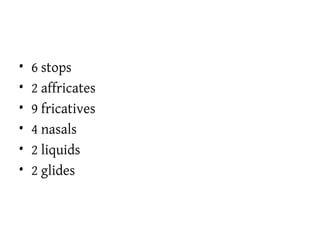

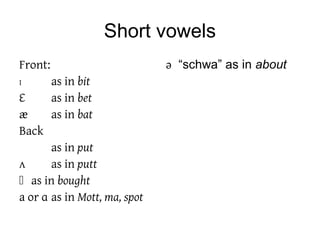

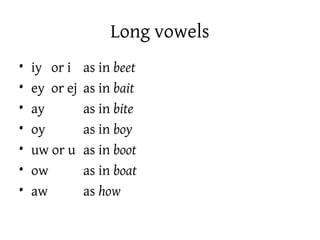

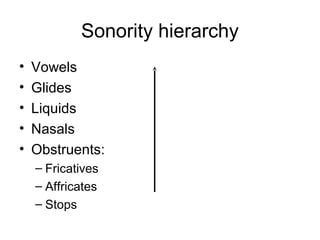

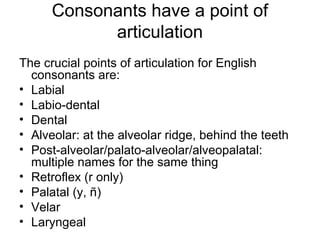

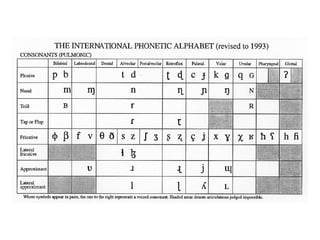

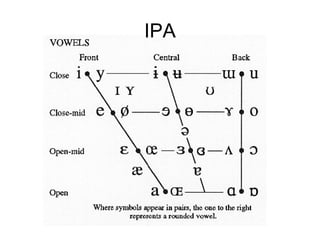

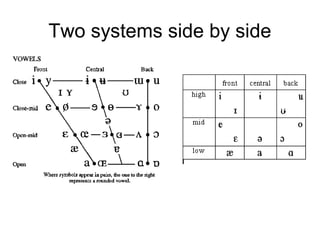

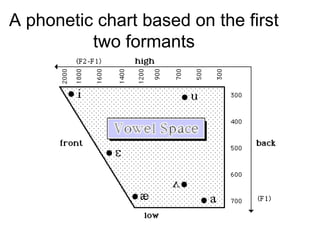

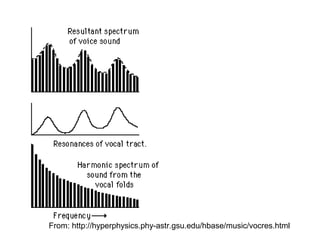

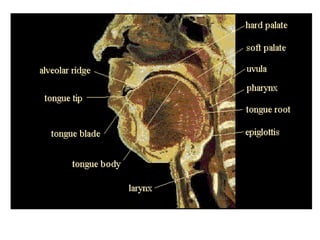

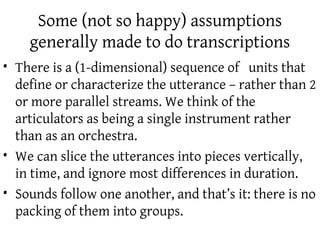

This document provides an overview of phonetics and phonetic transcription. It discusses the main subfields of phonetics including articulatory, acoustic, and perceptual phonetics. It describes the articulatory apparatus and assumptions made in transcription. It then provides examples of consonants and vowels in English, categorizing them based on their place and manner of articulation. It notes some key points about phonological analysis and variation in sound production across contexts and speakers.

![Sounds of English

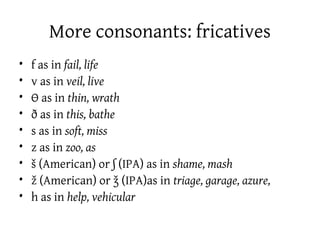

Consonants: first, the stops:

• b as in bat, sob, cubby

• d as in date, hid, ado

• g as in gas, lag, ragged

• p as in pet, tap, repeat

• t as in tap, pet, attack

• k as in king, pick, picking

When we need to emphasize

that we are using a phonetic

transcription, we put square

brackets [b] around the symbols.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/consonantsandvowels-130725024558-phpapp01/85/Consonants-andvowels-6-320.jpg)