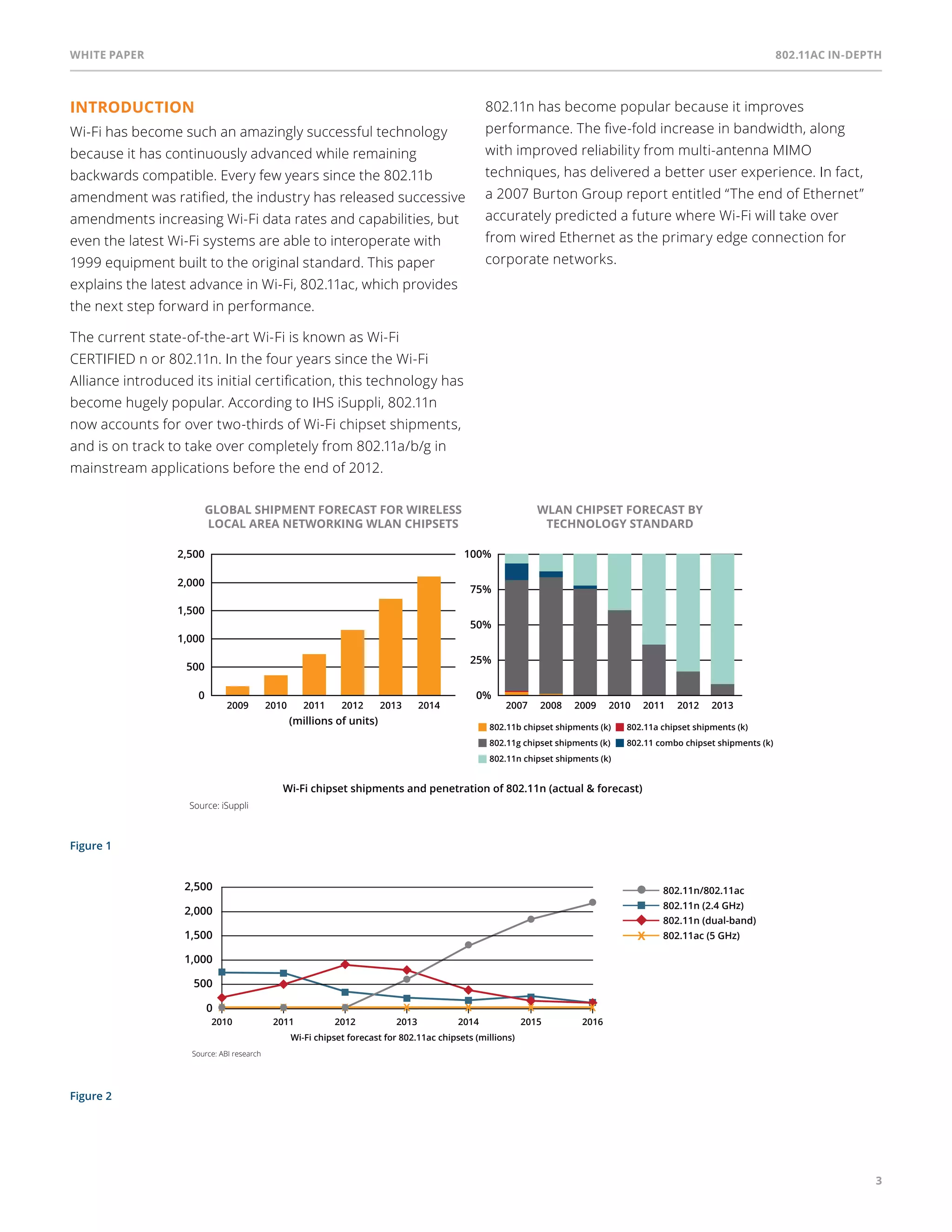

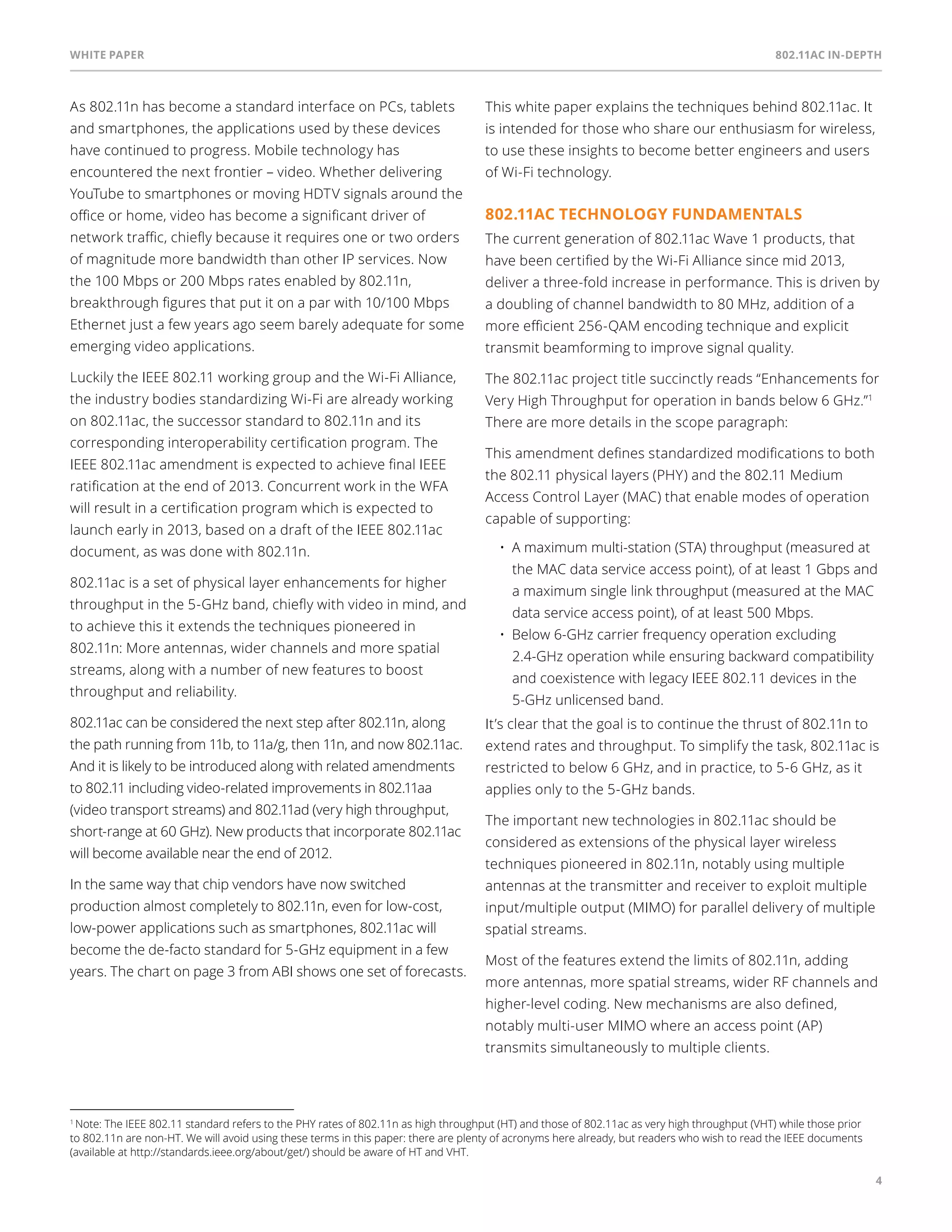

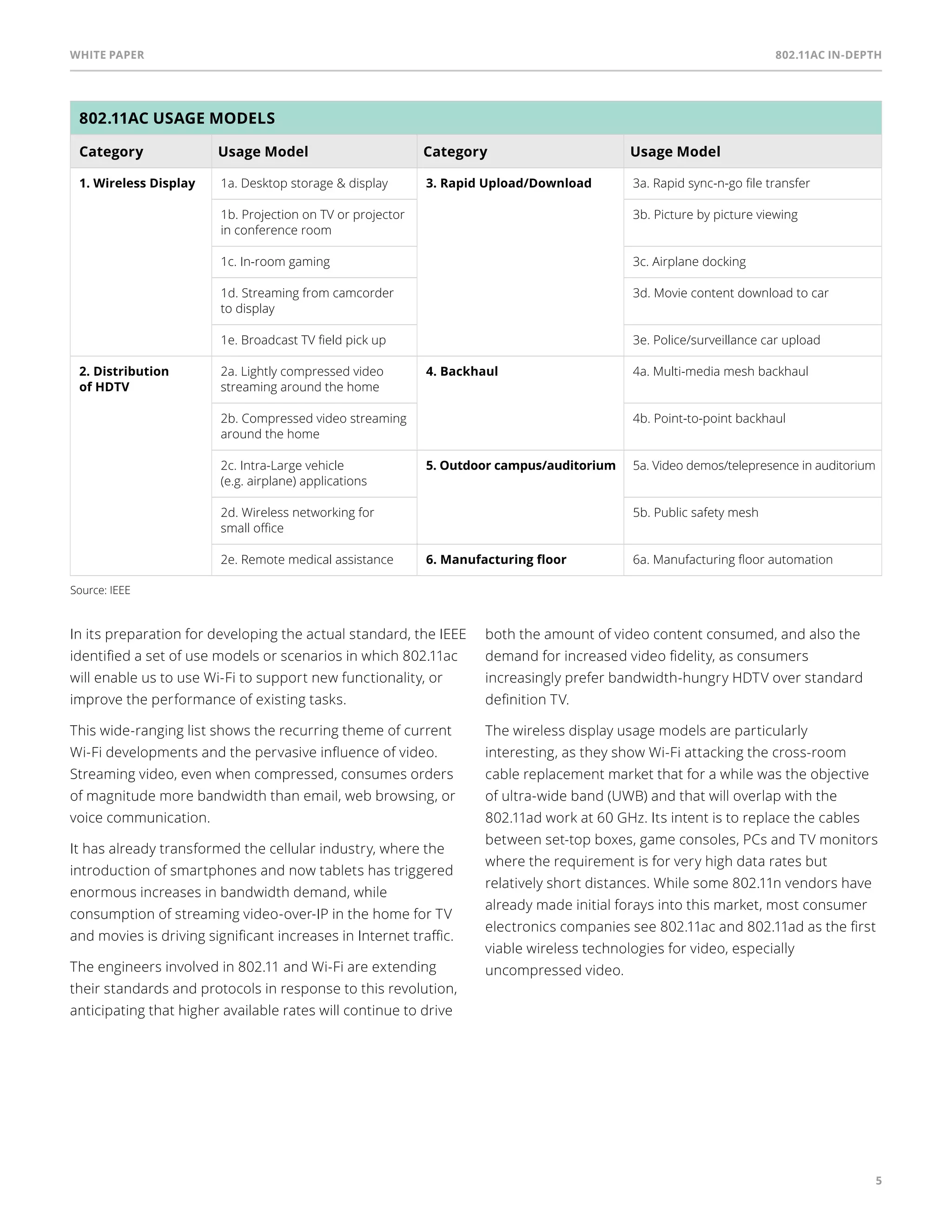

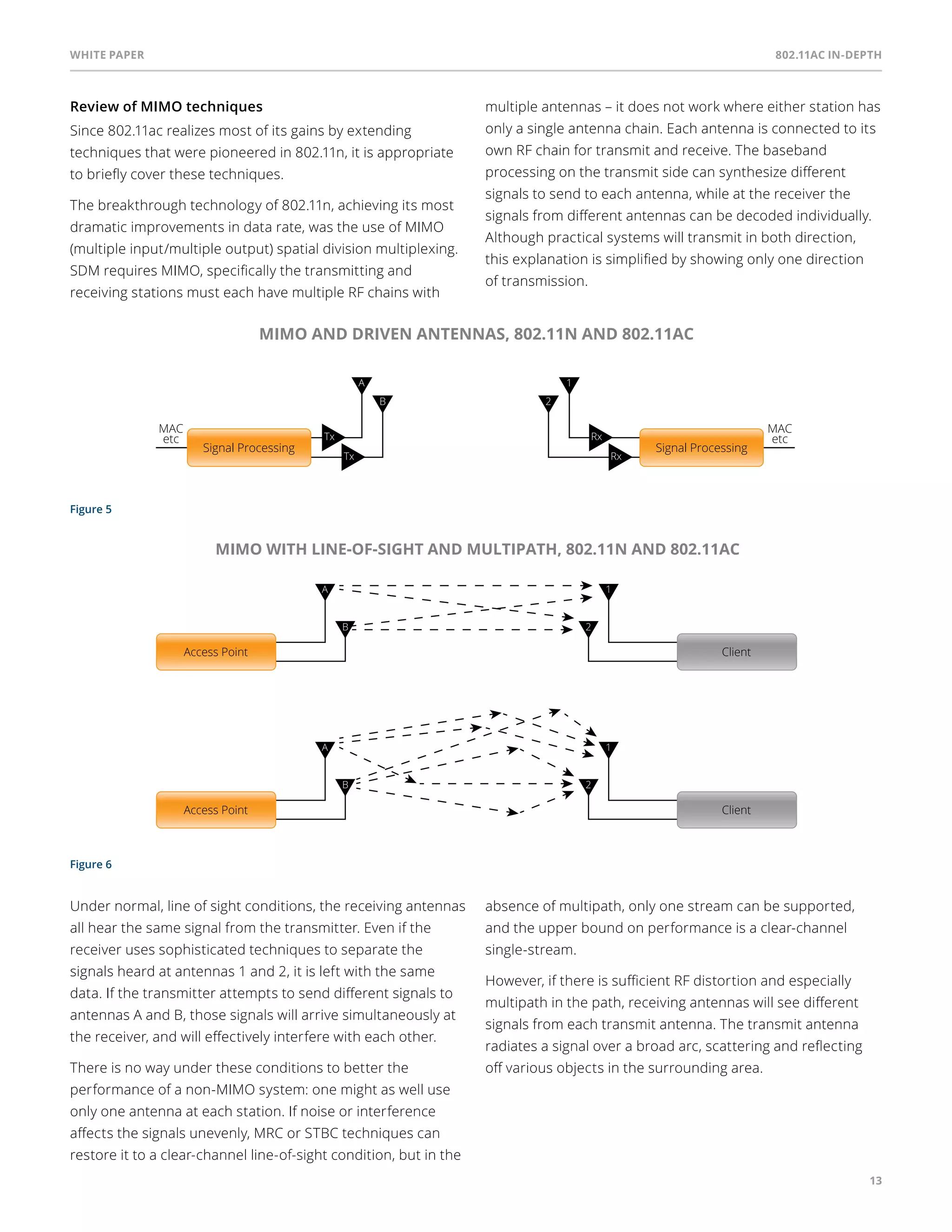

