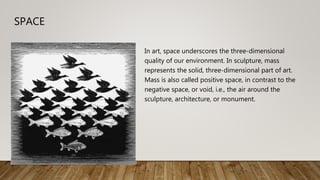

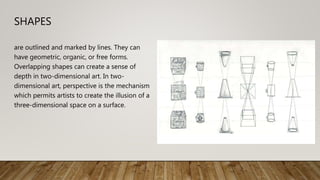

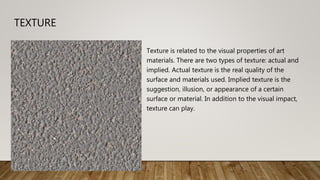

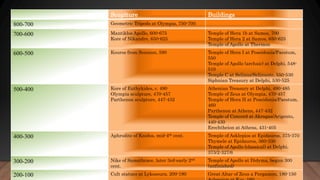

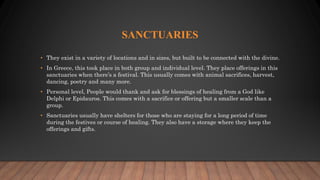

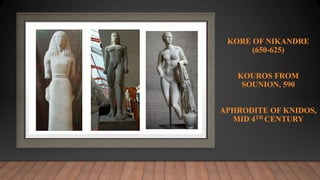

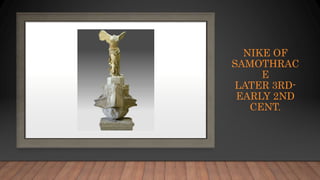

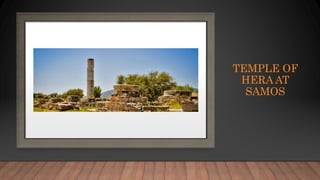

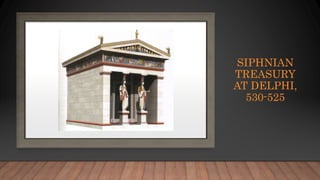

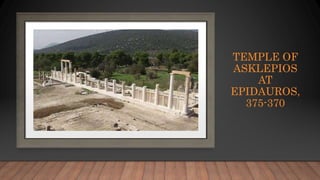

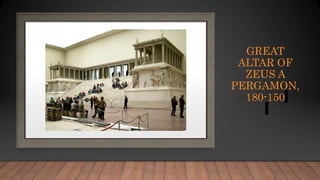

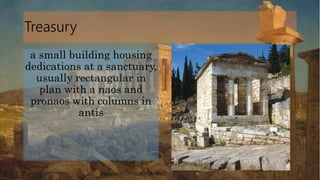

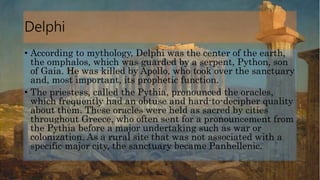

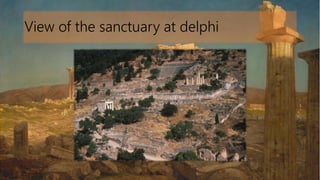

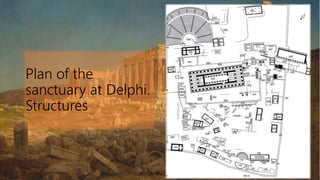

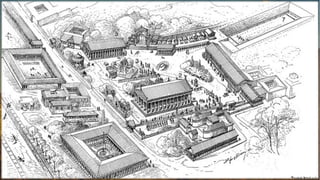

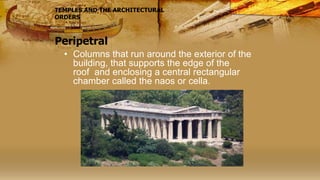

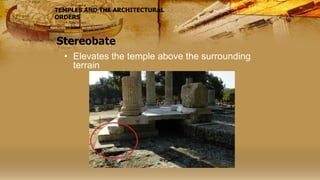

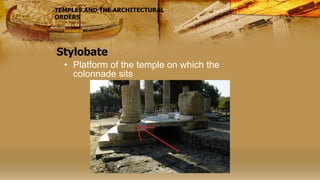

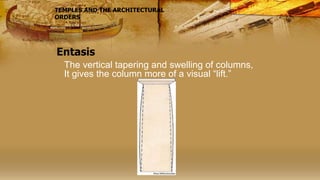

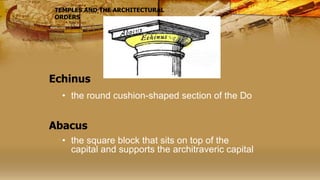

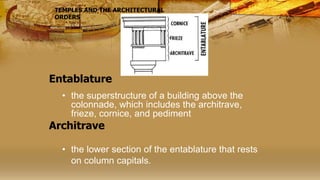

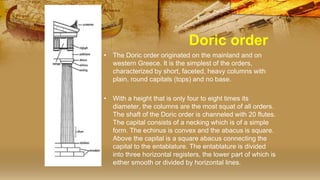

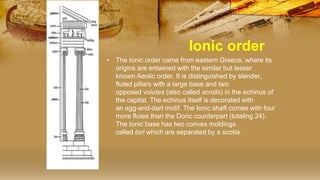

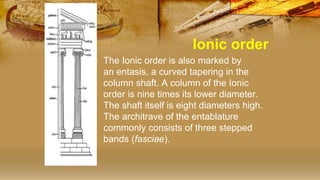

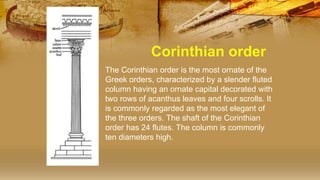

