This document provides practical tips for USAID managers on conducting participatory evaluations, emphasizing the active involvement of stakeholders throughout the evaluation process. Key characteristics include participant focus, ownership, flexible design, and reliance on empirical data. While participatory evaluations can improve program performance and commitment, they may also face challenges such as perceived bias and resource demands.

![7

Formats and page limits;

Requirements for datasets, if

primary data has been

collected;

A requirement to submit all

evaluations to the Development

Experience Clearing house for

archiving - this is the

responsibility of the evaluation

contractor; and

Other needs for

communicating, marketing and

disseminating results that are

the responsibility of the

evaluation team.

The SOW should specify when

working drafts are to be

submitted for review, the time

frame allowed for USAID review

and comment, and the time

frame to revise and submit the

final report.

11. INCLUDE A BUDGET

With the budget section, the

SOW comes full circle. As stated,

budget considerations have to be

part of the decision making

process from the beginning.

The budget is a product of the

questions asked, human

resources needed, logistical and

administrative support required,

and the time needed to produce

a high quality, rigorous and

useful evaluation report in the

most efficient and timely manner.

It is essential for contractors to

understand the quality, validity

and rigor required so they can

develop a responsive budget that

will meet the standards set forth

in the SOW.

For more information:

TIPS publications are available online at [insert website].

Acknowledgements:

Our thanks to those whose experience and insights helped shape this publication including USAID‟s

Office of Management Policy, Budget and Performance (MPBP). This publication was written by Richard

Blue, Ph.D. of Management Systems International.

Comments regarding this publication can be directed to:

Gerald Britan, Ph.D.

Tel: (202) 712-1158

gbritan@usaid.gov

Contracted under RAN-M-00-04-00049-A-FY0S-84

Integrated Managing for Results II](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/usaid-tipsseries-150106045150-conversion-gate02/85/Usaid-tips-series-18-320.jpg)

![References Cited

M. Bamberger, J. Rugh, and L. Mabry, Real World Evaluation. Working Under Budget, Time, Data, and Political

Constraints. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA, 2006.

T. Greenbaum, Moderating Focus Groups: A Practical Guide for Group Facilitation. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks,

CA, 2000.

K. Kumar, “Conducting Mini Surveys in Developing Countries,” USAID Program Design and Evaluation Methodology

Report No. 15, 1990 (revised 2006).

K. Kumar, “Conducting Group Interviews in Developing Countries,” USAID Program Design and Evaluation

Methodology Report No. 8, 1987.

K. Kumar, “Conducting Key Informant Interviews in Developing Countries,” USAID Program Design and Evaluation

Methodology Report No. 13, 1989.

For more information:

TIPS publications are available online at [insert website].

Acknowledgements:

Our thanks to those whose experience and insights helped shape this publication including USAID’s Office of

Management Policy, Budget and Performance (MPBP). This publication was authored by Patricia Vondal, PhD., of

Management Systems International.

Comments regarding this publication can be directed to:

Gerald Britan, Ph.D.

Tel: (202) 712-1158

gbritan@usaid.gov

Contracted under RAN-M-00-04-00049-A-FY0S-84

Integrated Managing for Results II

6](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/usaid-tipsseries-150106045150-conversion-gate02/85/Usaid-tips-series-28-320.jpg)

![12

For more information:

TIPS publications are available online at [insert website].

Acknowledgements:

Our thanks to those whose experience and insights helped shape this publication, including Gerry Britan

and Subhi Mehdi of USAID’s Office of Management Policy, Budget and Performance (MPBP). This

publication was updated by Michelle Adams-Matson of Management Systems International.

Comments can be directed to:

Gerald Britan, Ph.D.

Tel: (202) 712-1158

gbritan@usaid.gov

Contracted under RAN-M-00-04-00049-A-FY0S-84

Integrated Managing for Results II](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/usaid-tipsseries-150106045150-conversion-gate02/85/Usaid-tips-series-40-320.jpg)

![For more information:

TIPS publications are available online at [insert website].

Acknowledgements:

Our thanks to those whose experience and insights helped shape this publication, including Gerry Britan and

Subhi Mehdi of USAID’s Office of Management Policy, Budget and Performance (MPBP). This publication was

updated by Jill Tirnauer of Management Systems International.

Comments can be directed to:

Gerald Britan, Ph.D.

Tel: (202) 712-1158

gbritan@usaid.gov

Contracted under RAN-M-00-04-00049-A-FY0S-84

Integrated Managing for Results II

7](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/usaid-tipsseries-150106045150-conversion-gate02/85/Usaid-tips-series-51-320.jpg)

![8

resources were to be

expended. Sometimes

preliminary estimates may be

obtainable, but they should be

clearly flagged as such and

replaced as soon as possible

as the final data become

available from the source.

