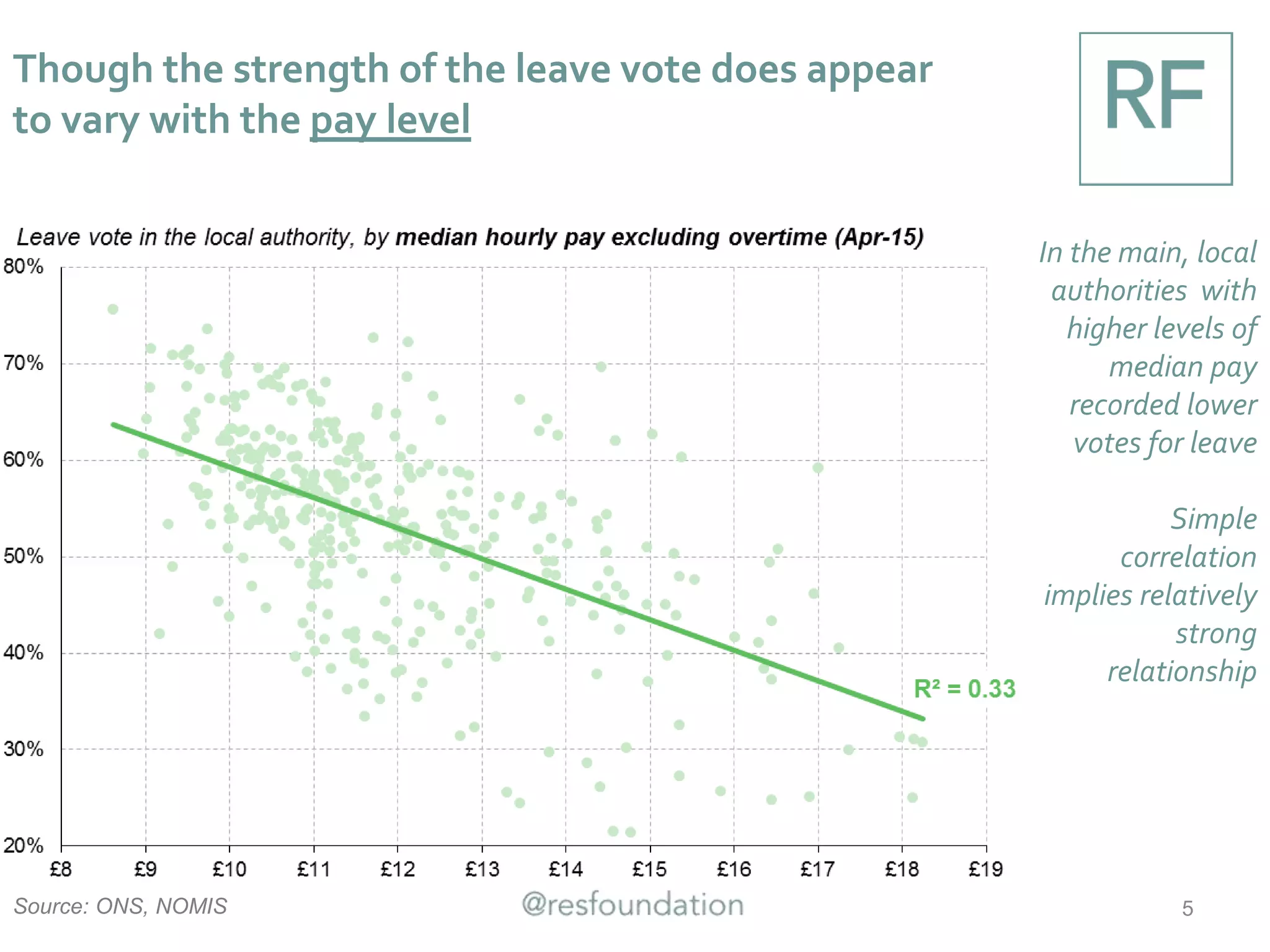

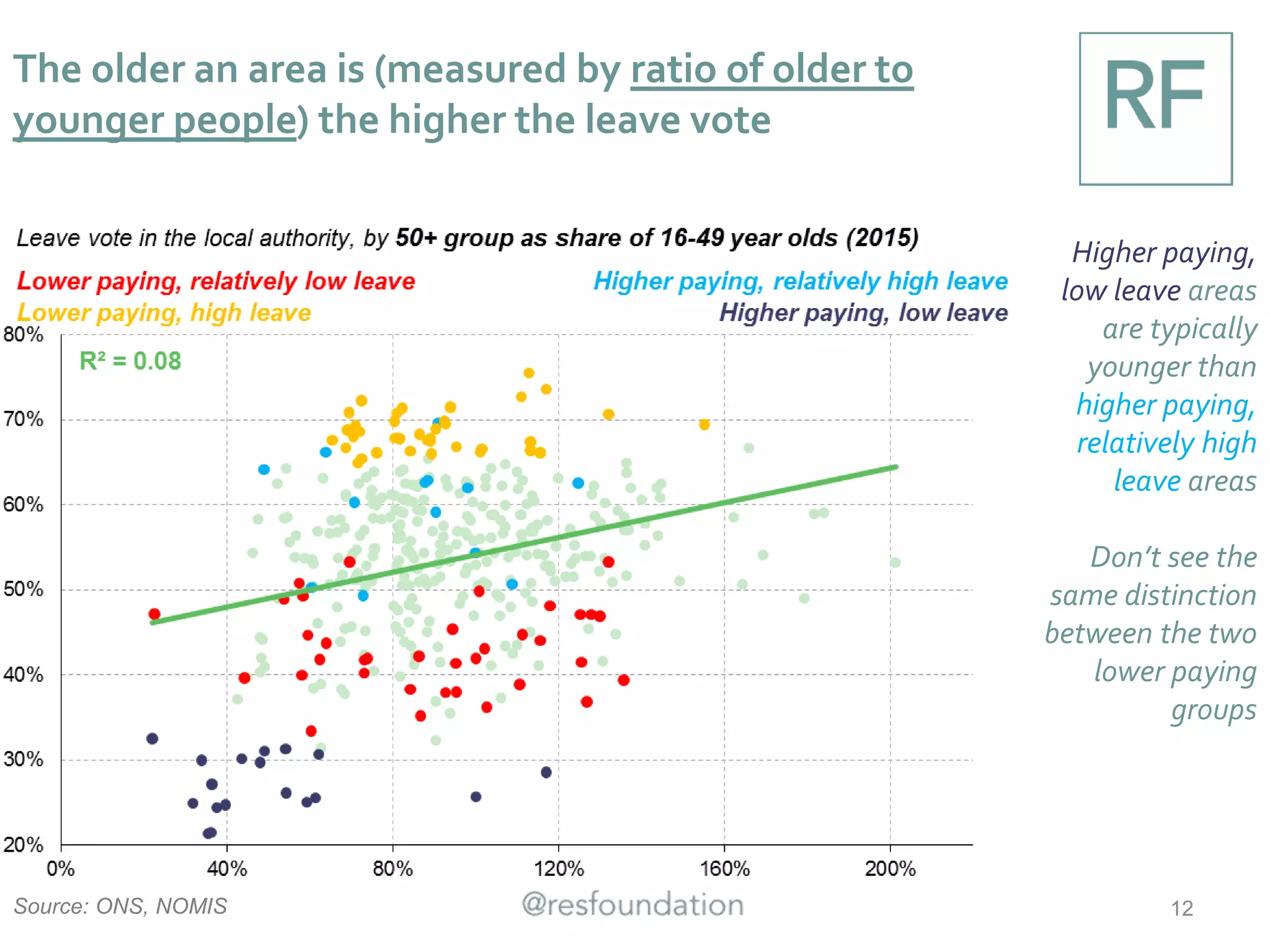

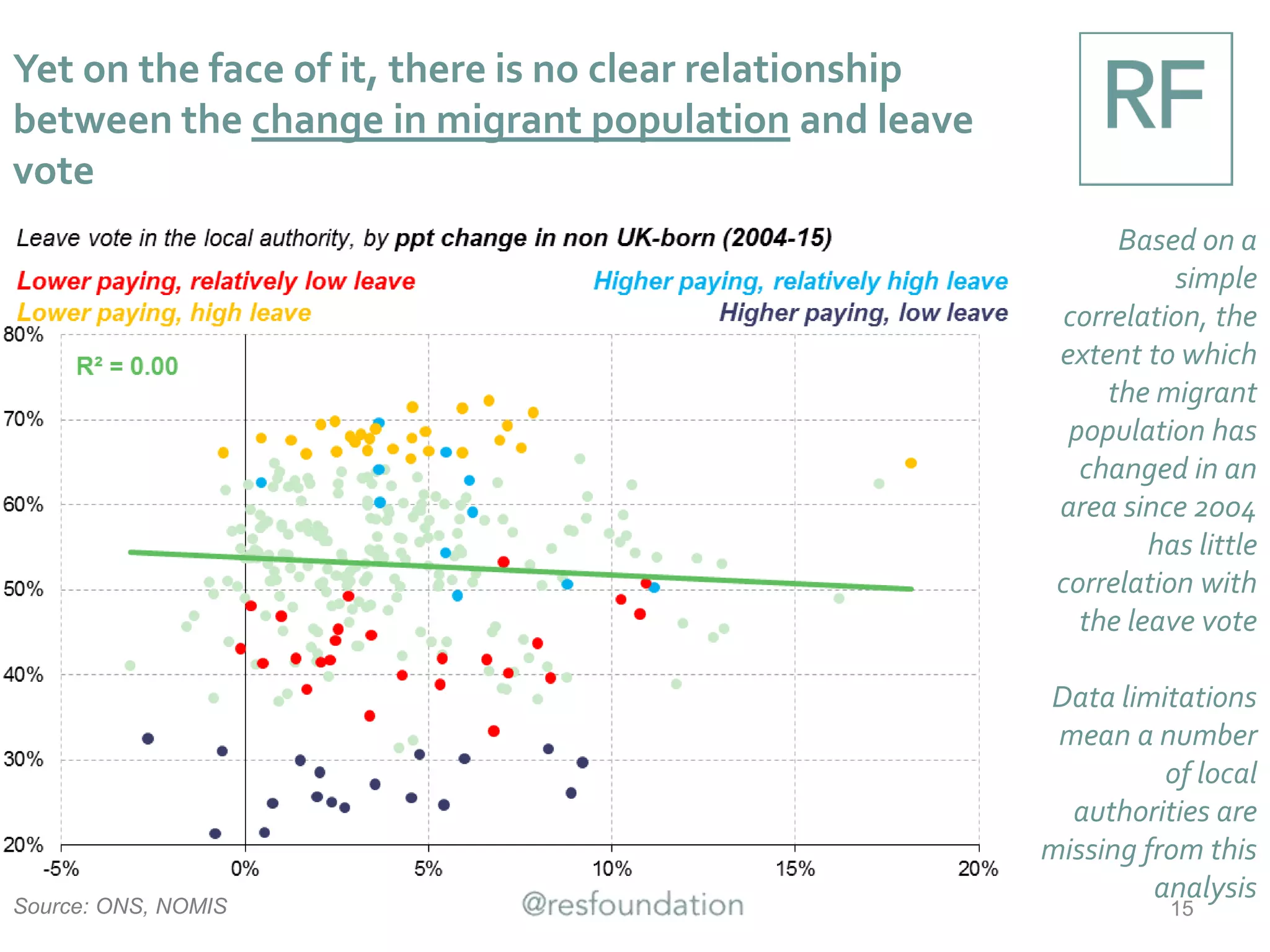

