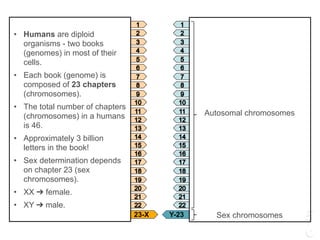

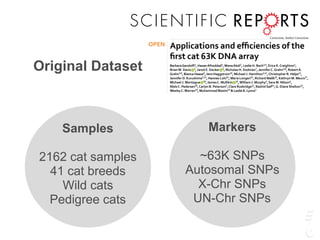

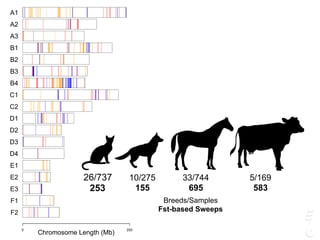

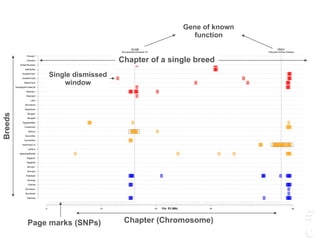

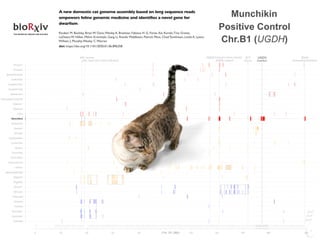

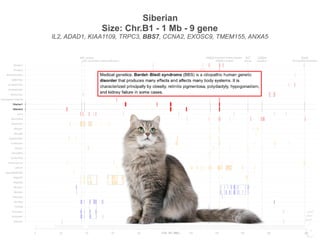

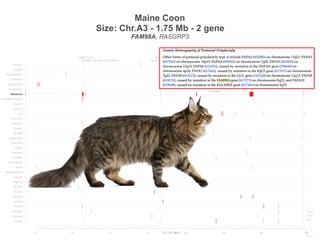

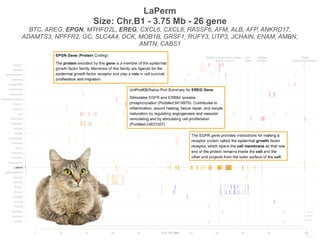

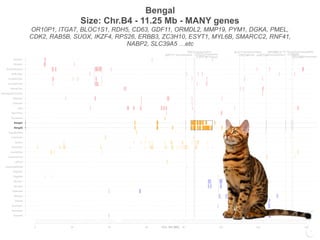

The document discusses a webinar focusing on the genomic potential of domestic cats, highlighting candidate regions under selection and the importance of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) for disease and phenotype association discovery. It emphasizes the need for a comprehensive SNP map to facilitate research into hereditary diseases and traits across various cat breeds. The findings aim to enhance understanding of genetic determinants and assist in developing genotyping platforms for feline health management.

![Mullikin et al. BMC Genomics 2010, 11:406

http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2164/11/406

Open AccessDATABASE

Database

Light whole genome sequence for SNP discovery

across domestic cat breeds

James C Mullikin*1, Nancy F Hansen1, Lei Shen2, Heather Ebling2, William F Donahue2, Wei Tao2, David J Saranga2,

Adrianne Brand2, Marc J Rubenfield2, Alice C Young1, Pedro Cruz1 for NISC Comparative Sequencing Program1,

Carlos Driscoll3, Victor David3, Samer WK Al-Murrani4, Mary F Locniskar4, Mitchell S Abrahamsen4, Stephen J O'Brien3,

Douglas R Smith2 and Jeffrey A Brockman4

Abstract

Background: The domestic cat has offered enormous genomic potential in the veterinary description of over 250

hereditary disease models as well as the occurrence of several deadly feline viruses (feline leukemia virus -- FeLV, feline

coronavirus -- FECV, feline immunodeficiency virus - FIV) that are homologues to human scourges (cancer, SARS, and

AIDS respectively). However, to realize this bio-medical potential, a high density single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP)

map is required in order to accomplish disease and phenotype association discovery.

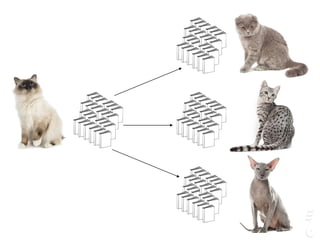

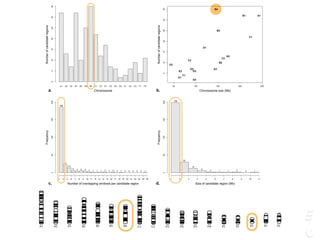

Description: To remedy this, we generated 3,178,297 paired fosmid-end Sanger sequence reads from seven cats, and

combined these data with the publicly available 2X cat whole genome sequence. All sequence reads were assembled

together to form a 3X whole genome assembly allowing the discovery of over three million SNPs. To reduce potential

false positive SNPs due to the low coverage assembly, a low upper-limit was placed on sequence coverage and a high

lower-limit on the quality of the discrepant bases at a potential variant site. In all domestic cats of different breeds:

female Abyssinian, female American shorthair, male Cornish Rex, female European Burmese, female Persian, female

Siamese, a male Ragdoll and a female African wildcat were sequenced lightly. We report a total of 964 k common SNPs

suitable for a domestic cat SNP genotyping array and an additional 900 k SNPs detected between African wildcat and

domestic cats breeds. An empirical sampling of 94 discovered SNPs were tested in the sequenced cats resulting in a

SNP validation rate of 99%.

Conclusions: These data provide a large collection of mapped feline SNPs across the cat genome that will allow for the

development of SNP genotyping platforms for mapping feline diseases.

Background

Along with dogs, the domestic cat enjoys extensive veter-

inary surveillance, more than any other animal. A rich lit-

erature of feline veterinary models reveals a unique

opportunity to explore genetic determinants responsible

ion to people since their original domestication from the

Asian wildcat (Felis silvestris lybica), recently estimated at

approximately 10,000 years ago in the Middle East's Fer-

tile Crescent[3]. In spite of our affection for cats,

advances in clinical resolution of genetic maladies and

10.1101/gr.6380007Access the most recent version at doi:

2007 17: 1675-1689Genome Res.