The following example

demonstrates issues related to

timeliness:

Result: Primary school

attrition in a targeted

region reduced.

Indicator: Rate of

student attrition at

targeted schools.

In August 2009, the Ministry

of Education published full

enrollment analysis for the

2007 school year.

In this case, currency is a

problem because there is a 2

year time lag for these data.

While it is optimal to collect

and report data based on the

U.S. Government fiscal year,

there are often a number of

practical challenges in doing

so. We recognize that data

may come from preceding

calendar or fiscal years.

Moreover, data often measure

results for the specific point in

time that the data were

collected, not from September

to September, or December to

December.

Often the realities of the

recipient country context will

dictate the appropriate timing

of the data collection effort,

rather than the U.S. fiscal year.

For example, if agricultural

yields are at their peak in July,

then data collection efforts to

measure yields should be

conducted in July of each

year. Moreover, to the extent

that USAID relies on

secondary data sources and

partners for data collection,

we may not be able to dictate

exact timing

ASSESSING DATA

QUALITY

Approaches and steps for how

to assess data quality are

discussed in more detail in

TIPS 18: Conducting Data

Quality Assessments. USAID

policy requires managers to

understand the strengths and

weaknesses of the data they

use on an on-going basis. In

addition, a Data Quality

Assessment (DQA) must be

conducted at least once every

3 years for those data

reported to Washington (ADS

203.3.5.2).

For more information:

TIPS publications are available online at [insert website]

Acknowledgements:

Our thanks to those whose experience and insights helped shape this publication including Gerry Britan

and Subhi Mehdi of USAID’s Office of Management Policy, Budget and Performance (MPBP). This

publication was updated by Michelle Adams-Matson of Management Systems International (MSI).

Comments regarding this publication can be directed to:

Gerald Britan, Ph.D.

Tel: (202) 712-1158

gbritan@usaid.gov

Contracted under RAN-M-00-04-00049-A-FY0S-84

Integrated Managing for Results II](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/usaid-tipsseries-150106045150-conversion-gate02/85/Usaid-tips-series-71-320.jpg)

![12

For more information:

TIPS publications are available online at [insert website].

Acknowledgements:

Our thanks to those whose experience and insights helped shape this publication including Gerry Britan

and Subhi Mehdi of USAID’s Office of Management Policy, Budget and Performance (MPBP). This

publication was updated by Michelle Adams-Matson, of Management Systems International.

Comments can be directed to:

Gerald Britan, Ph.D.

Tel: (202) 712-1158

gbritan@usaid.gov

Contracted under RAN-M-00-04-00049-A-FY0S-84

Integrated Managing for Results II](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/usaid-tipsseries-150106045150-conversion-gate02/85/Usaid-tips-series-83-320.jpg)

![2

Mabry [2006] for further

explanation and descriptions of

triangulation strategies used in

evaluations.)

When reliance on one method

alone may not be sufficient to

answer all aspects of each

evaluation question.

When the data collected from

one method can help interpret

findings from the analysis of

data collected from another

method. For example,

qualitative data from in-depth

interviews or focus groups can

help interpret statistical

patterns from quantitative data

collected through a random-

sample survey. This yields a

richer analysis and can also

provide a better understanding

of the context in which a

program operates.

There are a number of additional

benefits derived from using a mix

of methods in any given

evaluation.

Using mixed-methods can

more readily yield examples of

unanticipated changes or

responses.

Mixed-method evaluations

have the potential of surfacing

other key issues and providing

a deeper understanding of

program context that should

be considered when analyzing

data and developing findings

and conclusions.

Mixed-method evaluations

often yield a wider range of

points of view that might

otherwise be missed.

