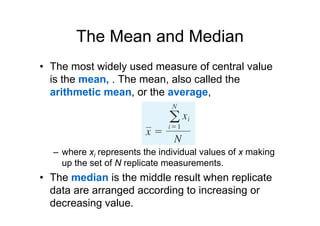

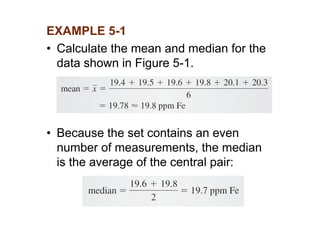

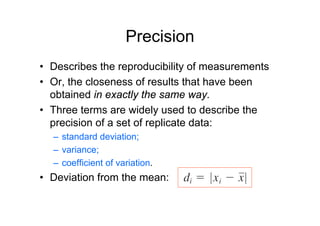

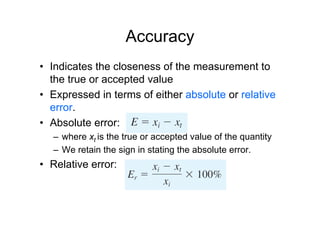

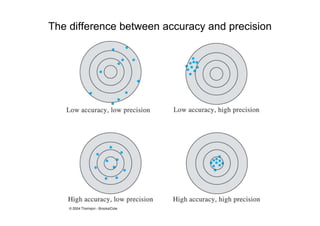

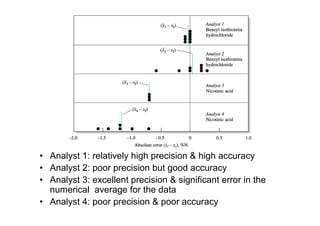

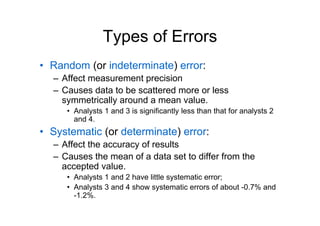

The document discusses the importance of data quality and the types of errors in chemical analysis, emphasizing that measurements involve uncertainties that can be managed but not eliminated. It outlines how precision and accuracy are determined through statistical measures and experiments, as well as different types of systematic and random errors that affect analytical results. Techniques for error detection and reduction, such as calibration, use of standard reference materials, and blank determinations, are also highlighted.