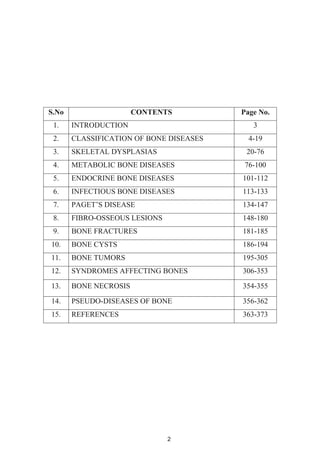

This document provides an overview of bone pathologies and classifications of bone diseases. It begins with an introduction to bone diseases and classifications including by tissue affected, metabolic basis, and decreased/increased bone mass. It then covers specific conditions like skeletal dysplasias, metabolic bone diseases, infections, tumors, fractures and cysts. The document also provides the WHO classification of bone tumors and classifications of fibro-osseous lesions. In summary, the document classifies and describes a wide range of bone diseases, conditions, and lesions.

![104

Clinical presentation

Symptoms can be divided into 2 groups.

Symptoms due to local mass effects of the tumor

Symptoms depend on the size of the intracranial tumor.

Headaches and visual field defects are the most common

symptoms. Visual field defects depend on which part of the

optic nerve pathway is compressed.

The most common manifestation is a bitemporal hemianopsia

due to pressure on the optic chiasm.

Tumor damage to the pituitary stalk might cause

hyperprolactinemia due to loss of inhibitory regulation of

prolactin secretion by the hypothalamus. Damage to normal

pituitary tissue can cause deficiencies of glucocorticoids, sex

steroids, and thyroid hormone.

Loss of end organ hormones is due to diminished anterior

pituitary secretion of corticotropin (ie, adrenocorticotropic

hormone [ACTH]), gonadotropins (eg, luteinizing hormone

[LH], follicle-stimulating hormone [FSH]), and thyrotropin

(ie, thyroid-stimulating hormone [TSH]).

Symptoms due to excess of GH/IGF-I

Soft tissue swelling and enlargement of extremities

Increase in ring and/or shoe size

Hyperhidrosis

Coarsening of facial features

Prognathism

Macroglossia](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2bf2eb75-f34e-4c8f-9abe-4b3fc5b9d875-161028110507/85/23-BONE-PATHOLOGIES-LAMBERT-109-320.jpg)

![150

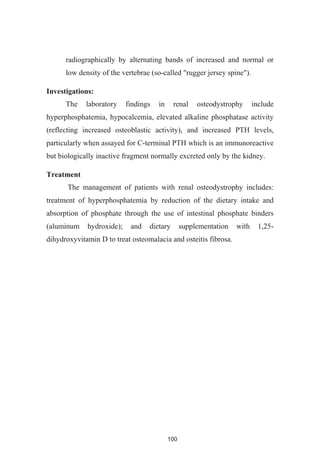

the cause, with disturbances in the normal separative process.61

It is widely

considered to be a developmental (hamartomatous) lesion. Although it is

usually classified as a nonneoplastic disorder, some examples show

neoplastic-like clinical features.62

With the occurrence of polyostotic

cherubism it strongly suggested a fundamental genetic defect of embryonic

origin. The probable mode of inheritance is highly indicative of an

autosomal dominant trait in both the monostotic and polyostotic varieties

of the condition.63

The disease is caused by a somatic mutation of GNAS1 gene

(guanine nucleotide-binding protein, alpha-stimulating activity polypeptide

1; chromosome 20). There is a so-called gain of function mutation

resulting in an increased hyper-function of osteoblasts, melanocytes &

endocrine cells.There is also an increase in IL-6-induced osteoclastic bone

resorption. Due to postzygotic mutation in the GNAS-1 gene, mutation

occurs in undifferentiated stem cells of osteoblasts, melanocytes &

endocrine cells. The progeny of the mutated cell will carry the mutation

and express the mutated gene. The clinical expression is depending on the

size of the cell mass and where in the cell mass the mutation occurs:

a) If mutation occurs in early embryonic life, it results in multiple bone

lesions, cutaneous pigmentation & endocrine disturbances (Mc-

Cune-Albright syndrome).

b) If it occurs in later stages of normal skeletal formation, it results in

multiple bone lesions [polyostotic (Jaffe type)].

c) If it occurs during postnatal life, confined to one bone, results in FD

of a single bone (monostotic fibrous dysplasia).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2bf2eb75-f34e-4c8f-9abe-4b3fc5b9d875-161028110507/85/23-BONE-PATHOLOGIES-LAMBERT-155-320.jpg)

![204

Rarely, lesions that are unusually large and painful occur in

inaccessible sites or involve vital structures. They require radiation

(3-6 Gy [300-600 rad]).