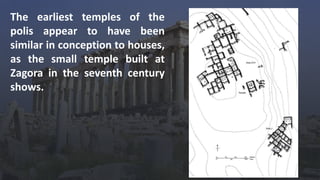

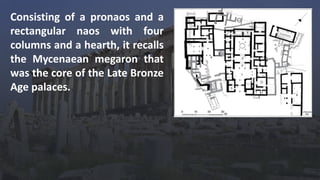

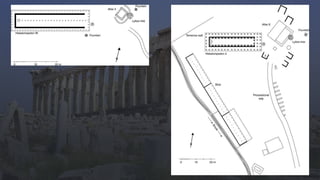

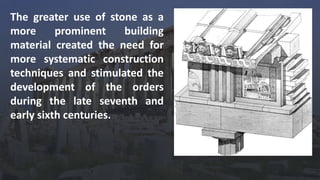

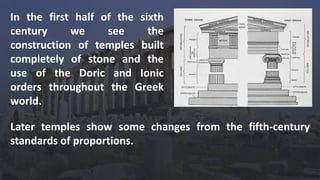

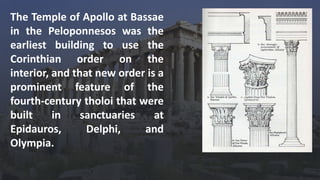

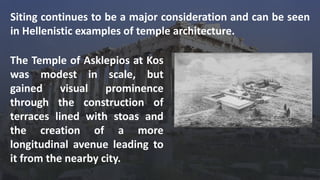

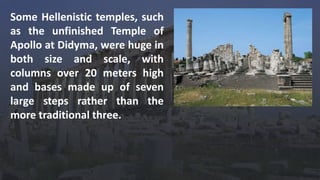

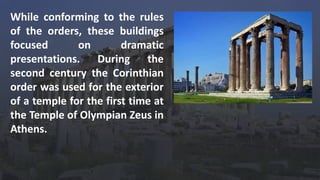

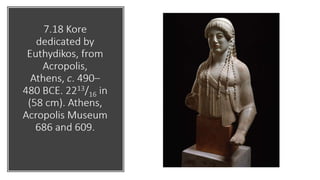

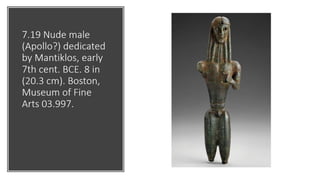

Group 5 presented on form and content in art as well as the basic elements of design such as line, color, space, shapes, light, texture, pattern, and time/motion. They discussed important Greek sculptures from 650-325 BCE like the Kore of Nikandre and Kouros from Sounion as well as buildings such as the Temple of Hera at Samos and Siphnian Treasury at Delphi. The presentation also covered sanctuaries and the architectural aspects of temples, highlighting the three Greek architectural orders of Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian and providing a mini-history of the evolution of the Greek temple from the 7th century BCE to 2nd century BCE.