Grainger's Global Supply Chain Re-Engineering Initiative

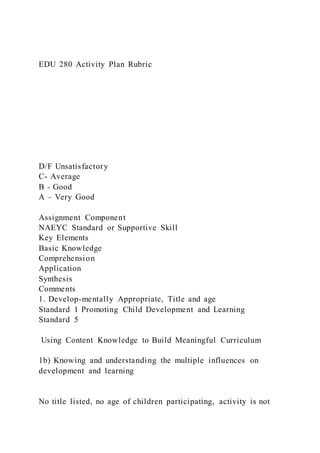

- 1. EDU 280 Activity Plan Rubric D/F Unsatisfactory C- Average B - Good A – Very Good Assignment Component NAEYC Standard or Supportive Skill Key Elements Basic Knowledge Comprehension Application Synthesis Comments 1. Develop-mentally Appropriate, Title and age Standard 1 Promoting Child Development and Learning Standard 5 Using Content Knowledge to Build Meaningful Curriculum 1b) Knowing and understanding the multiple influences on development and learning No title listed, no age of children participating, activity is not

- 2. age, culturally, or individually appropriate 0 - 7 points Title of the activity is listed, age of children participating is given, activity is not age, culturally, or individually appropriate 8 points Title of the activity is listed, age of children participating is given, activity more appropriate for a younger or older age group. Activity is individually and culturally appropriate 9 points Title of the activity is listed, age of children participating is given, activity is appropriate for the age of the individual children participating and is culturally appropriate 10 points 2. Area of Develop-ment Standard 1: Promoting Child Development and Learning 1c) Using developmental knowledge to create healthy, respectful, supportive, and challenging learning environments Area of development is not given 0 -11 points Area of development is listed, but is not related to the activity 12 points Area of development is listed, but is not a primary area of development for this activity 13 points

- 3. Area of Development is listed and is appropriate for the activity 14 points 3. Standard Addressed by the activity Standard 5: Skills in Identifying and Using Professional Resources 5a)Understanding content knowledge and resources in academic disciplines A subdomain, goal or developmental indicator from a source other than the standard course of study is listed or no standard is listed 0 -11 points A subdomain, goal or developmental indicator is listed, but it is from the incorrect standard course of study 12 points 2-3 subdomains, goals or developmental indicators from the appropriate standard course of study is listed, but it is not related to the activity 13 points At least 4 subdomains, goals or developmental indicators from the appropriate standard course of study is listed. The standard is related to the area of develop-ment and the activity 14 points 4. Materials Standard 4: Using Developmen-tally Effective Approaches to Connect with

- 4. Children/Family 4c) Using a broad repertoire of develop-mentally appropriate teaching/ learning approaches No materials are listed 0 -11 points Materials list includes materials that are not safe for use by children of this age 12 points Materials are listed, but the list is incomplete, all materials listed are safe for use by children of this age 13 points All materials needed to complete the activity are listed; all materials are safe for use by children of this age 14 points 5. Procedures Standard 5: Teaching and Learning 5c) Using their own knowledge, appropriate early learning standards, and other resources to design, implement, and evaluate meaningful, challenging curricula for each child Activity is designed for a large group, procedures for completing the activity are not included 0 - 11 points Activity is designed for small group of children, procedures for completing the activity are vague, the activity is teacher directed, no open-ended questions are

- 5. included 12 points Activity is designed for individual or small group of children, procedures for completing the activity are clear, the activity is child directed, no open-ended questions are included 13 points Activity is designed for individual or small group of children, procedures for completing the activity are clear, the activity is child directed, open-ended questions are included to encourage children’s thinking about the activity 20 points 6.Assess-ment of children’s progress Standard 3 Observing, Documenting and Assessing to Support young Children and Families 3a)Understanding the goals, benefits, and uses of assessment Method of documenting children’s progress is not given 0 - 11 points The method of documenting children’s progress is not developmentally appropriate 12 points Method of documenting children’s progress is listed and develop-mentally appropriate. The method for document-ing children’s progress does not measure the standard addressed in the activity 13 points

- 6. Method of document- ing children’s progress is listed and develop-mentally appropriate, an appropriate method for measuring the standard chosen 14 points 7. Family Involvement and Assessment Partnership Standard 3: Observing, documenting and Assessing to Support Young Children and Families 3b) Knowing about assessment partnerships with families and with professional colleagues No family involvement information included 0 - 11 points Meaningful family involvement information included, no suggestions for families to observe their children’s progress toward meeting this standard, no method for sharing family’s assessment with teacher 12 points Meaningful family involvement information included, fewer than 3 suggestions for families to observe their children’s progress toward meeting this standard, no method for sharing family’s assessment with teacher 13 points Meaningful family involvement information included, 3 suggestions for families to observe their children’s progress toward meeting this standard, method for sharing family’s assessment with the teacher 14 points Name __ _________________ Date:___ _____________ TOTAL POINTS ______________

- 7. Grainger: Re-Engineering an International Supply Chain case W90C84 December 8, 2010 Published by WDI Publishing, a division of the William Davidson Institute (WDI) at the University of Michigan. ©2010 Gary Scalzitti and Amitabh Sinha. Gary Scalzitti from Grainger and Amitabh Sinha, Assistant Professor at the University of Michigan’s Ross School of Business, developed this case. Acknowledgements go to Sung Hwan Cho, Lisa VanLanduyt and Aditya Vedantam, whose internal report from a Tauber Institute for Global Operations project contributed to the case. Historically, Grainger had been a US-centric business. However, between 2000 and 2010, its focus expanded significantly and Grainger was in the process of establishing a world-class global supply chain. In 2009, a strategic initiative was created to re-engineer the Grainger global supply chain. The initiative paired a team of three graduate students from the University of Michigan with an internal team of supply chain leaders and subject-matter experts focused on taking both time and cost out of the global supply chain and creating a more robust global infrastructure. The student team proposed two primary supply chain re-engineering options, and the company had to make a decision about which, if either, of those options to pursue.

- 8. Company Background Grainger, with 2008 sales of $6.9 billion, was a leading broad- line supplier of facilities maintenance products serving businesses and institutions in the United States, Canada, Mexico, China, Panama, and other countries. Through a highly integrated network including more than 600 branches, 18 distribution centers and multiple Web sites, Grainger’s employees helped their nearly 2 million customers, as the company’s motto touted, to “get it done.” Details of Grainger’s business profile are provided in Exhibit 1. When a customer needed one of the products that Grainger sold, the customer often needed it right away. A Grainger box carried more than just the products that came inside it, since Grainger differentiated itself from its competition in many ways. The company prided itself on outstanding customer service, easy ways for customers to do business, and high levels of inventory availability. Grainger offered almost 900,000 products, from safety supplies to pumps and motors to electrical supplies and fasteners—products that helped keep customers’ businesses running. Whether a valve broke on a water pipe, an electrical fuse blew, causing lights to go out in a hospital, or a drill bit broke off during a job, these issues had to be resolved quickly. Customers also depended on Grainger for everyday supplies such as air filters and cleaning supplies. Just offering customers a wide range of products, however, was not enough. Grainger provided 24/7 customer service, a network of local branches, a team of dedicated sellers who understood their customers’ businesses, easy online ordering, and same- and next-day delivery. This document is authorized for use only in Daniel Suarez's

