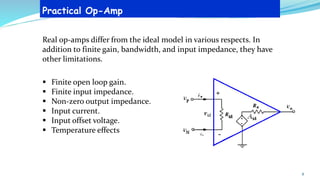

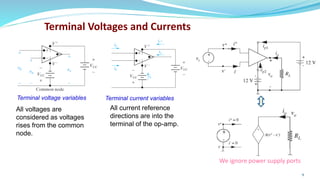

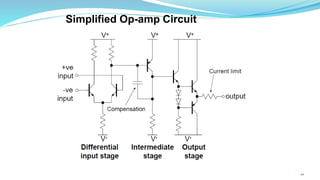

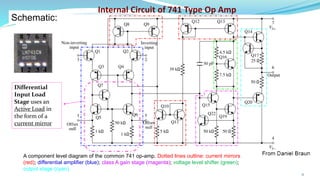

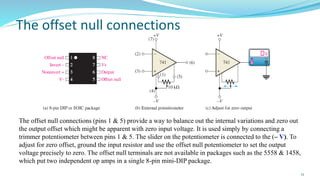

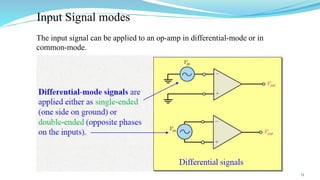

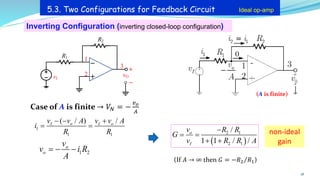

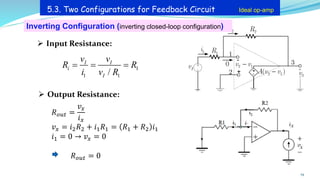

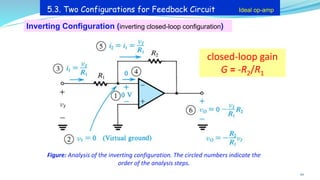

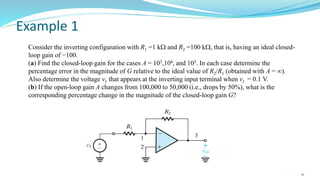

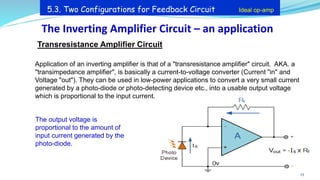

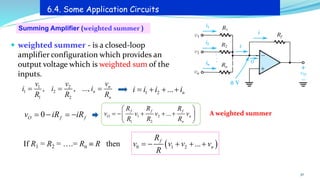

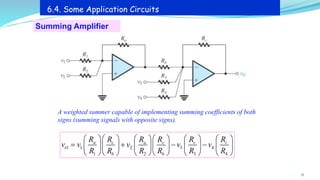

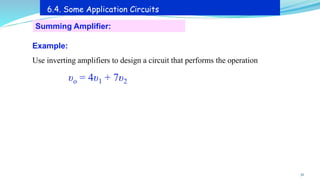

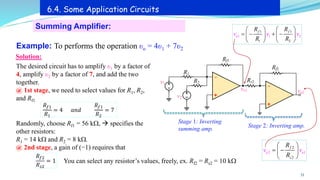

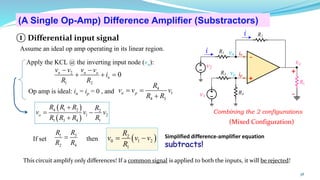

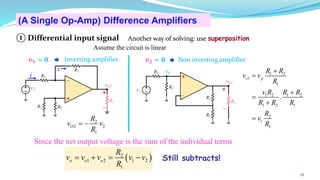

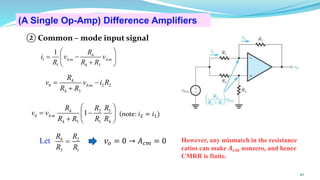

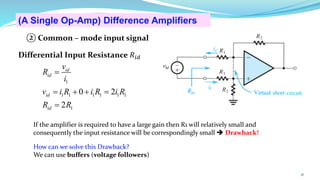

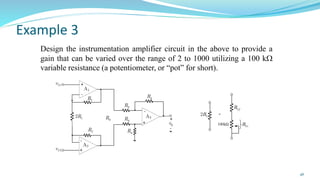

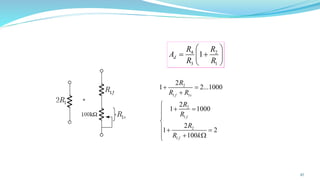

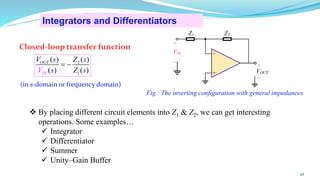

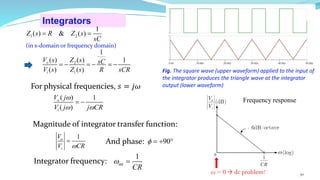

The document provides an in-depth overview of operational amplifiers (op-amps), including their definitions, characteristics, configurations, and applications in electronic circuits. Op-amps are high-gain differential amplifiers that can be used in various configurations for amplifying signals, filters, and buffering circuits. It also covers ideal and practical op-amps, emphasizing their performance traits and common applications such as inverting and non-inverting configurations.

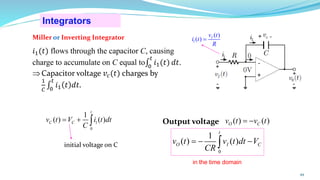

![Example 4

Find the output produced by a Miller integrator in response to an input

pulse of 1-V height and 1-ms width [below figure]. Let R=10 k and

C = 10nF. The op amp is specified to saturate at ±13𝑉.

52](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/5-240615225828-fd2c320c/85/5-Lecture-5-Operational-Amplifier-Upload-pdf-52-320.jpg)