The document discusses instruction set architectures (ISAs) and how programs are represented and executed at the machine level. It covers several key topics:

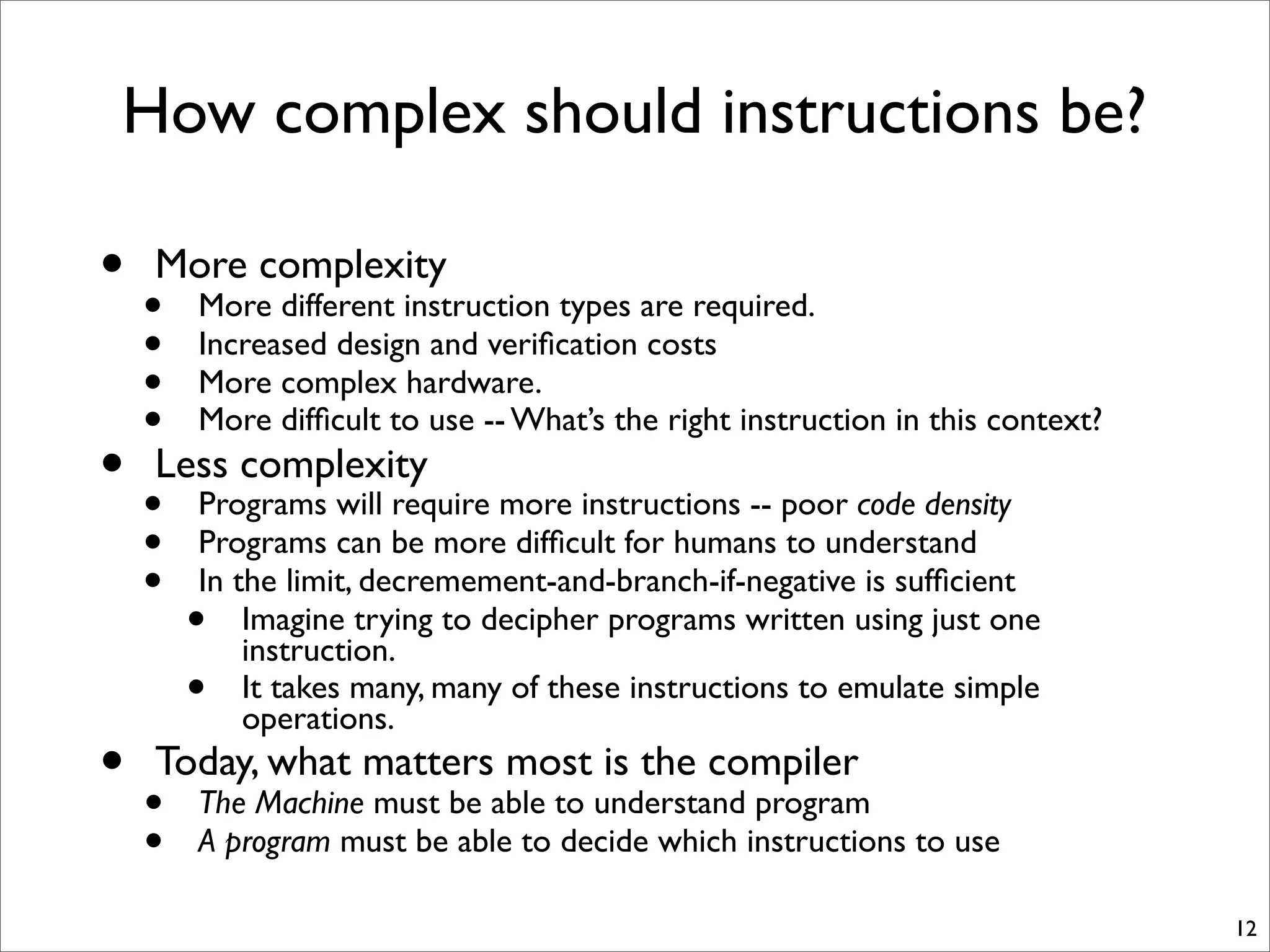

- Representing programs as sequences of instructions that the computer can interpret. Instructions need to be defined along with the architectural state the computer operates on.