- 9. GOMBA_OCt2019_O3 - Global Supply Chain Management at IE Business School from Feb 2021 to Jul 2021. 2 Grainger: Re-Engineering an International Supply Chain W90C84 Customers relied on Grainger to help them save time and money by consolidating their purchases of maintenance, repair, and operating supplies. In the late 2000s, Grainger was growing in terms of revenue, product offerings, and geographical reach. (Exhibit 2 provides financial details for the years 2006 through 2008.) At the corporate level, Grainger’s strategic growth objectives were as follows: 1. Grow market share by being the indispensable partner to those who keep workplaces safe, efficient, and functioning. Operationally, this placed the focus on: • Product breadth and high availability • Being easy to do business with • Leveraging regional and global scale for cost and service advantage 2. Enhance gross profit through expansion of private label products which are sourced globally. • Grainger sourced products from manufacturers around the

- 10. globe under various private labels. Grainger sourced products from 21 countries in 2008, and those products carried gross margins that were about 60 percent higher than the company average. As of the end of 2008, the company globally sourced 22,000 stock keeping units (SKUs), which represented about 8 percent of company sales. In 2008, the company continued to expand and grow all of its private label products to 24 percent of overall sales. Brands such as Dayton® motors met customers’ needs while improving Grainger’s margins. 3. Grow international share through expansion across Latin America and Asia. Grainger US and Grainger Global Sourcing Supply Grainger United States (GUS) operated through a highly integrated network of over 400 branches, 14 distribution centers, and multiple Web sites in order to serve customers in the United States. In 2008, Grainger’s US business served some 1.7 million customers, who primarily represented industrial, commercial, and government maintenance departments. The MRO (maintenance, repair, and operations) market size in the US was estimated to be $125 billion, of which Grainger’s market share in 2008 was approximately 5 percent. (For the purpose of this case, only nine of the GUS distribution centers are to be considered.) Additionally, Grainger operated internationally. In North America, Acklands-Grainger (AGI) was Canada’s largest broad-line supplier of industrial, safety, and fastener products. The company served approximately 43,000 customers across Canada through 154 branches and five

- 11. distribution centers. The MRO market size in Canada was estimated to be $13 billion, of which Grainger’s market share in 2008 was approximately 6 percent. Grainger also operated in Mexico, as Grainger, S.A. de C.V. In 2008, the company served approximately 35,000 customers through 22 branches, a distribution center, a Spanish-language catalog, and grainger.com. mx. The MRO market size in Mexico was estimated to be $12 billion, of which Grainger’s market share in 2008 was approximately 1 percent. International expansion in other parts of the world was of sustained interest at Grainger, with much of the revenue growth over the next decade expected to come from outside North America. Many products sold by Grainger were nationally branded products (e.g. General Electric, 3M, Bosch), which were purchased from the respective vendors and made available to end customers via Grainger’s distribution network. Increasingly, Grainger had also been selling its private label products, because these offered an opportunity for increased profit margins and they met customers’ growing needs for low cost, high quality products. This document is authorized for use only in Daniel Suarez's GOMBA_OCt2019_O3 - Global Supply Chain Management at IE Business School from Feb 2021 to Jul 2021. 3 Grainger: Re-Engineering an International Supply Chain W90C84 Until 1997, both nationally branded and private label products

- 12. in the GUS catalog were sourced exclusively domestically. In 1997, the Grainger Global Sourcing (GGS) business unit was formed to develop an international, lower-cost supplier base for private-label items offered through the GUS catalog. Although GGS was a division of Grainger, its sole purpose was to act as a supplier to GUS. GGS was the largest supplier to GUS, and GGS-sourced private label products made up approximately half of GUS’s total private label sales. GGS offered 22,000 private label SKUs (products) in 10 of the 17 GUS catalog categories. GGS sourced products from over 300 suppliers in 21 countries including China, Taiwan, Mexico, Indonesia, India, and South Korea. Seventy-one percent of these suppliers were in China. All products sourced by GGS were shipped to and processed in a single distribution center (DC) in Kansas City, Missouri. GUS placed orders with GGS for its products. GGS shipped products to the nine GUS DCs daily based on these orders. Thus, the GGS network in the US consisted of a single distribution center in Kansas City supplying the nine GUS distribution centers as its customers. Although Grainger sourced from manufacturers around the world, China and Taiwan comprised approximately 80% of all globally sourced products. Current State of the Grainger Global Sourcing Supply Chain This section describes the status of GGS and identifies the key levers with respect to this product flow. GGS China/Taiwan to US Supply Chain Product Flow

- 13. Figure 1 outlines the flow of products from China and Taiwan to the GGS DC and out to the nine domestic customers and some international customers. GGS had over 300 suppliers in China and Taiwan (71% of its entire supplier base and 80% of the volume). Because Grainger’s specifications for its products were unique, there was, in many cases, only one supplier for a product line, and GGS had to work with that supplier to develop new manufacturing programs specifically for GGS. For example, GGS could have found a supplier that produced a limited line of quality work gloves but did not produce the breadth or variety that Grainger required. GGS would work with the supplier to create specifications and manufacturing recommendations for the complete line. The unique specifications and variety in the product line often resulted in high minimum order quantities (MOQs) because the supplier incurred setup costs to switch the manufacturing lines to GGS products. High MOQs, in turn, sometimes led to excess GGS inventory of slow-moving items, which were stocked for completeness rather than for true demand. This document is authorized for use only in Daniel Suarez's GOMBA_OCt2019_O3 - Global Supply Chain Management at IE Business School from Feb 2021 to Jul 2021. 4 Grainger: Re-Engineering an International Supply Chain W90C84

- 14. Figure 1 Product Flow: China/Taiwan to US All contracts with GGS suppliers were Free on Board (FOB) port. The supplier owned the products until they were placed on an ocean vessel and was responsible for all costs incurred to transport finished products to the port. International logistics were coordinated for GGS by a third-party freight forwarder, which managed container transport and ship bookings for all suppliers’ cargo. Suppliers whose cargo filled an ocean freight container received a container from the freight forwarder, filled it, and sealed it at the factory (these were factory-direct containers). All cargo was floor-loaded (packed directly on the floor without the use of pallets). The freight forwarder transported the sealed containers to the proper shipping vessel, and they were not opened again until they reached Kansas City. Factory-direct containers represented 89% of all containers shipped to GGS from China and Taiwan. Suppliers whose cargo did not fill an ocean freight container delivered their cargo to one of the freight forwarder’s five consolidation centers. The freight forwarder built containers by combining one supplier’s products with products from other small GGS suppliers. GGS products were never combined with non-GGS cargo. These consolidated containers represented 11% of all containers that were shipped to GGS from China and Taiwan. GGS cargo was transported in four container sizes, measured by their length in feet: 20’, 40’, 40’ high cube, and 45’. The relative proportion of each container size used by GGS in 2008 is listed in Table 1 below. It should be noted that all numbers in the case and in the exhibits are artificial and illustrative, and should

- 15. not be considered primary data. Table 1 GGS Container Mix in 2008 Container Size Proportion of Factory- Direct Containers Proportion of Consolidated Containers 20’ 21% 27% 40’ 50% 60% 40’ High Cube 28% 11% 45’ 3% 3% This document is authorized for use only in Daniel Suarez's GOMBA_OCt2019_O3 - Global Supply Chain Management at IE Business School from Feb 2021 to Jul 2021. 5 Grainger: Re-Engineering an International Supply Chain W90C84 It was most cost-effective to use 40’ or 40’ high cube containers rather than 20’ containers because they had a significantly lower cost per cubic meter (cbm) of cargo. The cost of a 20’ container was 80% of the cost of a 40’ container, resulting in a 165% cost per cubic meter premium for a 20’ container over a 40’ container.