Bourque, Glenn Tesler, NISC Comparative Sequencing Program and Stephen J. O’Brien

Antunes, Marilyn Menotti-Raymond, Naoya Yuhki, Jill Pecon-Slattery, Warren E. Johnson, Guillaume

A. Schäffer, Richa Agarwala, Kristina Narfström, William J. Murphy, Urs Giger, Alfred L. Roca, Agostinho

Sante Gnerre, Michele Clamp, Jean Chang, Robert Stephens, Beena Neelam, Natalia Volfovsky, Alejandro

Joan U. Pontius, James C. Mullikin, Douglas R. Smith, Agencourt Sequencing Team, Kerstin Lindblad-Toh,

Initial sequence and comparative analysis of the cat genome

data

Supplementary

http://www.genome.org/cgi/content/full/17/11/1675/DC1

"Supplemental Research Data"

References

http://www.genome.org/cgi/content/full/17/11/1675#References

This article cites 97 articles, 41 of which can be accessed free at:

service

Email alerting

click heretop right corner of the article or

Receive free email alerts when new articles cite this article - sign up in the box at the

Notes

http://www.genome.org/subscriptions/

go to:Genome ResearchTo subscribe to

© 2007 Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press

Comparative analysis of the domestic cat genome

reveals genetic signatures underlying feline

biology and domestication

Michael J. Montaguea,1

, Gang Lib,1

, Barbara Gandolfic

, Razib Khand

, Bronwen L. Akene

, Steven M. J. Searlee

,

Patrick Minxa

, LaDeana W. Hilliera

, Daniel C. Koboldta

, Brian W. Davisb

, Carlos A. Driscollf

, Christina S. Barrf

,

Kevin Blackistonef

, Javier Quilezg

, Belen Lorente-Galdosg

, Tomas Marques-Bonetg,h

, Can Alkani

, Gregg W. C. Thomasj

,

Matthew W. Hahnj

, Marilyn Menotti-Raymondk

, Stephen J. O’Brienl,m

, Richard K. Wilsona

, Leslie A. Lyonsc,2

,

William J. Murphyb,2

, and Wesley C. Warrena,2

a

The Genome Institute, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO 63108; b

Department of Veterinary Integrative Biosciences, College of

Veterinary Medicine, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX 77843; c

Department of Veterinary Medicine & Surgery, College of Veterinary Medicine,

University of Missouri, Columbia, MO 65201; d

Population Health & Reproduction, School of Veterinary Medicine, University of California, Davis, CA 95616;

e

Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, Hinxton CB10 1SA, United Kingdom; f

National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, National Institutes of Health,

Bethesda, MD 20886; g

Catalan Institution for Research and Advanced Studies, Institute of Evolutionary Biology, Pompeu Fabra University, 08003

Barcelona, Spain; h

Centro de Analisis Genomico 08028, Barcelona, Spain; i

Department of Computer Engineering, Bilkent University, Ankara 06800, Turkey;

j

Department of Biology, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN 47405; k

Laboratory of Genomic Diversity, Center for Cancer Research, Frederick, MD 21702;

l

Dobzhansky Center for Genome Bioinformatics, St. Petersburg State University, St. Petersburg 199178, Russia; and m

Oceanographic Center, Nova

Southeastern University, Fort Lauderdale, FL 33314

Edited by James E. Womack, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX, and approved October 3, 2014 (received for review June 2, 2014)

Little is known about the genetic changes that distinguish

domestic cat populations from their wild progenitors. Here we

describe a high-quality domestic cat reference genome assembly

and comparative inferences made with other cat breeds, wildcats,

and other mammals. Based upon these comparisons, we identified

positively selected genes enriched for genes involved in lipid

Previous studies have assessed breed differentiation (6, 7),

phylogenetic origins of the domestic cat (8), and the extent of

recent introgression between domestic cats and wildcats (9, 10).

However, little is known regarding the impact of the domesti-

cation process within the genomes of modern cats and how this

compares with genetic changes accompanying selection identified in

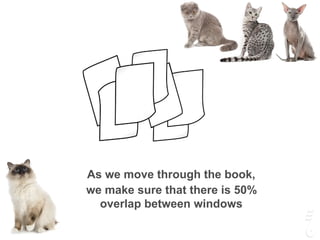

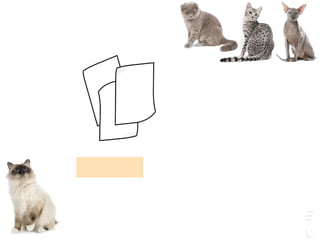

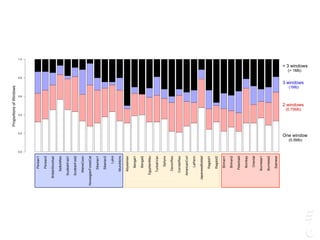

GENETICS](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/hasanwinn2020-201207114157/85/Unique-pages-in-the-cat-s-book-10-320.jpg)

