This document summarizes a new type of three-axial MEMS gyroscope that uses frequency modulation (FM) as its working principle. It begins by describing the dynamics of MEMS gyroscopes, including equations of motion for both an ideal point mass gyroscope and a real distributed mass gyroscope. It then introduces the FM working principle and how it offers improved stability compared to existing amplitude modulated gyroscopes. The document proposes the mechanical design of the first three-axial FM gyroscope, which overcomes limitations of typical fabrication processes. Preliminary experimental tests on a prototype validate the model and simulation results used in the design process.

![+ ∧ + ∧ + ∧ +

+ + ∧ ∧ + = −

m m m m

m m

x Ω x Ω x Ω v

a Ω Ω x kx F bx

¨ ˙ 2 ˙

˙

0

0 (3)

where =a v˙0 0 is the external acceleration.

In the following, we will consider the external velocity v0 and ac-

celeration a0 small enough to make the terms ∧mΩ v0 and ma0 neg-

ligible in equation (3). For later use, one can also re-write the equations

of motion (3) in the form:

+ + + + + +

+ + + + + +

+ + + + + +

+ + =

α α α

α α α β β

β β β β β

β β

m m

m m

x bx kx x

x

x F

¨ ˙ ( Ω˙ Ω˙ Ω˙ )

2 ( Ω Ω Ω ) ˙ ( Ω Ω

Ω ( )Ω Ω ( )Ω Ω

( )Ω Ω ) ,

x

x

y

y

z

z

x

x

y

y

z

z

xx

x

yy

y

zz

z

xy yx

x y

xz zx

x z

yz zy

y z

2 2

2

(4)

where the matrices αi

and βij have components:

= −α ε ,hk

i

ihk (5)

and

= −β δ δ δ δ ,hk

ij

ih jk ij hk (6)

with δhk the Kronecker delta and εihk the Levi-Civita symbol defined as:

=

⎧

⎨

⎩

=

− =ε

i h k x y z y z x z x y

i h k z y x x z y y x z

1 if ( , , ) ( , , ), ( , , ), ( , , )

1 if ( , , ) ( , , ), ( , , ), ( , , )

0 otherwise.

ijk

(7)

Note that the matrices αi

contain the so-called angular gains that

quantify the coupling in terms of modal masses between the two modes

coupled by the Coriolis force. For a pointwise mass structure like the

one considered in this Section, they are equal to one in modulus, but in

case of real gyroscopes with distributed mass, like the ones studied in

the following, they will be smaller than one and will play a crucial role.

By assuming resonant frequencies =ω k m/oi i

2

much larger than the

applied rate signals Ωi and supposing only slow changes of Ωi, it is

possible to neglect all the terms coming from the drag acceleration in

equation (4) and consider only the Coriolis force that couples the three

components of motion of the gyroscope proof mass. Equation (4), then,

reads:

+ + + + + =α α αm mx bx kx x F¨ ˙ 2 ( Ω Ω Ω ) ˙ .x

x

y

y

z

z (8)

2.2. Equations of motion for a real gyroscope

Real fabricated gyroscopes cannot be approximated as point mass

structures because of their complex mechanical designs made by rigid

masses and deformable structural elements, endowed with non-negli-

gible mass, properly combined. The effect of all deformable elements

(or springs) can be lumped in equivalent springs acting at the centroid x

of the device. Similarly, the non-conservative forces can be described by

an equivalent damping matrix.

Moreover, real gyroscopes are affected by fabrication imperfections

(i.e. small asymmetries in the deformable elements), as a consequence,

it is no more possible to consider the three translational motions of the

mass as decoupled. Extra-diagonal terms in the equivalent stiffness and

damping matrices are added to take into account such fabrication im-

perfections and consequent motion coupling.