- 16. GGS’s consolidated containers skewed toward the smaller sizes, primarily due to the limited volume of cargo that was consolidated (only 11%) and the dispersion of consolidation centers. The freight forwarder operated five consolidation centers in China, and cargo was sent to the nearest one. GGS placed a minimum container utilization requirement and a dwell time limit on all containers. Containers had to be at least 83% full by either weight or volume, and cargo could not wait more than seven days in the consolidation center for additional cargo to arrive. As a result, on average, all containers were utilized to 85%, and consolidated cargo was shipped in smaller containers than was factory-direct cargo. Both factory-direct and consolidated containers from China and Taiwan flowed primarily through five major ports (Shanghai, Ningbo, Yantian, Qingdao, and Kaohsiung). This flow represented approximately 80% of all GGS purchases in 2008. The distribution of this volume is shown in Table 2. Table 2 Proportion of GGS Shipments Passing Through Ports in China and Taiwan in 2008 Port Center Volume Percentage Shanghai/Ningbo (China) 36% Yantian/Hong Kong (China) 33% Kaohsiung (Taiwan) 9% Qingdao (China) 5%

- 17. All containers entered the US at either the Seattle, Washington, port (40% of containers) or the Los Angeles, California, port (60% of containers). For the future, it was proposed that all containers would enter exclusively through ports in California. From there, the containers were transported to Kansas City by rail, and then transferred to the Kansas City DC by truck. In Kansas City, GGS utilized an offsite storage facility because it had reached capacity in the DC building itself. At the DC, the containers were unloaded. Representative items from every SKU in the container were processed through a quality assurance check before the products were stocked in the storage racks. Any SKU whose items did not pass the quality check were quarantined. These products were reworked (corrected) by the GGS warehouse staff when possible or sent back to the supplier for correction. In 2008, 3% of all SKU’s inspected required rework. When GUS placed an order with GGS, the order was processed and picking/packing instructions were generated. Some products required additional assembly. To improve the efficiency of ocean transport, products that would be too bulky if shipped fully assembled (such as hand carts with wheels) were shipped in a partially assembled state. When these products were ordered by GUS, GGS performed final assembly before shipping the products to GUS. All items in the order were then packed on pallets and loaded onto 53’ trucks. In 2008, 73% of shipments were to GUS DCs that were either south or east of Kansas City. Nineteen percent went to the GUS Kansas City DC, where products were simply shifted from the GGS side to the GUS side of the warehouse. The remaining eight percent was sent to the west coast. By 2012, the west coast volume was expected to be 18%. That meant that fully 18% of GGS

- 18. outbound shipments would be transported into Kansas City and back to the west coast. A very small percentage of GGS products was purchased by the Canada, Mexico, and China Grainger divisions. The quantities were often limited due to the relative sizes of the MOQs compared to the existing demand for these products within these other business units. However, when there was need for these GGS This document is authorized for use only in Daniel Suarez's GOMBA_OCt2019_O3 - Global Supply Chain Management at IE Business School from Feb 2021 to Jul 2021. 6 Grainger: Re-Engineering an International Supply Chain W90C84 products in the other business units, the products first came to Kansas City, as described above, and were re-exported to the Canada, Mexico, and China divisions from there. Further, Grainger also had newer divisions and joint ventures in India, South Korea, and Japan, which had no access to the GGS products at all. Lead Time In aggregate, the GGS products flowed from the time the order was placed with the GGS supplier to the time the product was stocked in the Kansas City DC. GGS order-to-stock lead time was approximately three months. Exhibit 3 and Figures 2 and 3 are schematic drawings of this aggregate lead time broken

- 19. down by phase. (Note that there is a difference in lead time between products that are consolidated and products that are shipped factory-direct. This difference is due to the potential for additional dwell time at the consolidation center.) Figure 2 Lead Time Breakdown in China and Taiwan Order Manufacture Consol Ocean LT (consol) 4 d 57 d 7 d 14 d LT (direct) 4 d 57 d 0 d 14 d Figure 3 GGS Operating Expense and Lead Time Breakdown in the US Rail Transfer Stock PO to Ship Ship to GUS Lead Time 7 d 2 d 2 d 3 d 3 d This document is authorized for use only in Daniel Suarez's GOMBA_OCt2019_O3 - Global Supply Chain Management at IE Business School from Feb 2021 to Jul 2021. 7 Grainger: Re-Engineering an International Supply Chain W90C84 Operating Expense and Overall Metrics For this discussion, the supply chain operating expense is made

- 20. up of all expenses to transport products from China and Taiwan to the GGS DC, process them, and transport them to the nine GUS DCs. GGS measured the efficiency of its supply chain by viewing the operating expense as a percent of the cost of goods sold (COGS), as well as by overall inventory position and service level. These metrics for the GGS supply chain in 2008 are listed in Table 3. Table 3 GGS Supply Chain Overall Metrics in 2008 Category Current State Operating Expense Expense $28.3 M Operating Expense as % of COGS 14.3% Lead Time GGS Order to Stock 90 days GUS In-Transit 1-6 days GUS In-Transit Distance (avg.) 776 miles Service Level Mature Items 96% New Items 84% Other

- 21. Container Utilization 85% Average Inventory Position $85 M Summary With respect to Grainger’s global distribution and operational efficiency goals, the company experienced the following issues: • Most suppliers were following their own procedures, or “doing their own thing.” They were loading containers with only their products and sending them directly to Kansas City. GGS did not have control of the products until they reached its DC in the US. • All GUS DCs were served from a single GGS DC in Kansas City. The distance traveled to many of these DCs was long, and products going to the west coast actually traveled over the same route twice (on the inbound trip to Kansas City and again on the outbound trip to the west coast GUS DC). • GGS’s ability to sell its products to Grainger’s international divisions in a cost-effective or lead- time-efficient manner was limited due to transfer pricing, incremental processing costs, and time associated with bringing the products all the way into the US, then exporting them back out to those divisions. Network Optimization As Grainger looked toward its future and considered the company’s strategic growth objectives, it

- 22. became clear that a major redesign of the GGS supply chain was needed. Furthermore, this redesign would create a rare opportunity to fix some of the inefficiencies that existed in the supply chain’s current state. This document is authorized for use only in Daniel Suarez's GOMBA_OCt2019_O3 - Global Supply Chain Management at IE Business School from Feb 2021 to Jul 2021. 8 Grainger: Re-Engineering an International Supply Chain W90C84 When the team of students arrived at Grainger in May 2009, they quickly realized that a project of this scope and magnitude offered many levers that could be worked to meet Grainger’s strategic growth objectives as well as eliminate inefficiencies. After significant brainstorming with the executive team and domain specialists within Grainger, the team converged on three alternatives that appeared to be most promising. The three alternatives are described below. 1. Increased consolidation in China: As mentioned earlier, most of the containers coming from China were “factory-direct” in that the suppliers manufactured and shipped the containers straight from their facilities to Kansas City. Given that there were over 300 such suppliers, some sending just a handful of containers per year, Grainger suspected that there was an opportunity for significant savings by consolidation in China.