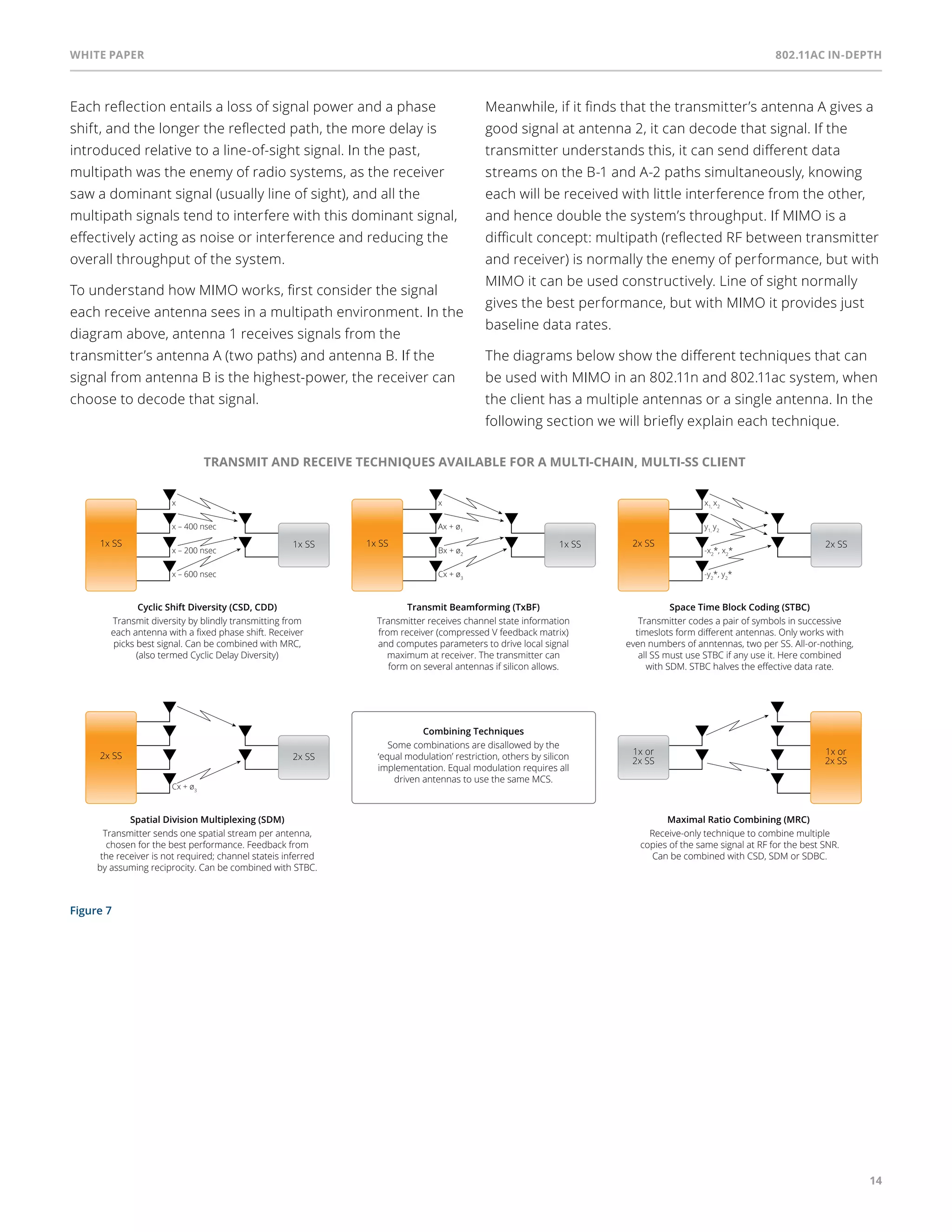

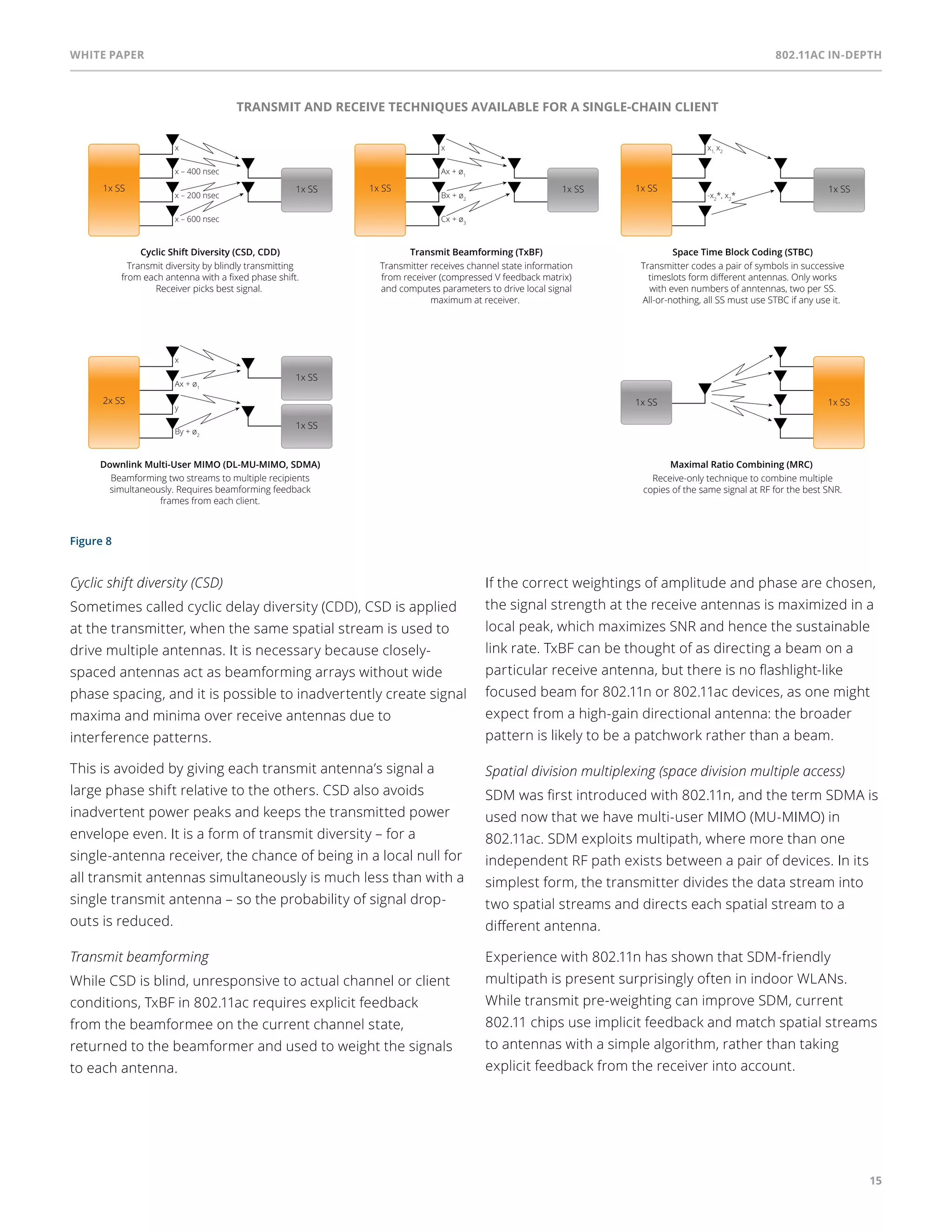

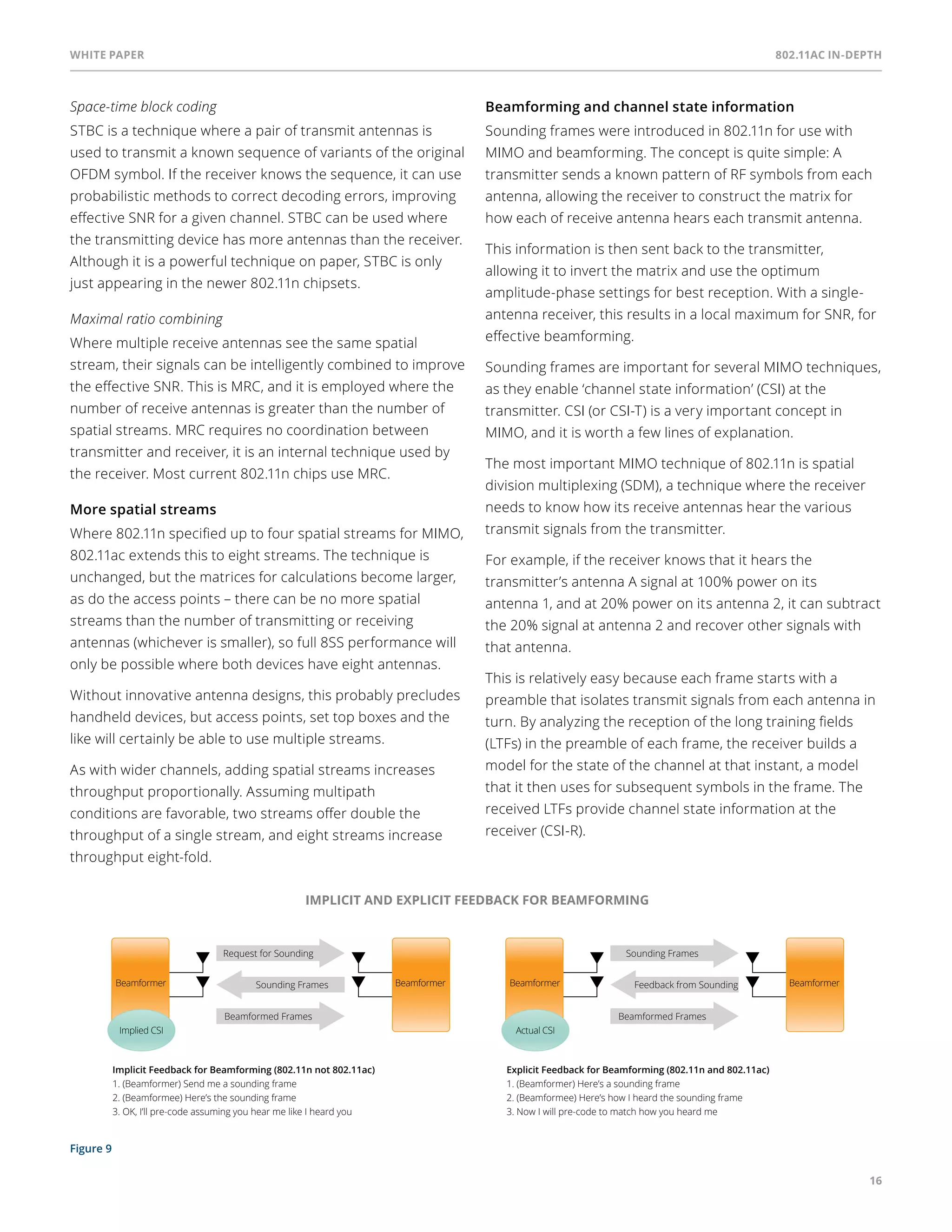

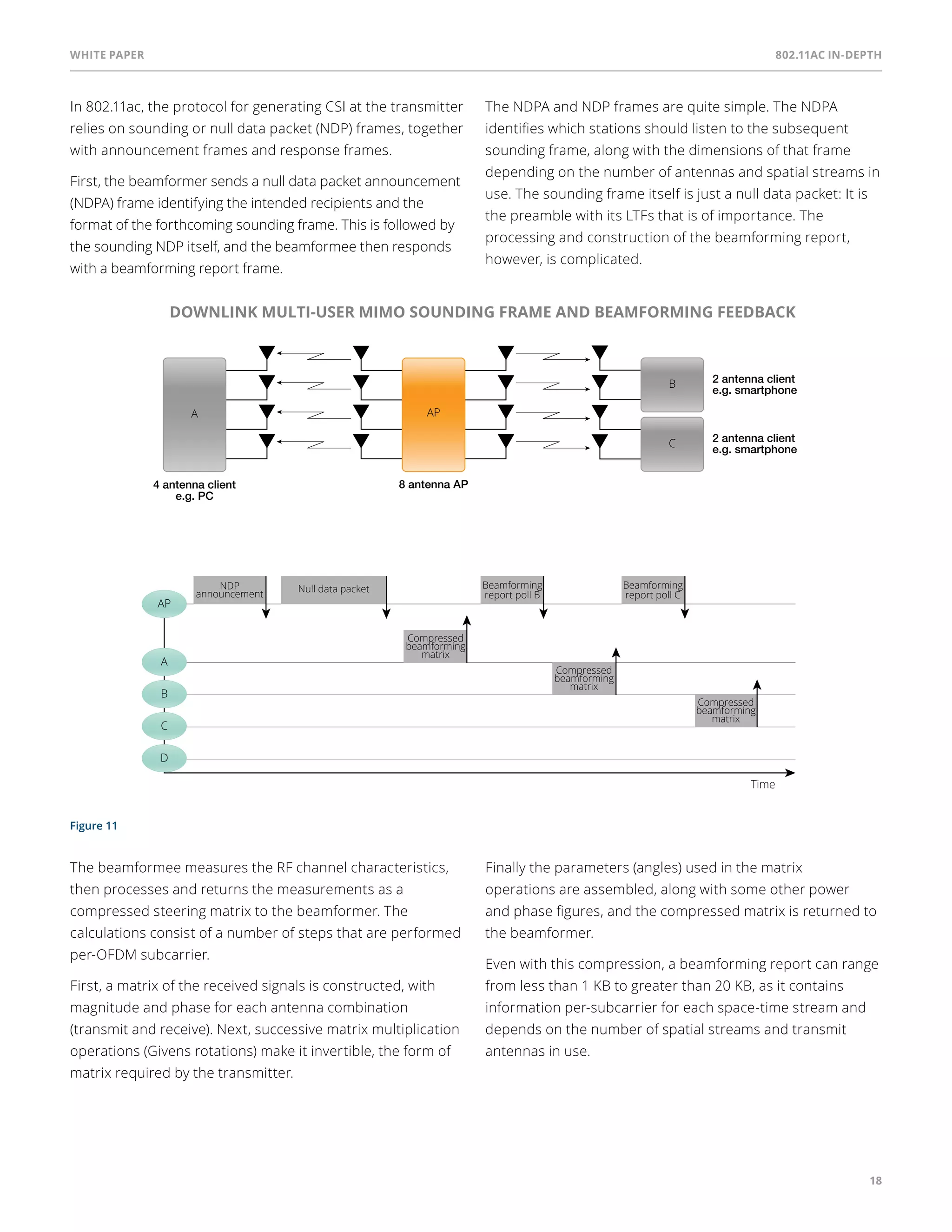

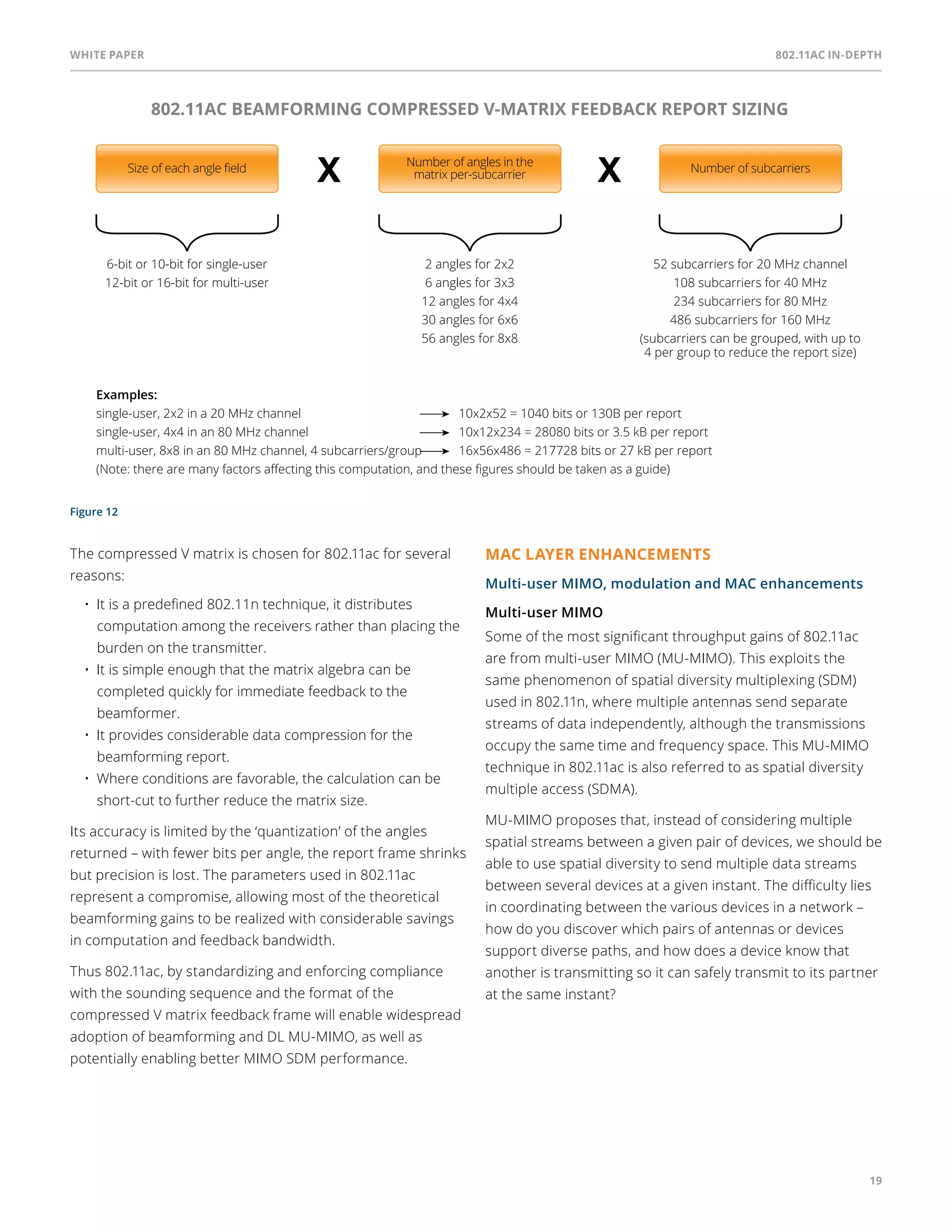

