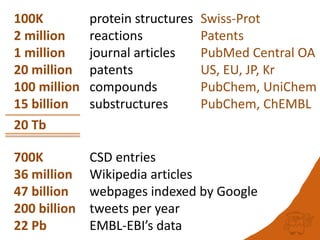

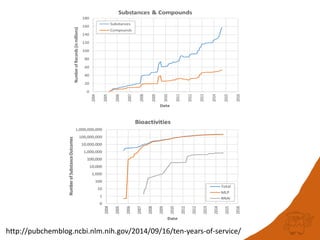

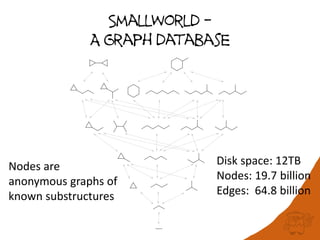

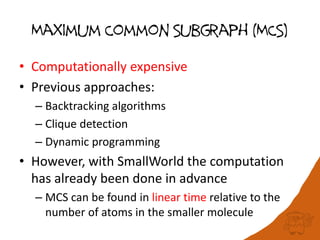

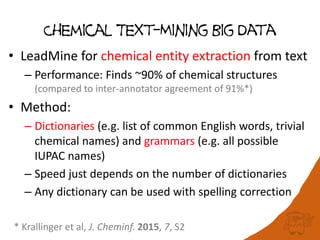

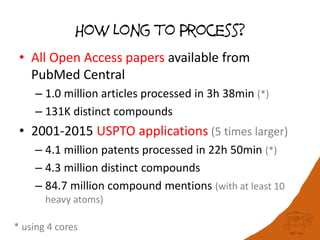

100 million compounds, 100K protein structures, 2 million reactions, 1 million journal articles, 20 million patents and 15 billion substructures. Is 20TB really Big Data? With modern hardware and efficient algorithms, many classic cheminformatics problems can be handled with today’s datasets. Noel O’Boyle, Daniel Lowe, John May and Roger Sayle of NextMove Software discuss how traditional cheminformatics tasks can be performed on large chemical datasets through techniques like precomputing substructures, optimised substructure searching, and graph databases.

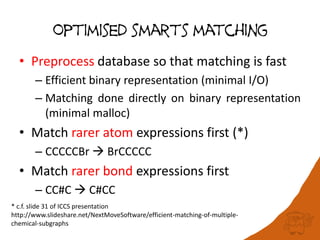

![Big Data is…

“…a broad term for data sets so large or complex

that traditional data processing applications are

inadequate.” [Wikipedia]

Any dataset could be considered Big Data

without sufficiently efficient algorithms and

tools](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/rscapr2015bigdata-150423041734-conversion-gate02/85/Is-20TB-really-Big-Data-2-320.jpg)

![Performance

• Scales with the number of SMARTS patterns

used

– currently 802 patterns for 504 reactions

• Test set: 1.1 million reactions extracted from

the USPTO applications 2001-2012

– Processed in 11.2 h

– 437 K reactions named

US20010000038A1 : 3.10.2 Friedel-Crafts alkylation [Friedel-

Crafts reaction]

US20010000038A1 : 10.1.5 Wohl-Ziegler bromination

[Halogenation]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/rscapr2015bigdata-150423041734-conversion-gate02/85/Is-20TB-really-Big-Data-21-320.jpg)