- 23. Specifically, it was proposed that Grainger operate consolidation centers in China at the same port locations used in the existing network: Shanghai-Ningbo, Yantian, Kaohsiung, and Qingdao. Suppliers would then send their products only to their assi gned consolidation centers. Grainger (or a third party operating on behalf of Grainger) would take ownership of the products at the consolidation centers and consolidate the products from different suppliers as well as for different destinations. These consolidated containers would then be shipped overseas under Grainger’s existing shipping arrangements. This re-engineering offered significant opportunities for cost reduction. Transportation costs could decrease in two ways. First, there would be more efficient use of container space. Second, consolidation would allow for a reduction in the number of 20’ containers used, which were highly cost-inefficient. Because each manufacturer would not need to wait to fill a full container by itself, the average order size would also decrease, which would reduce inventory costs. Also, non-US Grainger businesses, which typically have lower volumes, could now be served directly from the consolidation centers in quantities consistent with their sales volumes. However, opening consolidation centers in China carried significant risks, and it would represent a major new presence in China by Grainger. Although the consolidation decision had many components, it was felt that a pilot study would demonstrably generate enough savings to justify consolidation. As a pilot study, the team was advised to

- 24. consider opening a consolidation center at Yantian. At the time, Yantian shipped out approximately 62,700 cbm of material annually, using a mix of 40’ and 20’ containers as described in Exhibit 4. A reasonable target would be to assume that 85% of the material would be consolidated, and a container utilization level of 96% would be achievable on consolidation. Of course, consolidation would enable reducing the use of the inefficient 20’ containers; for the pilot study, it was believed that if 85% of the material were consolidated, then the remaining 15% of unconsolidated material would all be from high-volume suppliers who would use only 40’ containers. All other rel evant data are provided in Exhibit 5. Can the consolidation investment in Yantian be justified? 2. More primary DCs in the US: A large quantity of GGS products came from Asia, with the majority entering the US via the port of Los Angeles. Grainger already had a GUS DC at LA, but this DC received products from Kansas City and distributed them to the stores in its operating area. Would it be possible to set up a new primary import DC operated by GGS in addition to a GUS DC serving the southwestern US? In this scenario, some of the containers coming from Asia would be offloaded at the port of entry and directed to the new primary import DC for distribution in the western United States, while the remainder would be routed to Kansas City. This document is authorized for use only in Daniel Suarez's GOMBA_OCt2019_O3 - Global Supply Chain Management at IE Business School from Feb 2021 to Jul 2021.

- 25. 9 Grainger: Re-Engineering an International Supply Chain W90C84 A similar change could be made in the East Coast, by converting the DC at Greenville, SC, into an import warehouse operated by GGS as well. Containers would arrive from Asia to Greenville and would then be dispatched from Greenville to the four GUS DCs serving the East Coast: Greenville, Jacksonville, New Jersey and Cleveland. Any goods not destined for these four DCs would be sent to Kansas City for further distribution and processing. Although creating these two primary DCs offered substantial savings in transportation costs, there were several other activities that would need to be examined carefully so that there would be no net increase in costs. The Kansas City DC, being the only primary DC for the entire country, allowed for maximum pooling of demand uncertainty, thus allowing for very low levels of safety stock to be maintained. If more primary DCs were opened in the US, would the safety stocks that needed to be maintained at each of the primary DCs result in an overall increase in inventory costs? Were there other ways to mitigate this possible inventory cost increase? Additionally, the Kansas City DC performed other activities on the goods once they were unpacked from the containers. These included quality assurance, assembly, and kitting. Opening

- 26. more primary DCs would mean these activities would have to be replicated at the other primary DCs, potentially increasing labor and equipment costs. As a pilot study, the team was advised to consider whether opening a new GGS DC in the West Coast (WCDC) could be justified. If a GGS DC were opened in the West Coast, would Los Angeles be the only GUS DC served by it? The Dallas GUS DC was also close enough that it could make sense to supply it from the WCDC as well. Exhibit 5 displays the demand information at each of the nine GUS DCs, their distances from KC, and a tentative site for the WCDC, while Exhibit 6 provides a cost breakdown of items that would impact the WCDC opening decision. For this calculation, assume that pipeline inventory costs are ignored, but cycle and safety inventory costs are incurred at the primary DCs. When freight and inventory costs are considered, does it make sense to set up and operate the WCDC? 3. Retain existing supply chain: The third alternative was to avoid the major re-engineering activities, because of their risks, and to incrementally improve the processes within the existing supply chain so as to achieve Grainger’s objectives. For instance, the relationship with Grainger’s suppliers in China could be managed so that they were encouraged to consolidate products on their own, reducing shipping costs. Given the significant risks of the two major redesign initiatives, there was significant push- back within Grainger against the major changes. An executive in GGS stated that the current

- 27. supply chain was, in fact, optimal when all the costs and risks were considered, and the redesign initiatives were being considered only out of a “myopic focus on transportation costs.” With the economy going into recession in 2009, fuel and transportation costs were already dropping dramatically, removing some of the impetus for a major redesign. As the student team concluded its presentation to the executive steering committee, it came away with conflicting opinions on what to recommend. For each of the three alternatives presented, there were some executives who thought that the idea was great, while others downplayed the benefits and emphasized the risks. The students realized that the only way to get everyone on board (and convince themselves) on an appropriate redesign would be to conduct a thorough quantitative analysis of the scenarios. In the words of the steering committee at Grainger, “Show us the numbers!” This document is authorized for use only in Daniel Suarez's GOMBA_OCt2019_O3 - Global Supply Chain Management at IE Business School from Feb 2021 to Jul 2021. 10 Grainger: Re-Engineering an International Supply Chain W90C84 Exhibits

- 28. Exhibit 1 Key Facts about Grainger 2008 sales $6.9 billion ($1.5 billion via e-commerce) Employees 18,000 Branches 617 Distribution centers 18 Customers 1.8 million in 153 countries Products offered: 900,000 Suppliers 3,000 Large, diverse customer base Broad and deep product portfolio Power Tools, 4% Power Transmission, 3% Material Handling, 16% Safety & Security, 14% Pumps/Plumbing, 9% Cleaning & Maintenance, 9% Lighting, 7% Ventilation, 6% Electrical, 7%

- 29. Hand Tools, 7% Fluid Power, 5% HACR, 4% Metal Working, 5% Motors, 3% Government, 19% Other, 4% Commercial, 19% Resellers, 6% Agriculture & Mining, 2% Heavy Mfg, 19% Light Mfg, 10% Retail, 7% Contractors, 14% This document is authorized for use only in Daniel Suarez's GOMBA_OCt2019_O3 - Global Supply Chain Management at IE Business School from Feb 2021 to Jul 2021. 11

- 30. Grainger: Re-Engineering an International Supply Chain W90C84 This document is authorized for use only in Daniel Suarez's GOMBA_OCt2019_O3 - Global Supply Chain Management at IE Business School from Feb 2021 to Jul 2021. 12 Grainger: Re-Engineering an International Supply Chain W90C84 Exhibit 2 Grainger 2006-2008 Financial Summary This document is authorized for use only in Daniel Suarez's GOMBA_OCt2019_O3 - Global Supply Chain Management at IE Business School from Feb 2021 to Jul 2021. 13 Grainger: Re-Engineering an International Supply Chain W90C84 Exhibit 3 GGS Supply Chain Activity Detail Stage Description GGS Order Processing GGS reviews inventory monthly, and places orders with its

- 31. manufacturers. Manufacture Suppliers typically take approximately 57 days to manufacture. Consolidate Some suppliers send the product to consolidation centers, where they are consolidated to fill containers. Most suppliers fill up the containers themselves at their facilities, and deliver the packed containers to the port specified by GGS. Ocean Shipment GGS’s contract with the steamship lines are from the China/ Taiwan port to the door at the Kansas City DC. The rate to ship a container includes each of these shipment legs. Dray – Port to Rail Rail to Kansas City Dray – KC Rail to KC DC Warehousing Unload containers. QA-check all SKUs. Rework SKUs that fail QA. Stock keep. The approximate time from order placement to stocking is about 3 months. GUS Order Processing

- 32. Create order picking/packing instructions. Pick items. Assemble items (when required). Pack items on pallets. Load pallets into truck. GUS Order Shipment Shipment from GGS to GUS DCs. This expense is paid for by GUS. This document is authorized for use only in Daniel Suarez's GOMBA_OCt2019_O3 - Global Supply Chain Management at IE Business School from Feb 2021 to Jul 2021. 14 Grainger: Re-Engineering an International Supply Chain W90C84 Exhibit 4 GGS Operating Expenses Detail – Yantian Consolidation (forecast data for 2012) Data for consolidation decision Item Units Value Annual volume cubic meters 190000 Yantian volume percent 33% Targeted consolidation percent 85% Container utilization after consolidation percent 96%