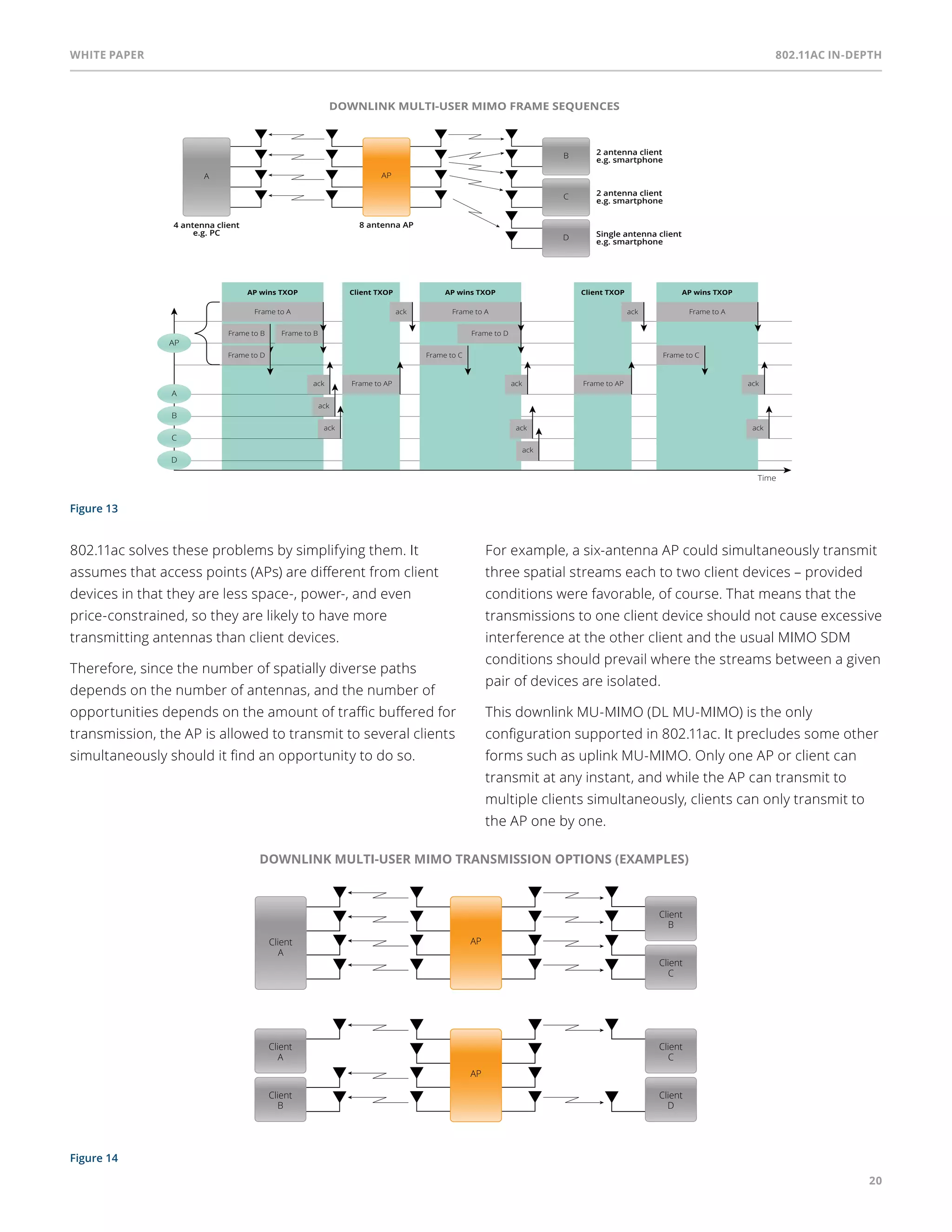

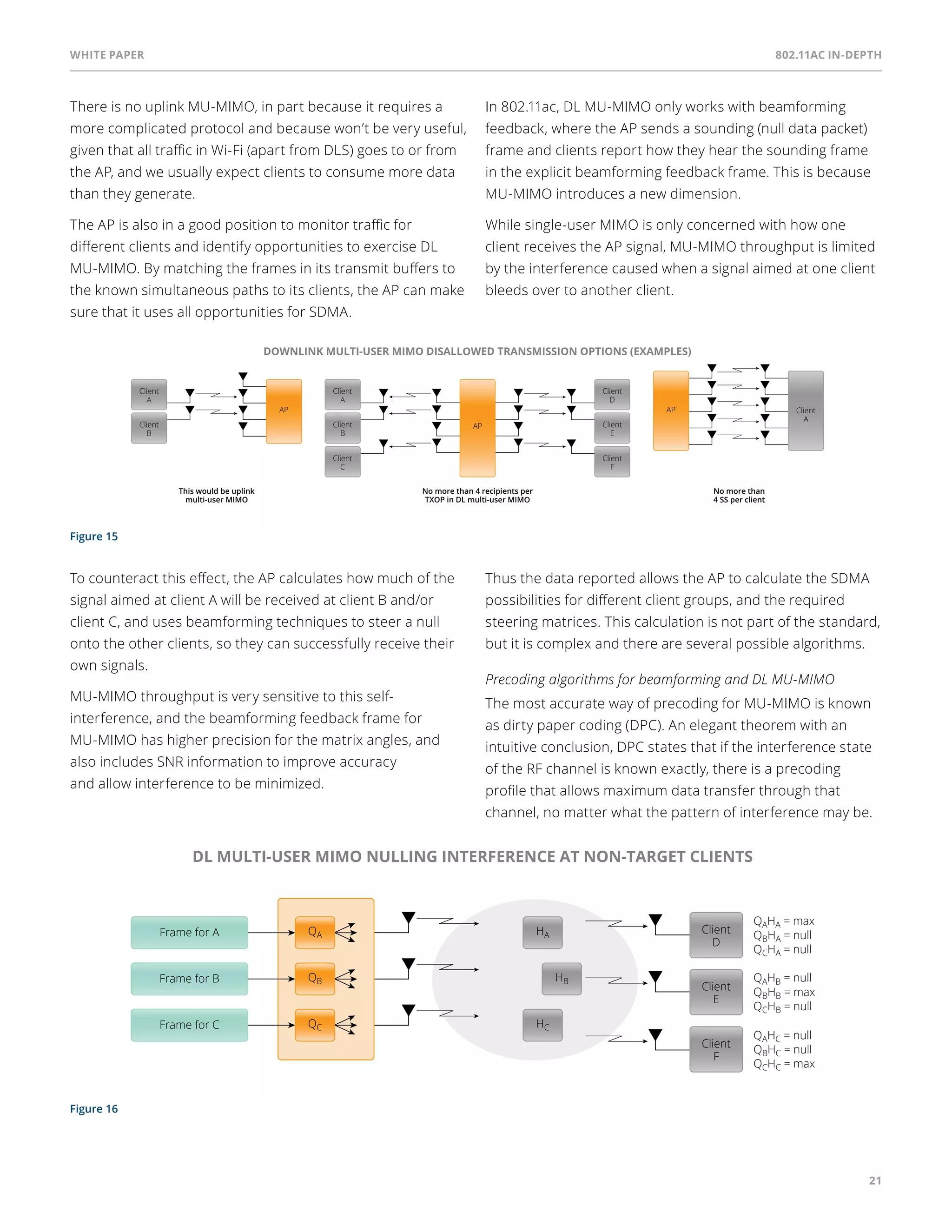

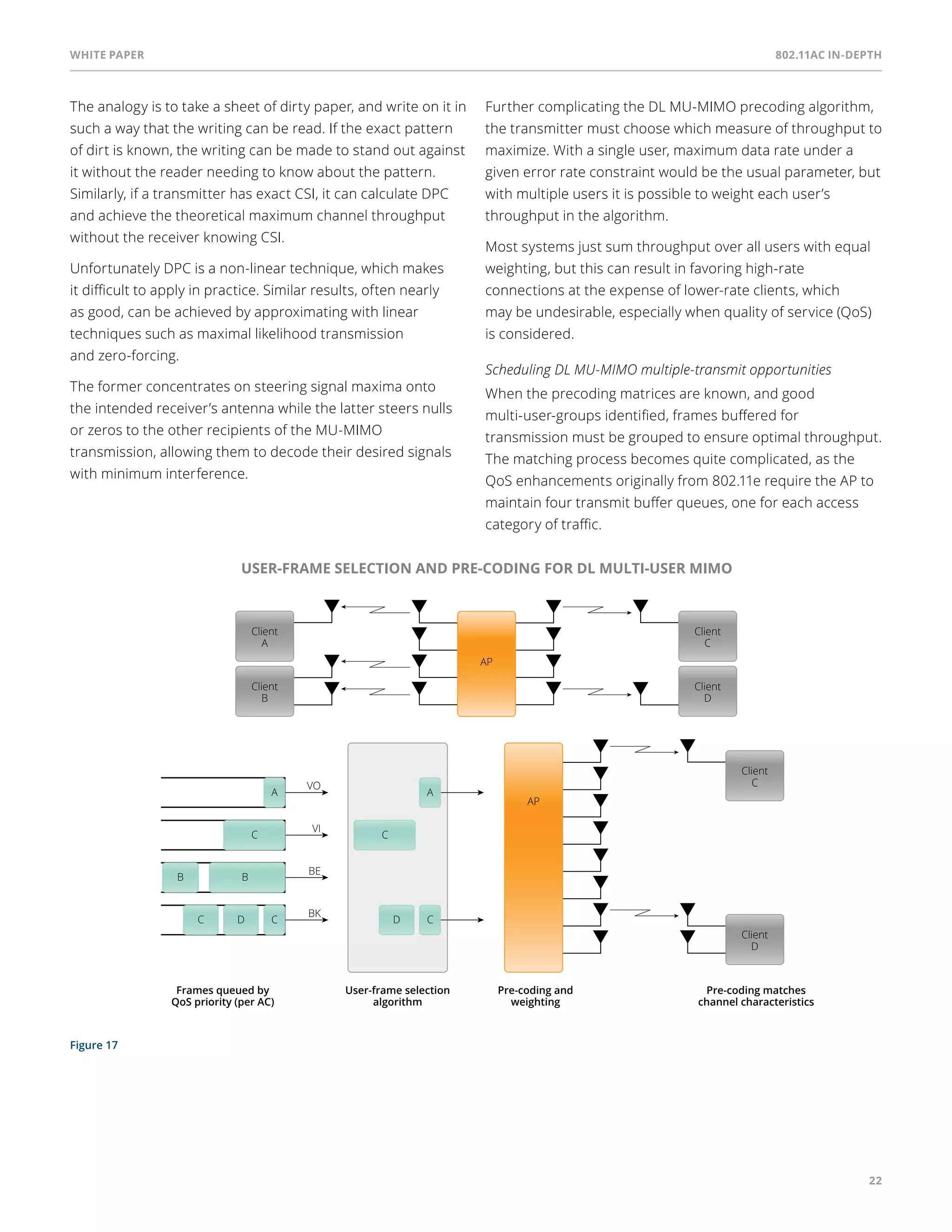

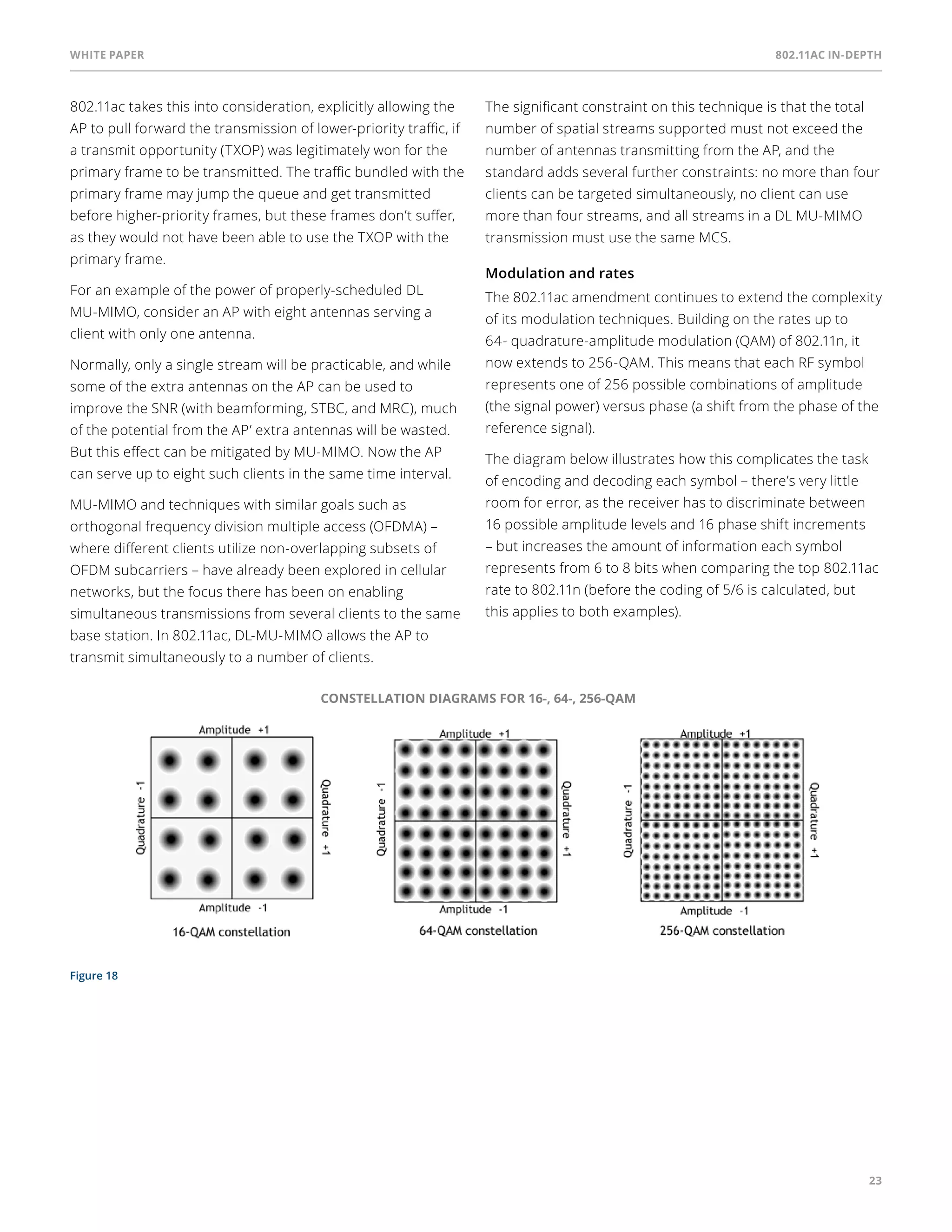