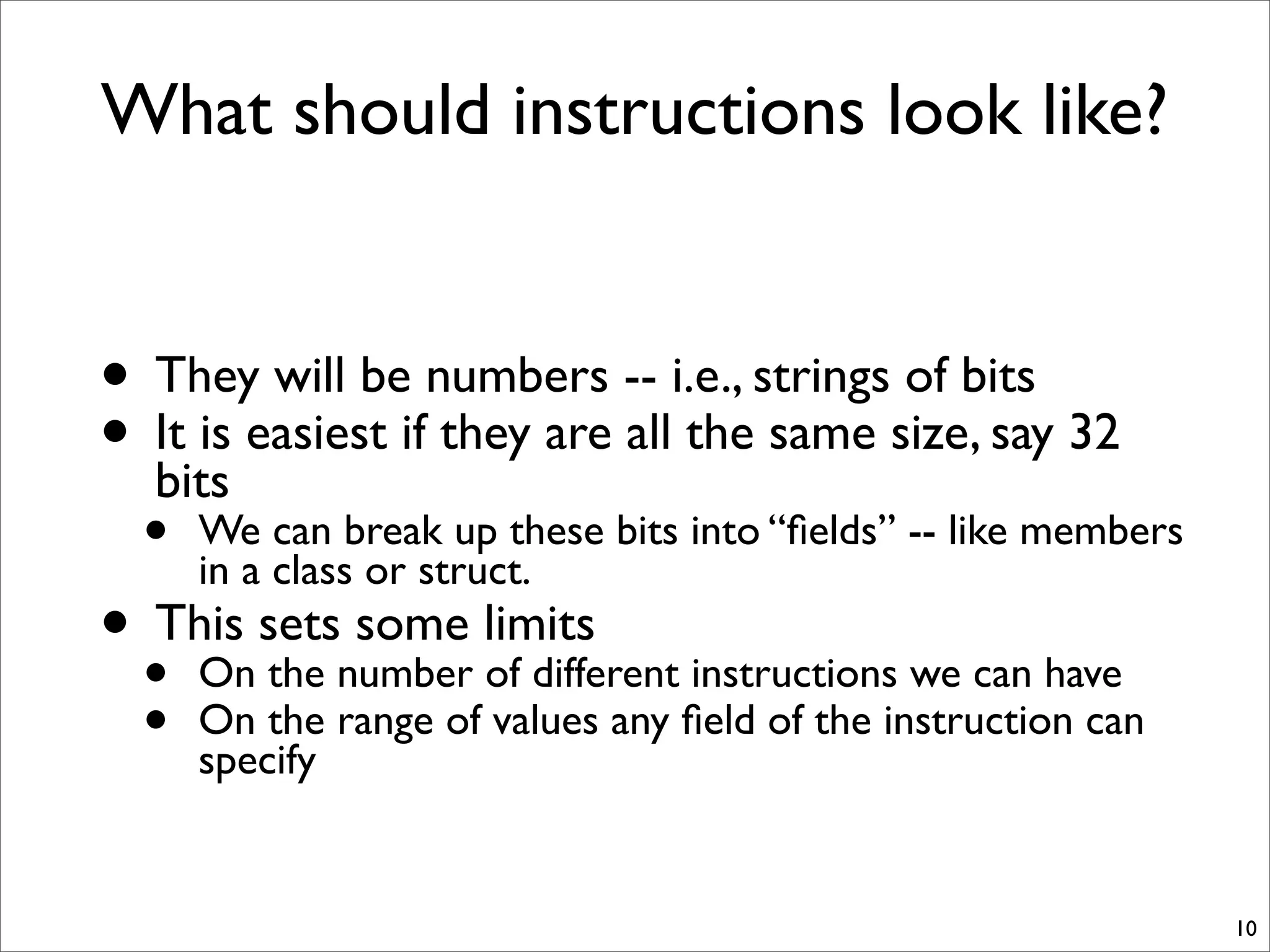

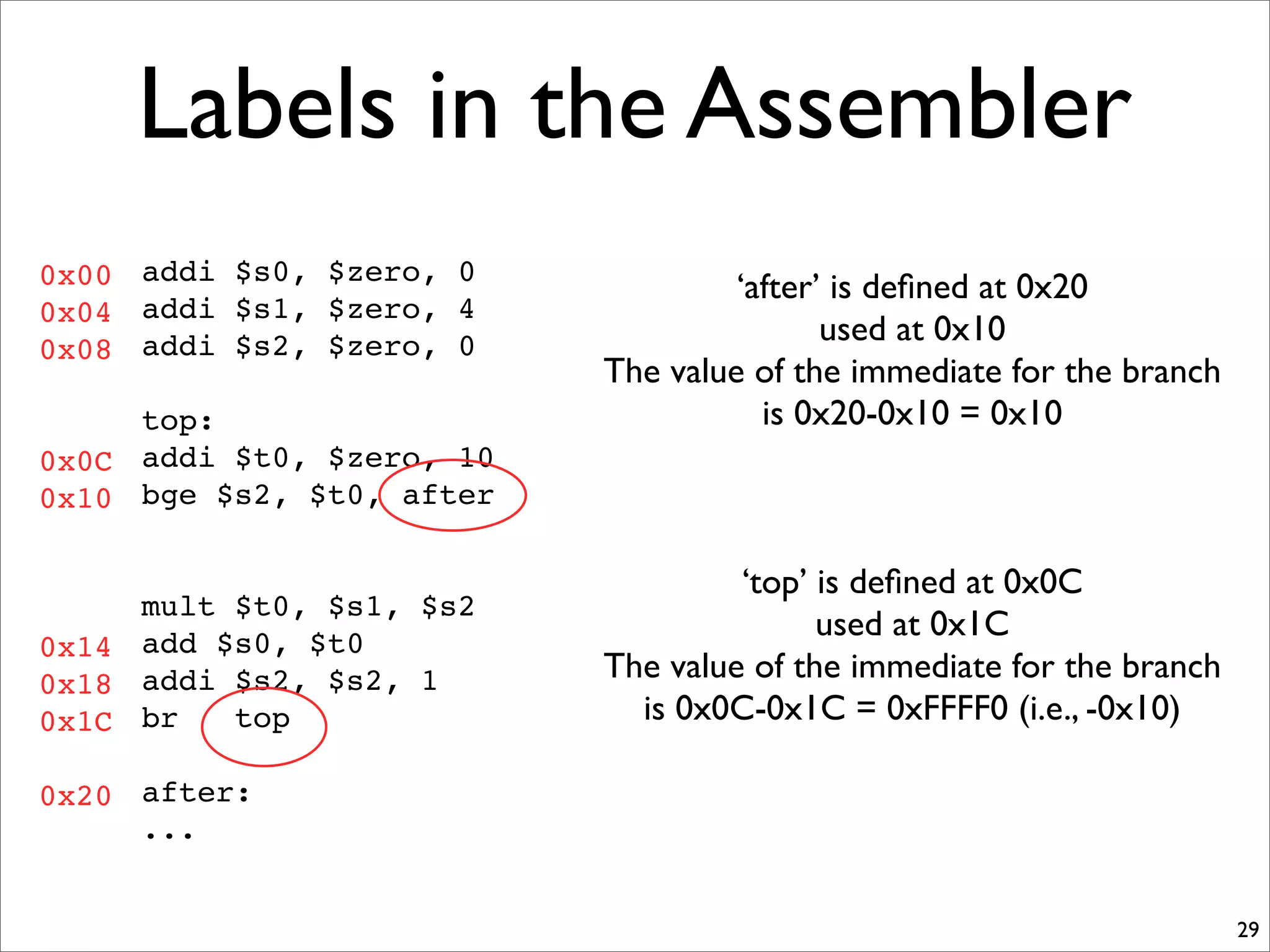

- The basic components of program execution, including fetching instructions from memory, decoding them, fetching operands, executing the computation, and storing results.

