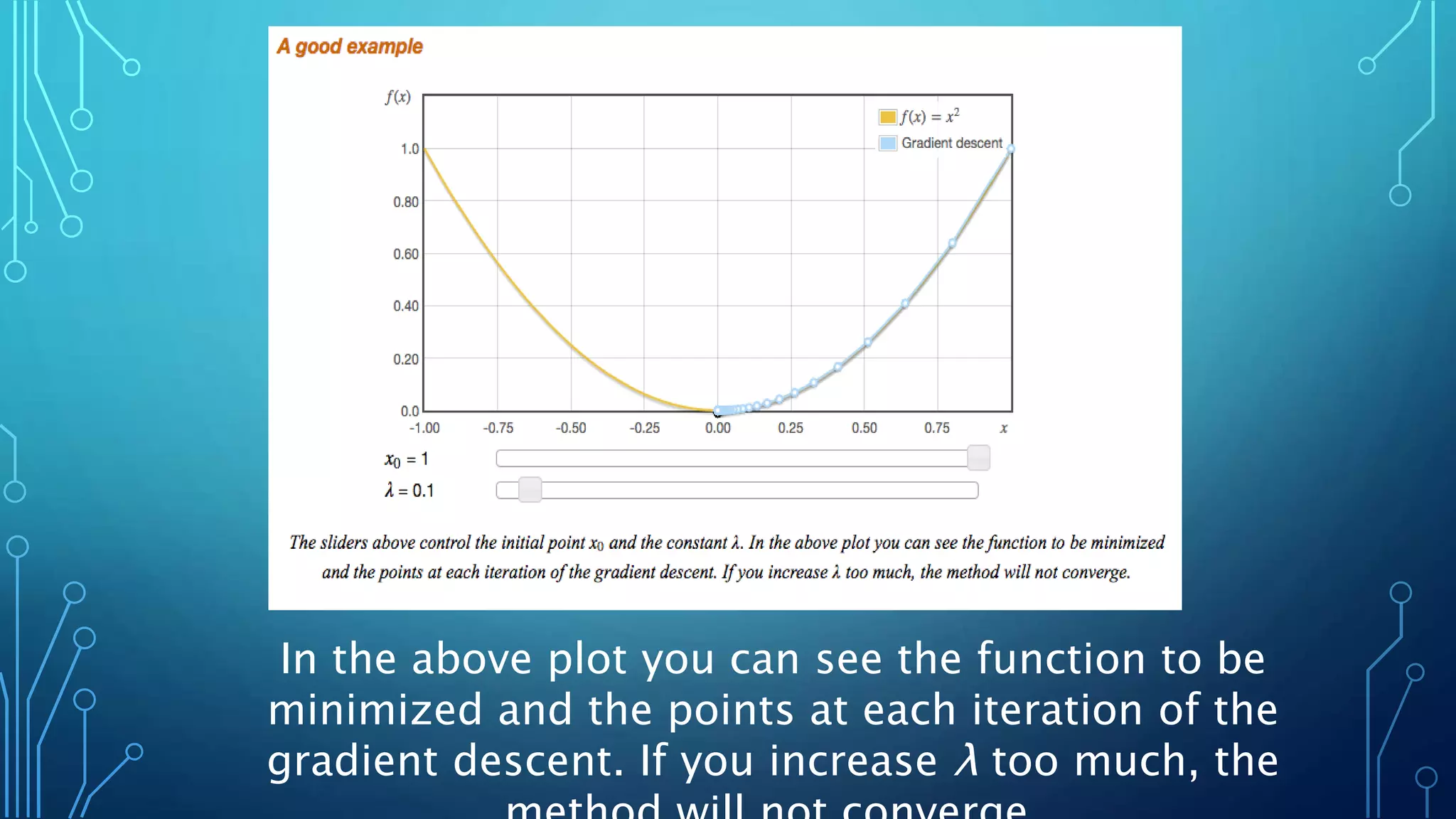

This document discusses the steepest descent method, also called gradient descent, for finding the nearest local minimum of a function. It works by iteratively moving from each point in the direction of the negative gradient to minimize the function. While effective, it can be slow for functions with long, narrow valleys. The step size used in gradient descent is important - too large will diverge it, too small will take a long time to converge. The Lipschitz constant of a function's gradient provides an upper bound for the step size to guarantee convergence.