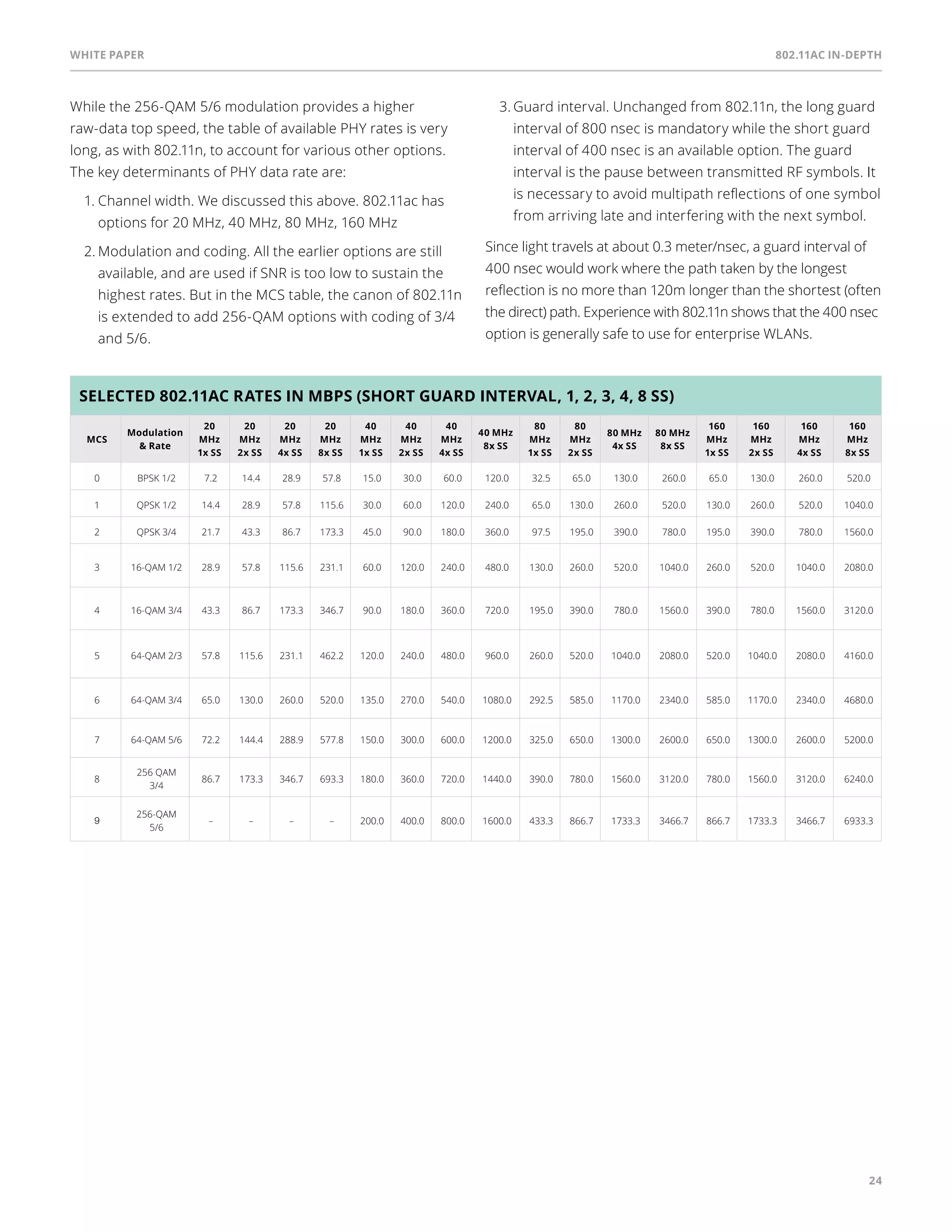

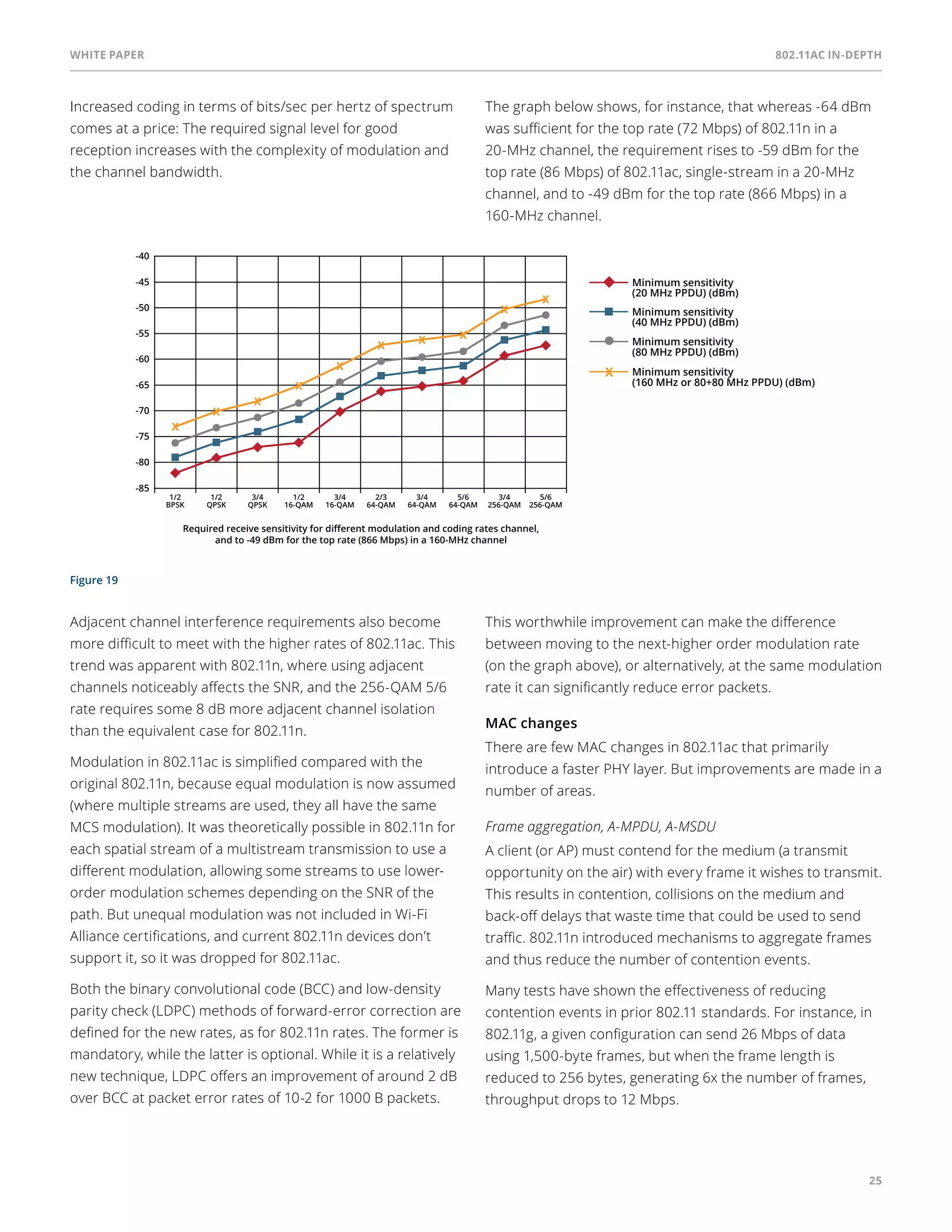

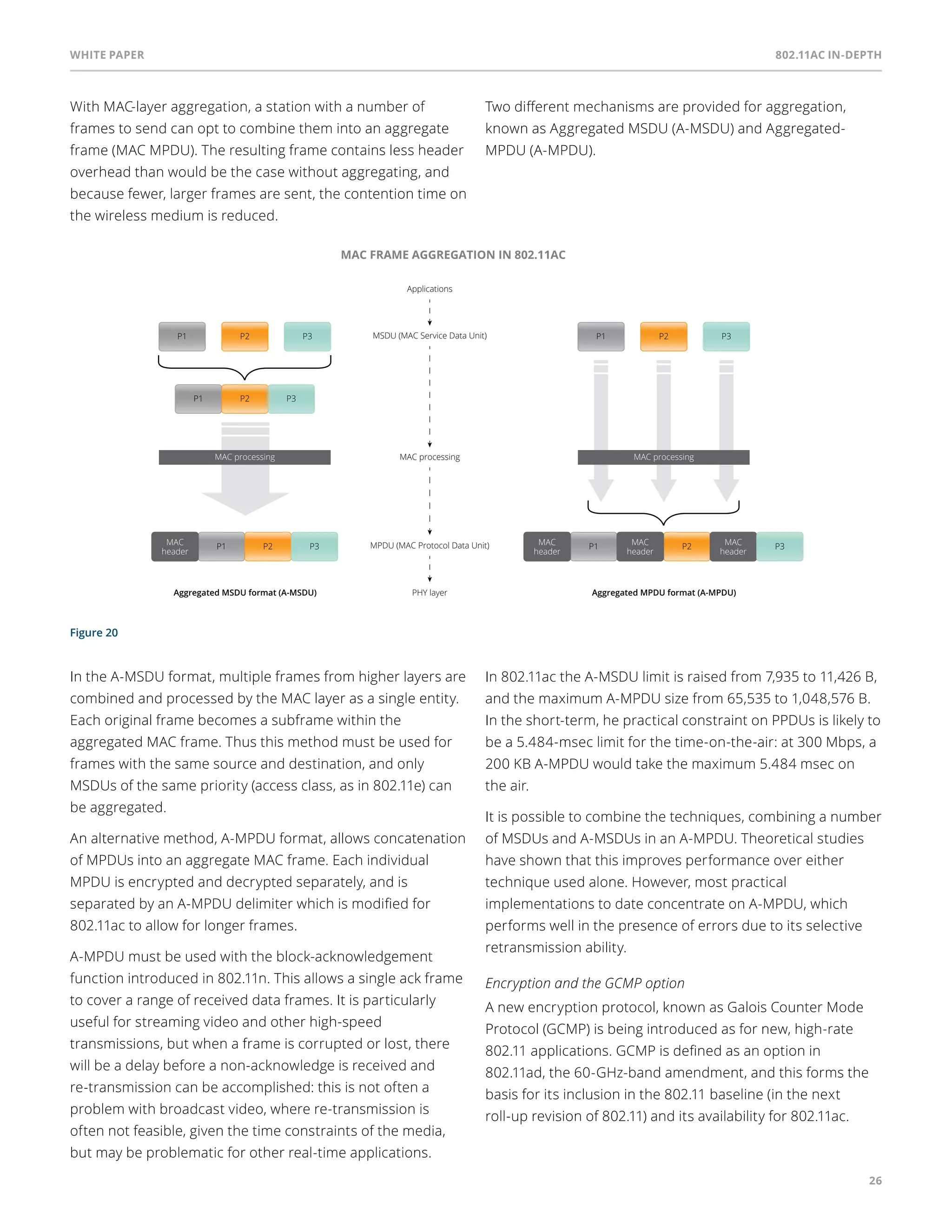

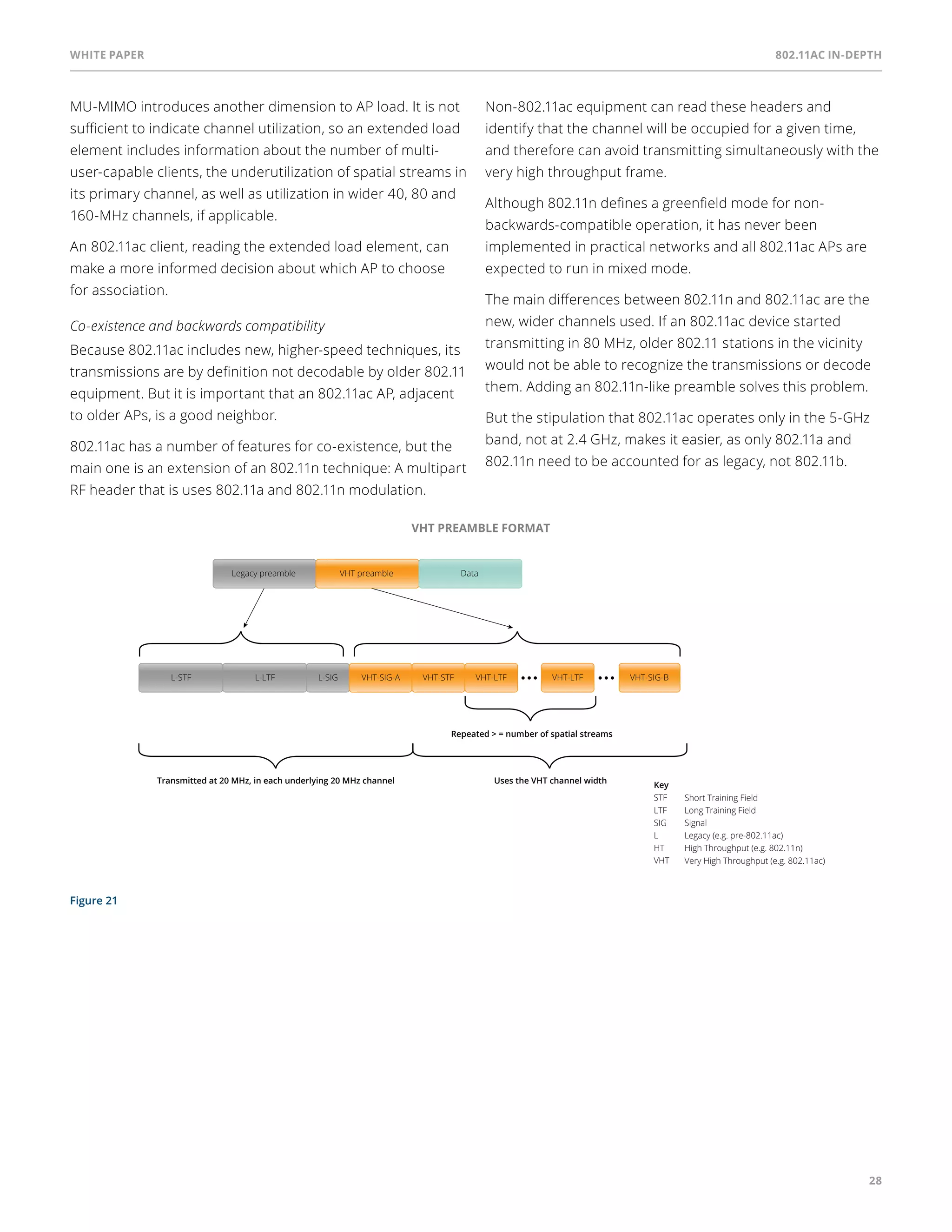

