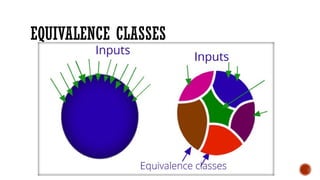

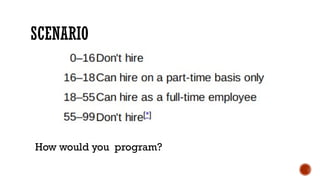

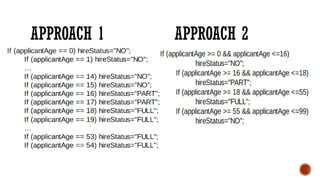

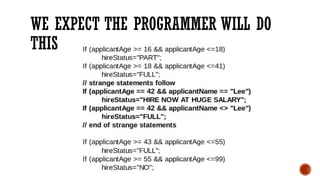

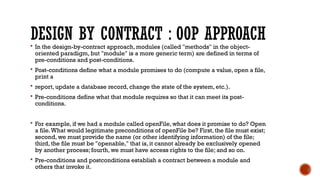

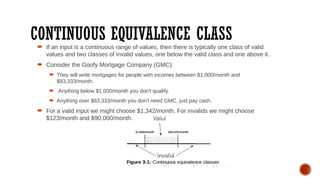

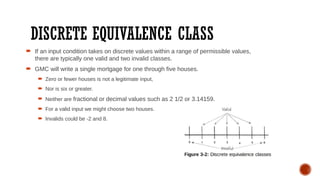

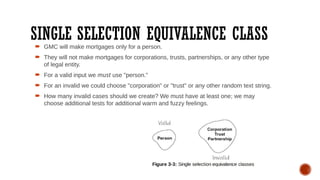

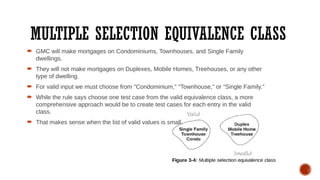

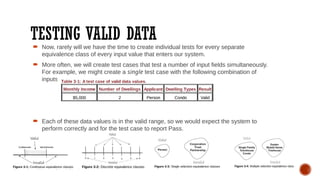

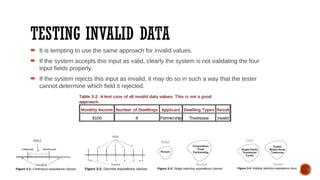

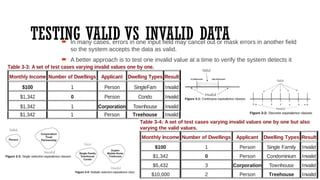

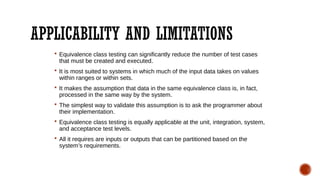

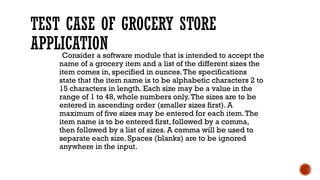

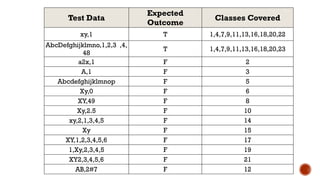

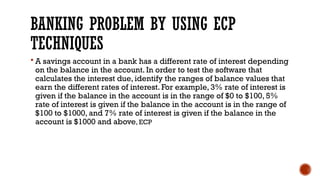

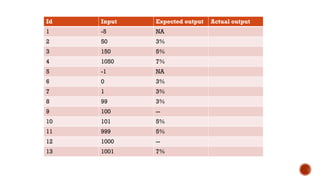

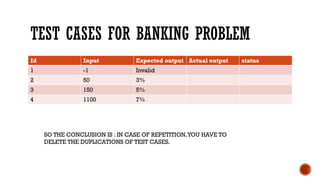

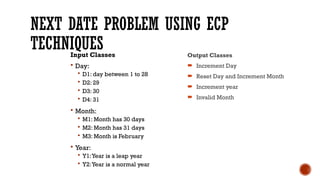

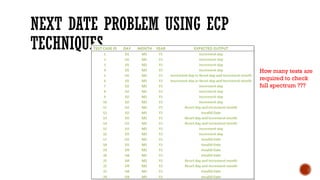

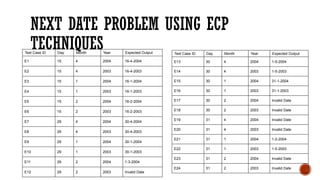

The document discusses software testing with a focus on equivalence class partitioning, outlining concepts like testing by contract, defensive design, and various types of equivalence classes. It provides examples of applications in grocery store and banking software to illustrate how to create test cases by identifying valid and invalid data inputs. Finally, it emphasizes the applicability, limitations, and methodologies involved in implementing equivalence class testing.