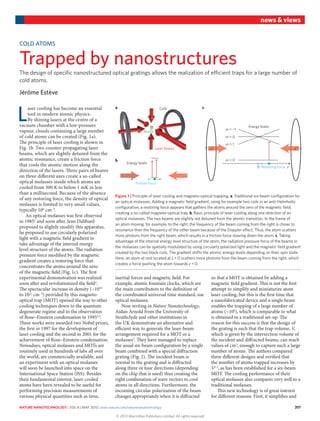

1) Laser cooling uses lasers to cool atoms to very low temperatures, creating clouds of cold atoms. It involves using counter-propagating laser beams slightly detuned from the atomic resonance to create friction and cool atomic motion.

2) In 1985, an optical molasses was first observed, cooling atoms to below 1 mK. However, optical molasses have low density due to the lack of a restoring force. Jean Dalibard then proposed using polarized light and a magnetic field gradient to create a restoring force in a magneto-optical trap (MOT), greatly increasing atom density.

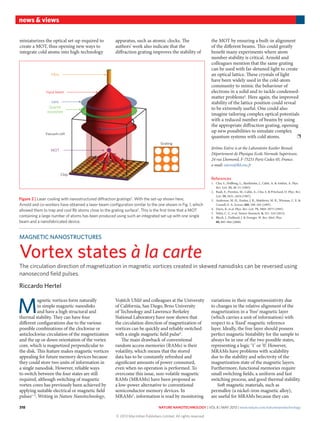

3) Now, researchers have demonstrated an efficient way to generate the laser beam configuration for a MOT or molasses using a