The first three real modes of the structure, which are designed to be

three ideal pure translational modes in the directions x, y and z, are

actually characterized by non-uniform displacement fields, s (see

Fig. 2b), that are here represented as:

=

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

= φx y z t

φ x y z u t

φ x y z u t

φ x y z u t

ts x u( , , , )

( , , ) ( )

( , , ) ( )

( , , ) ( )

( ) ( ),

x

x

y

y

z

z (9)

where φ x( ) is the diagonal matrix containing the three nondimensional

modal shape functions φx, φy, φz describing the three main modes

actuated by on board actuators in a real gyroscope (see Section 5) and

=t u t u t u tu ( ) [ ( ), ( ), ( )]T

x y z is the time evolution of the system's re-

sponse with ux, uy and uz the amplitudes of the three modes. Note that,

rotational degrees of freedom will not be included in the present for-

mulation. This simplification is justified by the assumption that a

proper mechanical design would allow to obtain rotational modes at

very high frequencies with respect to those of the translational modes.

Denoting by ρ the density of the distributed mass with volume V, the

kinetic and potential energy of the real gyroscope read:

T

V V

∫= ⋅ = + + ∧ +

= ⋅ +

ρ Vv v v v s Ω s x

s x k s x

d with ˙ ( ),

( ) ( ) ,

V

eq ext

1

2 0 0

1

2 (10)

where keq is the non-diagonal equivalent stiffness matrix. The vector of

the generalized forces Q is constituted by the damping forces − b s x˙ ( )eq

with beq equivalent damping matrix that takes into account the fabri-

cation imperfections through extra-diagonal terms.

Neglecting again contributions coming from the external velocity

and acceleration, by substituting equation (10) into (2), the equations

of motion of a real three-axial gyroscope are derived. They read:

+ + + + + + +

+ + + + + + +

+ + + + +

α α α α

α α β β β β

β β β β β

mu bu ku u

u

u = F

¨ ˙ (Ω˙ ˆ Ω˙ ˆ Ω˙ ˆ ) 2(Ω ˆ

Ω ˆ Ω ˆ ) ˙ (Ω ˆ Ω ˆ Ω ˆ Ω Ω ( ˆ

ˆ ) Ω Ω ( ˆ ˆ ) Ω Ω ( ˆ ˆ ))

x

x

y

y

z

z

x

x

y

y

z

z

x

xx

y

yy

z

zz

x y

xy

yx

x z

xz zx

y z

yz zy

2 2 2

(11)

where, m is the diagonal mass matrix whose non-zero elements are the

modal masses of the three modes of interest, k is the stiffness matrix

that contains extra-diagonal terms coming from the fabrication im-

perfections, αˆi

and βˆij

, with =i j x y z, , , , are the coupling matrices that

arise because of the presence of the external angular velocities.

The matrices m, b and k have components mhk, bhk and khk re-

spectively with h and k taking values x, y and z. The terms of the ma-

trices m, b, k, αˆ and βˆ are defined as:

∫

∫

∫

= =

= =

= =

= − =

= − =

m ρφ φ δ V h k x y z

b φ b φ h k x y z

k φ k φ h k x y z

α ρε φ φ V i h k x y z

β ρ φ φ δ δ δ δ φ V i j h k x y z

x x

x x

d , , ,

( )( ) ( ) , , ,

( )( ) ( ) , , ,

ˆ d , , , ,

ˆ ( ( ) )d , , , , ,

hk

V

h k

hk

hk

h

eq hk

k

hk

h

eq hk

k

hk

i

V

ihk

h k

hk

ij

V

h k

ih jk ij hk

h 2

(12)

where the summation over repeated indices is not considered.

The angular gain αhk

i

with =i h k x y z, , , , of the distributed-mass

gyroscope is defined as the ratio between αˆhk

i

and the modal mass mhh

as:

= − =α

α

m

i h k x y z

ˆ

(distributed mass) , , , , .hk

i hk

i

hh (13)

Note that in the limit of pointwise mass →φ 1h , →m mhh and

equation (13) coincides with equation (5). In general, since φh vary in

space, the entries of the angular gain matrices αi

differ from unit.