Localized skin disease is best treated with moderate-to-potent

topical steroids (eg, mometasone furoate [Elocon] cream 0.1%,

triamcinolone [Kenalog] cream 0.1%, fluocinolone [Synalar]

ointment 0.025%) or super-potent topical steroids (eg, clobetasol

propionate 0.05%).

In cases of severe cutaneous involvement, topical nitrogen mustard

(20% solution) may be used, based on its easy administration

especially in outpatient settings and freedom from adverse effects.

For single lymph node infiltration, excision is the treatment of

choice.

Regional lymph node enlargement can be treated with a short course

of systemic steroids.

Treatment-resistant nodes with sinus tracts to the skin may require

systemic chemotherapy.

Multisystem disease

Systemic chemotherapy is indicated for cases of multisystem disease

and those cases of single-system disease that are not responsive to

other treatment.

The combination of cytotoxic drugs and systemic steroids is

effective. Low-to-moderate doses of methotrexate, prednisone, and

vinblastine are used.

BONE LESIONS OF GAUCHER'S DISEASE41,42

Gaucher's disease, an autosomal recessive genetic disorder, is a

lysosomal storage disease caused by a deficiency of the enzyme](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2bf2eb75-f34e-4c8f-9abe-4b3fc5b9d875-161028110507/85/23-BONE-PATHOLOGIES-LAMBERT-209-320.jpg)

![246

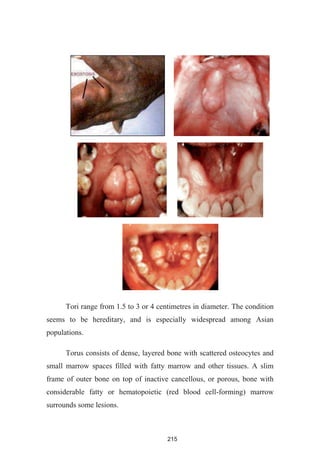

MALIGNANCIES OF THE JAW93,94,95,96

PLASMA CELL NEOPLASMS

MULTIPLE MYELOMA93,96

Multiple myeloma (also known as myeloma, plasma cell

myeloma, or as Kahler's disease) is a type of cancer of plasma cells. First

described in 1848, multiple myeloma is a disease characterized by a

proliferation of malignant plasma cells and a subsequent overabundance of

monoclonal paraprotein.

Pathophysiology

Myeloma begins when a plasma cell becomes abnormal. The

abnormal cell divides to make copies of itself. The new cells divide again

and again, making more and more abnormal cells. The abnormal plasma

cells are myeloma cells. Myeloma cells make antibodies called M proteins.

In time, myeloma cells collect in the bone marrow. They may crowd

out normal blood cells. Myeloma cells also collect in the solid part of the

bone. The disease is called "multiple myeloma" because it affects many

bones. (If myeloma cells collect in only one bone, the single mass is called

a plasmacytoma.)

The proliferation of plasma cells may interfere with the normal

production of blood cells, resulting in leukopenia, anemia, and

thrombocytopenia. The cells may cause soft tissue masses

(plasmacytomas) or lytic lesions in the skeleton. A chromosomal

translocation between the immunoglobulin heavy chain gene (on the

fourteenth chromosome, locus 14q32) and an oncogene (often 11q13,

4p16.3, 6p21, 16q23 and 20q11[6]

) is frequently observed in patients with

multiple myeloma. This mutation results in dysregulation of the oncogene](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2bf2eb75-f34e-4c8f-9abe-4b3fc5b9d875-161028110507/85/23-BONE-PATHOLOGIES-LAMBERT-251-320.jpg)