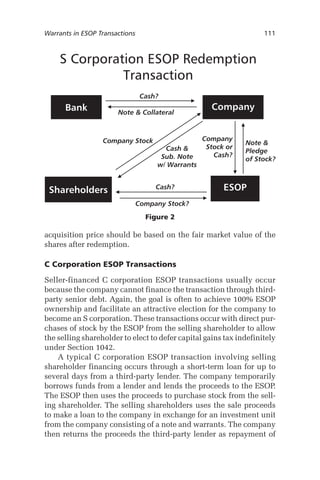

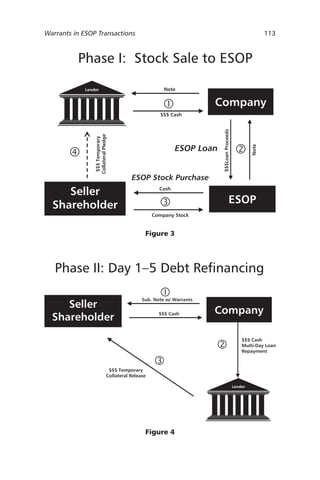

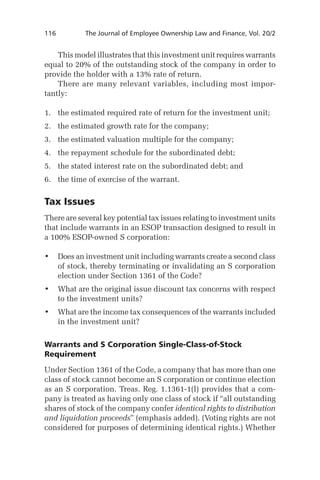

The document discusses the role of warrants in financing leveraged Employee Stock Ownership Plan (ESOP) transactions, including corporate finance and tax implications. It explains how warrants enhance returns for investors and debt holders and outlines their integration into both S and C corporation ESOP transactions. Additionally, the document provides methods for determining the appropriate number of warrants based on future company valuations and expected returns.