Finally, note that the external velocities and accelerations can be

neglected even when the external acceleration is not negligible; it is

possible in fact to null their contributions through the design of a dif-

ferential mechanical structure as shown in Zega et al. (2017b).

3. Phasor analysis

The equations of motion presented in the previous section are, here,

solved through the phasor method (see Kline et al. (2013b)) both for the

case of an ideal point-mass gyroscope and for a real gyroscope.

V. Zega et al. European Journal of Mechanics / A Solids 70 (2018) 203–212

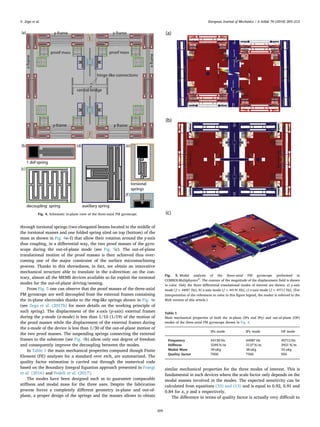

205](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1-s2-200404024819/85/1-s2-0-s0997753817308902-main-3-320.jpg)

![3.1. Ideal gyroscope

Accounting for relations (5)–(6), the vectorial equation (4) can be

written in the scalar form:

+ − + + − + +

+ − + + =

+ − + + − + +

+ + + − =

+ − + + − + +

+ − + + =

mx b x m y m z k x m x

m y m z F

my b y m z m x k y m y

m x m z F

mz b z m x m y k z m z

m x m y F

¨ ˙ 2 Ω ˙ 2 Ω ˙ (Ω Ω )

(Ω Ω Ω˙ ) (Ω˙ Ω Ω ) ,

¨ ˙ 2 Ω ˙ 2 Ω ˙ (Ω Ω )

(Ω Ω Ω˙ ) (Ω Ω Ω˙ ) ,

¨ ˙ 2 Ω ˙ 2 Ω ˙ (Ω Ω )

(Ω Ω Ω˙ ) (Ω˙ Ω Ω ) .

x z y x z y

x y z y x z x

y x z y z x

x y z z y x y

z y x z x y

x z y x y z z

2 2

2 2

2 2

(14)

In order to make clearer the link between the results for the ideal

gyroscope and those for a real one, we keep here the notation with αhk

i

and βhk

ij

, without substituting their values given in (5)–(6). Equation

(14) will hence be written in the form:

⎜ ⎟

⎜ ⎟

⎜ ⎟ ⎜ ⎟

⎜ ⎟

+ + + + + + +

+ ⎛

⎝

+ ⎞

⎠

+ + =

+ + + + + ⎛

⎝

+ ⎞

⎠

+

+ ⎛

⎝

+ ⎞

⎠

+ ⎛

⎝

+ ⎞

⎠

=

+ + + + + + +

+ + + ⎛

⎝

+ ⎞

⎠

=

mx b x mα y mα z k x m β β x

m β α y m β α z F

my b y mα z mα x k y m β β y

m β α x m β α z F

mz b z mα x mα y k z m β β z

m β α x m β α y F

¨ ˙ 2 Ω ˙ 2 Ω ˙ ( Ω Ω )

Ω Ω Ω˙ ( Ω Ω Ω˙ ) ,

¨ ˙ 2 Ω ˙ 2 Ω ˙ Ω Ω

Ω Ω Ω˙ Ω Ω Ω˙ ,

¨ ˙ 2 Ω ˙ 2 Ω ˙ ( Ω Ω )

( Ω Ω Ω˙ ) Ω Ω Ω˙ ,

x xy

z

z xz

y

y x x

z

z x

y

y

xy

xy

x y xy

z

z xz

xz

x z xz

y

y x

y yz

x

x yx

z

z y y

z

z y

x

x

yx

yx

x y yx

z

z yz

yz

z y yz

x

x y

z zx

y

y zy

x

x z z

x

x z

y

y

zx

zx

x z zx

y

y zy

zy

y z zy

x

x z

2 2

2 2

2 2

(15)

where the double identical index has been substituted by a single one

for the sake of clarity.

