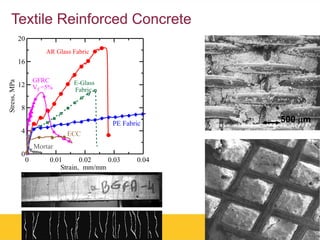

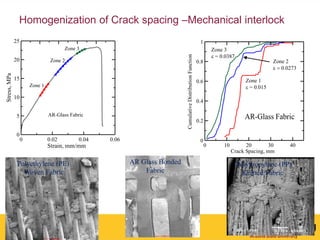

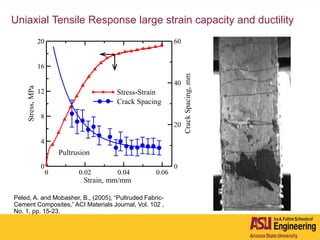

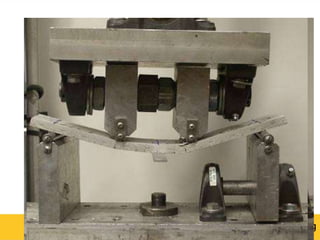

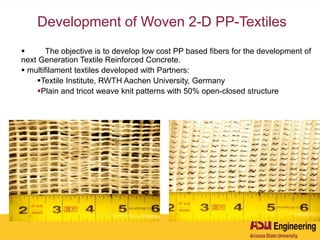

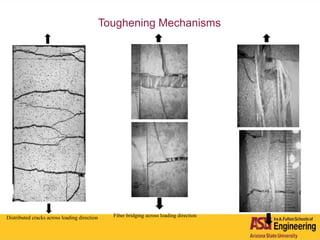

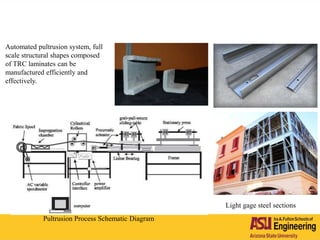

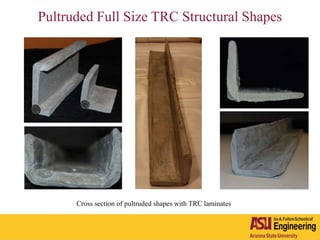

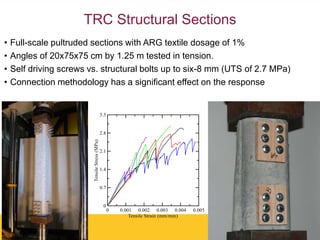

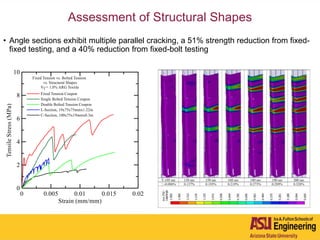

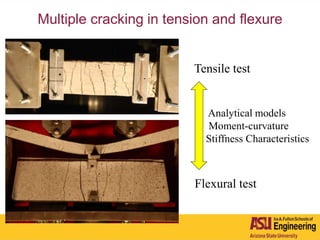

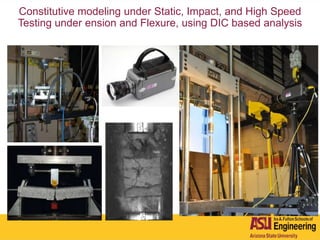

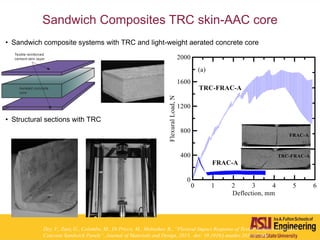

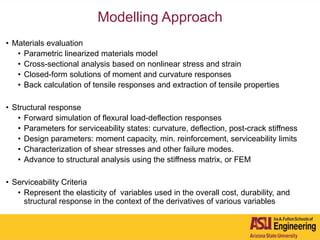

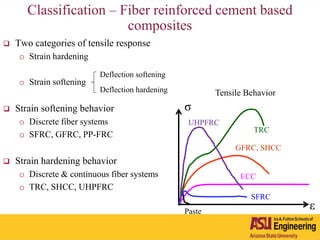

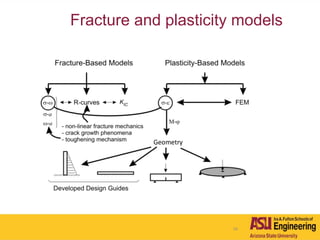

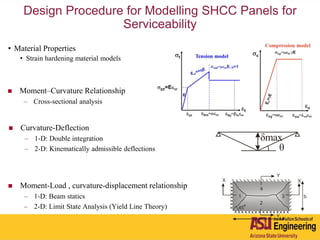

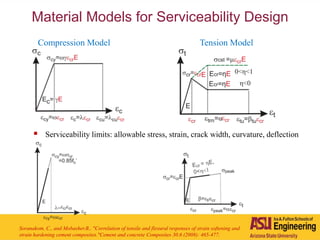

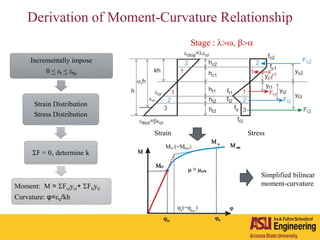

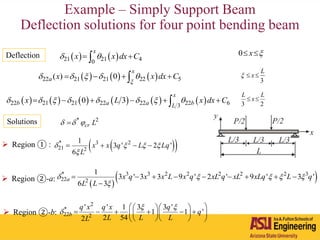

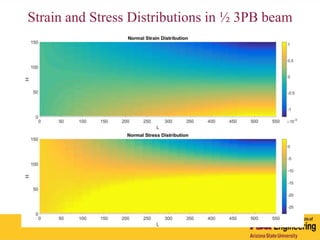

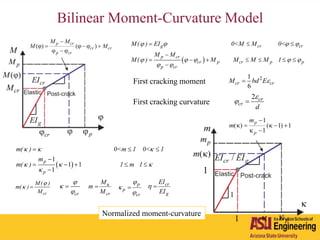

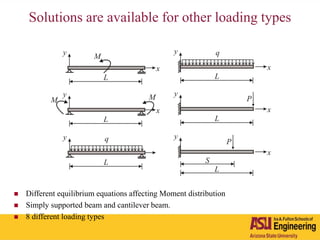