- 33. Annual fixed cost of running consol $/year $75,000 One-time fixed cost of opening consol $ $250,000 Unit holding cost at Yantian consol $/cubic meters per year $5 Unit consolidation material handling cost $/cubic meters $1.40 Container size 40’ 20’ Container capacity cubic meters 67 34 Current container volume out of Yantian containers/year 918 612 Freight, Yantian to US port $/container $600 $480 Exhibit 5 GUS Distribution Centers (Forecast data for 2012) Annual Demand (Cubic Meters) Warehouse Mean Standard deviation Miles from Kansas City Miles from West Coast Kansas City 20900 6270 0 1570 Cleveland 17100 5130 800 2290

- 34. New Jersey 24700 7410 1200 2725 Jacksonville 15200 4560 1150 2375 Chicago 22800 6840 520 1980 Greenville 15200 4560 940 2270 Memphis 17100 5130 510 1745 Dallas 22800 6840 500 1390 Los Angeles 34200 10260 1620 50 Total 190000 This document is authorized for use only in Daniel Suarez's GOMBA_OCt2019_O3 - Global Supply Chain Management at IE Business School from Feb 2021 to Jul 2021. 15 Grainger: Re-Engineering an International Supply Chain W90C84 Exhibit 6 GGS Operating Expenses Detail – US (Forecast data for 2012) Data for US Distribution Centers Decision Item Units Value

- 35. US rail freight per cbm per mile $0.0018 US truck freight per cbm per mile $0.0220 GGS inventory review period months 1 GGS lead time months 3 US holding cost $/cbm per year $7.50 Targeted service level % 98% One-time fixed cost of WCDC $ $2,300,000 Annual operating cost of WCDC $ $350,000 Variable cost at WCDC per cbm annual throughput $5.00 Variable cost at KC facility per cbm annual throughput $3.00 This document is authorized for use only in Daniel Suarez's GOMBA_OCt2019_O3 - Global Supply Chain Management at IE Business School from Feb 2021 to Jul 2021. Established at the University of Michigan in 1992, the William Davidson Institute (WDI) is an independent, non-profit research and educational organization focused on providing private-sector solutions in emerging markets. Through a unique structure that integrates research, field-based collaborations,

- 36. education/training, publishing, and University of Michigan student opportunities, WDI creates long-term value for academic institutions, partner organizations, and donor agencies active in emerging markets. WDI also provides a forum for academics, policy makers, business leaders, and development experts to enhance their understanding of these economies. WDI is one of the few institutions of higher learning in the United States that is fully dedicated to understanding, testing, and implementing actionable, private- sector business models addressing the challenges and opportunities in emerging markets. This document is authorized for use only in Daniel Suarez's GOMBA_OCt2019_O3 - Global Supply Chain Management at IE Business School from Feb 2021 to Jul 2021. North Carolina Foundations for Early Learning and Development North Carolina Foundations Task Force

- 37. North Carolina Foundations for Early Learning and Development North Carolina Foundations Task Force ii North Carolina Foundations for Early Learning and Development North Carolina Foundations for Early Learning and Development © 2013. North Carolina Foundations Task Force. Writers Catherine Scott-Little Human Development and Family Studies Department UNC-Greensboro Glyn Brown SERVE Center UNC-Greensboro Edna Collins Division of Child Development and Early Education NC Department of Health and Human Services

- 38. Editors Lindsey Alexander Lindsey Alexander Editorial Katie Hume Frank Porter Graham Child Development Institute UNC-Chapel Hill Designer Gina Harrison Frank Porter Graham Child Development Institute UNC-Chapel Hill Photography Pages: 60 and 143 courtesy of UNC-Greensboro, Child Care Education Program. 36, 54, 135, 136, front cover (group shot), and back cover (infant) courtesy of NC Department of Health and Human Services, Division of Child Development and Early Education. All others: Don Trull, John Cotter Frank Porter Graham Child Development Institute UNC-Chapel Hill The North Carolina Foundations for Early Learning and Development may be freely reproduced without permission for non-profit, educational purposes.

- 39. Electronic versions of this report are available from the following websites: http://ncchildcare.dhhs.state.nc.us http://www.ncpublicschools.org/earlylearning Suggested citation: North Carolina Foundations Task Force. (2013). North Carolina foundations for early learning and development. Raleigh: Author. Funding for this document was provided by the North Carolina Early Childhood Advisory Council using funds received from a federal State Advisory Council grant from the Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. http://www.ncpublicschools.ort/earlylearning http://www.ncpublicschools.ort/earlylearning iii North Carolina Foundations for Early Learning and Development Table of Contents Acknowledgements . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . v Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1 Purpose of Foundations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2

- 40. Organization of This Document . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3 How to Use Foundations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6 Domains, Subdomains, and Goals Overview . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8 Guiding Principles . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13 Effective Use of Foundations with All Children . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15 Foundations and Children’s Success in School . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17 Helping Children Make Progress on Foundations Goals: It Takes Everyone Working Together . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .20 Frequently Asked Questions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 22 Approaches to Play and Learning (APL) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 26 Curiosity, Information-Seeking, and Eagerness . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .30 Play and Imagination . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 34 Risk-Taking, Problem-Solving, and Flexibility . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

- 41. . . . . . . . . . 38 Attentiveness, Effort, and Persistence . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 42 Emotional and Social Development (ESD) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 48 Developing a Sense of Self . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 52 Developing a Sense of Self With Others . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 56 Learning About Feelings . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 61 iv North Carolina Foundations for Early Learning and Development Health and Physical Development (HPD) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 66 Physical Health and Growth . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .70 Motor Development . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 75 Self-Care . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .80 Safety Awareness . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

- 42. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .84 Language Development and Communication (LDC) . . . . . . 88 Learning to Communicate . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 93 Foundations for Reading . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .104 Foundations for Writing . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 111 Cognitive Development (CD) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 116 Construction of Knowledge: Thinking and Reasoning . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 121 Creative Expression . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 127 Social Connections . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 131 Mathematical Thinking and Expression . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 137 Scientific Exploration and Knowledge . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .144 Supporting Dual Language Learners (DLL) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 149 Defining Dual Language Learners . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

- 43. . . . . . . . . . . 149 The Dual Language Learning Process . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 149 DLL and Culture . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .150 The Importance of Families . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 152 DLL and Standards . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 153 Conclusion . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 154 Glossary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 155 Selected Sources . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 163 v North Carolina Foundations for Early Learning and Development Acknowledgments I n 2011, the North Carolina Early Childhood Advisory Council (ECAC) launched and funded the important project of revising the Infant-Toddler Foundations and

- 44. Preschool Foundations to create the North Carolina Foundations for Early Learning and Development—a single document that describes children’s development and learning from birth to age five. Leaders from the Division of Child Development and Early Education as well as the Office of Early Learning in the Department of Public Instruction provided critical advice, oversight, and vision on the Foundations and its implementation. As listed below, many individuals from across the state devoted their time and expertise to this task force. We are grateful to everyone’s work on this important resource for our state. This publication is dedicated to North Carolina’s early childhood professionals, teachers, and caregivers who nurture and support the development of many young children while their families work or are in school. Expert Reviewers Laura Berk Professor Emeritus, Psychology Department Illinois State University Sharon Glover Cultural Competence Consultant Glover and Associates Melissa Johnson Pediatric Psychologist WakeMed Health and Hospitals