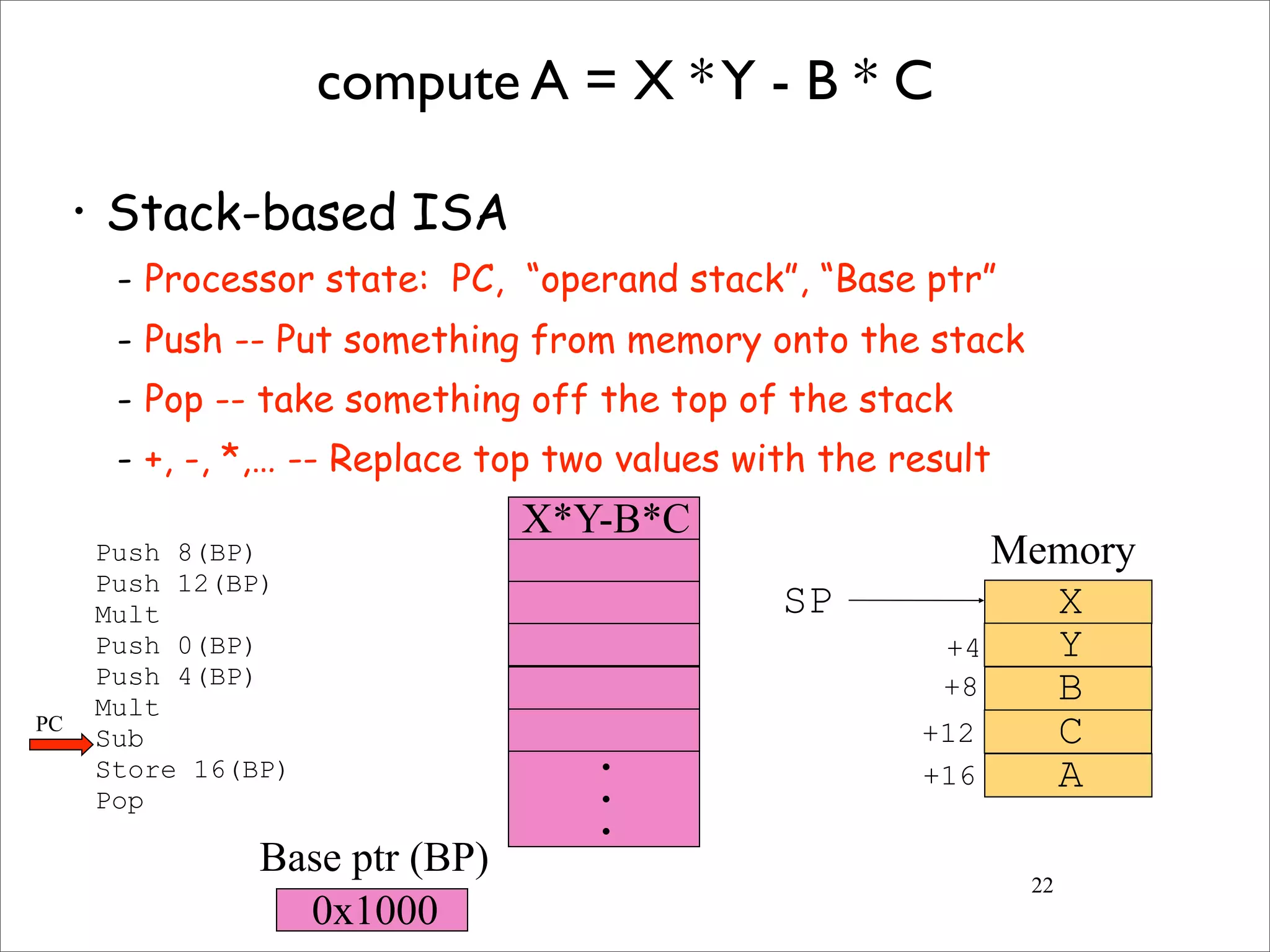

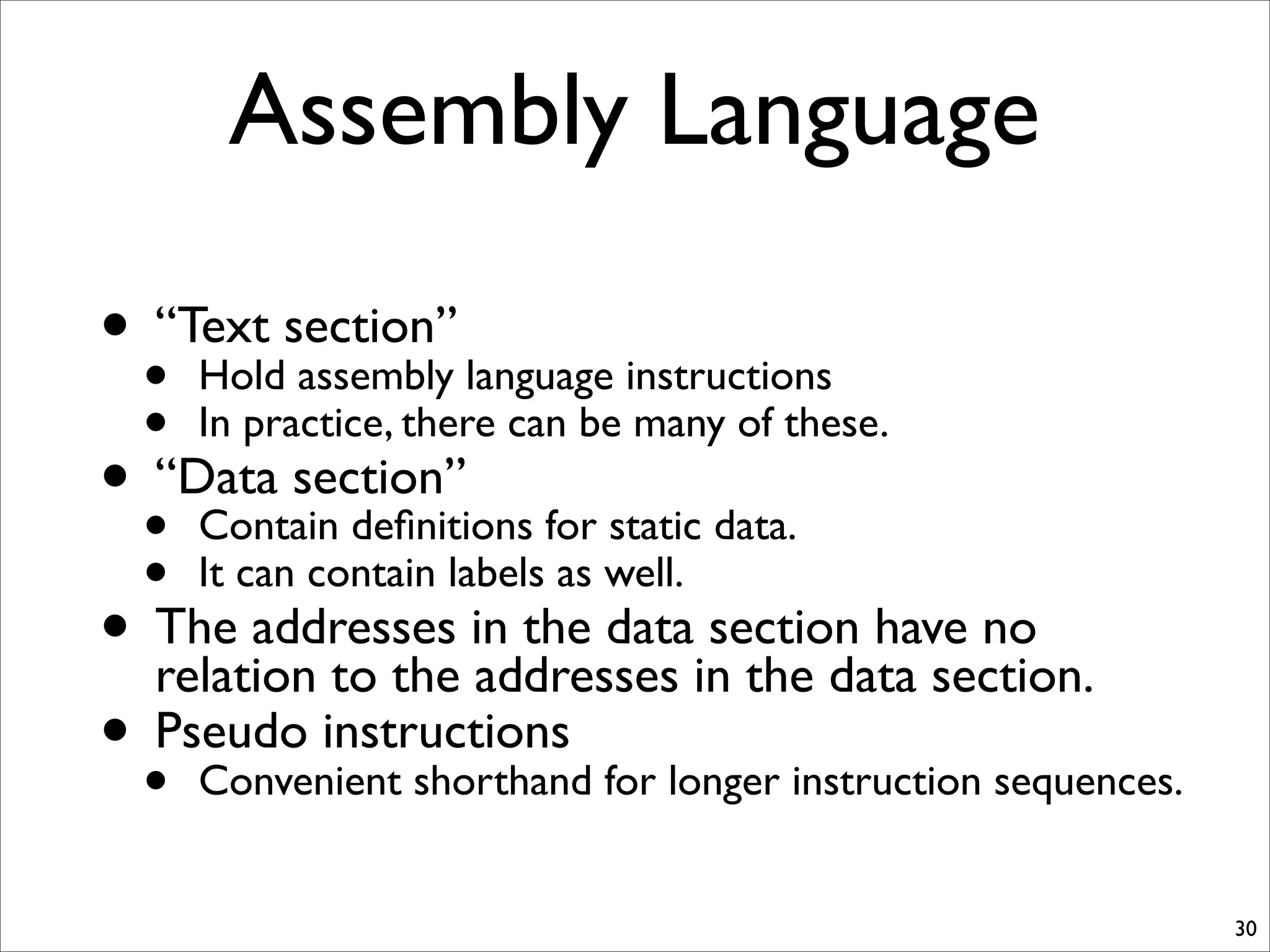

- Factors in designing instructions like choosing operations, representation as fixed-size numbers, and balancing complexity.

