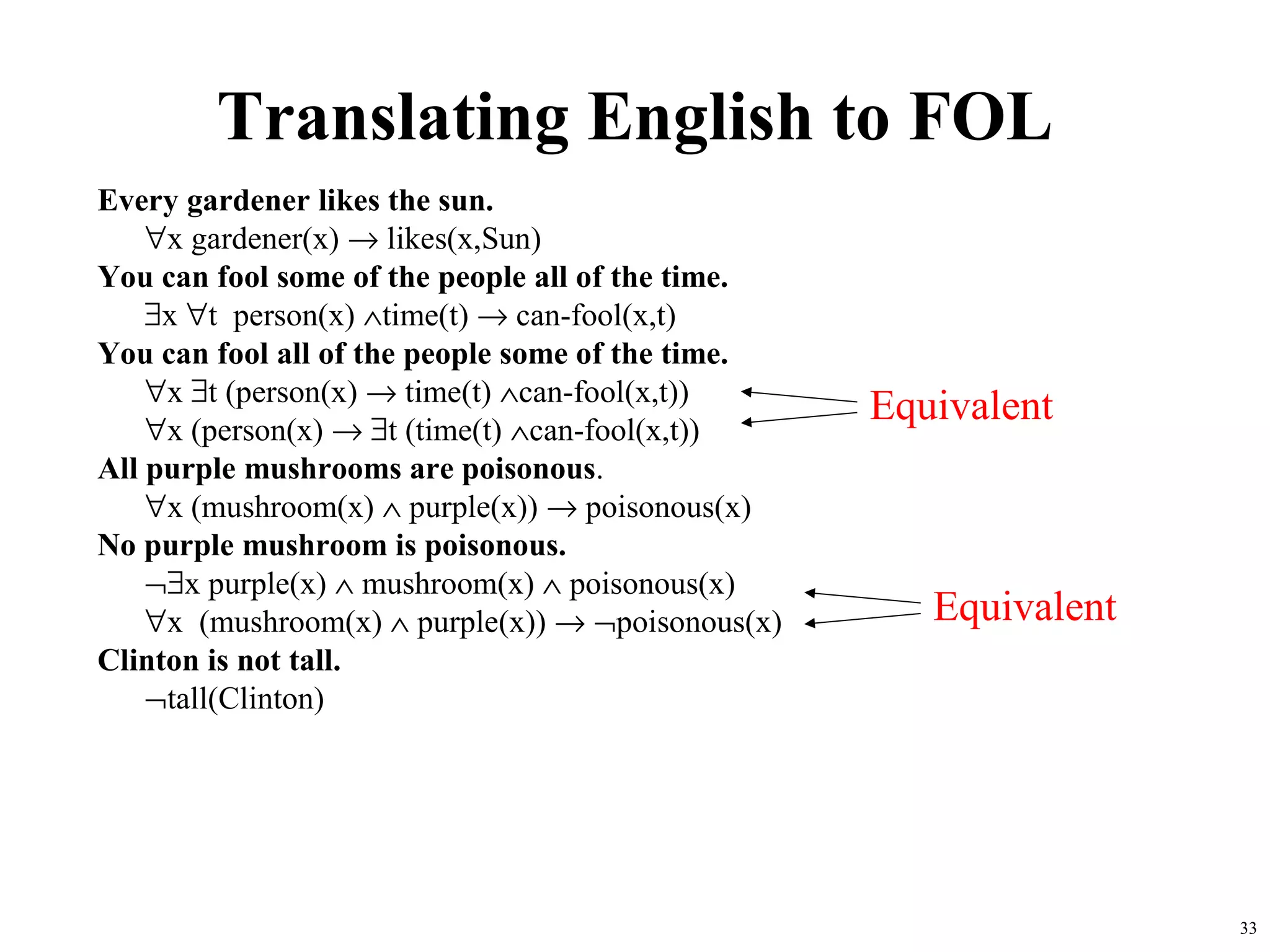

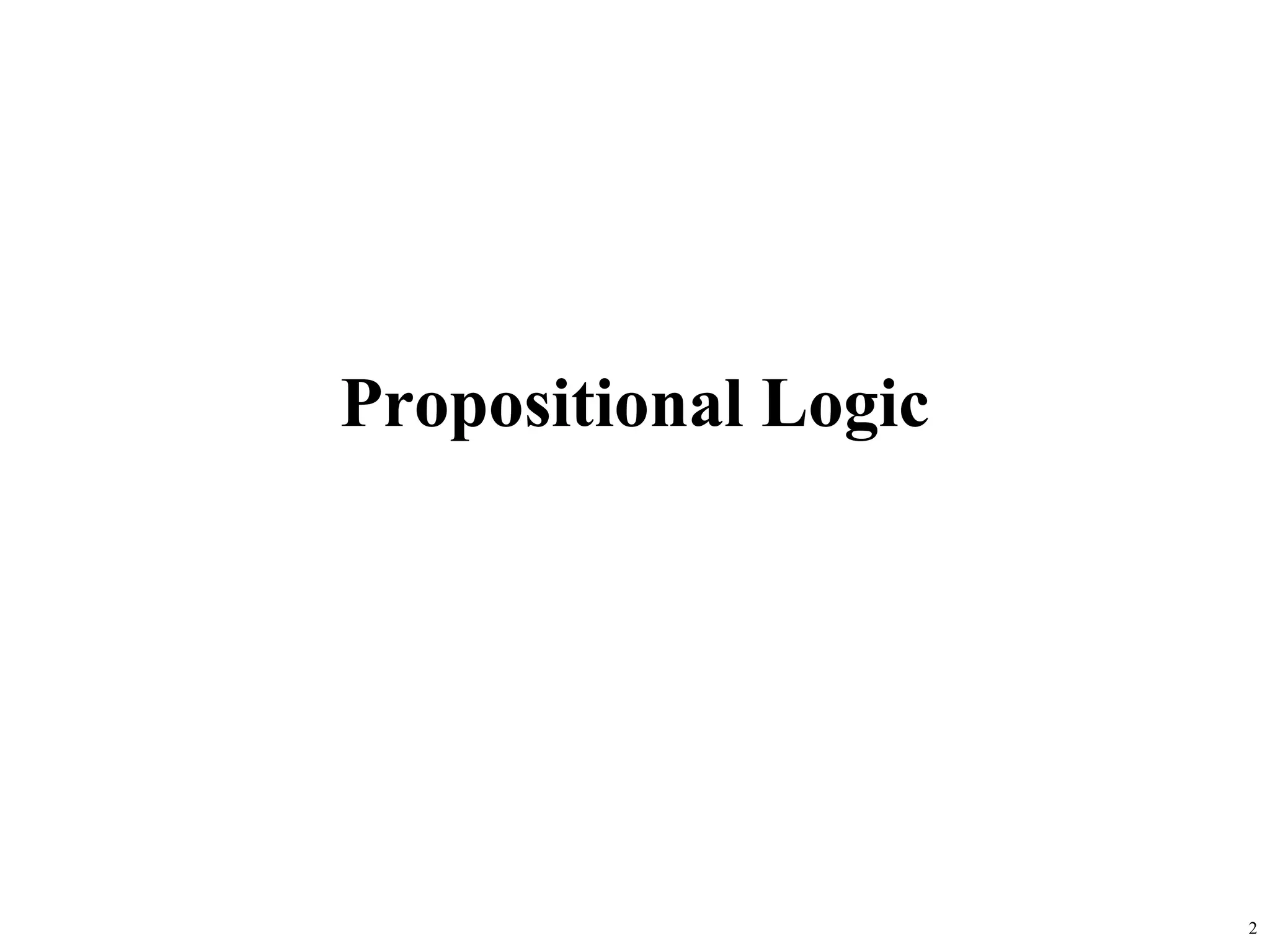

This document provides an introduction to propositional logic and first-order logic. It defines propositional logic, including propositional variables, connectives like conjunction and disjunction, and the laws of propositional logic. It then introduces first-order logic, which adds quantifiers, variables, functions, and predicates to represent objects, properties, and relations in a domain. First-order logic allows for more expressive statements about individuals and generalizations than propositional logic alone.

![Propositional logic

• Proposition : A proposition is classified as a declarative

sentence which is either true or false.

eg: 1) It rained yesterday.

