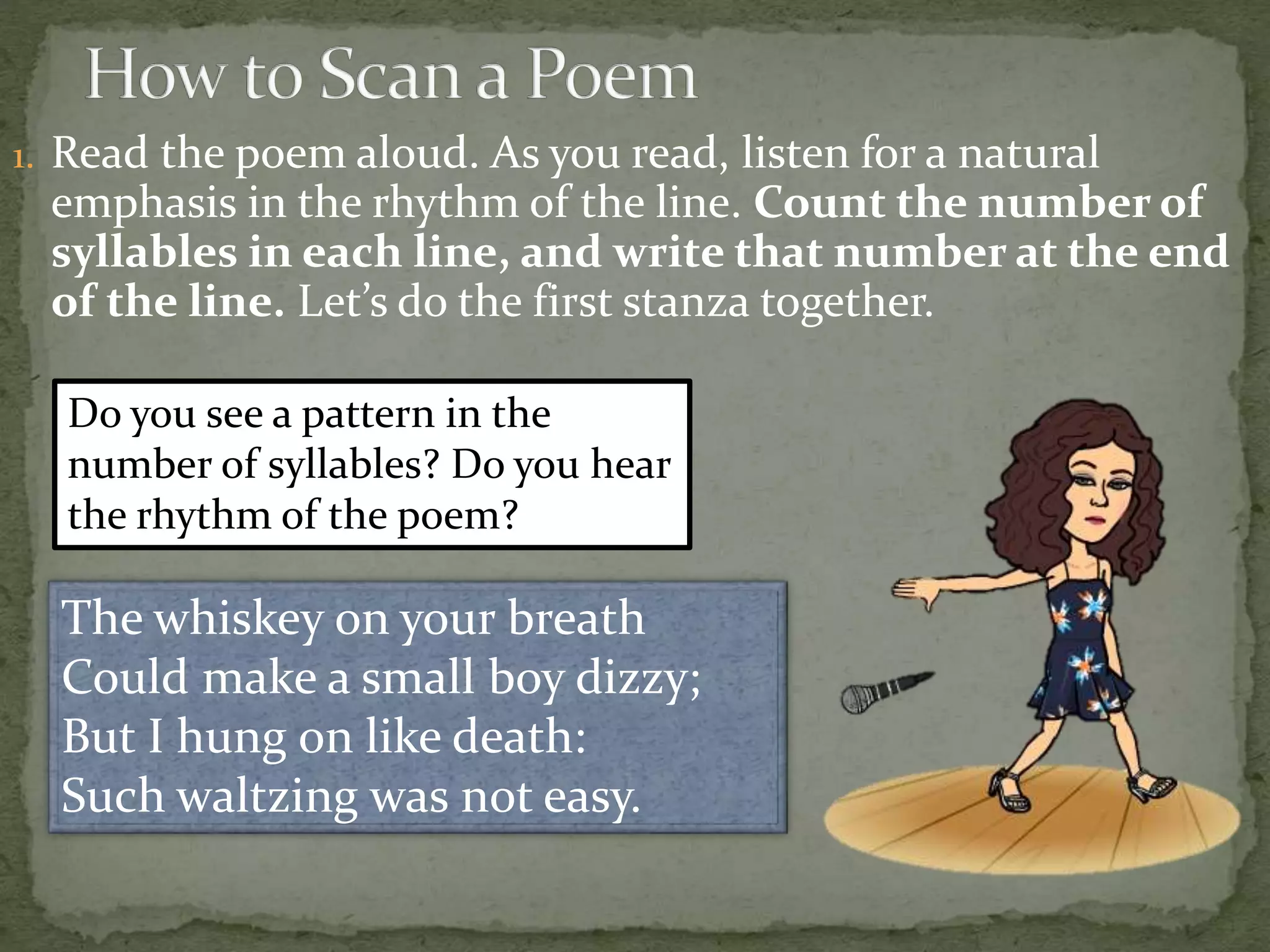

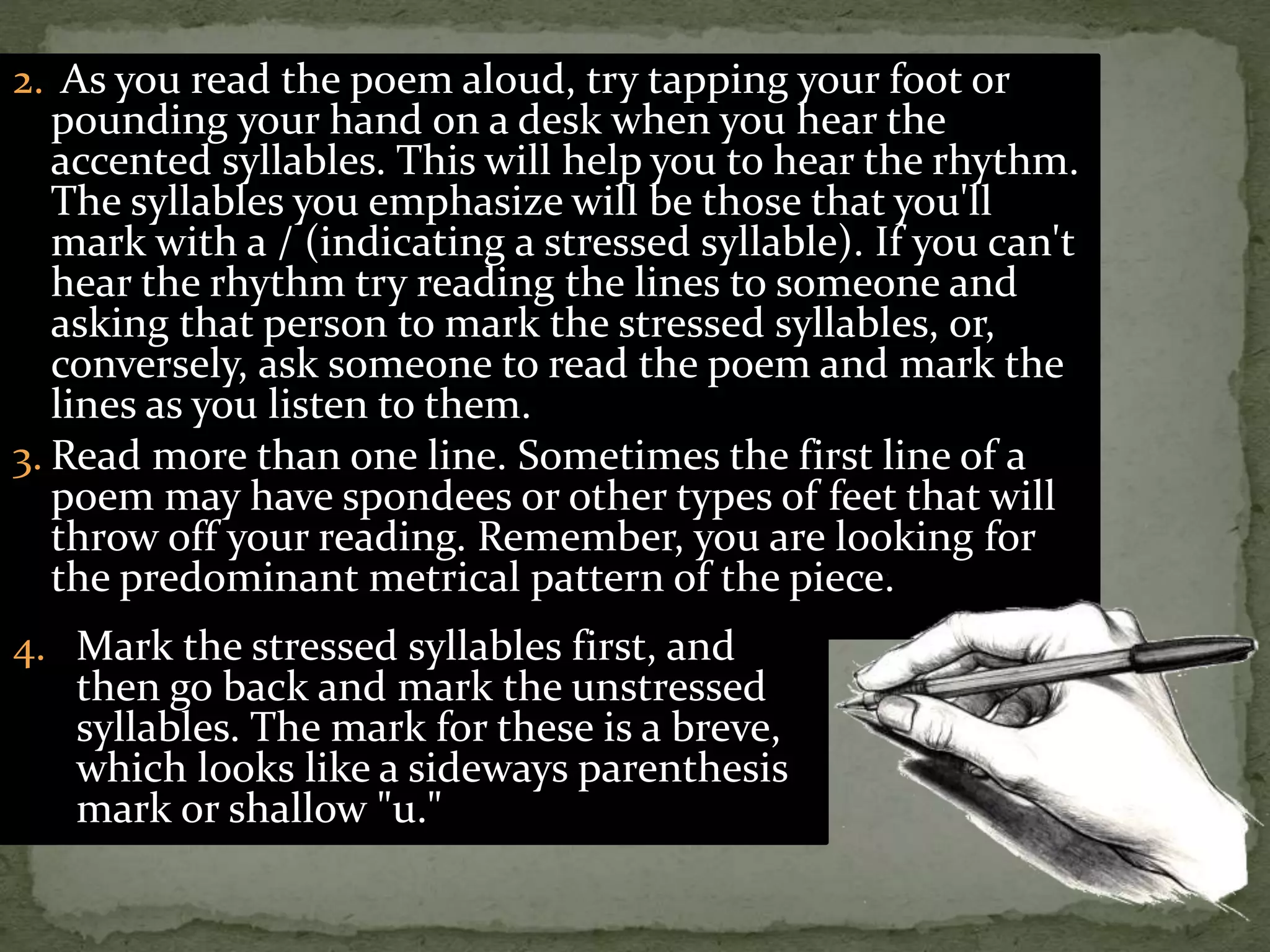

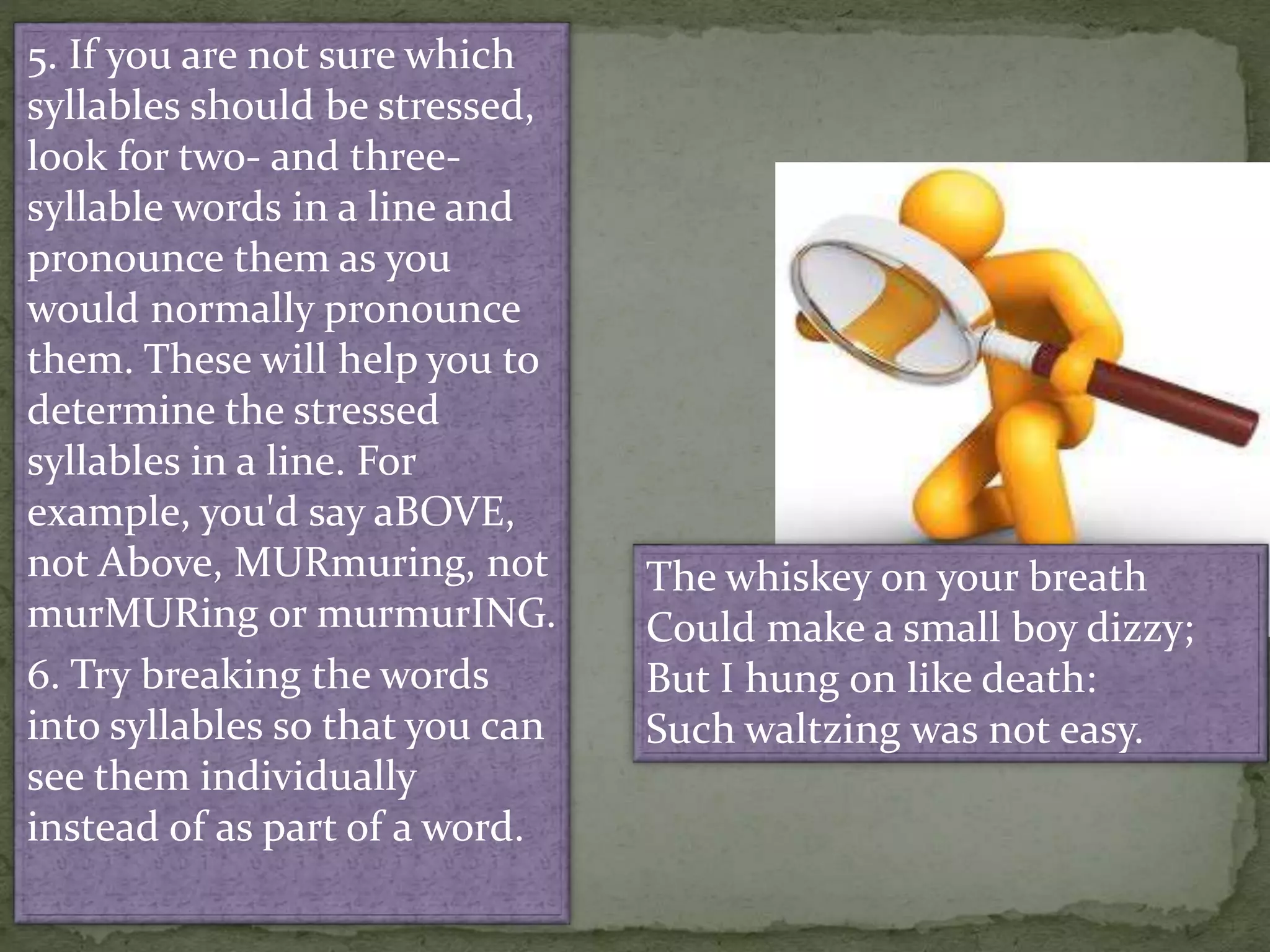