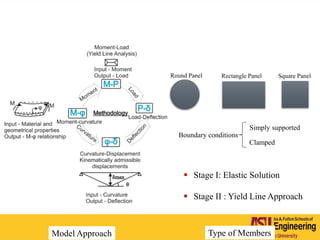

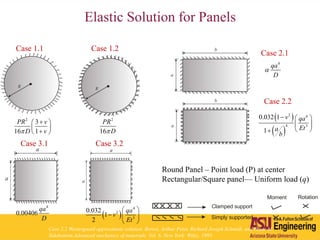

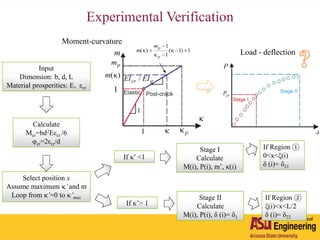

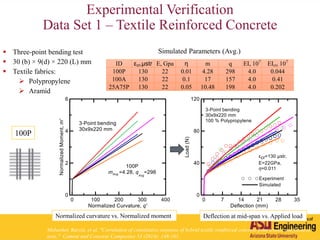

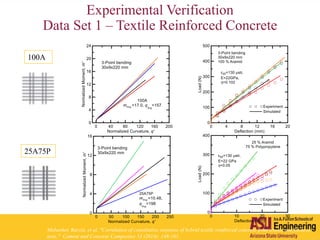

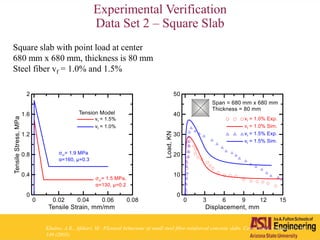

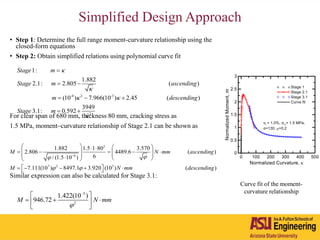

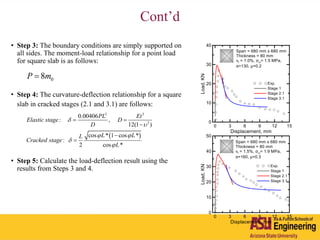

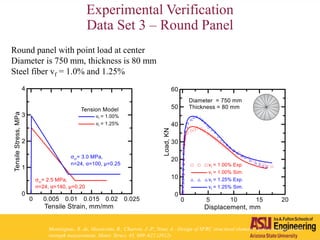

The document outlines Barzin Mobasher's presentation on textile reinforced concrete structural sections. The presentation covers the introduction of textile reinforced concrete and its sustainability aspects. It then discusses directions for textile reinforced concrete and developing structural sections using ultra-high performance concrete, fiber reinforced concrete, and textile reinforced concrete systems. The presentation also reviews experimental characterization of distributed cracking, parametric material models, analytical load-deflection solutions, experimental verification, and conclusions.