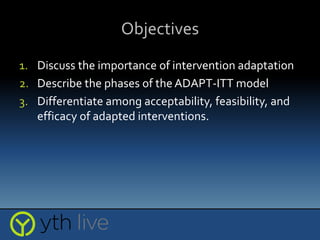

The document discusses the adaptation of evidence-based sexual health interventions for mobile health (mHealth) delivery by emphasizing the importance of intervention adaptation and presenting the adapt-ITT model phases. It highlights the effectiveness of text messaging for sexual health promotion among young adults, who prefer technology for learning and engagement, while noting the need for adaptations to cater to diverse populations. Key aspects of the adaptation process include acceptability, feasibility, and efficacy testing to ensure successful implementation of interventions.

![WhyText Messages?

• Young adults often prefer technologically-advanced

methods of learning and social engagement [1]

• Decreased organizational costs associated with

personnel and resources needed for intervention

implementation [2]

• Standardized text messages ensure the intervention

fidelity [2]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/01tiffanym-150512232451-lva1-app6891/85/Stop-Reinventing-the-Wheel-Adapting-Evidence-Based-Sexual-Health-Interventions-for-mHealth-Delivery-5-320.jpg)

![WhyText Messages? (cont.)

• Utilization of mHealth is encouraged by the CDC [3]

• Removes barriers to healthcare [2]

• Sexual health text messaging interventions have been

shown to be effective [4-7]

• Texts can be sent/received without a broadband

connection](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/01tiffanym-150512232451-lva1-app6891/85/Stop-Reinventing-the-Wheel-Adapting-Evidence-Based-Sexual-Health-Interventions-for-mHealth-Delivery-6-320.jpg)

![WhyText Messages? (cont.)

• 95% of young adults own a mobile phone [8]

• Not everyone owns a smartphone…

63% of women; 85% of young adults, ages 18-29; 70% of

Blacks [9]

• …But EVERYONE texts!!!

100% of young adult mobile phone owners engage in

texting [9]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/01tiffanym-150512232451-lva1-app6891/85/Stop-Reinventing-the-Wheel-Adapting-Evidence-Based-Sexual-Health-Interventions-for-mHealth-Delivery-7-320.jpg)

![Why Adaptation?

• Adoption = ready to implement “as is”

• Adaptation = changing an established intervention

for implementation among a population of a

different age, ethnicity, gender, etc.

• Instead of creating entirely new interventions,

adaptation of effective interventions is

recommended [10-15]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/01tiffanym-150512232451-lva1-app6891/85/Stop-Reinventing-the-Wheel-Adapting-Evidence-Based-Sexual-Health-Interventions-for-mHealth-Delivery-8-320.jpg)

![The ADAPT-ITT Model

• Created by HIV/STD prevention interventionists,

Wingood and DiClemente, whose SiSTA

intervention has been successfully adapted for

various populations [16-21]

• Emphasizes acceptability, feasibility, and efficacy

testing](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/01tiffanym-150512232451-lva1-app6891/85/Stop-Reinventing-the-Wheel-Adapting-Evidence-Based-Sexual-Health-Interventions-for-mHealth-Delivery-9-320.jpg)