In order to compensate for losses and to sustain the oscillation of the

gyroscope proof mass according to the three translational modes of

interest, the excitation forces can be written in the form

= F e F e F eF [(i ) , (i ) , (i ) ]T

x

ϕ

y

ϕ

zs

ϕi i ix y z with i imaginary unit, since at re-

sonance, the force needed to sustain the oscillation is in quadrature

with the displacement. Moreover, in the control circuit, the phase of the

forcers are derived directly from the phase of the gyroscope output, so it

is possible to say that, supposing a high quality factor Q for all the three

resonators, the complex solution of (15) can be constituted by three

sinusoidal oscillations near to the mechanical resonant frequency of

each axis, of the form:

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥=

⎡

⎣

⎢

⎢

⎤

⎦

⎥

⎥

=u

u

u

u

A e

A e

A e

,

x

y

z

x

ϕ

y

ϕ

z

ϕ

i

i

i

x

y

z

(16)

where Ax, Ay, Az, ∫=ϕ ω τ τ( )dx

t

x0

, ∫=ϕ ω τ τ( )dy

t

y0

and ∫=ϕ ω τ τ( )dz

t

z0

represent the system unknowns. Ax, Ay, Az are the real, time dependent

amplitudes of the displacements of the proof mass along the three di-

rections x y, and z, while ω ω,x y and ωz are the actual resonant fre-

quencies of the three translational modes along the − −x y, and z-di-

rections. If no external angular rate is applied, =ω ωi oi with ωoi natural

frequency of the −i mode and = +ϕ ω t ψi oi i. In the following we in-

troduce the notation = −ϕ ϕ ϕΔ ij i j with =i x y z, , .

Note that Ax, Ay, Az, ωx, ωy and ωz are slowly varying relatively to

the mechanical resonant frequencies of the system, as a consequence, in

the acceleration expression, the terms containing A¨x, A¨y, A¨z, ω˙ x, ω˙ y and

ω˙ z can be neglected, as they are negligible if compared to ω A˙x x, ω A˙y y,

ω A˙z z, ωx

2

, ωy

2

and ωz

2

, respectively. Moreover, it is reasonable to assume

that the angular rate and the displacement amplitudes are slowly

varying with respect to the resonance frequency.

Under these hypotheses, by substituting equation (16) into (15) and

dividing the three equations for e ϕi x, e ϕi y and e ϕi z respectively, three

complex equations are obtained. By nulling both the real and the

imaginary parts, it is possible to obtain an expression for A˙x, A˙y, A˙ z, ωx

2

,

ωy

2

and ωz

2

.

The expressions for A˙x, A˙y and A˙ z are reported in Appendix A since

they will not be used in the following, while the expressions for ωx

2

, ωy

2

and ωz

2

under the assumption ≪A A ω˙ i i i for =i x y z, , read:

= + + +

+ + +

+ +

ω ω β β

β ϕ β ϕ

α ω ϕ α ω ϕ

Ω Ω

Ω Ω cos(Δ ) Ω Ω cos(Δ )

2 Ω sin(Δ ) 2 Ω sin(Δ ),

x ox x

z

z x

y

y

xy

xy

x y

A

A xy xz

xz

x z

A

A xz

xy

z

z y

A

A xy xz

y

y z

A

A xz

2 2 2 2

y

x

z

x

y

x

z

x (17)

= + + +

+ + +

− +

ω ω β β

β ϕ β ϕ

α ω ϕ α ω ϕ

Ω Ω

Ω Ω cos(Δ ) Ω Ω cos(Δ )

