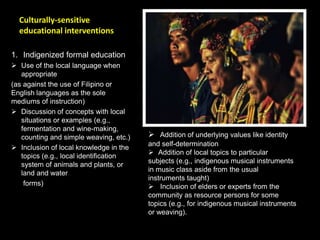

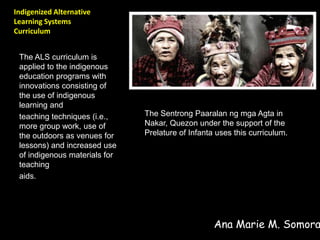

The document discusses indigenous education systems in the Philippines. It notes that the Philippines has over 100 indigenous communities totaling around 15-20 million people. While the communities vary in culture and heritage, they share experiences of discrimination. It also discusses the Indigenous Peoples Rights Act of 1997 which recognizes indigenous rights. The document then examines historical interventions in indigenous education and their impacts, as well as culturally sensitive approaches like incorporating local languages and knowledge. It describes key aspects of indigenous education systems, including curriculum, teaching methods, and evaluating learning. The conclusion emphasizes the importance of culture and affirming indigenous identity and knowledge systems in education.