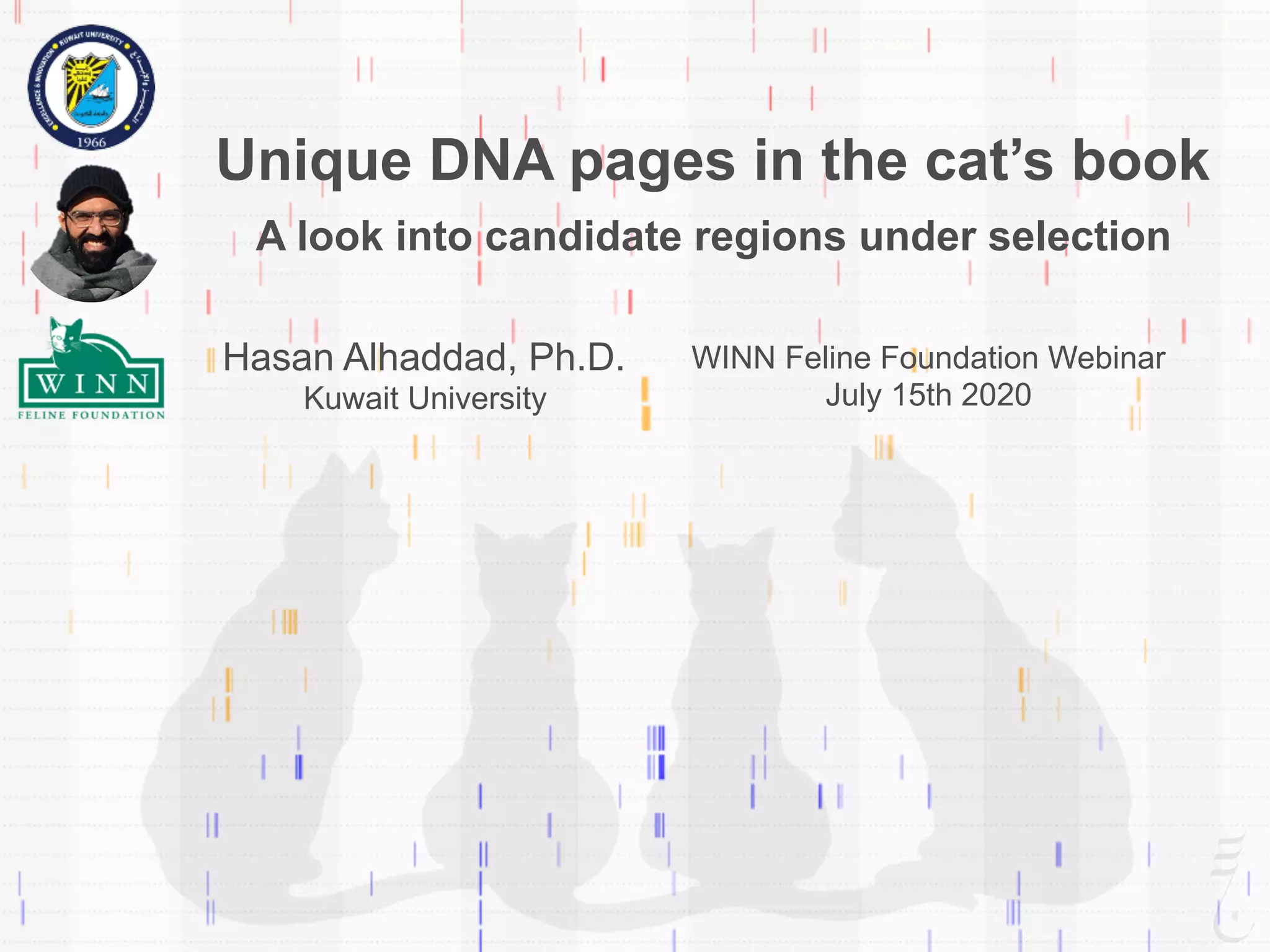

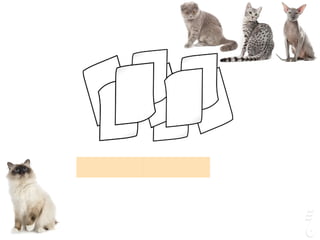

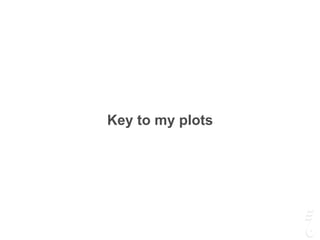

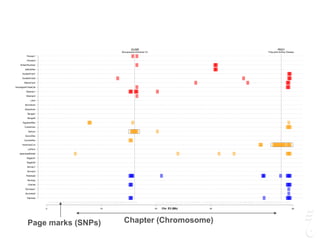

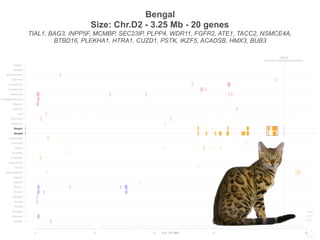

![LPAR6 Rexing

HEXB Gangliosidosis 2

ARSB Mucopolysaccharidosis VI

FXII Factor XII DeficiencyATP7B Copper Metabolism LVRN Tabby

0 20 40 60 80 100 140 160 180 200 220 243

Siamese

Burmese2

Burmese1

Oriental

Bombay

Peterbald

Birman2

Birman1

Ragdoll2

Ragdoll1

JapaneseBobtail

LaPerm

AmericanCurl

CornishRex

DevonRex

Sphynx

TurkishVan

EgyptianMau

Bengal2

Bengal1

Abyssinian

Munchkins

Lykoi

Siberian2

Siberian1

NorwegianForestCat

MaineCoon

ScottishFold2

ScottishFold1

SelkirkRex

BritishShorthair

Persian2

Persian1

Chr. A1 (Mb)

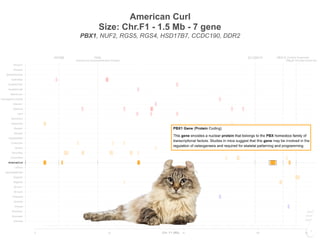

To the Root of the Curl: A Signature of a Recent Selective

Sweep Identifies a Mutation That Defines the Cornish

Rex Cat Breed

Barbara Gandolfi1

*, Hasan Alhaddad1

, Verena K. Affolter2

, Jeffrey Brockman3

, Jens Haggstrom4

,

Shannon E. K. Joslin1

, Amanda L. Koehne2

, James C. Mullikin5

, Catherine A. Outerbridge6

,

Wesley C. Warren7

, Leslie A. Lyons1

1 Department of Population Health and Reproduction, School of Veterinary Medicine, University of California - Davis, Davis, California, United States of America,

2 Department of Pathology, Microbiology, Immunology, School of Veterinary Medicine, University of California - Davis, Davis, California, United States of America, 3 Hill’s

Pet Nutrition Center, Topeka, Kansas, United States of America, 4 Department of Clinical Sciences, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine and Animal Science, Swedish University

of Agricultural Sciences, Uppsala, Sweden, 5 Comparative Genomics Unit, Genome Technology Branch, National Human Genome Research Institute, National Institutes of

Health, Bethesda, Maryland, United States of America, 6 Department of Veterinary Medicine & Epidemiology, School of Veterinary Medicine, University of California - Davis,

Davis, California, United States of America, 7 The Genome Institute, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri, United States of America