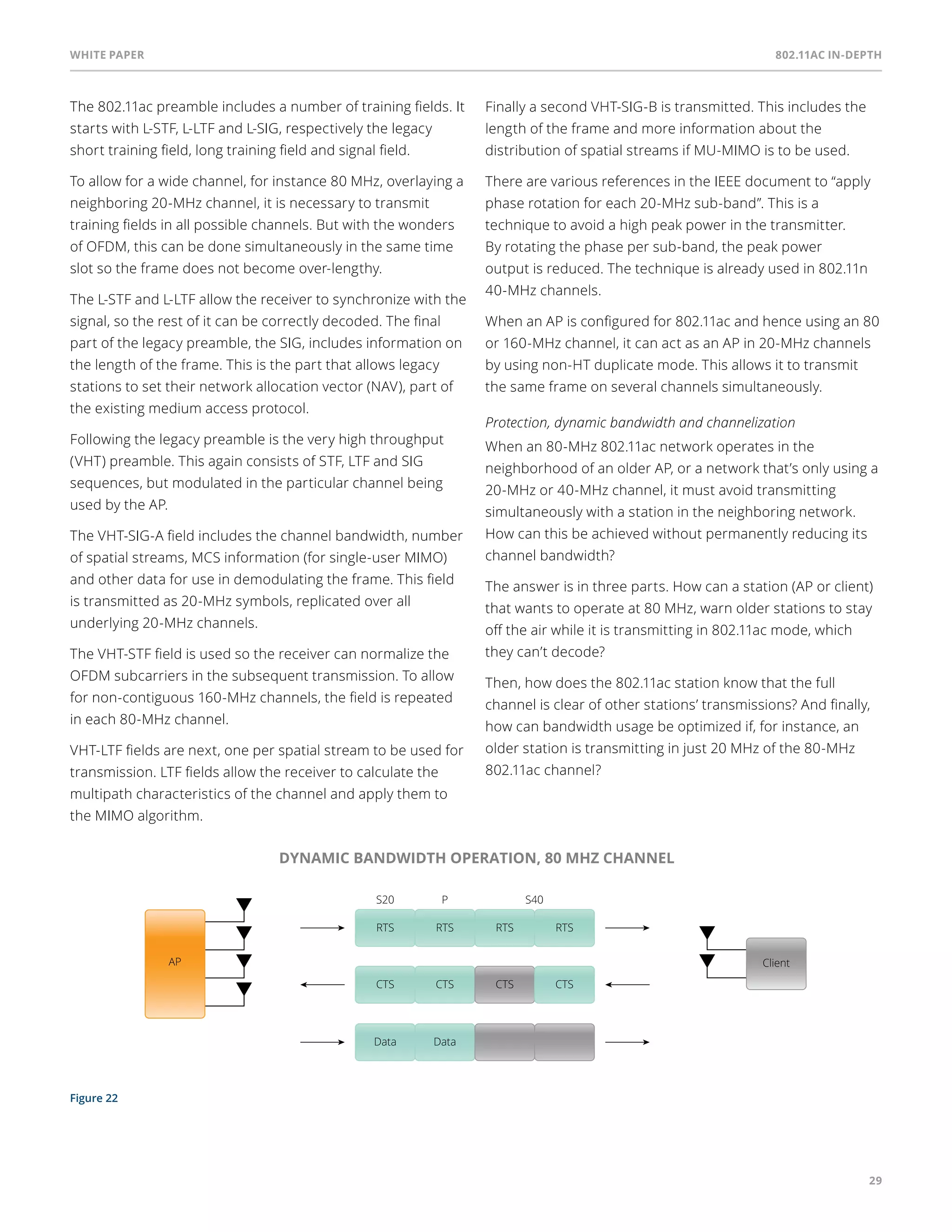

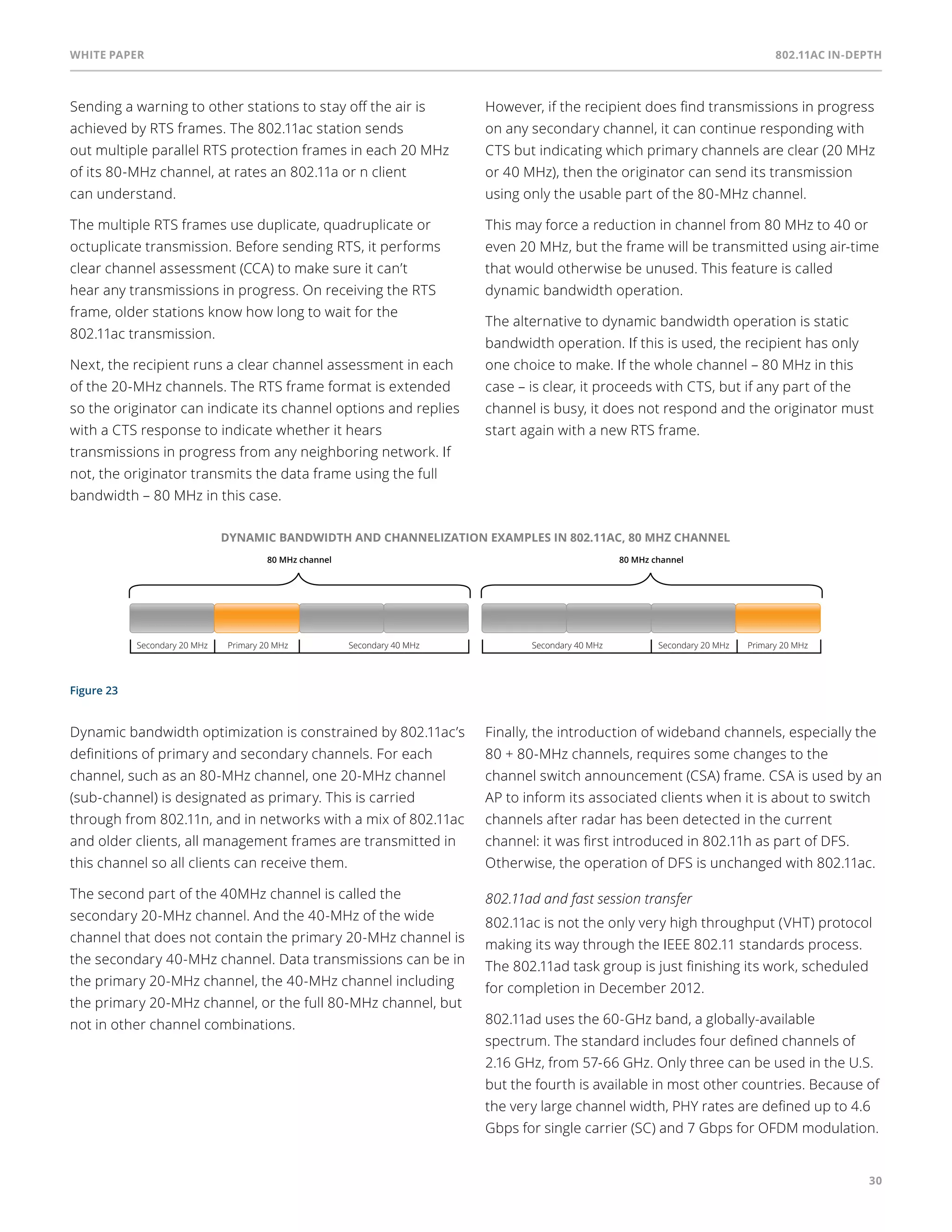

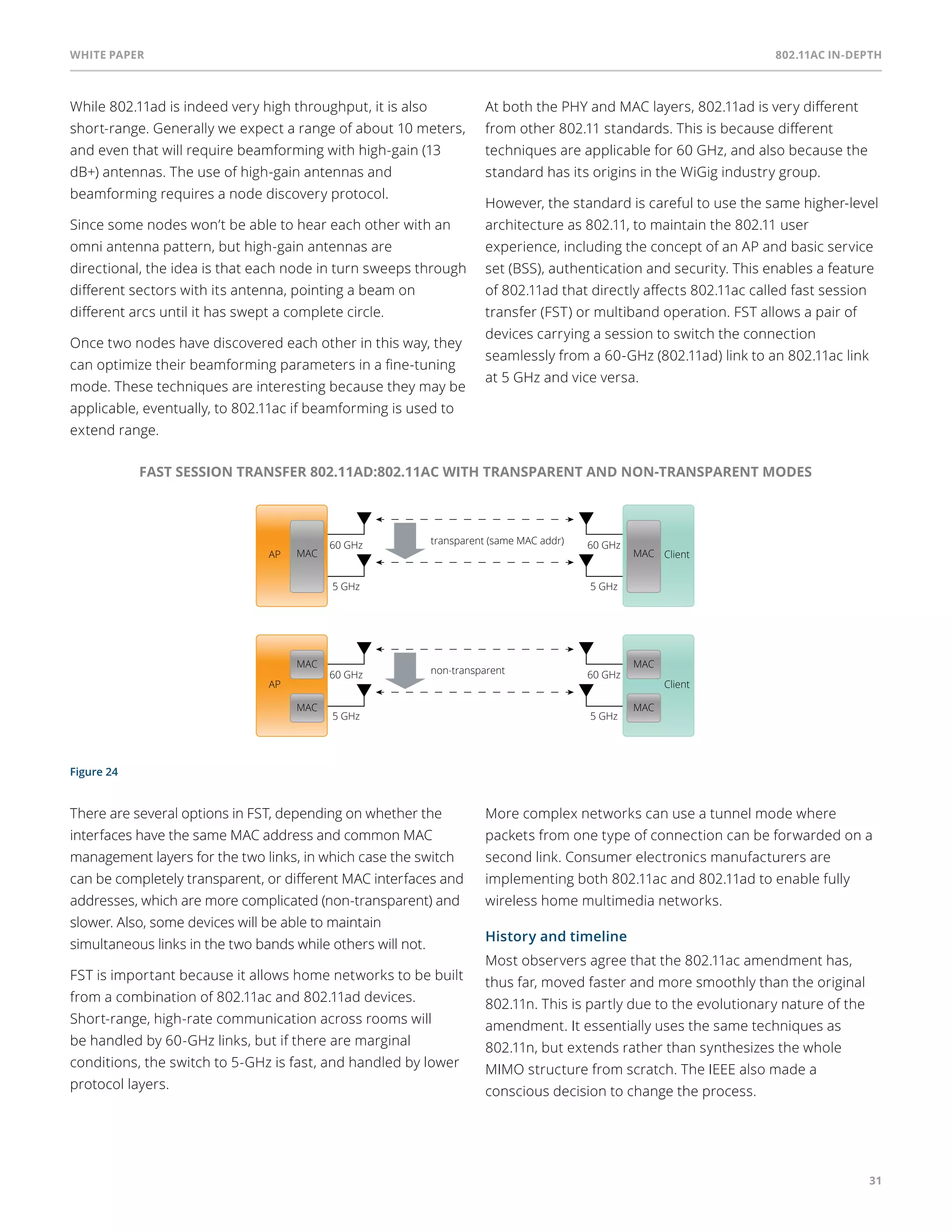

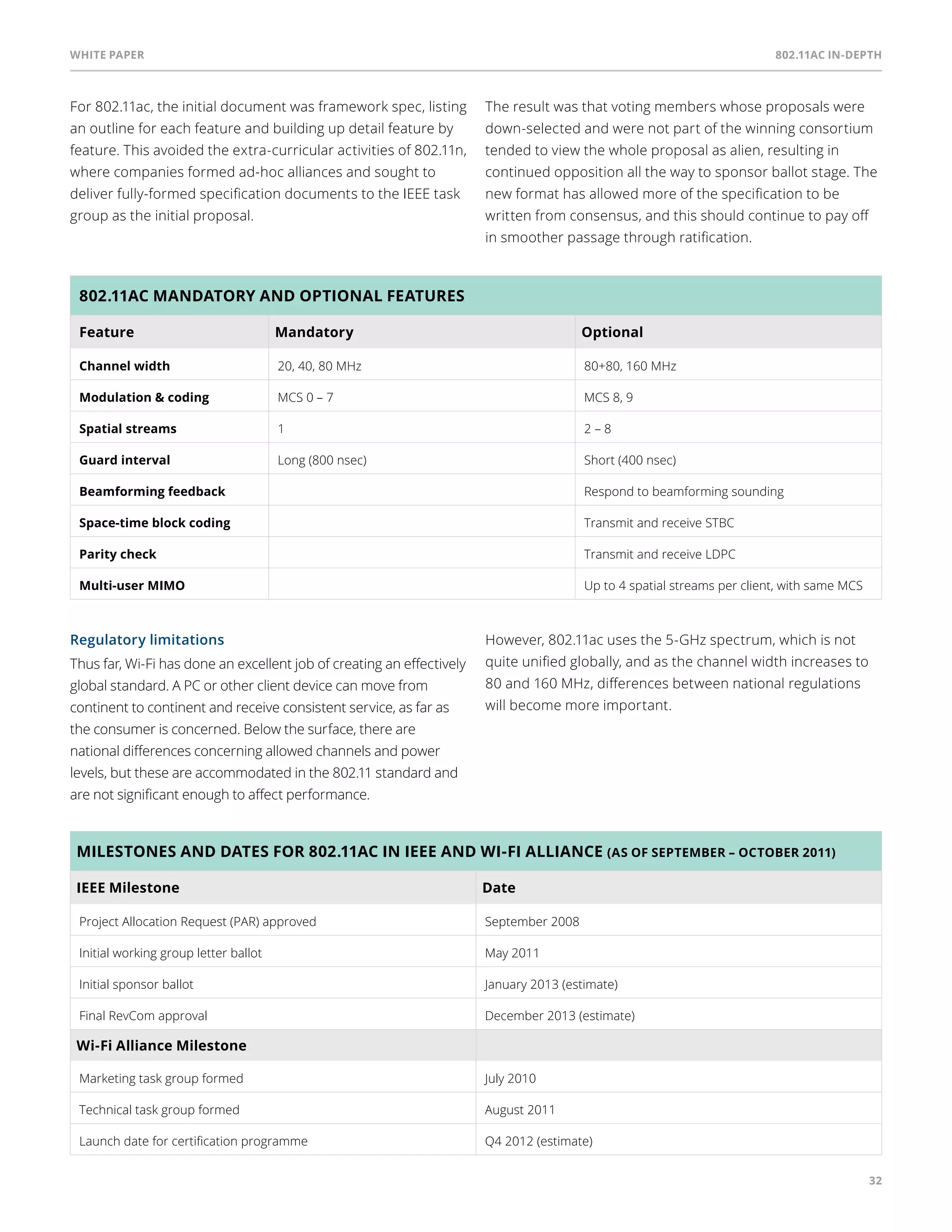