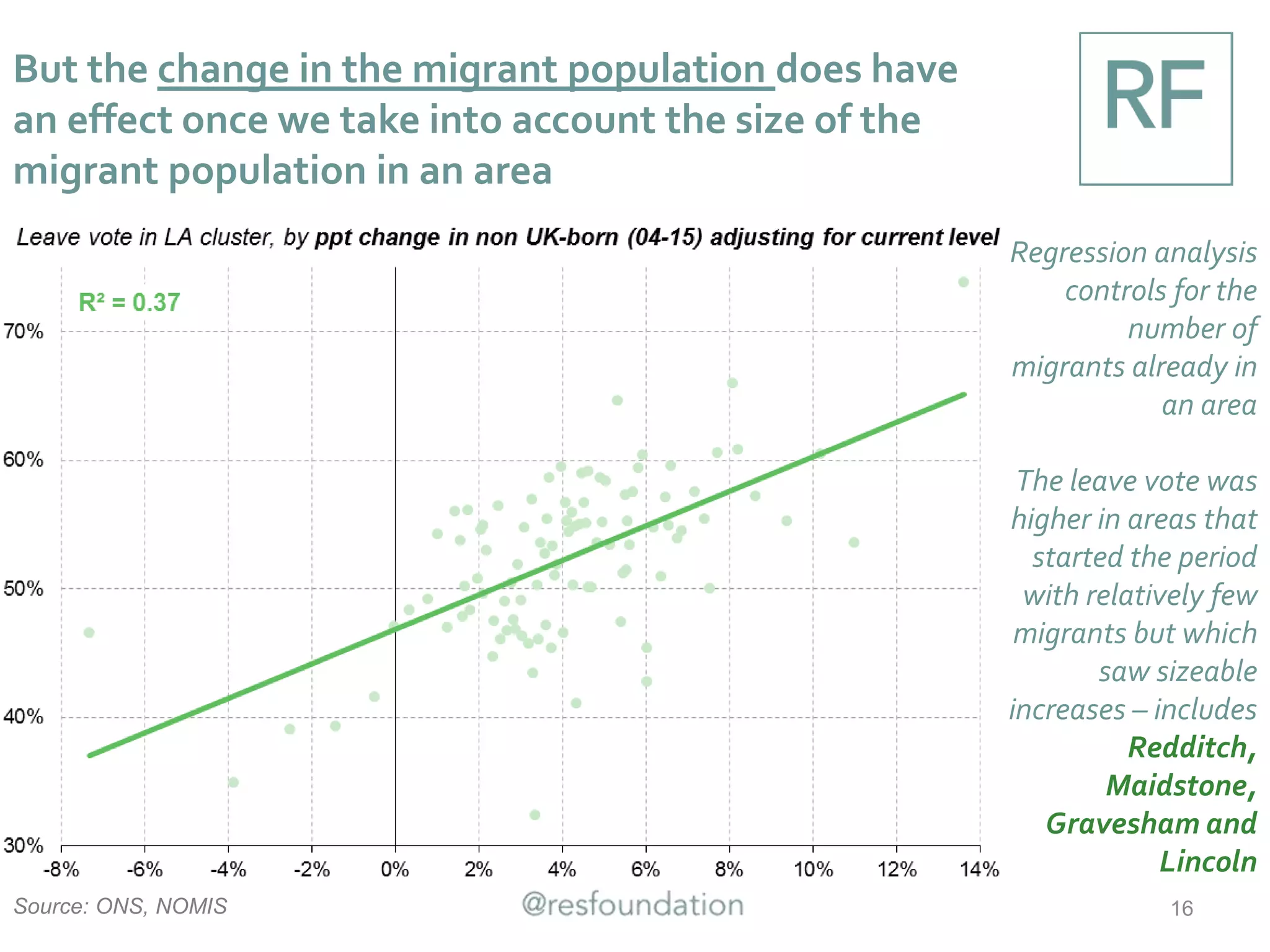

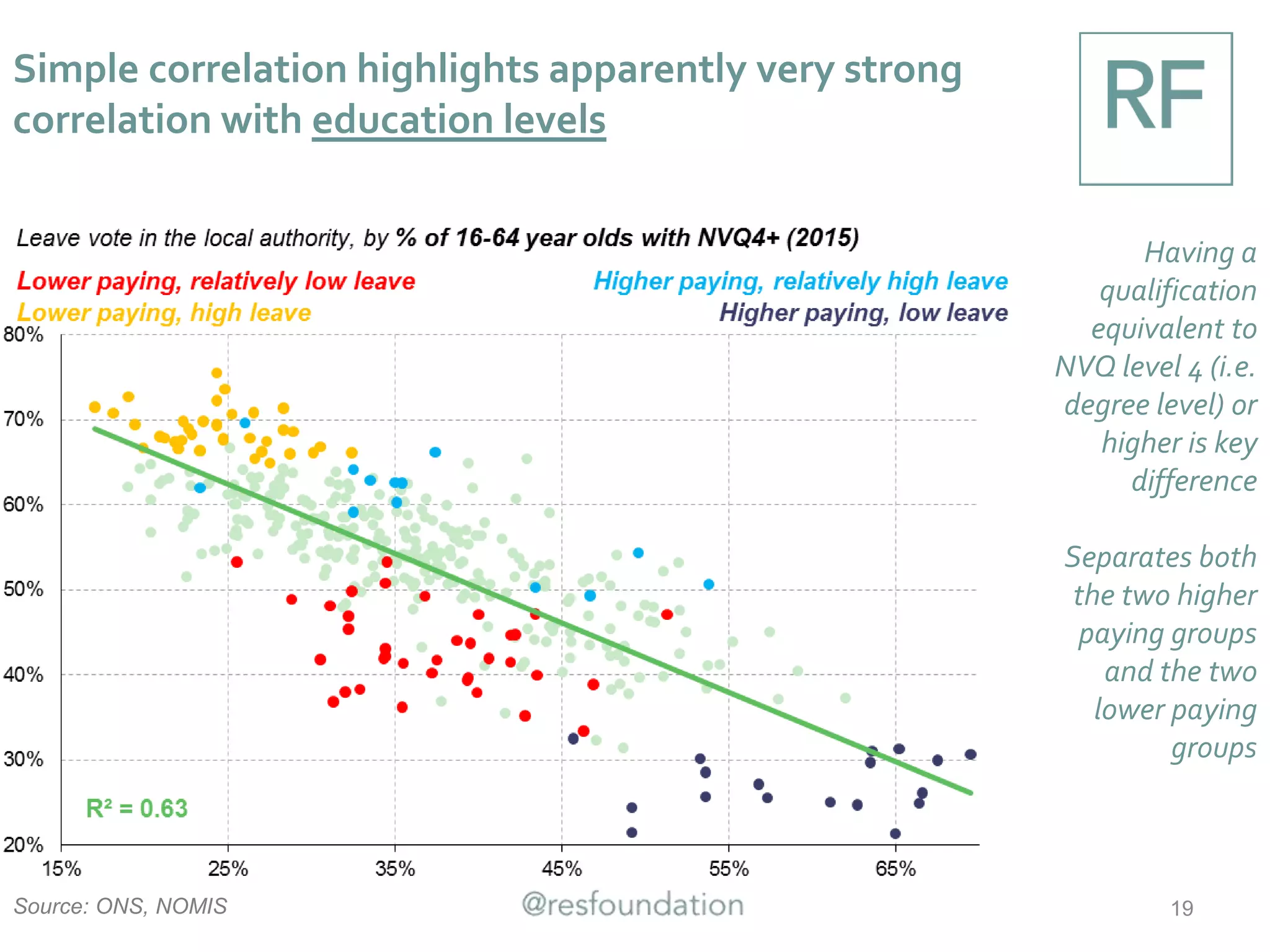

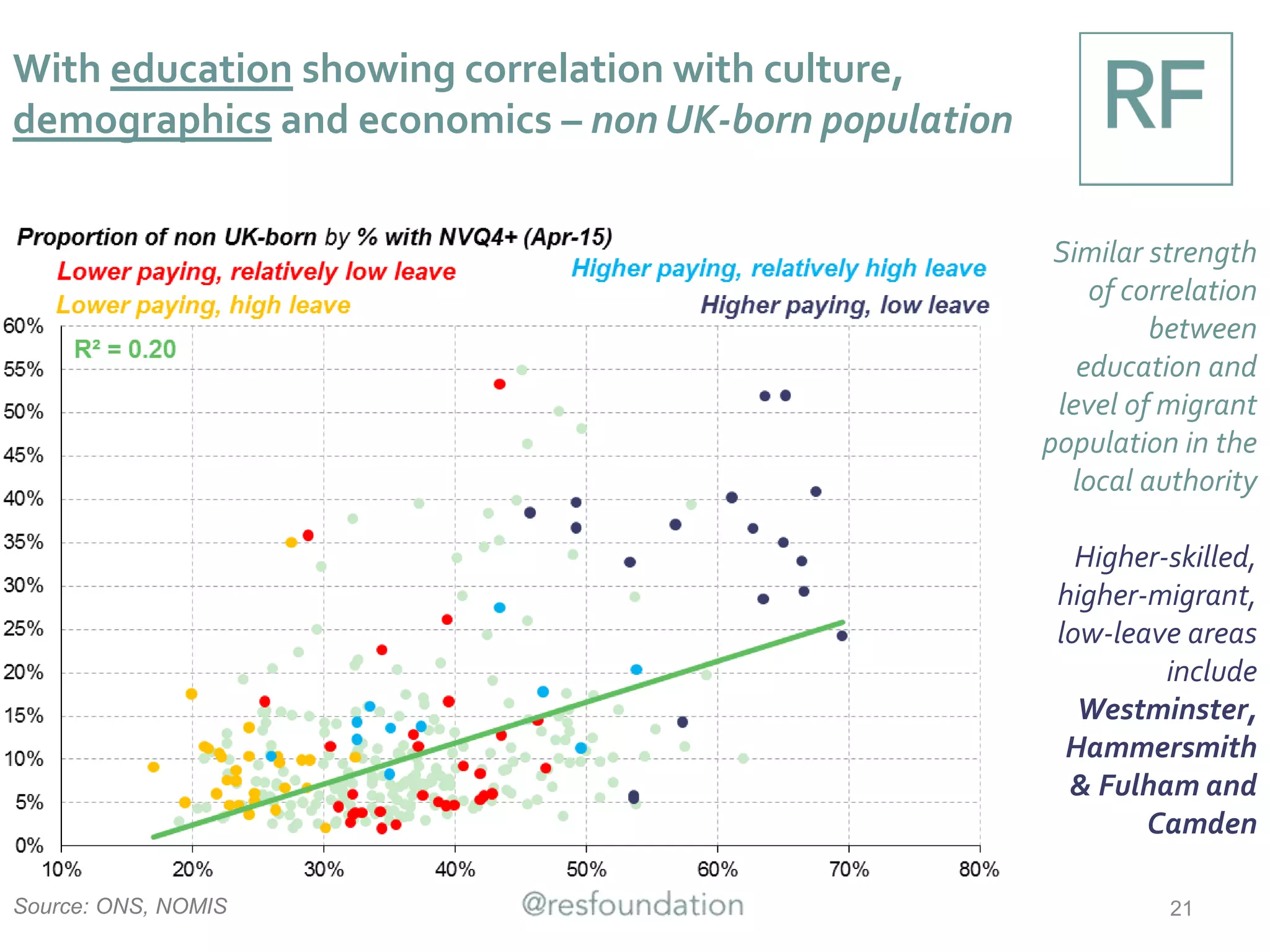