Abstract

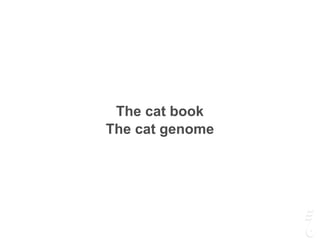

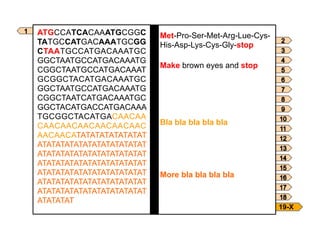

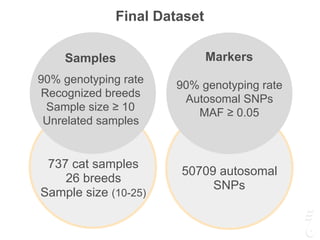

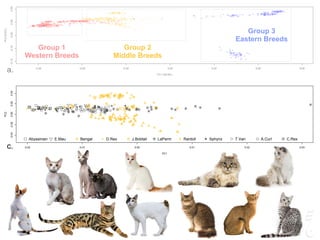

The cat (Felis silvestris catus) shows significant variation in pelage, morphological, and behavioral phenotypes amongst its

over 40 domesticated breeds. The majority of the breed specific phenotypic presentations originated through artificial

selection, especially on desired novel phenotypic characteristics that arose only a few hundred years ago. Variations in coat

texture and color of hair often delineate breeds amongst domestic animals. Although the genetic basis of several feline coat

colors and hair lengths are characterized, less is known about the genes influencing variation in coat growth and texture,

especially rexoid – curly coated types. Cornish Rex is a cat breed defined by a fixed recessive curly coat trait. Genome-wide

analyses for selection (di, Tajima’s D and nucleotide diversity) were performed in the Cornish Rex breed and in 11

phenotypically diverse breeds and two random bred populations. Approximately 63K SNPs were used in the analysis that

aimed to localize the locus controlling the rexoid hair texture. A region with a strong signature of recent selective sweep

was identified in the Cornish Rex breed on chromosome A1, as well as a consensus block of homozygosity that spans

approximately 3 Mb. Inspection of the region for candidate genes led to the identification of the lysophosphatidic acid

receptor 6 (LPAR6). A 4 bp deletion in exon 5, c.250_253_delTTTG, which induces a premature stop codon in the receptor,

was identified via Sanger sequencing. The mutation is fixed in Cornish Rex, absent in all straight haired cats analyzed, and is

also segregating in the German Rex breed. LPAR6 encodes a G protein-coupled receptor essential for maintaining the

structural integrity of the hair shaft; and has mutations resulting in a wooly hair phenotype in humans.

Citation: Gandolfi B, Alhaddad H, Affolter VK, Brockman J, Haggstrom J, et al. (2013) To the Root of the Curl: A Signature of a Recent Selective Sweep Identifies a

Mutation That Defines the Cornish Rex Cat Breed. PLoS ONE 8(6): e67105. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0067105

Editor: Arnar Palsson, University of Iceland, Iceland

Received March 26, 2013; Accepted May 14, 2013; Published June 27, 2013

Copyright: ß 2013 Gandolfi et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits

unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Funding: This project was supported by the National Center for Research Resources and the Office of Research Infrastructure Programs of the National Institute

of Health through Grant Number R24 RR016094, the Winn Feline Foundation (W10-14, W11-041), the Center for Companion Animal Health at University of

California Davis (2010-09-F) (http://www.vetmed.ucdavis.edu/ccah/index.cfm), and the George and Phyllis Miller Feline Health Fund of the San Francisco

Foundation (2008-36-F). Support for the development of the Illumina Infinium Feline 63K iSelect DNA array was provided by the Morris Animal Foundation (http://

www.morrisanimalfoundation.org) via a donation from Hill’s Pet Food, Inc. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to

publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing Interests: JB works for a private company (Hill’s Pet Food, Inc) that partially sponsored the development of the 63k feline SNP array. The funder had

no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

* E-mail: bgandolfi@ucdavis.edu

Introduction

Phenotypic traits under strong artificial selection within cat

breeds vary from body types, muzzle shape, tail length to

aesthetically pleasant traits, such as hair color, length and texture.

Hair represents one of the defining characteristic of mammals.

Hair provides body temperature regulation, protection from

environmental elements, and adaptive advantages of camouflage,

as well as often having aesthetic value to humans. The hair follicle

has a highly complex structure with eight distinct cell layers, in

which hundreds of gene products play a key role in the hair cycle

maintenance [1,2]. In the past decade, numerous genes expressed

in the hair follicle have been identified and mutations in some of

these genes have been shown to underlie hereditary hair diseases

in humans and other mammals [3]. Hereditary hair diseases in

mammals show diverse hair phenotypes, such as sparse or short

hairs (hypotrichosis), excessive or elongated hairs (hypertrichosis),

and hair shaft anomalies, creating rexoid/woolly hairs [3–12].

Causative genes for the diseases encode various proteins with

different functions, such as structural proteins, transcription

factors, and signaling molecules. Mutations within structural

proteins, such as epithelial and hair keratins, are often associated

with hair disease. To date, mutations in several hair keratin genes

underlined two hereditary hair disorders: monilethrix, character-

PLOS ONE | www.plosone.org 1 June 2013 | Volume 8 | Issue 6 | e67105

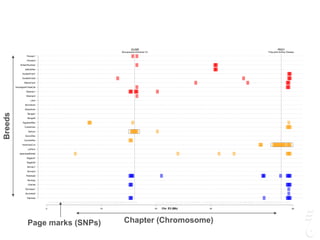

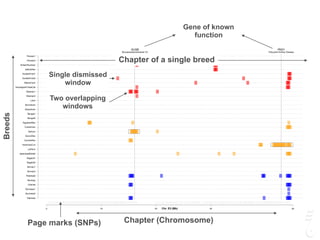

Cornish Rex

Positive Control

Chr.A1 (LPAR6)