[C@@H](C(=O)NCC(=O)N[C@@H](CCCCN)C(=O)N1CCC[C@H]1C(=O)N[C@@H](CO)C(=O)N[C@@H](Cc2c[nH]cn2)C(=

O)N3CCC[C@H]3C(=O)N[C@@H](CO)C(=O)N[C@@H](CCC(=O)O)C(=O)N4CCC[C@H]4C(=O)N[C@@H](C(C)C)C(=O)N[C@@H](CC(

C)C)C(=O)N[C@@H](C)C(=O)N[C@@H]([C@@H](C)CC)C(=O)N[C@@H](CC(=O)O)C(=O)N[C@@H](C)C(=O)N[C@@H](CS)C(=O)N[

C@@H](CCC(=O)O)C(=O)N5CCC[C@H]5C(=O)N6CCC[C@H]6C(=O)N[C@@H](CCCNC(=N)N)C(=O)N[C@@H](CC(=O)N)C(=O)N[C@

@H](C(C)C)C(=O)N[C@@H](CCCNC(=N)N)C(=O)N[C@@H]([C@@H](C)CC)C(=O)N[C@@H]([C@@H](C)O)C(=O)N[C@@H](CC(=O)

O)C(=O)N[C@@H]([C@@H](C)CC)C(=O)N[C@@H](CO)C(=O)N[C@@H](CCCCN)C(=O)N[C@@H](CC(=O)N)C(=O)N[C@@H](CO)C(=

O)N[C@@H](C(C)C)C(=O)N[C@@H](CC(=O)N)C(=O)N[C@@H](CC(C)C)C(=O)N[C@@H](CO)C(=O)N[C@@H](Cc7c[nH]c8c7cccc8)C(

=O)N[C@@H](CCC(=O)N)C(=O)N[C@@H](CCC(=O)N)C(=O)N9CCC[C@H]9C(=O)N[C@@H](C)C(=O)N[C@@H](Cc1ccccc1)C(=O)N[

C@@H](CC(=O)O)C(=O)NCC(=O)NCC(=O)N[C@@H](CO)C(=O)N[C@@H](CCCCN)C(=O)N[C@@H]([C@@H](C)CC)C(=O)N[C@@H](

[C@@H](C)O)C(=O)NCC(=O)N[C@@H](Cc1ccc(cc1)O)C(=O)N[C@@H]([C@@H](C)CC)C(=O)N[C@@H](C(C)C)C(=O)N[C@@H](CCC

(=O)O)C(=O)N[C@@H](CCCNC(=N)N)C(=O)N[C@@H](CCCNC(=N)N)C(=O)N[C@@H](CC(=O)O)C(=O)N[C@@H](CC(C)C)C(=O)N1C

CC[C@H]1C(=O)N[C@@H](CC(=O)O)C(=O)NCC(=O)N[C@@H](CCCNC(=N)N)C(=O)N[C@@H](Cc1c[nH]c2c1cccc2)C(=O)N[C@@H](

[C@@H](C)O)C(=O)N[C@@H](CCCCN)C(=O)N[C@@H](C)C(=O)N[C@@H](CO)C(=O)N[C@@H](Cc1ccccc1)C(=O)N[C@@H]([C@@H

](C)O)C(=O)N[C@@H](CC(=O)N)C(=O)N[C@@H](C(C)C)C(=O)N[C@@H]([C@@H](C)CC)C(=O)N[C@@H](CCC(=O)O)C(=O)N[C@@

H]([C@@H](C)O)C(=O)N[C@@H](CCC(=O)N)C(=O)N[C@@H](Cc1ccccc1)C(=O)N[C@@H]([C@@H](C)O)C(=O)N[C@@H](C(C)C)C(

=O)N[C@@H](CO)C(=O)NCC(=O)N[C@@H](CC(C)C)C(=O)N[C@@H]([C@@H](C)O)C(=O)N[C@@H](CCC(=O)N)C(=O)N[C@@H](CC

(=O)N)C(=O)N[C@@H](CO)C(=O)N[C@@H](CCC(=O)N)C(=O)N[C@@H](Cc1ccc(cc1)O)C(=O)N[C@@H](CCC(=O)O)C(=O)N[C@@H

](Cc1ccccc1)C(=O)N[C@@H](CCCNC(=N)N)C(=O)N[C@@H](C(C)C)C(=O)N[C@@H](Cc1ccccc1)C(=O)N[C@@H](C)C(=O)……](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/rscapr2015bigdata-150423041734-conversion-gate02/85/Is-20TB-really-Big-Data-22-320.jpg)