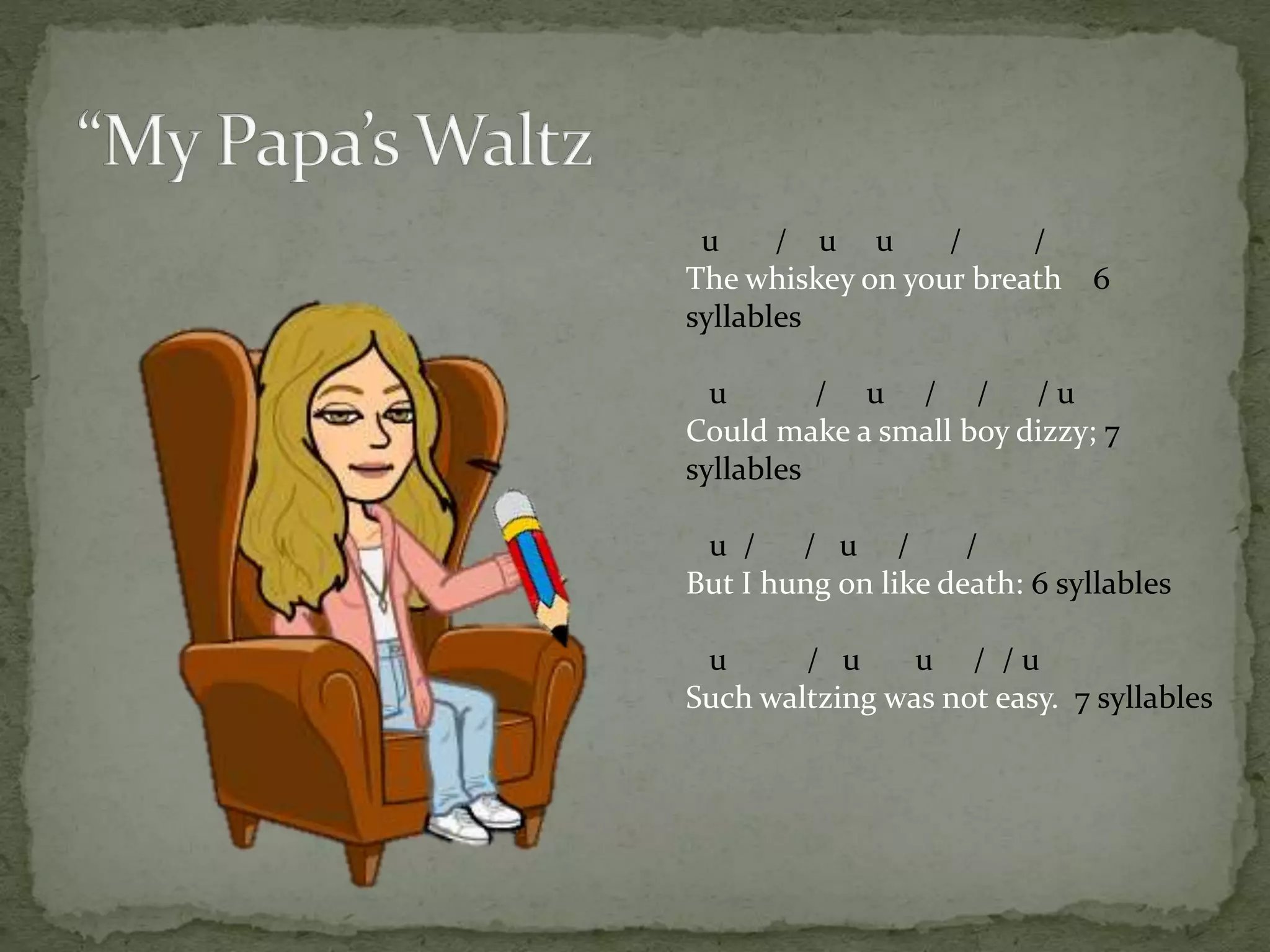

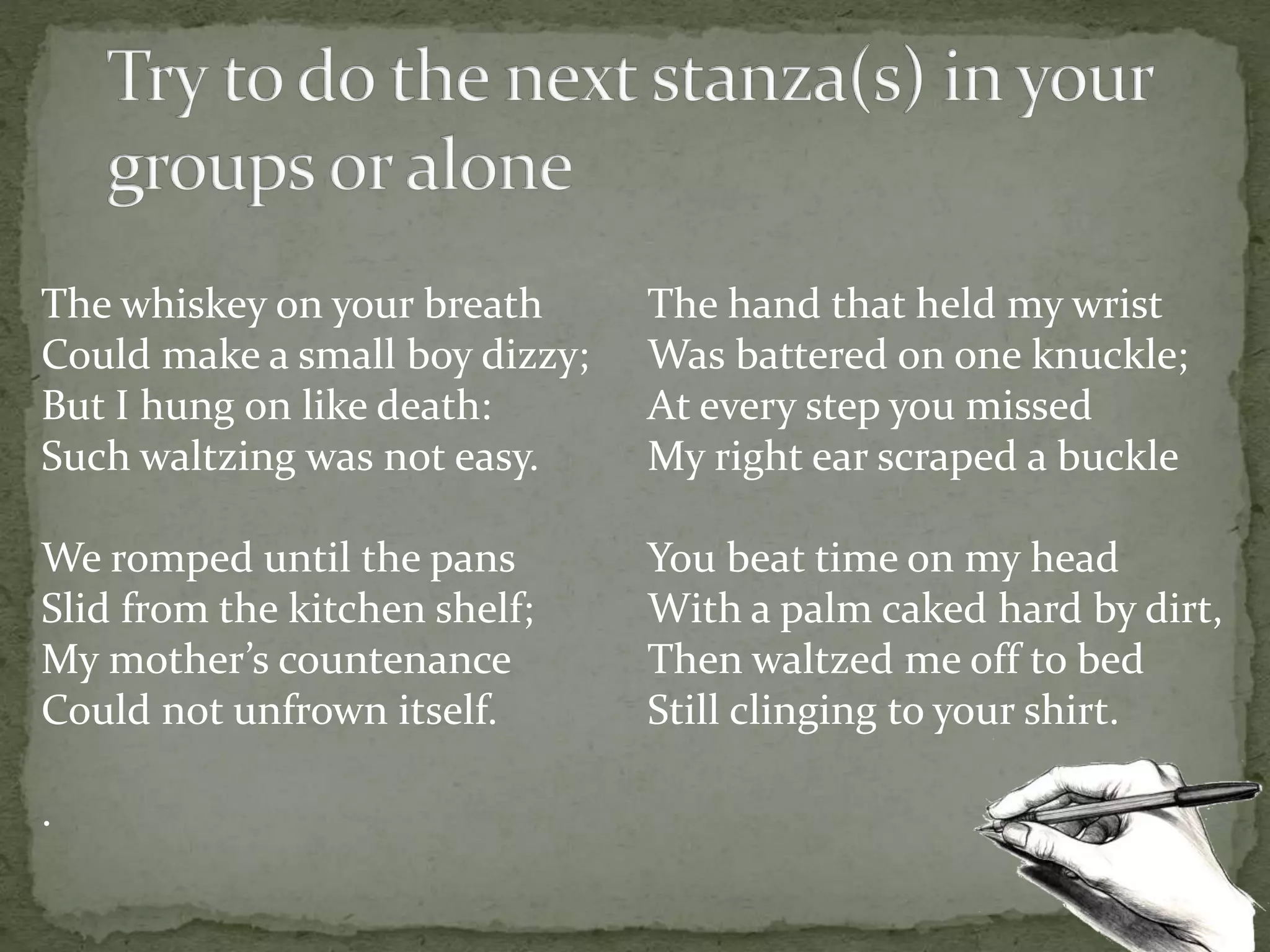

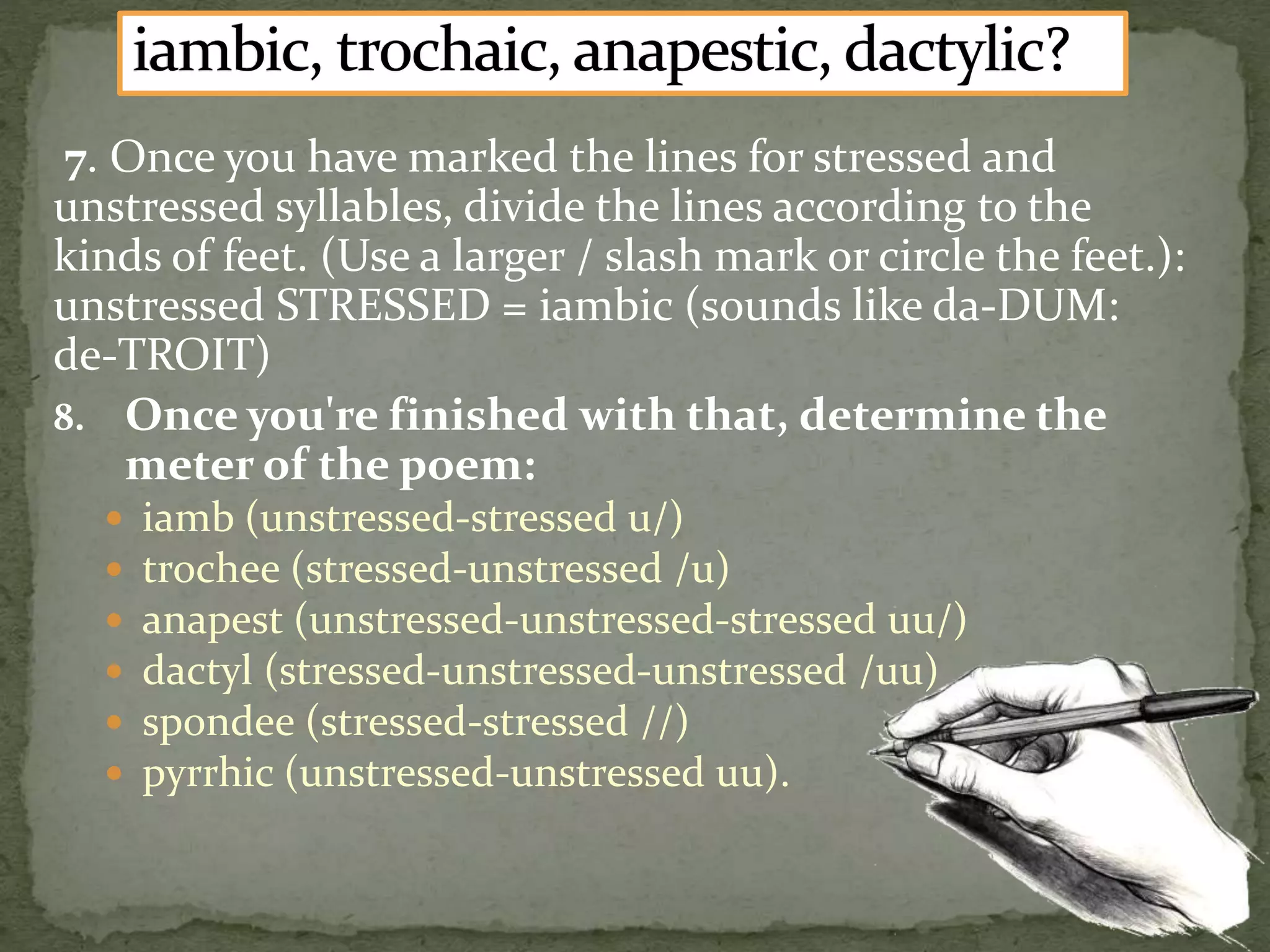