- 45. Patsy Pierce Speech Language Pathologist Legislative Analyst NC General Assembly Research Division NC Foundations Task Force Inter-Agency Leadership Team Division of Child Development and Early Education NC Department of Health and Human Services Deb Cassidy Anna Carter Edna Collins Jani Kozlowski Lorie Pugh Office of Early Learning NC Department of Public Instruction John Pruette Jody Koon Human Development and Family Studies Department UNC-Greensboro Catherine Scott-Little, Co-Facilitator Sheresa Boone Blanchard Frank Porter Graham Child Development Institute UNC-Chapel Hill Kelly Maxwell, Co-Facilitator

- 46. vi North Carolina Foundations for Early Learning and Development NC Foundations Task Force (cont .) Foundations Revisions Expert Workgroup Norm Allard Pre-K Exceptional Children Consultant Office of Early Learning NC Department of Public Instruction Joe Appleton Kindergarten Teacher Sandy Ridge Elementary School Cindy Bagwell Co-Chair of Cognitive Development Workgroup Early Childhood Education Consultant Office of Early Learning NC Department of Public Instruction Harriette Bailey Assistant Professor Birth-Kindergarten Program Coordinator Department of Education, Shaw University Sheila Bazemore Education Consultant Division of Child Development and Early Education NC Department of Health and Human Services Bonnie Beam Director

- 47. Office of School Readiness, Cleveland County Schools Gwen Brown Regulatory Supervisor Division of Child Development and Early Education NC Department of Health and Human Services Paula Cancro Preschool Director Our Lady of Mercy Catholic School Deborah Carroll Branch Head Early Intervention, Division of Public Health NC Department of Health and Human Services Kathryn Clark Professor, Child Development Program Coordinator Child Development, Meredith College Renee Cockrell Pediatrician Rocky Mount Children’s Developmental Services Agency Lanier DeGrella Infant Toddler Enhancement Project Manager Child Care Services Association Sherry Franklin Quality Improvement Unit Manager Division of Public Health NC Department of Health and Human Services Kate Gallagher Child Care Program Director Frank Porter Graham Child Development Institute

- 48. UNC-Chapel Hill Khari Garvin Director, Head Start State Collaboration Office Office of Early Learning NC Department of Public Instruction Cristina Gillanders Scientist Frank Porter Graham Child Development Institute UNC-Chapel Hill Pamela Hauser Child Care Licensing Consultant Division of Child Development and Early Education NC Department of Health and Human Services Ronda Hawkins Chair of Emotional and Social Development Workgroup Early Childhood Program Coordinator Sandhills Community College Patricia Hearron Chair of Approaches to Learning Workgroup Professor, Family and Consumer Sciences Appalachian State University Staci Herman-Drauss Infant Toddler Education Specialist Child Care Services Association Vivian James 619 Coordinator Pre-K Exceptional Children, Office of Early Learning North Carolina Department of Public Instruction

- 49. LaTonya Kennedy Teacher Mountain Area Child and Family Center Doré LaForett Investigator Frank Porter Graham Child Development Institute UNC-Chapel Hill Beth Leiro Physical Therapist Beth Leiro Pediatric Physical Therapy Gerri Mattson Pediatric Medical Consultant Division of Public Health NC Department of Health and Human Services Janet McGinnis Education Consultant Division of Child Development and Early Education NC Department of Health and Human Services vii North Carolina Foundations for Early Learning and Development NC Foundations Task Force (cont .) Margaret Mobley Manager, Promoting Healthy Social Behavior in Child Care Settings Child Care Resources, Inc.

- 50. Judy Neimeyer Professor Emerita Specialized Education Services UNC-Greensboro Eva Phillips Instructor, Birth-Kindergarten Education Winston-Salem State University Jackie Quirk Chair of Health and Physical Development Workgroup Project Coordinator NC Child Care Health and Safety Resource Center UNC Gillings School of Global Public Health Amy Scrinzi Co-Chair of Cognitive Development Workgroup Early Mathematics Consultant Curriculum and Instruction Division NC Department of Public Instruction Janet Singerman President Child Care Resources, Inc. Diane Strangis Assistant Professor Child Development, Meredith College Dan Tetreault Chair of Language and Communication Workgroup K–2 English Language Arts Consultant Curriculum and Instruction Division NC Department of Public Instruction Brenda Williamson

- 51. Assistant Professor, Birth-Kindergarten Teacher Education Program Coordinator NC Central University Gale Wilson Regional Specialist NC Partnership for Children Catherine Woodall Education Consultant Division of Child Development and Early Education NC Department of Health and Human Services Doyle Woodall Preschool Teacher Johnston County Schools Dual Language Learners Advisory Team Catherine Scott-Little, Chair Associate Professor, Human Development and Family Studies UNC-Greensboro Tanya Dennis Telamon Corporation Shari Funkhouser Pre-K Lead Teacher Asheboro City Schools Cristina Gillanders Scientist Frank Porter Graham Child Development Institute UNC-Chapel Hill

- 52. Belinda J. Hardin Associate Professor, Specialized Education Services UNC-Greensboro Norma A. Hinderliter Special Education Expert Adriana Martinez Director Spanish for Fun Academy Tasha Owens-Green Child Care and Development Fund Coordinator Division of Child Development and Early Education NC Department of Health and Human Services Gexenia E. Pardilla Latino Outreach Specialist Child Care Resources Inc. Jeanne Wakefield Executive Director The University Child Care Center Strategies Workgroup Sheresa Boone Blanchard, Chair Child Development and Family Studies UNC-Greensboro Patsy Brown Exceptional Children Preschool Coordinator Yadkin County Schools Kristine Earl Assistant Director

- 53. Exceptional Children’s Department Iredell-Statesville Schools Cristina Gillanders Scientist Frank Porter Graham Child Development Institute UNC-Chapel Hill Wendy H-G Gray Exceptional Children Preschool Coordinator Pitt County School System viii North Carolina Foundations for Early Learning and Development NC Foundations Task Force (cont .) Patricia Hearron Professor, Family and Consumer Sciences Appalachian State University Staci Herman-Drauss Infant Toddler Education Specialist Child Care Services Association Tami Holtzmann Preschool Coordinator Thomasville City Schools Renee Johnson Preschool Coordinator Edgecombe County Public School

- 54. Jenny Kurzer Exceptional Children Preschool Coordinator Burke County Public Schools Brenda Little Preschool Coordinator Stokes County Schools Karen J. Long Infant Toddler Specialist Child Care Resources, Inc Jackie Quirk Project Coordinator NC Child Care Health and Safety Resource Center UNC Gillings School of Global Public Health Brenda Sigmon Preschool Coordinator Catawba County/Newton Conover Preschool Program Teresa Smith Preschool Coordinator Beaufort County Schools Susan Travers Exceptional Children Curriculum Manager and Preschool Coordinator Buncombe County Schools Rhonda Wiggins Exceptional Children Preschool Coordinator Wayne County Public Schools

- 55. 1 North Carolina Foundations for Early Learning and Development Introduction North Carolina’s young children. This document, North Carolina Foundations for Early Learning and Development (referred to as Foundations), serves as a shared vision for what we want for our state’s children and answers the question “What should we be helping children learn before kindergarten?” By providing a common set of Goals and Developmental Indicators for children from birth through kindergarten entry, our hope is that parents, educators, administrators, and policy makers can together do the best job possible to provide experiences that help children be well prepared for success in school and life. This Introduction provides important information that adults need in order to use Foundations effectively. We discuss the purpose of the document, how it should be used, and what’s included. We’ve also tried to answer questions that you might have, all in an effort to help readers understand and use Foundations as a guide for what we want children to learn during their earliest years. Foundations can be used to: • Improve teachers’ knowledge of child development;