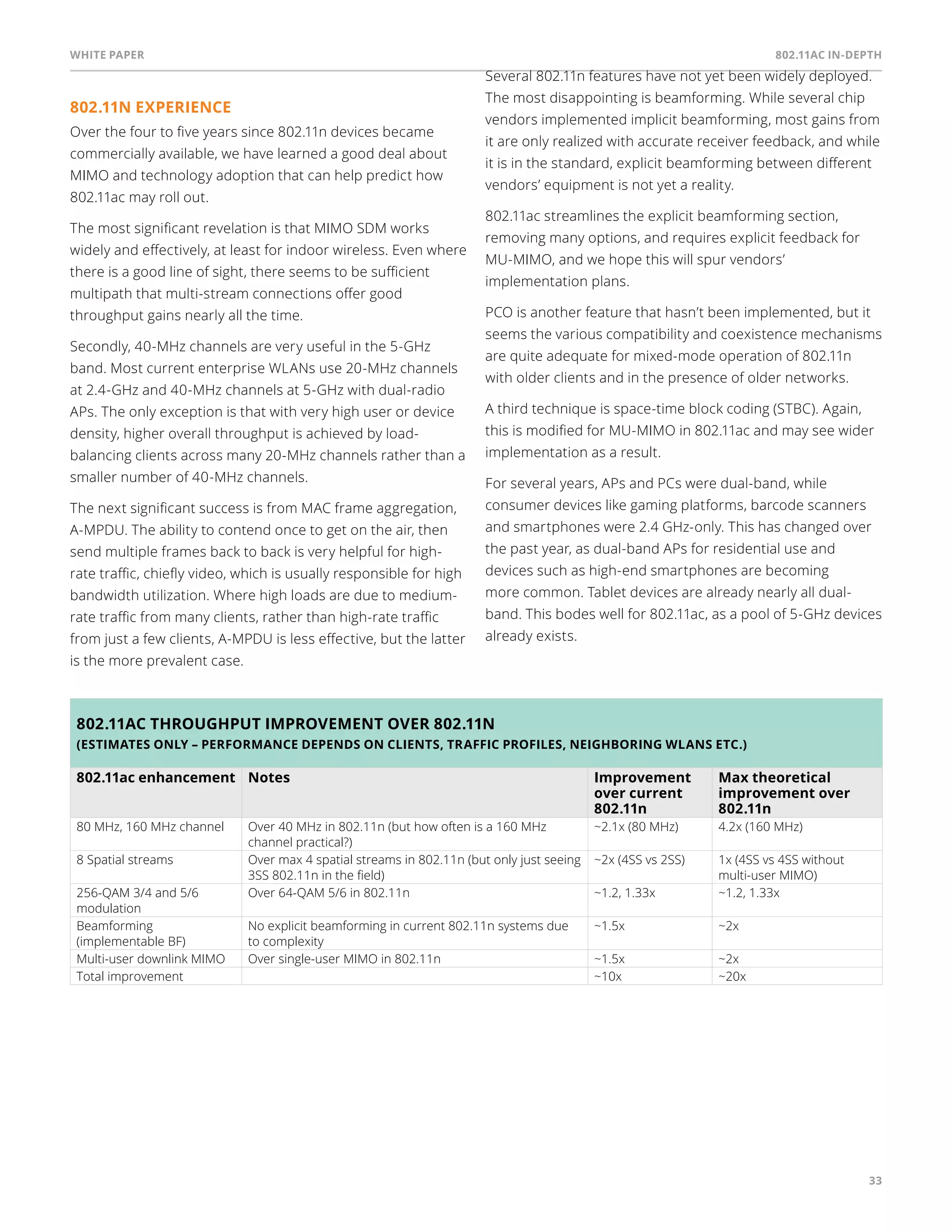

This document provides an overview and introduction to 802.11ac, the successor to 802.11n Wi-Fi. It discusses how 802.11ac aims to achieve throughput of 1 Gbps for multi-station and 500 Mbps for single links using enhancements to the physical layer including wider channels, more antennas, spatial streams, and new techniques like multi-user MIMO. The document also outlines several usage models for 802.11ac like wireless display and distribution of high-definition video as drivers for the higher speeds it provides.