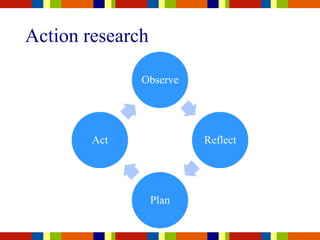

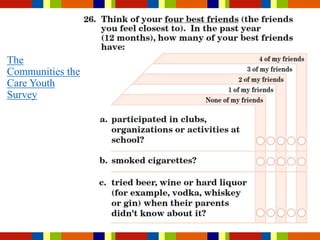

The document discusses the concept of evidence-informed practice in community engagement, highlighting the distinction between evidence-based practices and programs. It emphasizes the need for critical reflection, the cyclical process of defining practice questions, gathering and appraising evidence, and evaluating outcomes. It also covers accountability measures and the importance of adapting programs appropriately while maintaining fidelity to their original design.