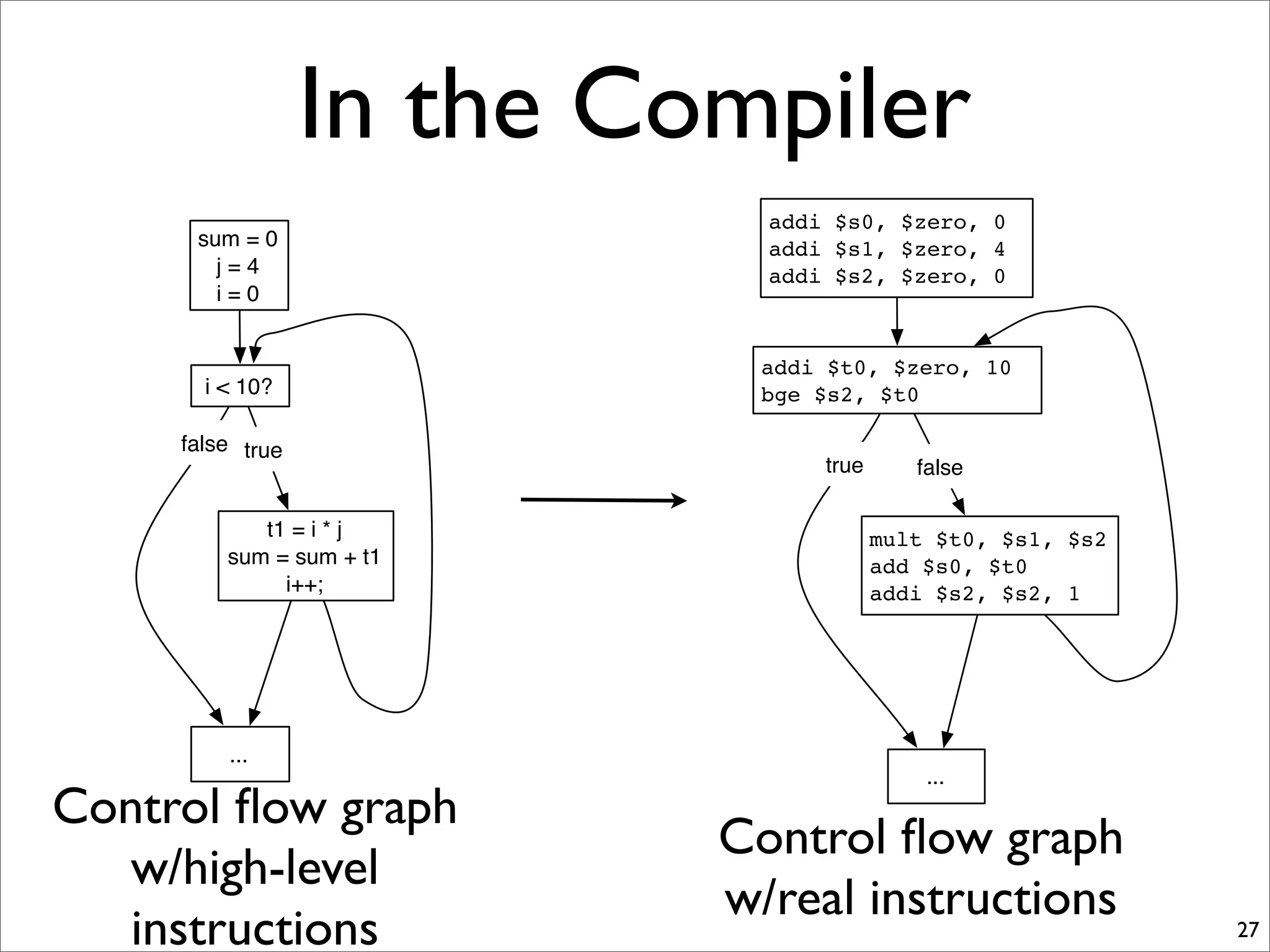

- How high-level programs are translated through compilers and assemblers into machine code that the processor can directly execute.

![Program Execution

7

Instruction

Fetch

Instruction

Decode

Operand

Fetch

Execute

Result

Store

Next

Instruction

Read instruction from program storage (mem[PC])

Determine required actions and instruction size

Locate and obtain operand data

Compute result value

Deposit results in storage for later use

Determine successor instruction (i.e. compute next PC).

Usually this mean PC = PC + <instruction size in bytes>

• This is the algorithm for a stored-program

computer

• The Program Counter (PC) is the key](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/01isa-150725190038-lva1-app6892/75/01-isa-7-2048.jpg)

![Motivating Code segments

• a = b + c;

• a = b + c + d;

• a = b & c;

• a = b + 4;

• a = b - (c * (d/2) - 4);

• if (a) b = c;

• if (a == 4) b = c;

• while (a != 0) a--;

• a = 0xDEADBEEF;

• a = foo[4];

• foo[4] = a;

• a = foo.bar;

• a = a + b + c + d +... +z;

• a = foo(b); -- next class

8](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/01isa-150725190038-lva1-app6892/75/01-isa-8-2048.jpg)