• Propositional symbols/variables: P, Q, S, ... (atomic

sentences)

• Sentences are combined by Connectives:

∧ ...and [conjunction]

∨ ...or [disjunction]

⇒ ...implies [implication / conditional]

⇔ ..is equivalent [biconditional]

¬ ...not [negation]

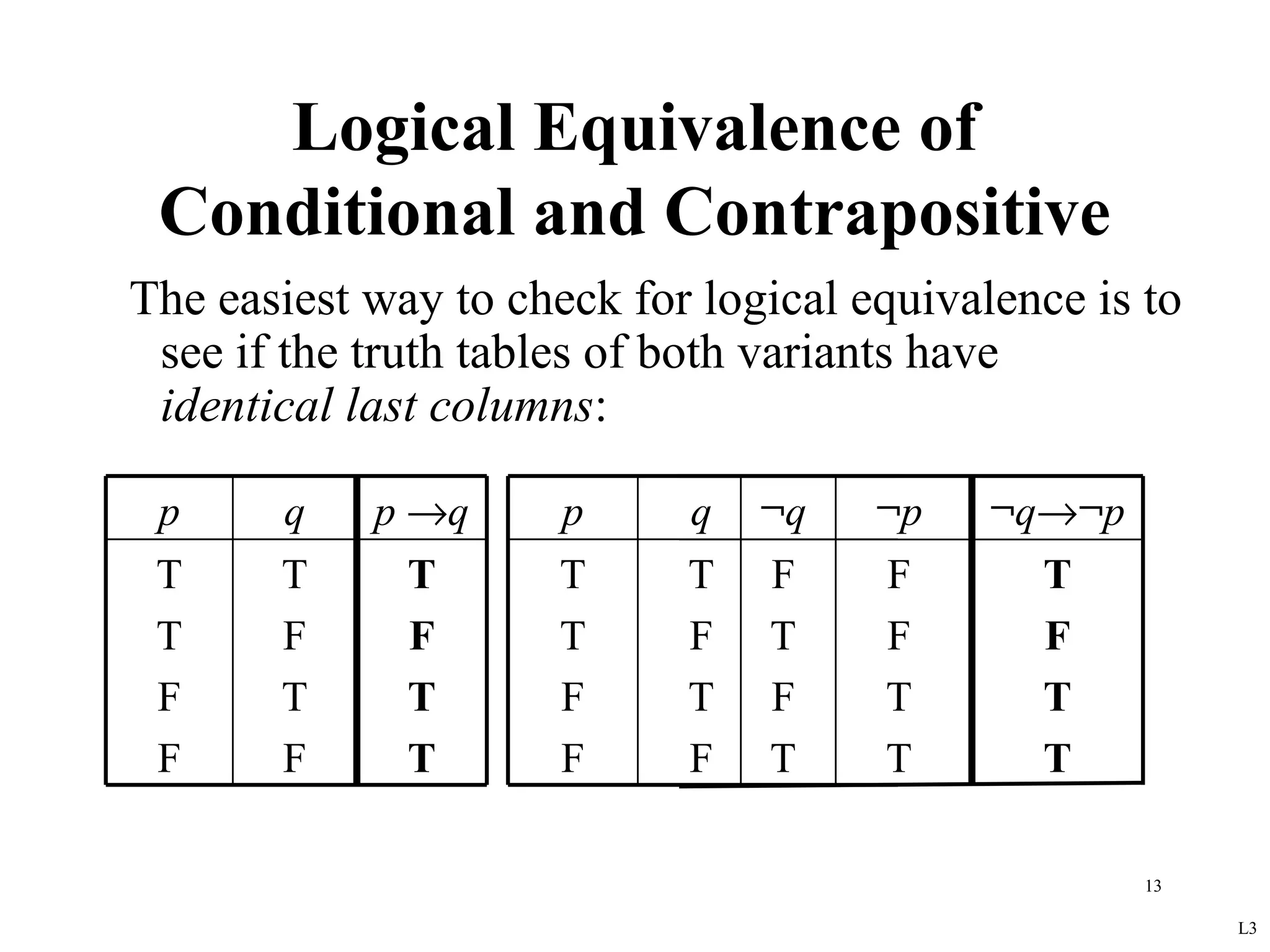

• Literal: atomic sentence or negated atomic sentence

3](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/c10logic1-121109070410-phpapp02/75/Propositional-And-First-Order-Logic-3-2048.jpg)