LPAR6 Rexing

HEXB Gangliosidosis 2

ARSB Mucopolysaccharidosis VI

FXII Factor XII DeficiencyATP7B Copper Metabolism LVRN Tabby

0 20 40 60 80 100 140 160 180 200 220 243

Siamese

Burmese2

Burmese1

Oriental

Bombay

Peterbald

Birman2

Birman1

Ragdoll2

Ragdoll1

JapaneseBobtail

LaPerm

AmericanCurl

CornishRex

DevonRex

Sphynx

TurkishVan

EgyptianMau

Bengal2

Bengal1

Abyssinian

Munchkins

Lykoi

Siberian2

Siberian1

NorwegianForestCat

MaineCoon

ScottishFold2

ScottishFold1

SelkirkRex

BritishShorthair

Persian2

Persian1

Chr. A1 (Mb)

LPAR6 Rexing

HEXB Gangliosidosis 2

ARSB Mucopolysaccharidosis VI

FXII Factor XII DeficiencyATP7B Copper Metabolism LVRN Tabby

0 20 40 60 80 100 140 160 180 200 220 243

Siamese

Burmese2

Burmese1

Oriental

Bombay

Peterbald

Birman2

Birman1

Ragdoll2

Ragdoll1

JapaneseBobtail

LaPerm

AmericanCurl

CornishRex

DevonRex

Sphynx

TurkishVan

EgyptianMau

Bengal2

Bengal1

Abyssinian

Munchkins

Lykoi

Siberian2

Siberian1

NorwegianForestCat

MaineCoon

ScottishFold2

ScottishFold1

SelkirkRex

BritishShorthair

Persian2

Persian1

Chr. A1 (Mb)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/hasanwinn2020-201207114157/85/Unique-pages-in-the-cat-s-book-72-320.jpg)

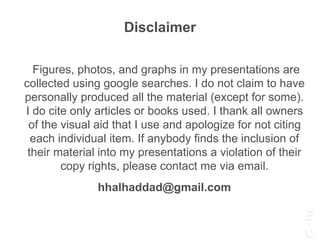

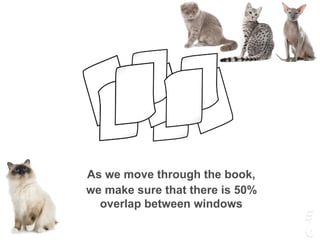

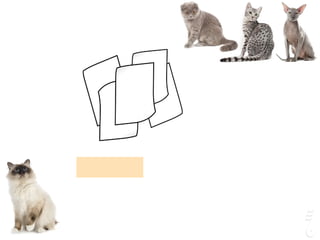

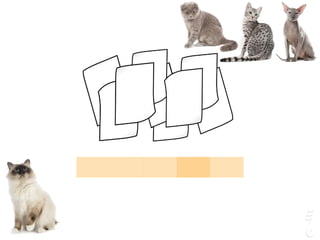

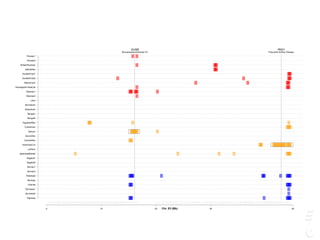

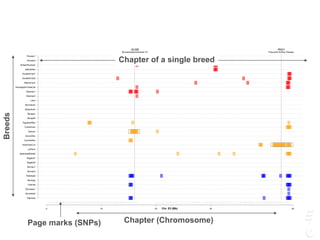

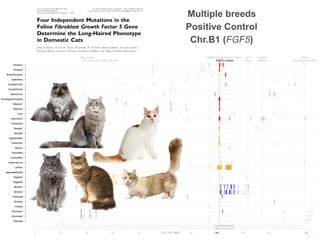

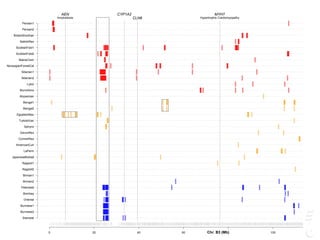

![FGF5 Longhair

KIT

Gloves

PKD2 Polycystic kidney disease UGDH

Dwarfism

HR Hairless IDUA

MucopolysaccharidosisLPL Lipoprotein Lipase Deficiency

0 20 40 60 80 120 140 160 180 209

Siamese

Burmese2

Burmese1

Oriental

Bombay

Peterbald

Birman2

Birman1

Ragdoll2

Ragdoll1

JapaneseBobtail

LaPerm

AmericanCurl

CornishRex

DevonRex

Sphynx

TurkishVan

EgyptianMau

Bengal2

Bengal1

Abyssinian

Munchkins

Lykoi

Siberian2

Siberian1

NorwegianForestCat

MaineCoon

ScottishFold2

ScottishFold1

SelkirkRex

BritishShorthair

Persian2

Persian1

Chr. B1 (Mb)

FGF5 Longhair

KIT

Gloves

PKD2 Polycystic kidney disease UGDH

Dwarfism

HR Hairless IDUA

MucopolysaccharidosisLPL Lipoprotein Lipase Deficiency

0 20 40 60 80 120 140 160 180 209

Siamese

Burmese2

Burmese1

Oriental

Bombay

Peterbald

Birman2

Birman1

Ragdoll2

Ragdoll1

JapaneseBobtail

LaPerm

AmericanCurl

CornishRex

DevonRex

Sphynx

TurkishVan

EgyptianMau

Bengal2

Bengal1

Abyssinian

Munchkins

Lykoi

Siberian2

Siberian1

NorwegianForestCat

MaineCoon

ScottishFold2

ScottishFold1

SelkirkRex

BritishShorthair

Persian2

Persian1

Chr. B1 (Mb)