- 56. • Guide teachers’ plans for implementing curricula; • Establish goals for children’s development and learning that are shared across programs and services; and • Inform parents and other family members on age-appropriate expectations for children’s development and learning. C hildren’s experiences before they enter school matter—research shows that children who experience high-quality care and education, and who enter school well prepared, are more successful in school and later in their lives. Recognizing the importance of the early childhood period, North Carolina has been a national leader in the effort to provide high-quality care and education for young children. Programs and services such as Smart Start, NC Pre-K, early literacy initiatives, Nurse Family Partnerships and other home visiting programs, and numerous other initiatives promote children’s learning and development. Quality improvement initiatives such as our Star Rated License, Child Care Resource and Referral (CCR&R) agencies, T.E.A.C.H. Early Childhood® Scholarship Project, and the Child Care W.A.G.E.S.® Project are designed to improve the quality of programs and services and, in turn,

- 57. benefit children. Although the approaches are different, these programs and initiatives share a similar goal—to promote better outcomes for 2 North Carolina Foundations for Early Learning and Development Purpose of Foundations North Carolina’s Early Childhood Advisory Committee, Division of Child Development and Early Education, and Department of Public Instruction Office of Early Learning worked together to develop Foundations to provide a resource for all programs in the state. Foundations describes Goals for all children’s development and learning, no matter what program they may be served in, what language they speak, what disabilities they may have, or what family circumstances they are growing up in. Teachers and caregivers can turn to Foundations to learn about child development because the document provides age-appropriate Goals and Developmental Indicators for each age level—infant, toddler, and preschooler. Foundations is also intended to be a guide for teaching–not a curriculum or checklist that is used to assess children’s development and learning, but a resource to define the skills and abilities we want to support in the learning experiences we provide for children. The Goals for children can be used by teachers, caregivers, early

- 58. interventionists, home visitors, and other professionals who support and promote children’s development and learning. It is, A Note About Terminology Foundations is designed to be useful to a broad range of professionals who work with children. In this document we refer to “teachers and caregivers.” This terminology includes anyone who works with children—teachers, caregivers, early educators, early interventionists, home visitors, etc. The document also refers to “children” generically, which is intended to include infants, toddlers, and preschool children. however, important to remember that while Foundations can help you determine what is “typical” for children in an age group, the Developmental Indicators may not always describe a particular child’s development. When a child’s development and learning does not seem to fit what is included in the continuum under his/her age level, look at the Developmental Indicators for younger or older age groups to see if they are a better fit for the child. Your goal is to learn what developmental steps the child is taking now, and to meet the individual needs of that child on a daily basis. Foundations can also be used as a resource for parents and other family members. All parents wonder if their child is learning what’s

- 59. needed in order to be successful in school. Parents will find it helpful to review the Goals and Developmental Indicators to learn what most early educators in North Carolina feel are appropriate goals for young children. Finally, Foundations is a useful document for individuals who do not work directly with children, but who support teachers and caregivers in their work. It is important to take stock to see if a program’s learning environment, teaching materials, learning activities, and interactions are supporting children’s development in the areas described 3 North Carolina Foundations for Early Learning and Development in Foundations. Administrators can use Foundations as a guide to evaluate the types of learning experiences provided in their program. Foundations can also be a resource to identify areas where teachers and caregivers need to improve their practices and as a basis for professional development. Training and technical assistance providers should evaluate the support they provide to teachers and caregivers to ensure that the professional development is consistent with the Goals and Developmental Indicators. Furthermore, Foundations can be used as a textbook in higher education courses and a training manual for in-service professional development. In

- 60. summary, Foundations is designed to be a resource for teachers, caregivers, parents, administrators, and professional development providers as we work together to support the learning and development of North Carolina’s youngest children. Organization of This Document This document begins with this Introduction, which provides background information on the use of Foundations. Following the Introduction, you will find the Goals and Developmental Indicators, which describe expectations for what children will learn prior to kindergarten, starting with infancy and covering all ages through kindergarten entry. A glossary with definitions of key terms that are used throughout Foundations is included at the end of the document. The Goals and Developmental Indicators are divided into five domains: • Approaches to Play and Learning (APL) • Emotional and Social Development (ESD) • Health and Physical Development (HPD) • Language Development and Communication (LDC) • Cognitive Development (CD) Because infants’, toddlers’, and preschool children’s bodies, feelings, thinking skills, language, social skills, love of learning, and knowledge all develop together, it is essential

- 61. that we include all five of these domains in Foundations. None of the domains is more or less important than others, and there is some overlap between what is covered in one domain and what’s covered in other domains. This is because children’s development and learning is integrated or interrelated. The progress that a child makes in one domain is related to the progress he or she makes in other domains. For example, as a child interacts with adults (i.e., Social Development), she/he learns new words (i.e., Language Development) that help her/ him understand new concepts (i.e., Cognitive Development). Therefore, it is essential that Foundations address all five domains, and that teachers and caregivers who are using Foundations pay attention to all five domains. At the beginning of each domain section, you will find a domain introduction that describes some of the most important ideas related to the domain. This introductory information helps you understand what aspects of children’s learning and development are included in the domain. The introduction is followed by the Goal and Developmental Indicator Continuum (sometimes called a “Continuum” for short in this document) for each domain. The Continuum for each domain is a chart that shows the Goals for the domain, and the Developmental Indicators related to each Goal for each age level. As the sample chart on the next page shows, North Carolina has elected to arrange our Developmental

- 62. Indicators along a continuum so that all of the Developmental Indicators for the age levels between birth and kindergarten entry are included on the same row. This format allows teachers and caregivers to easily look across the age levels to see the progression that a child might make toward the Goal. 4 North Carolina Foundations for Early Learning and Development The Goals are organized in subdomains or subtopics that fall within the domain. Goals are statements that describe a general area or aspect of development that children make progress on through birth through age five. The Developmental Indicators are more specific statements of expectations for children’s learning and development that are tied to particular age levels. A Goal and Developmental Indicator Continuum is provided for each Goal. 28 North Carolina Foundations for Early Learning and Development Approaches to Play and Learning (APL) Curiosity, Information-Seeking, and Eagerness Goal APL-1: Children show curiosity and express interest in the

- 63. world around them. Developmental Indicators Infants Younger Toddlers Older Toddlers Younger Preschoolers Older Preschoolers • Show interest in others (smile or gaze at caregiver, make sounds or move body when other person is near). APL-1a • Show interest in themselves (watch own hands, play with own feet). APL-1b • React to new sights, sounds, tastes, smells, and touches (stick out tongue at first solid food, turn head quickly when door slams). APL-1c • Imitate what others are doing. APL-1d • Show curiosity about their surroundings (with pointing, facial expressions, words). APL-1e • Show pleasure when

- 64. exploring and making things happen (clap, smile, repeat action again and again). APL-1f • Discover things that interest and amaze them, and seek to share them with others. APL-1g • Show pleasure in new skills and in what they have done. APL-1h • Watch what others are doing and often try to participate. APL-1i • Discover things that interest and amaze them, and seek to share them with others. APL-1j • Communicate interest to others through verbal and nonverbal means (take teacher to the science center to see a new animal). APL-1k • Show interest in a growing range of topics, ideas, and tasks. APL-1l • Discover things that

- 65. interest and amaze them, and seek to share them with others. APL-1m • Communicate interest to others through verbal and nonverbal means (take teacher to the science center to see a new animal). APL-1n • Show interest in a growing range of topics, ideas, and tasks. APL-1o • Demonstrate interest in mastering new skills (e.g., writing name, riding a bike, dance moves, building skills). APL-1p ➡➡ ➡ ➡ Domain refers to the broad area of learning or development that is being addressed Subdomain defines areas within each domain

- 66. more specifically Goal provides a broad statement of what children should know or be able to do Developmental Indicator provides more specific information about what children should know or be able to do at Goal and Developmental Indicator Continuum is the chart that shows the Goal and corresponding Developmental Indicators for each age level 5 North Carolina Foundations for Early Learning and Development The Developmental Indicators are grouped into five age groups or levels: Infants, Younger Toddlers, Older Toddlers, Younger Preschoolers, and Older Preschoolers. The age levels or groups are intended as a guide to help the reader know where to start when using each Goal and Developmental Indicator Continuum.

