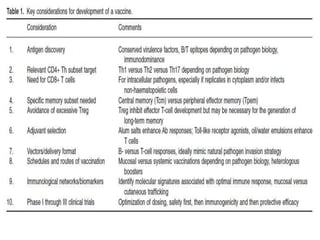

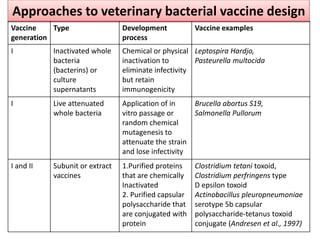

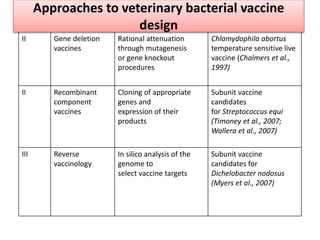

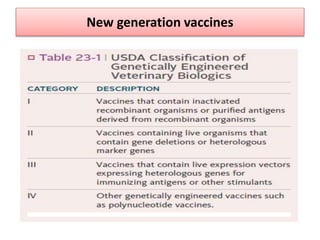

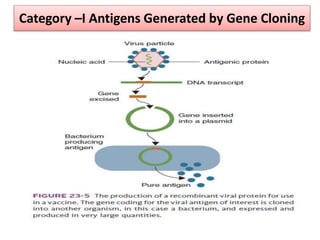

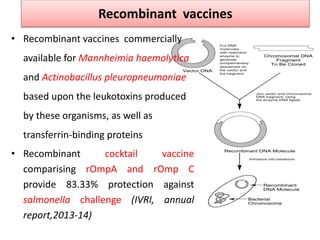

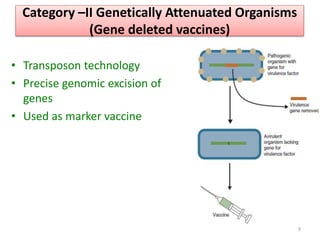

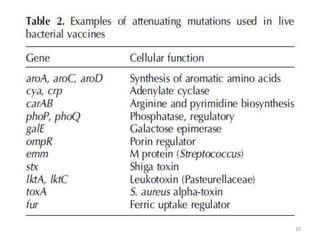

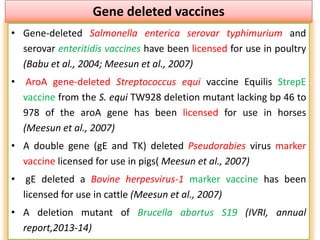

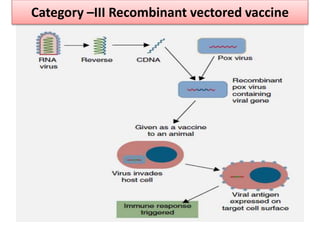

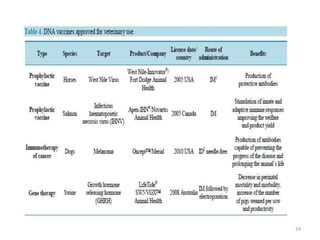

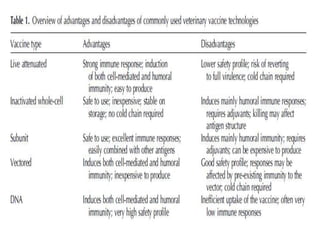

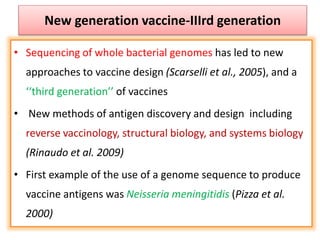

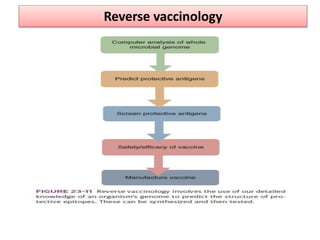

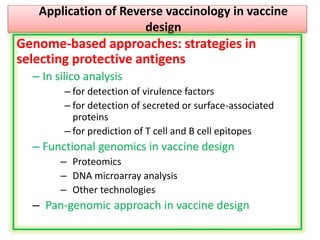

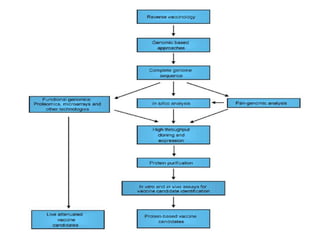

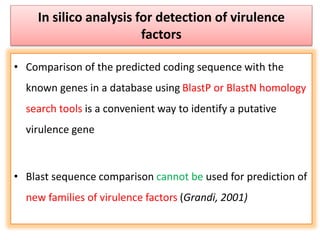

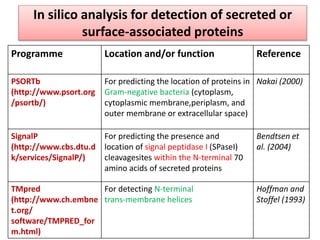

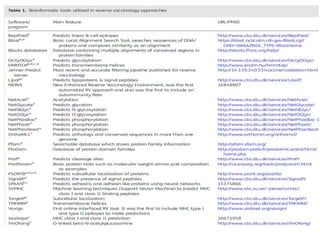

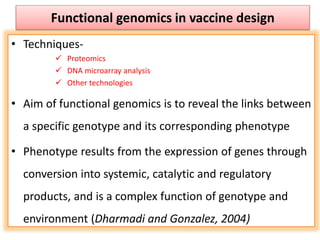

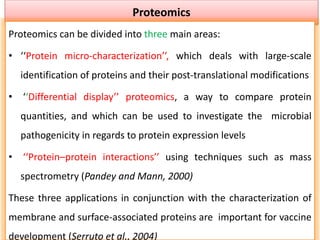

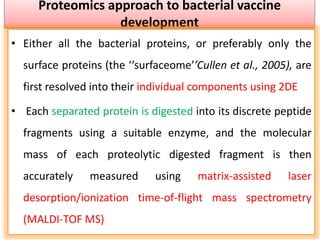

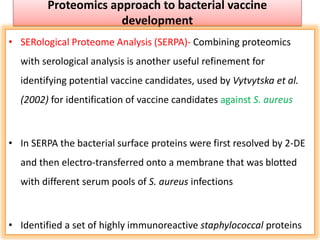

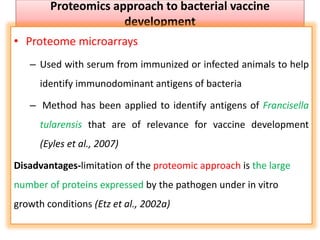