FGF5 Longhair

KIT

Gloves

PKD2 Polycystic kidney disease UGDH

Dwarfism

HR Hairless IDUA

MucopolysaccharidosisLPL Lipoprotein Lipase Deficiency

0 20 40 60 80 120 140 160 180 209

Siamese

Burmese2

Burmese1

Oriental

Bombay

Peterbald

Birman2

Birman1

Ragdoll2

Ragdoll1

JapaneseBobtail

LaPerm

AmericanCurl

CornishRex

DevonRex

Sphynx

TurkishVan

EgyptianMau

Bengal2

Bengal1

Abyssinian

Munchkins

Lykoi

Siberian2

Siberian1

NorwegianForestCat

MaineCoon

ScottishFold2

ScottishFold1

SelkirkRex

BritishShorthair

Persian2

Persian1

Chr. B1 (Mb)

genesG C A T

T A C G

G C A T

Article

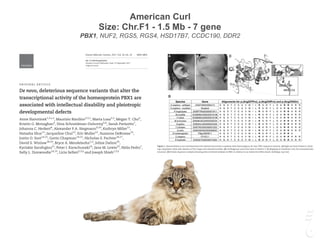

Werewolf, There Wolf: Variants in Hairless Associated

with Hypotrichia and Roaning in the Lykoi Cat Breed

Reuben M. Buckley 1,†, Barbara Gandolfi 1,†, Erica K. Creighton 1, Connor A. Pyne 1,

Delia M. Bouhan 1, Michelle L. LeRoy 1,2, David A. Senter 1,2, Johnny R. Gobble 3,

Marie Abitbol 4,5 , Leslie A. Lyons 1,* and 99 Lives Consortium ‡

1 Department of Veterinary Medicine and Surgery, College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Missouri,

Columbia, MO 65211, USA; buckleyrm@missouri.edu (R.M.B.); Barbara-Gandolfi@idexx.com (B.G.);

erica-creighton@idexx.com (E.K.C.); cap998@mail.missouri.edu (C.A.P.);

deliabouhan10@gmail.com (D.M.B.); leroymi@missouri.edu (M.L.L.); senterd@missouri.edu (D.A.S.)

2 Veterinary Allergy and Dermatology Clinic, LLC., Overland Park, KS 66210, USA

3 Tellico Bay Animal Hospital, Vonore, TN 37885, USA; jrgobblevet@gmail.com

4 NeuroMyoGène Institute, CNRS UMR 5310, INSERM U1217, Faculty of Medicine, Rockefeller,

Claude Bernard Lyon I University, 69008 Lyon, France; marie.abitbol@vetagro-sup.fr

5 VetAgro Sup, University of Lyon, Marcy-l’Etoile, 69280 Lyon, France

* Correspondence: lyonsla@missouri.edu; Tel.: +1-573-884-2287

† These authors contributed equally to this work.

‡ Membership of the 99 Lives Consortium is provided in the Acknowledgments.

Received: 12 May 2020; Accepted: 12 June 2020; Published: 22 June 2020

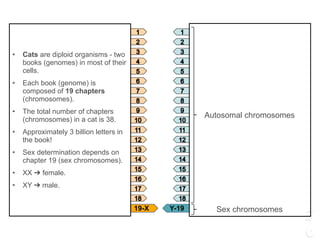

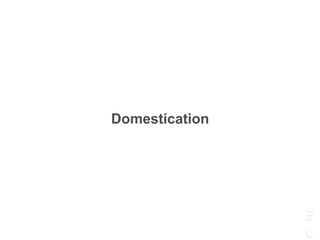

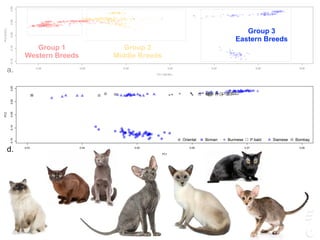

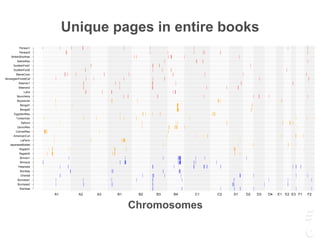

Abstract: A variety of cat breeds have been developed via novelty selection on aesthetic,

dermatological traits, such as coat colors and fur types. A recently developed breed, the lykoi

(a.k.a. werewolf cat), was bred from cats with a sparse hair coat with roaning, implying full color and

all white hairs. The lykoi phenotype is a form of hypotrichia, presenting as a significant reduction

in the average numbers of follicles per hair follicle group as compared to domestic shorthair cats,

a mild to severe perifollicular to mural lymphocytic infiltration in 77% of observed hair follicle groups,

and the follicles are often miniaturized, dilated, and dysplastic. Whole genome sequencing was

conducted on a single lykoi cat that was a cross between two independently ascertained lineages.

Comparison to the 99 Lives dataset of 194 non-lykoi cats suggested two variants in the cat homolog

for Hairless (HR) (HR lysine demethylase and nuclear receptor corepressor) as candidate causal gene

variants. The lykoi cat was a compound heterozygote for two loss of function variants in HR,

an exon 3 c.1255_1256dupGT (chrB1:36040783), which should produce a stop codon at amino acid

420 (p.Gln420Serfs*100) and, an exon 18 c.3389insGACA (chrB1:36051555), which should produce

a stop codon at amino acid position 1130 (p.Ser1130Argfs*29). Ascertainment of 14 additional cats

from founder lineages from Canada, France and di↵erent areas of the USA identified four additional

loss of function HR variants likely causing the highly similar phenotypic hair coat across the diverse

cats. The novel variants in HR for cat hypotrichia can now be established between minor di↵erences

in the phenotypic presentations.

Keywords: atrichia; domestic cat; Felis catus; fur; HR; naked

1. Introduction

Domestic cats have been developed into distinctive breeds during the past approximately 150 years,

since the first cat shows were held in the late 1800’s [1–3]. Many breeds have proven to be genetically

distinct [4,5] but also su↵er from inbreeding and founder e↵ects, inadvertently becoming important

biomedical models for human diseases. Over 72 diseases/traits caused by at least 115 mutations

Genes 2020, 11, 682; doi:10.3390/genes11060682 www.mdpi.com/journal/genes

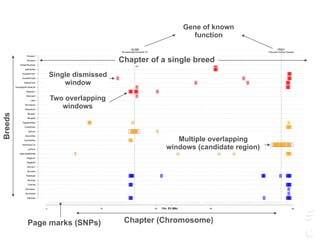

Lykoi

Positive Control

Chr.B1 (HR)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/hasanwinn2020-201207114157/85/Unique-pages-in-the-cat-s-book-73-320.jpg)

