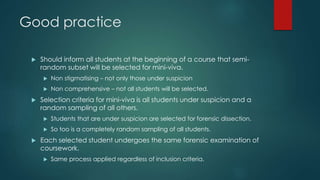

This document discusses the challenges of defining and identifying plagiarism in programming coursework submissions. It notes that software engineering best practices like code reuse and standard algorithms/patterns can conflict with academic definitions of plagiarism. It also examines ethics issues around methods for identifying plagiarism in code, and recommends as good practice notifying students of potential mini-vivas in advance and giving them access to annotated transcripts before misconduct hearings. The overall aim is to have a fair and balanced approach that considers the complexities of programming assignments and students' perspectives.