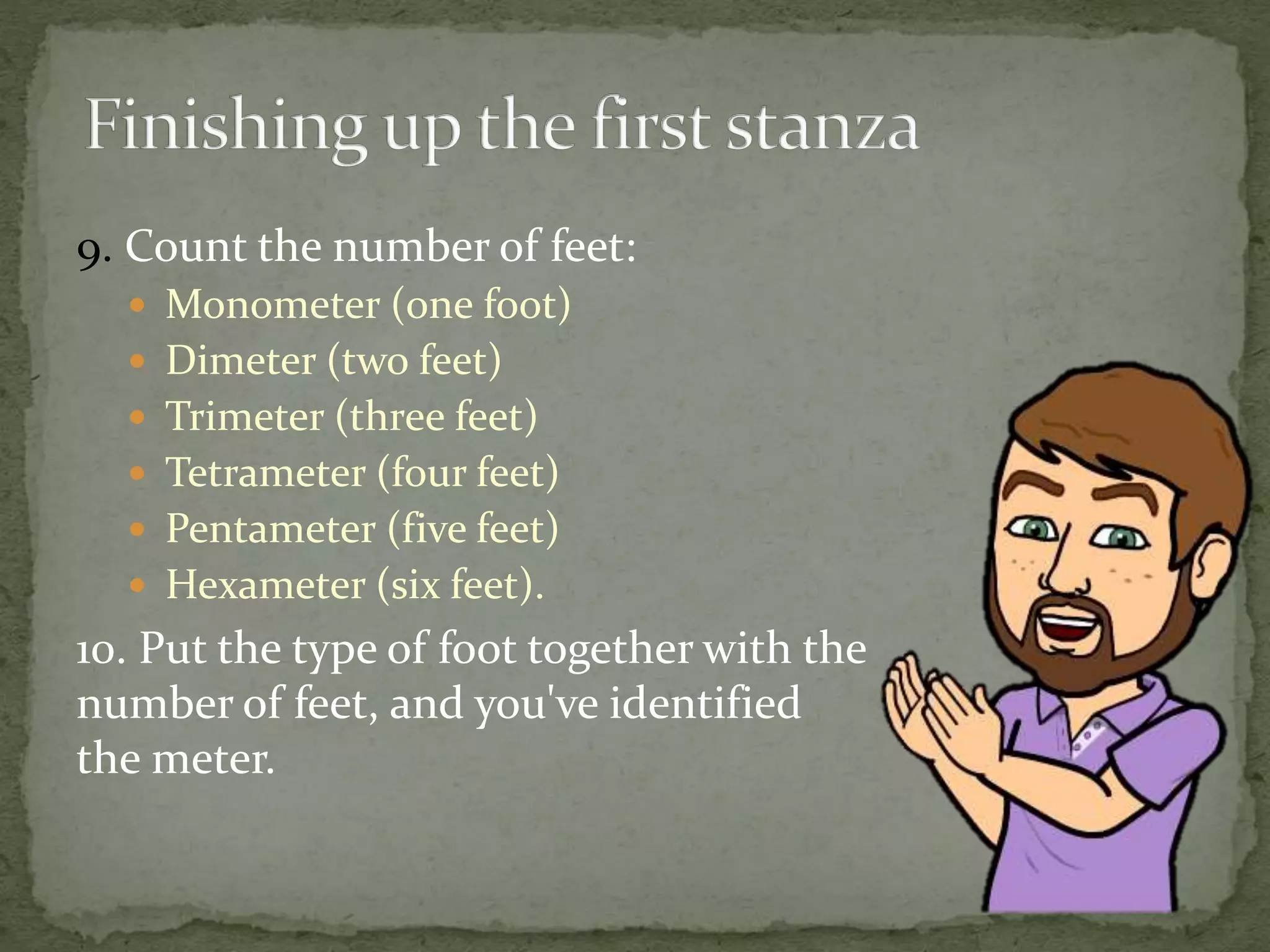

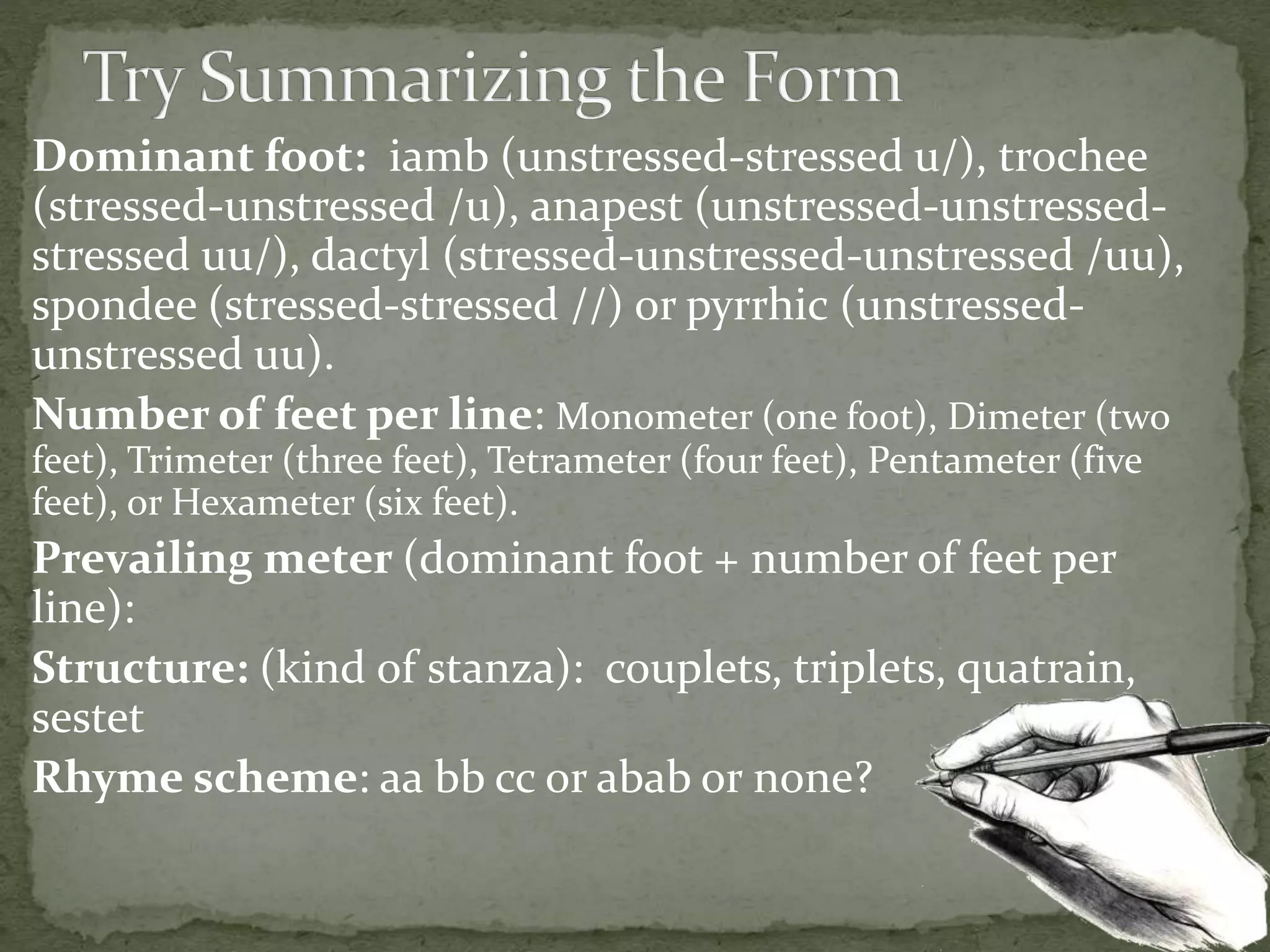

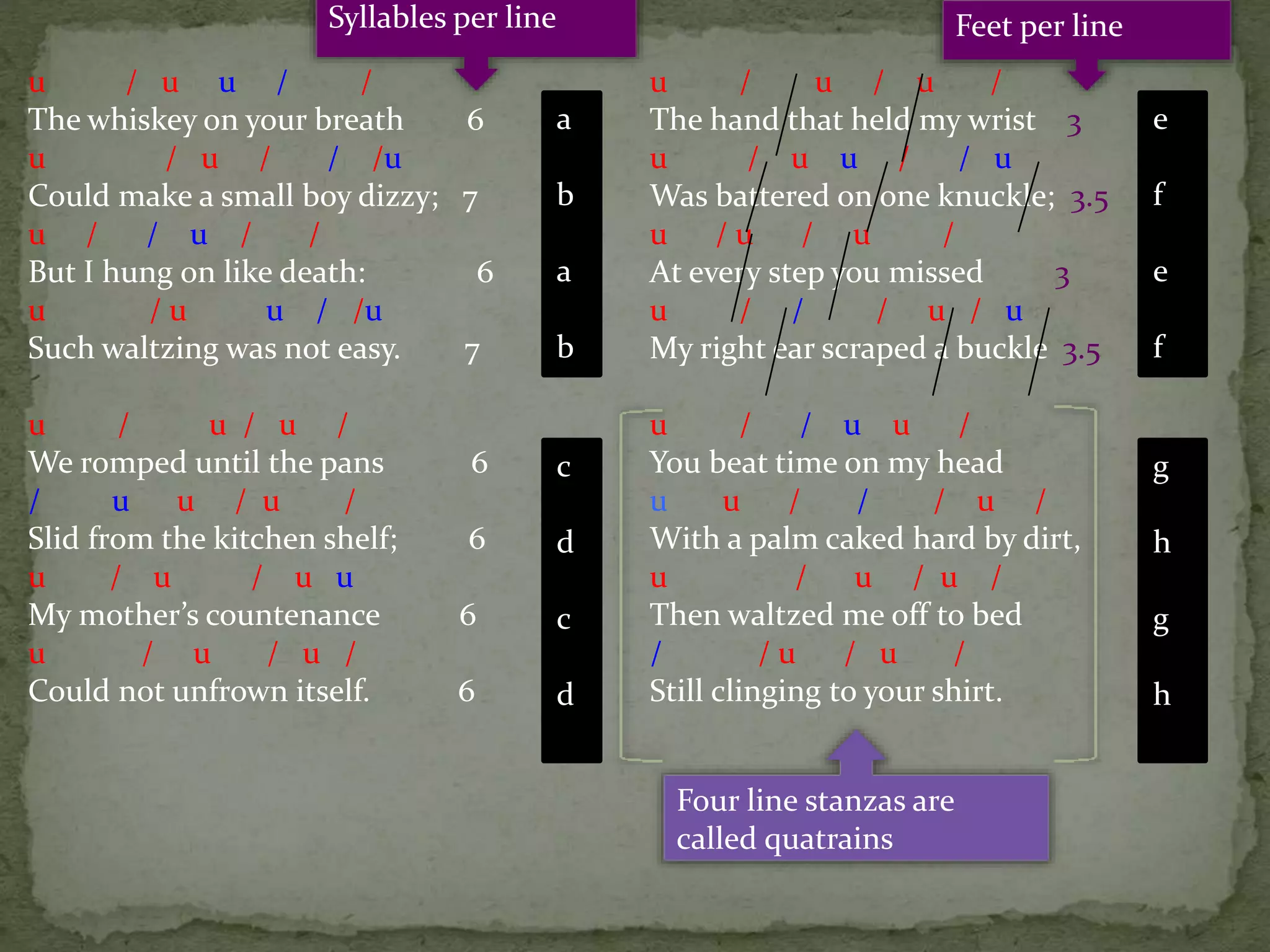