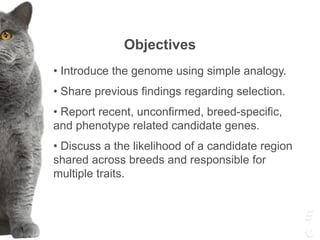

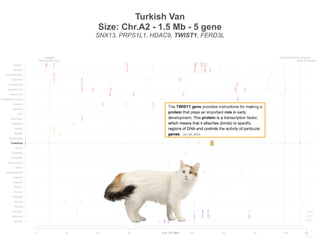

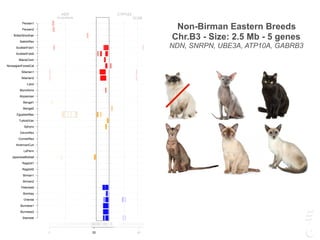

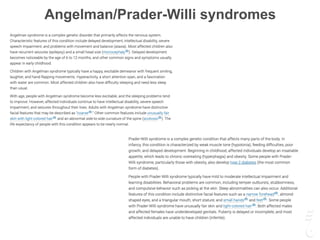

![Turkish Van

Size: Chr.A2 - 1.5 Mb - 5 gene

SNX13, PRPS1L1, HDAC9, TWIST1, FERD3L

| development in three consecutive waves, forming four dorsal hair

types: guard, awl, auchene and zigzag.[3]

The first wave starts at em-

| |

DOI: 10.1111/exd.14090

Murine dorsal hair type is genetically determined by

polymorphisms in candidate genes that influence BMP and

1

| 1

| 1

| Betoul Baz1

|

2

| 1

| Kiarash Khosrotehrani1

1

Experimental Dermatology Group, UQ

Diamantina Institute, The University of

Queensland, Brisbane, QLD, Australia

2

QIMRBerghofer Institute of Medical

Research, Brisbane, QLD, Australia

Kiarash Khosrotehrani, Experimental

Dermatology, The University of Queensland

Diamantina Institute, Translational Research

Institute, 37 Kent Street, Woolloongabba,

QLD 4102 Australia.

Email: k.khosrotehrani@uq.edu.au

Funding information

National Health and Medical Research

Council, Grant/Award Number: NHMRC. GJ.

Walker, K Khosrotehrani. Systems analysis of

skin biology and cancer, 2014-2017

Mouse dorsal coat hair types, guard, awl, auchene and zigzag, develop in three con-

secutive waves. To date, it is unclear if these hair types are determined genetically

through expression of specific factors or can change based on their mesenchymal

environment. We undertook a novel approach to this question by studying individual

hair type in 67 Collaborative Cross (CC) mouse lines and found significant variation

in the proportion of each type between strains. Variation in the proportion of zigzag,

awl and auchene, but not guard hair, was largely due to germline genetic variation.

We utilised this variation to map a quantitative trait locus (QTL) on chromosome 12

that appears to influence a decision point switch controlling the propensity for either

second (awl and auchene) or third wave (zigzag) hairs to develop. This locus contains

two strong candidates, Sostdc1 and Twist1, each of which carry several ENCODE

regulatory variants, specific to the causal allele, that can influence gene expression,

are expressed in the developing hair follicle, and have been previously reported to be

involved in regulating human and murine hair behaviour, but not hair subtype deter-

mination. Both of these genes are likely to play a part in hair type determination via

regulation of BMP and/or WNT signalling.

hair, mouse, papilla, QTL, zigzag

| Experimental Dermatology. 2020;29:450–461.wileyonlinelibrary.com/journal/exd

|

In both humans and mice there are multiple distinct hair types, each

of which differs in size and shape. Hair curl is generated largely by

kinks in the hair follicle (HF) through which the hair grows.[1]

In mice,

pelage HF development involves reciprocal mesenchymal-epithe-

lial interactions[2]

and takes place during foetal and perinatal skin

development in three consecutive waves, forming four dorsal hair

types: guard, awl, auchene and zigzag.[3]

The first wave starts at em-

bryonic day 14.5 (E14.5) and forms primary (guard) hairs. The sec-

ond wave initiated at E16.5 forms secondary (awl and auchene) hairs.

The final wave starts at E18.5 forming tertiary (zigzag) hairs.[4]

Guard

hairs have distinctively long shafts and have a sensory function.[5]

About 3% of pelage hairs are guard, ~16% awl, ~8% auchene and

polymorphisms in candidate genes that influence BMP and

1

| 1

| 1

| Betoul Baz1

|

2

| 1

| Kiarash Khosrotehrani1

© 2020 John Wiley & Sons A/S. Published by John Wiley & Sons Ltd

1

Experimental Dermatology Group, UQ

Diamantina Institute, The University of

Queensland, Brisbane, QLD, Australia

2

QIMRBerghofer Institute of Medical

Research, Brisbane, QLD, Australia

Kiarash Khosrotehrani, Experimental

Dermatology, The University of Queensland

Diamantina Institute, Translational Research

Institute, 37 Kent Street, Woolloongabba,

QLD 4102 Australia.

Email: k.khosrotehrani@uq.edu.au

Funding information

National Health and Medical Research

Council, Grant/Award Number: NHMRC. GJ.

Walker, K Khosrotehrani. Systems analysis of

skin biology and cancer, 2014-2017

Mouse dorsal coat hair types, guard, awl, auchene and zigzag, develop in three con-

secutive waves. To date, it is unclear if these hair types are determined genetically

through expression of specific factors or can change based on their mesenchymal

environment. We undertook a novel approach to this question by studying individual

hair type in 67 Collaborative Cross (CC) mouse lines and found significant variation

in the proportion of each type between strains. Variation in the proportion of zigzag,

awl and auchene, but not guard hair, was largely due to germline genetic variation.