- 67. Generally, the Developmental Indicators describe expectations that many children will reach toward the end of their respective age level. They are not, however, hard and fast requirements or expectations for what children should be able to do at the end of the age level. The fact that there is overlap across the age levels shows that what children know and are able to do at one age is closely related to what they know and are able to do at the previous and the next age levels. Most children will reach many, but not necessarily all, of the Developmental Indicators that are listed for their age level; some will exceed the Developmental Indicators for their age level well before they are chronologically at the upper end of the age range; and others may never exhibit skills and knowledge described for a particular age level. Each Goal and Developmental Indicator Continuum is designed to help teachers and caregivers identify where an individual child might be on the learning continuum described in the Developmental Indicators, and to easily see what might have come before and what might come after the child’s current level of development. The Developmental Indicators are numbered so that it is easier to find specific items. The identification system is the same for all Developmental Indicators across all five domains. First, there is an abbreviation of the domain where the Developmental Indicator is

- 68. found (APL for Approaches to Play and Learning in the sample chart). The abbreviation is followed by a number that indicates what Goal the Developmental Indicator is associated with (1 for Goal 1 in the sample chart). Finally, each of the Developmental Indicators for each Goal has a letter that reflects the order of the item. The first indicator in the infant age level begins with the letter “a,” the second indicator begins with the letter “b,” etc. All subsequent indicators are assigned a letter in alphabetical order. (The sample chart shows Developmental Indicators “a” through “p”). The numbering system is simply a way to help teachers and caregivers communicate more easily about the Developmental Indicators (i.e., so they can refer to specific indicators without having to write or say the whole indicator), and does not Developmental Indicator Numbering System Domain Abbreviation Goal Number Indicator Letter APL ESD HPD LDC

- 69. CD 1 – 15 a - z Age Periods The Developmental Indicators are divided into overlapping age levels shown below. These age ranges help the reader know where to start when using the Developmental Indicators. They describe expectations many children will reach toward the end of the respective age level, but are not requirements for what children should know and be able to do at the end of the age period. • Infants: birth to 12 months • Younger Toddlers: 8–21 months • Older Toddlers: 18–36 months • Younger Preschoolers: 36–48 months • Older Preschoolers: 48–60+ months 6 North Carolina Foundations for Early Learning and Development imply that any Developmental Indicator is more important or should come before others within the same age level. Occasionally, the same Developmental Indicators apply to two or more age levels. Arrows are used to show where these Developmental Indicators repeat. The final resources included in Foundations

- 70. are the strategies that are provided at the end of each Goal and Developmental Indicator Continuum. These strategies provide ideas for how teachers and caregivers can support children’s development and learning in the areas described in the Developmental Indicators. They are a guide for the types of teaching practices and interactions adults can use to foster children’s progress on the Developmental Indicators. The list includes strategies that can be used to promote the learning and development of all children, and some strategies that are specifically designed to provide ideas on how to work with Dual Language Learners and children with disabilities. The strategies that give specific ideas for accommodations and ways to promote second-language learning may be particularly helpful for teachers working with these groups of children. Most of the strategies are practices that can be carried out as part of a child’s everyday activities. They are not intended to be an exhaustive list of how teachers can support children’s growth and development, but are a place to start when planning activities to support children’s progress. How to Use Foundations To get a general idea of what is included in Foundations, we suggest that you begin by reading the entire document cover to cover. This will help you get a sense of each section and how the various pieces fit together.

- 71. Once you have reviewed Foundations as a whole, you are then ready to focus on the children in your care. Included within each Goal is a set of Developmental Indicators that explain what behaviors or skills to look for according to the age of the child. Check the age level to see which Developmental Indicators (infants, younger toddlers, older toddlers, younger preschoolers, or older preschoolers) might apply to the children you work with, and study those indicators to know what is typical for your children. It may be helpful to start by focusing on one domain at a time. Foundations describes what children at different stages of development often are able to do toward the end of the age period. You will probably notice that children in your group regularly do some of the things listed for their age level. They may just be starting to show some of the abilities, and they may not yet do some of the things described. This is normal. Use the Developmental Indicators to think about next steps for each child in your group. Then consider the natural moments during the day that might offer chances for children to take these next steps. What activities might you plan? What materials might you add to the environment? For children with disabilities or special needs who may not be at the same level as other children their age, use the same process described above: think about next steps for these children by considering their current level of development and how they might develop next.

- 72. Next, consider the strategies listed after the Development Indicators. They can help you think about how to use a natural moment or everyday learning opportunity to address specific areas of children’s development and learning. Many of these strategies can be carried out with no special equipment. Choose strategies that seem most likely to help the children you teach and care for take their 7 North Carolina Foundations for Early Learning and Development next steps. Sometimes the Developmental Indicators for a child’s age level do not seem to describe how a particular child is developing right now. This may happen whether or not a child has a disability. When this happens, look at guidelines for younger or older age groups as appropriate. Your goal is always to learn what developmental steps the child is taking now. Then you can choose strategies to support those next steps. Many strategies for children with disabilities are suggested. Be creative and find ways to adapt other strategies. Families and other professionals can suggest additional ideas. Finally, seek additional professional development to help you use the document effectively. Foundations is designed to be a useful resource for teachers and caregivers and provides a wealth of useful information

- 73. that can be used to improve the quality of care provided to children. It is not, however, intended to be used alone, without additional resources, and does not replace the need for continued professional development. Supervisors, mentors, college instructors, and technical assistant providers offer important support for teachers and caregivers using Foundations. It is important, therefore, to follow the steps described above to use Foundations and to also seek additional information and professional development in order to use the document effectively. Goals and Developmental Indicators SHOULD Be Used To … • Promote development of the whole child, including physical, emotional-social, language, cognitive development, and learning characteristics. • Provide a common set of expectations for children’s development and, at the same time, validate the individual differences that should be expected in children. • Promote shared responsibility for children’s early care and education. • Emphasize the importance of play as an instructional strategy that promotes learning in early childhood programs.

- 74. • Support safe, clean, caring, and effective learning environments for young children. • Support appropriate teaching practices and provide a guide for gauging children’s progress. • Encourage and value family and community involvement in promoting children’s success. • Reflect and value the diversity that exists among children and families served in early care and education programs across the state. Goals and Developmental Indicators Should NOT Be Used To … • Stand in isolation from what we know and believe about children’s development and about quality early education programs. • Serve as an assessment checklist or evaluation tool to make high-stakes decisions about children’s program placement or entry into kindergarten. • Limit a child’s experiences or exclude children from learning opportunities for any reason. • Set up conflicting expectations and requirements for programs.

- 75. • Decide that any child has “failed” in any way. • Emphasize child outcomes over program requirements. 8 North Carolina Foundations for Early Learning and Development Domains, Subdomains, and Goals Overview Approaches to Play and Learning (APL) Curiosity, Information-Seeking, and Eagerness • Goal APL-1: Children show curiosity and express interest in the world around them. • Goal APL-2: Children actively seek to understand the world around them. Play and Imagination • Goal APL-3: Children engage in increasingly complex play. • Goal APL-4: Children demonstrate creativity, imagination, and inventiveness. Risk-Taking, Problem-Solving, and Flexibility • Goal APL-5: Children are willing to try new and challenging experiences . • Goal APL-6: Children use a variety of strategies to solve problems. Attentiveness, Effort, and Persistence