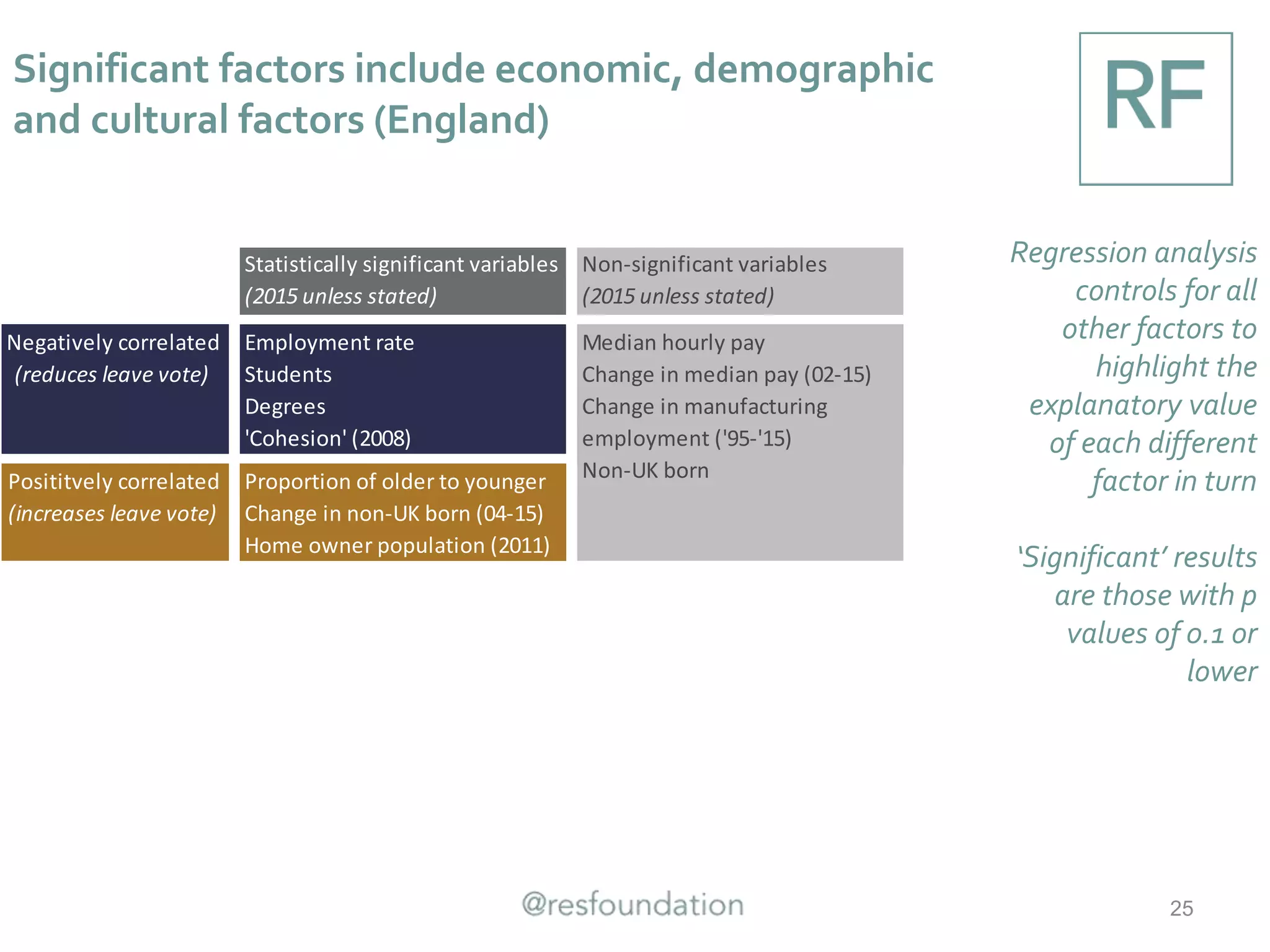

The document analyzes the factors influencing the Brexit vote across various local authorities in the UK, emphasizing the significance of geography, demographics, economics, and culture. It utilizes regression models to identify relationships between these factors and voting patterns, revealing that local economic conditions, levels of education, and community cohesion notably affected voting behavior. The analysis concludes that while economic factors are important, demographic and cultural aspects are equally critical in understanding the voting trends.