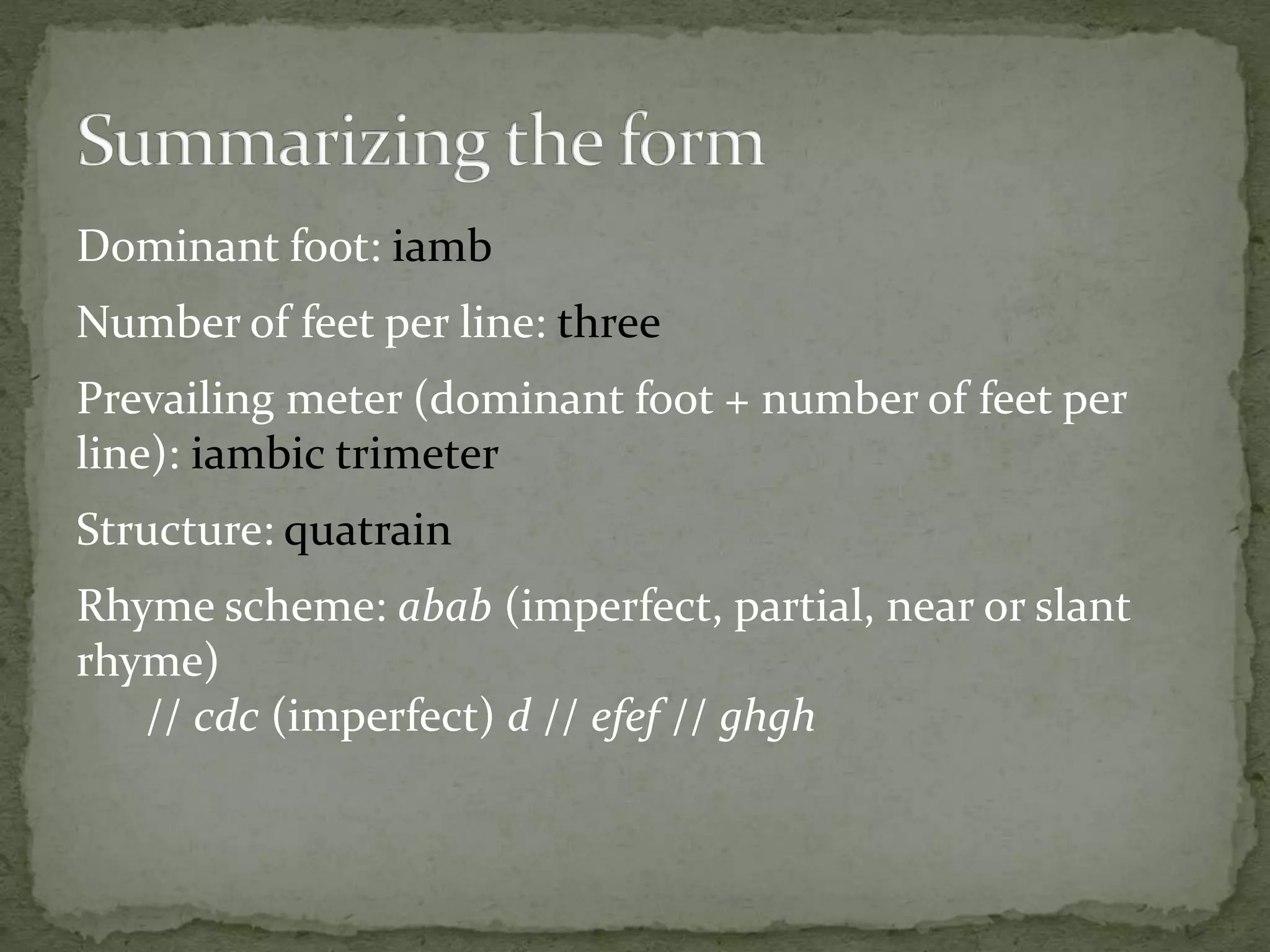

This document provides instruction on analyzing poetry through scansion and identifying formal elements. It begins with defining scansion as describing poetry's rhythms by dividing lines into feet and marking stressed and unstressed syllables. The document then provides a step-by-step process for scanning a poem, including reading it aloud, marking stresses, identifying the meter, counting feet, and determining the rhyme scheme. It analyzes Theodore Roethke's poem "My Papa's Waltz" as an example, identifying its iambic trimeter meter and abab rhyme scheme. Students are then assigned to scan and analyze the form of one additional poem.