DETERMINING

WHICH METHODS TO

USE

In a mixed-method evaluation,

the evaluator may use a

combination of methods, such as

a survey using comparison

groups in a quasi-experimental or

experimental design, a review of

key documents, a reanalysis of

government statistics, in-depth

interviews with key informants,

focus groups, and structured

observations. The selection of

methods, or mix, depends on the

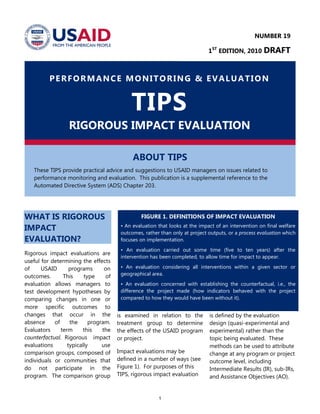

Key Steps in Developing a Mixed-Method Evaluation Design and Analysis

Strategy

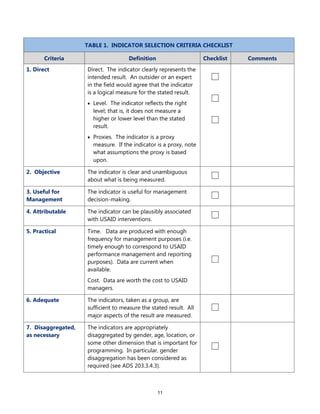

1. In order to determine the methods that will be employed, carefully review the purpose of the evaluation and the

primary evaluation questions. Then select the methods that will be the most useful and cost-effective to answer

each question in the time period allotted for the evaluation. Sometimes it is apparent that there is one method

that can be used to answer most, but not all, aspects of the evaluation question.

2. Select complementary methods to cover different aspects of the evaluation question (for example, the how and

why issues) that the first method selected cannot alone answer, and/or to enrich and strengthen data analysis

and interpretation of findings.

3. In situations when the strength of findings and conclusions for a key question is absolutely essential, employ a

triangulation strategy. What additional data sources and methods can be used to obtain information to answer

the same question in order to increase the validity of findings from the first method selected?

4. Re-examine the purpose of the evaluation and the methods initially selected to ensure that all aspects of the

primary evaluation questions are covered thoroughly. This is the basis of the evaluation design. Develop data

collection instruments accordingly.

5. Design a data analysis strategy to analyze the data that will be generated from the selection of methods chosen

for the evaluation.

6. Ensure that the evaluation team composition includes members that are well-versed and experienced in applying

each type of data collection method and subsequent analysis.

7. Ensure that there is sufficient time in the evaluation statement of work for evaluators to fully analyze data

generated from each method employed and to realize the benefits of conducting a mixed method evaluation.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/usaid-tipsseries-150106045150-conversion-gate02/85/Usaid-tips-series-114-320.jpg)

![9

For more information:

TIPS publications are available online at [insert website].

Acknowledgements:

Our thanks to those whose experience and insights helped shape this publication including USAID’s

Office of Management Policy, Budget and Performance (MPBP). This publication was written by Dr.

Patricia Vondal of Management Systems International.

Comments regarding this publication can be directed to:

Gerald Britan, Ph.D.

Tel: (202) 712-1158

gbritan@usaid.gov

Contracted under RAN-M-00-04-00049-A-FY0S-84

Integrated Managing for Results II](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/usaid-tipsseries-150106045150-conversion-gate02/85/Usaid-tips-series-121-320.jpg)

![11

For more information:

TIPS publications are available online at [insert website].

Acknowledgements:

Our thanks to those whose experience and insights helped shape this publication including Gerry Britan and

Subhi Mehdi of USAID’s Office of Management Policy, Budget and Performance (MPBP). This publication was

written by Larry Beyna of Management Systems International (MSI).

Comments regarding this publication can be directed to:

Gerald Britan, Ph.D.

Tel: (202) 712-1158

gbritan@usaid.gov

Contracted under RAN-M-00-04-00049-A-FY0S-84

Integrated Managing for Results II](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/usaid-tipsseries-150106045150-conversion-gate02/85/Usaid-tips-series-132-320.jpg)

![9

For more information:

TIPS publications are available online at [insert website].

Acknowledgements:

Our thanks to those whose experience and insights helped shape this publication including Gerry Britan and

Subhi Mehdi of USAID’s Office of Management Policy, Budget and Performance (MPBP). This publication was

written by Michelle Adams-Matson, of Management Systems International.

Comments can be directed to:

Gerald Britan, Ph.D.

Tel: (202) 712-1158

gbritan@usaid.gov

Contracted under RAN-M-00-04-00049-A-FY0S-84

Integrated Managing for Results II](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/usaid-tipsseries-150106045150-conversion-gate02/85/Usaid-tips-series-141-320.jpg)

![11

For more information:

TIPS publications are available online at [insert website]

Acknowledgements:

Our thanks to those whose experience and insights helped shape this publication including USAID’s

Office of Management Policy, Budget and Performance (MPBP). This publication was written by Michael

Duthie of Management Systems International.

Comments regarding this publication can be directed to:

Gerald Britan, Ph.D.

Tel: (202) 712-1158

gbritan@usaid.gov

Contracted under RAN-M-00-04-00049-A-FY0S-84

Integrated Managing for Results II](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/usaid-tipsseries-150106045150-conversion-gate02/85/Usaid-tips-series-152-320.jpg)