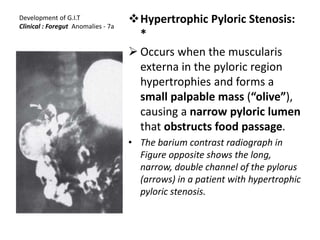

The document provides an overview of a lecture on gastrointestinal tract development and malformations. It discusses hypertrophic pyloric stenosis, which causes projectile, non-bilious vomiting in infants after feeding due to muscular hypertrophy in the pyloric region. It also discusses anomalies of the gallbladder and cystic duct that can occur, as well as biliary atresia, which is defined as obliteration of the extrahepatic and intrahepatic bile ducts. The types and causes of jaundice are examined, along with investigations such as liver function tests and imaging, and management approaches.