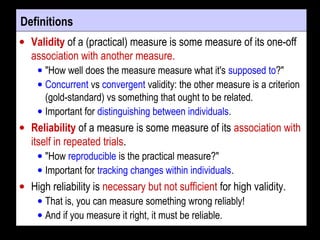

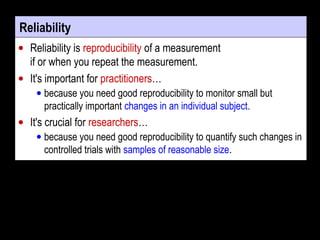

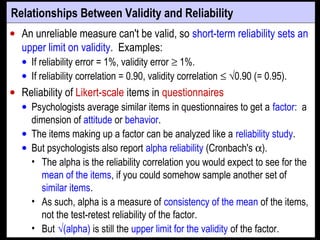

- Reliability is a measure of reproducibility of a test when repeated, quantifying random error. Validity is how well a test measures what it intends to, requiring comparison to a criterion.

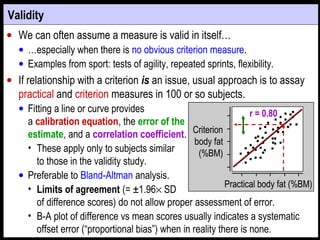

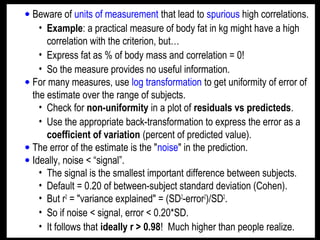

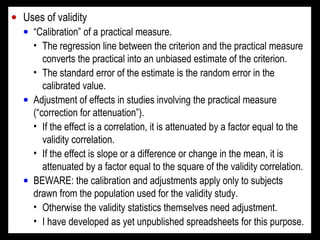

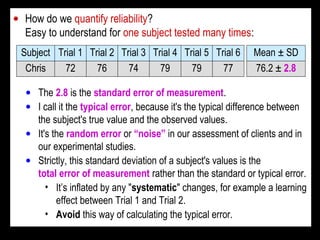

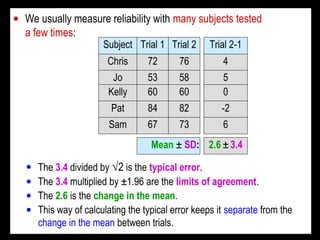

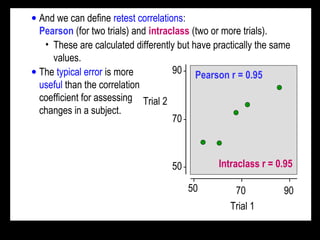

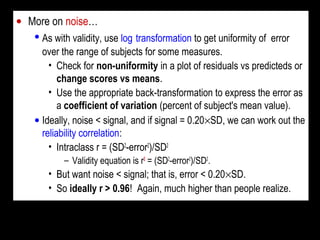

- Reliability is typically quantified by the typical error or intraclass correlation. Validity uses correlation and error of estimate from regression of the test on a criterion.

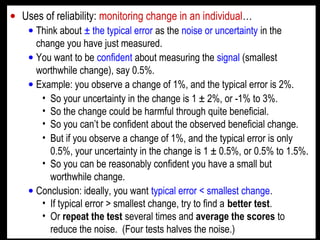

- Both reliability and validity should be high for a test to accurately track small individual changes over time and distinguish individuals. Ideal values are >0.96 for reliability and validity correlations and typical/estimate errors <20% of between-subject standard deviation.