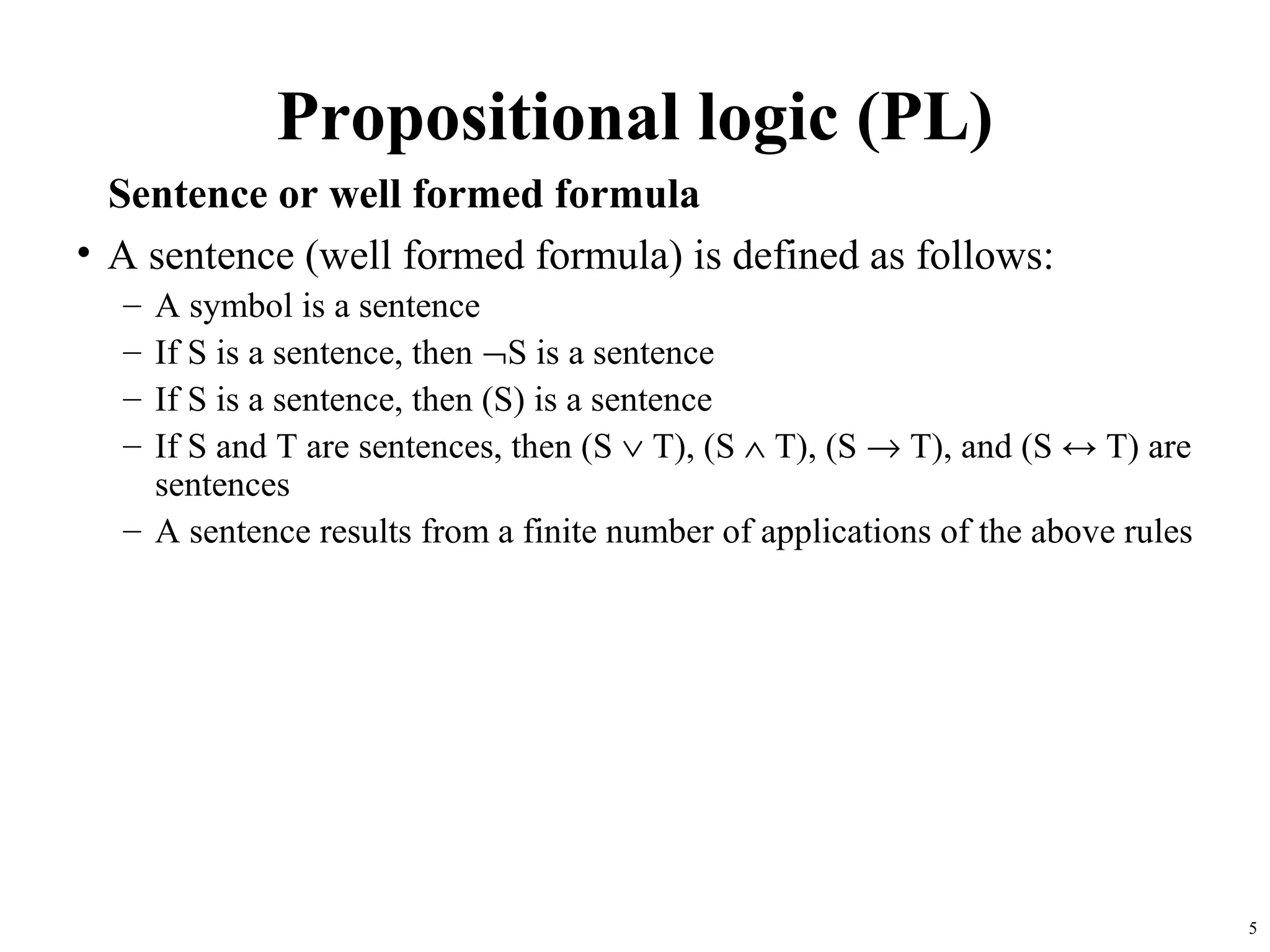

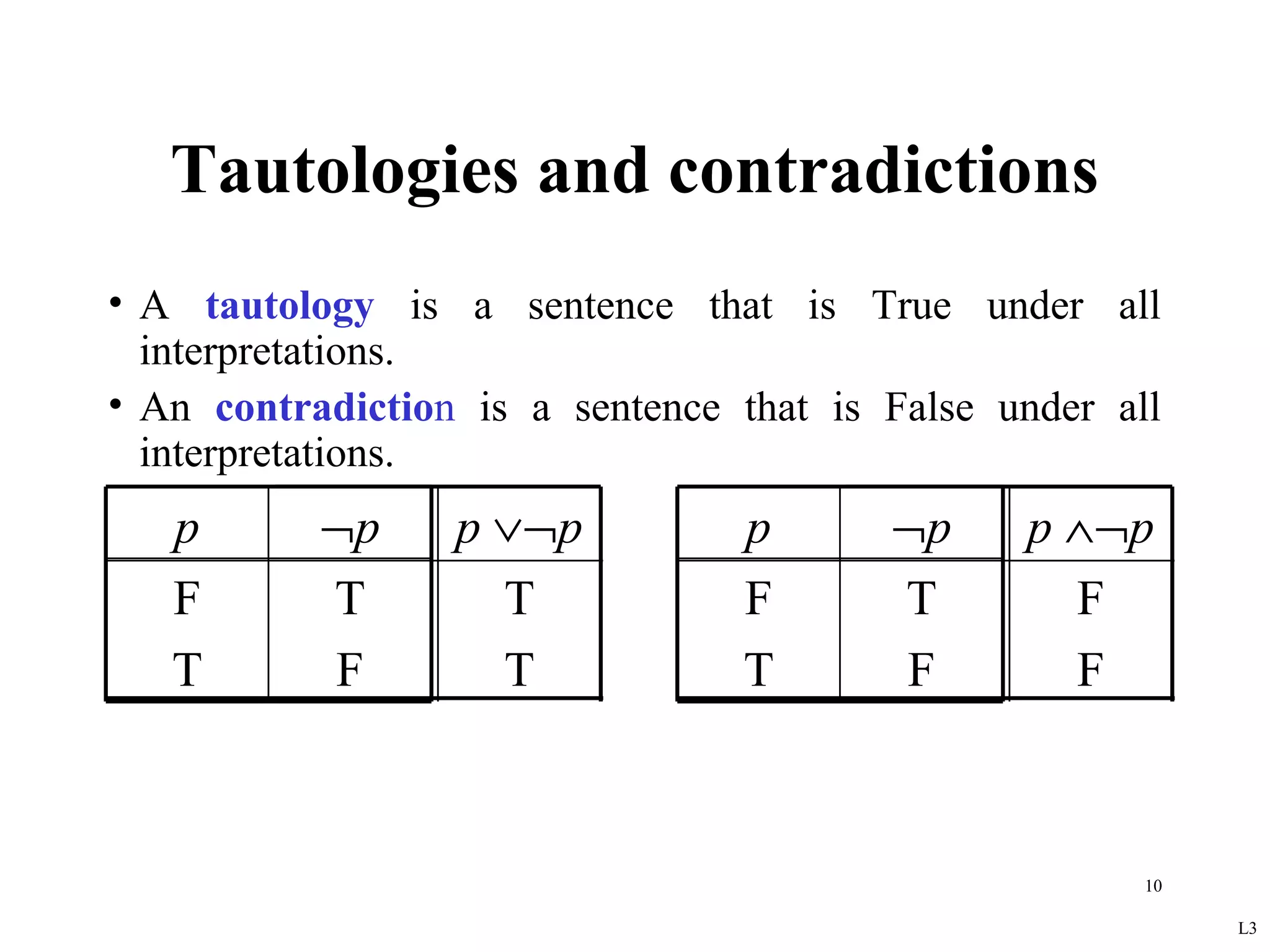

![Tautology by truth table

p q ¬p p ∨q ¬p ∧(p ∨q ) [¬p ∧(p ∨q )]→q

T T F T F T

T F F T F T

F T T T T T

F F T F F T

11

L3](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/c10logic1-121109070410-phpapp02/75/Propositional-And-First-Order-Logic-9-2048.jpg)

![Propositional Logic - one last proof

Show that [p ∧ (p → q)] → q is a tautology.

We use ≡ to show that [p ∧ (p → q)] → q ≡ T.

[p ∧ (p → q)] → q

≡ [p ∧ (¬p ∨ q)] → q substitution for →

≡ [(p ∧ ¬p) ∨ (p ∧ q)] → q distributive

≡ [ F ∨ (p ∧ q)] → q complement

≡ (p ∧ q) → q identity

≡ ¬(p ∧ q) ∨ q substitution for →

≡ (¬p ∨ ¬q) ∨ q DeMorgan’s

≡ ¬p ∨ (¬q ∨ q ) associative

≡ ¬p ∨ T complement

≡T identity

11/09/12

12](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/c10logic1-121109070410-phpapp02/75/Propositional-And-First-Order-Logic-10-2048.jpg)