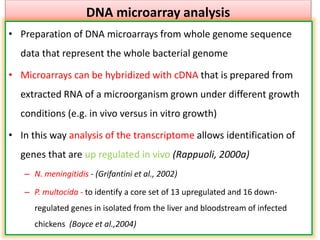

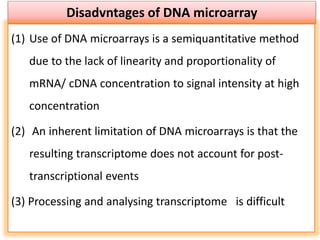

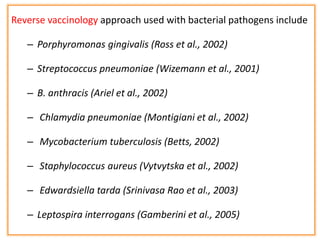

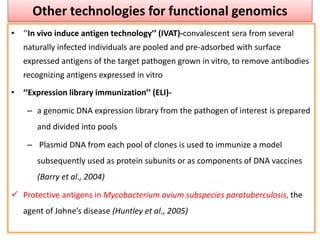

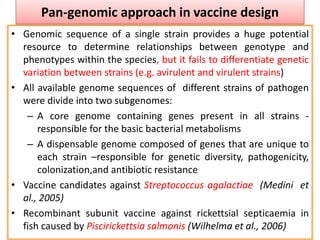

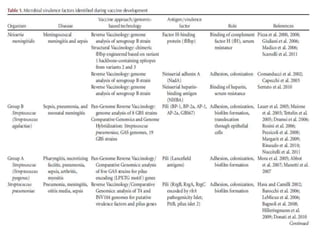

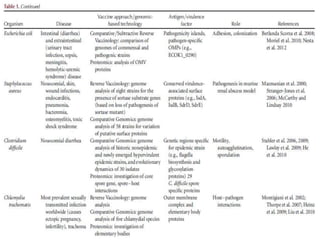

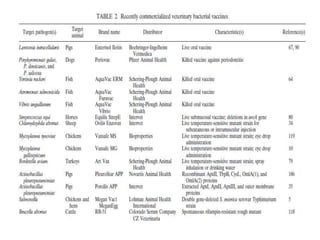

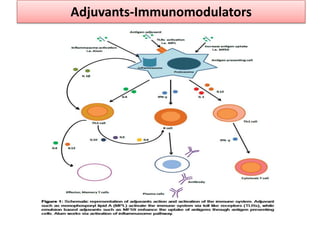

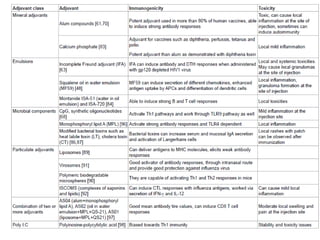

The document discusses various approaches to veterinary bacterial vaccine design, detailing different types of vaccines such as inactivated, live attenuated, subunit, and gene deletion vaccines. It highlights the development of third-generation vaccines through advanced methods like reverse vaccinology and functional genomics, aiming for improved efficacy and reduced cold-storage requirements. The conclusion emphasizes the need for modern techniques to enhance vaccine stability and effectiveness in controlling animal diseases and thereby benefiting human health.