2 Ω sin(Δ ) 2 Ω sin(Δ ),

y oy y

x

x y

z

z

yx

yx

x y

A

A xy yz

yz

y z

A

A yz

yx

z

z x

A

A xy yz

x

x z

A

A yz

2 2 2 2

x

y

z

y

x

y

z

y (18)

= + + +

+ + +

− −

ω ω β β

β ϕ β ϕ

α ω ϕ α ω ϕ

Ω Ω

Ω Ω cos(Δ ) Ω Ω cos(Δ )

2 Ω sin(Δ ) 2 Ω sin(Δ ).

z oz z

x

x z

y

y

zy

zy

y z

A

A yz zx

zx

x z

A

A xz

zx

y

y x

A

A xz zy

x

x y

A

A yz

2 2 2 2

y

z

x

z

x

z

y

z (19)

By defining the velocity amplitudes as =v A ωi i i for =i x y z, , and

solving the second order equation (17) with respect to ωx, the following

expression is found:

= +

+ + +

+ + +

ω ϕ

ϕ α ϕ

α ϕ ω D

Ω Ω cos(Δ )

Ω Ω cos(Δ ) Ω sin(Δ )

Ω sin(Δ ) ,

x

β

ω x y

v

v xy

β

ω x z

v

v xz xy

z

z

v

v xy

xz

y

y

v

v xz ox x

2

2

2

xy

xy

oy

y

x

xz

xz

oz

z

x

y

x

z

x (20)

where

⎜ ⎜ ⎟

⎟

= + + ⎛

⎝

⎛

⎝

⎞

⎠

+

+ + +

+ ⎞

⎠

D β β ϕ

ϕ α ϕ

α ϕ

Ω Ω Ω Ω cos Δ

Ω Ω cos(Δ ) Ω sin(Δ )

Ω sin(Δ ) .

x x

z

z x

y

y

β

ω x y

v

v xy

β

ω x z

v

v xz xy

z

z

v

v xy

y

y

v

v

2 2

2

2

xz xz

2

xy

xy

oy

y

x

xz

xz

oz

z

x

y

x

z

x

(21)

By proceeding in the same way for the other two axes and by noting

that ≫ω Doi i

2

for =i x y z, , , the instantaneous frequencies of oscillation

along the x-, y- and z-axis are derived:

= + +

+ +

+ +

ω ω ϕ

ϕ

α ϕ α ϕ

Ω Ω cos(Δ )

Ω Ω cos(Δ )

Ω sin(Δ ) Ω sin(Δ ),

x ox

β

ω x y

v

v xy

β

ω x z

v

v xz

xy

z

z

v

v xy xz

y

y

v

v xz

2

2

xy

xy

oy

y

x

xz

xz

oz

z

x

y

x

z

x (22)

= + +

+ +

+ −

ω ω ϕ

ϕ

α ϕ α ϕ

Ω Ω cos(Δ )

Ω Ω cos(Δ )

Ω sin(Δ ) Ω sin(Δ ),

y oy

β

ω x y

v

v xy

β

ω y z

v

v yz

yz

x

x

v

v yz yx

z

z

v

v xy

2

2

yx

yx

ox

x

y

yz

yz

oz

z

y

z

y

x

y (23)

= + +

+ +

− −

ω ω ϕ

ϕ

α ϕ α ϕ

Ω Ω cos(Δ )

Ω Ω cos(Δ )

Ω sin(Δ ) Ω sin(Δ ).

z oz

β

ω x z

v

v xz

β

ω y z

v

v yz

zx

y

y

v

v xz zy

x

x

v

v yz

2

2

zx

zx

ox

x

z

zy

zy

oy

y

z

x

z

y

z (24)

3.2. Real gyroscope

By applying the same procedure to the equation of motion (11) of a

V. Zega et al. European Journal of Mechanics / A Solids 70 (2018) 203–212

206](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1-s2-200404024819/85/1-s2-0-s0997753817308902-main-4-320.jpg)