We utilised this variation to map a quantitative trait locus (QTL) on chromosome 12

that appears to influence a decision point switch controlling the propensity for either

second (awl and auchene) or third wave (zigzag) hairs to develop. This locus contains

two strong candidates, Sostdc1 and Twist1, each of which carry several ENCODE

regulatory variants, specific to the causal allele, that can influence gene expression,

are expressed in the developing hair follicle, and have been previously reported to be

involved in regulating human and murine hair behaviour, but not hair subtype deter-

mination. Both of these genes are likely to play a part in hair type determination via

regulation of BMP and/or WNT signalling.

hair, mouse, papilla, QTL, zigzag

Graeme J. Walker and Kiarash Khosrotehrani equally contributed as senior authors.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/hasanwinn2020-201207114157/85/Unique-pages-in-the-cat-s-book-87-320.jpg)

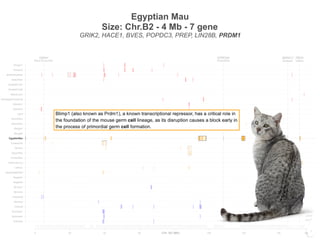

![Conference Report

Angelman Syndrome 2005: Updated Consensus for

Diagnostic Criteria

Charles A. Williams,1,2

* Arthur L. Beaudet,2,3

Jill Clayton-Smith,4

Joan H. Knoll,5

Martin Kyllerman,6

Laura A. Laan,7

R. Ellen Magenis,8

Ann Moncla,9

Albert A. Schinzel,10

Jane A. Summers,11

and Joseph Wagstaff2,12

1

Department of Pediatrics, Division of Genetics, R.C. Philips Unit, University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida

2

Scientific Advisory Committee, Angelman Syndrome Foundation, Aurora, Illinois

3

Department of Molecular and Human Genetics, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas

4

Academic Department of Medical Genetics, St. Mary’s Hospital, Manchester, United Kingdom

5

Section of Medical Genetics and Molecular Medicine, Children’s Mercy Hospital and Clinics,

University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Medicine, Kansas City, Missouri

6

Department of Neuropediatrics, The Queen Silvia Children’s Hospital, University of Goteborg, Goteborg, Sweden

7

Department of Neurology, Leiden University Medical Center, RC Leiden, The Netherlands

8

Department of Molecular and Medical Genetics, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, Oregon

9

De´partement de Ge´ne´tique Me´dicale, Hoˆpital des enfants de la Timone, Marseille, France

10

Institute of Medical Genetics, University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland

11

McMaster Children’s Hospital, Hamilton Health Sciences, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada

12

Department of Pediatrics, Clinical Genetics Program, Carolinas Medical Center, Charlotte, North Carolina

Received 19 September 2005; Accepted 2 October 2005

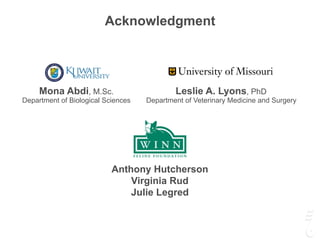

In 1995, a consensus statement was published for the

purpose of summarizing the salient clinical features of

Angelman syndrome (AS) to assist the clinician in making a

timely and accurate diagnosis. Considering the scientific

advances made in the last 10 years, it is necessary now

to review the validity of the original consensus criteria. As in

the original consensus project, the methodology used for

this review was to convene a group of scientists and

clinicians, with experience in AS, to develop a concise

consensus statement, supported by scientific publications

where appropriate. It is hoped that this revised consensus

document will facilitate further clinical study of individuals

with proven AS, and assist in the evaluation of those who

appear to have clinical features of AS but have normal

laboratory diagnostic testing. ß 2006 Wiley-Liss, Inc.

Key words: angelman syndrome; imprinting center;

15q11.2-q13; paternal UPD; diagnosis; criteria; behavioral

phenotype; EEG

INTRODUCTION

In 1995, a consensus statement was published for

the purpose of summarizing the salient clinical

features of Angelman syndrome (AS) [Williams

et al., 1995]. Now, a decade later, it seems appro-

priate to review these criteria in light of our increased

knowledge about the molecular and clinical features

of the syndrome. Like the first study, the methodol-

ogy used to update the revision was to convene

a group of scientists and clinicians, with experience

in AS, to develop a concise consensus statement,

supported by the scientific publications on AS. The

Scientific Advisory Committee of the U.S. AS Foun-

dation assisted in the selection of individuals who

were invited to contribute to this project.

As in the original consensus study, Tables I–III are

used here and are intended to assist in the evaluation

and diagnosis of AS, especially for those unfamiliar

with this clinical disorder. These criteria are applic-

ableforthefourknowngeneticmechanismsthatlead

to AS: molecular deletions involving the 15q11.2-q13

critical region (deletion positive), paternal unipar-

ental disomy (UPD), imprinting defects (IDs), and

mutations in the ubiquitin-protein ligase E3A gene

(UBE3A).

Table I lists the developmental history and

laboratory findings expected for AS. There are only

minor changes when compared to the original 1995

*Correspondence to: Charles A. Williams, M.D., Department of

Pediatrics, Division of Genetics, P.O. Box 100296, Gainesville, FL

32610. E-mail: Willicx@peds.ulf.edu

DOI 10.1002/ajmg.a.31074

ß 2006 Wiley-Liss, Inc. American Journal of Medical Genetics 140A:413–418 (2006)

Conference Report

Angelman Syndrome 2005: Updated Consensus for

Diagnostic Criteria

Charles A. Williams,1,2

* Arthur L. Beaudet,2,3

Jill Clayton-Smith,4

Joan H. Knoll,5

Martin Kyllerman,6

Laura A. Laan,7

R. Ellen Magenis,8

Ann Moncla,9

Albert A. Schinzel,10

Jane A. Summers,11

and Joseph Wagstaff2,12

1

Department of Pediatrics, Division of Genetics, R.C. Philips Unit, University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida

2

Scientific Advisory Committee, Angelman Syndrome Foundation, Aurora, Illinois

3

Department of Molecular and Human Genetics, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas

4

Academic Department of Medical Genetics, St. Mary’s Hospital, Manchester, United Kingdom

5

Section of Medical Genetics and Molecular Medicine, Children’s Mercy Hospital and Clinics,

University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Medicine, Kansas City, Missouri

6

Department of Neuropediatrics, The Queen Silvia Children’s Hospital, University of Goteborg, Goteborg, Sweden

7

Department of Neurology, Leiden University Medical Center, RC Leiden, The Netherlands

8

Department of Molecular and Medical Genetics, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, Oregon

9

De´partement de Ge´ne´tique Me´dicale, Hoˆpital des enfants de la Timone, Marseille, France

10

Institute of Medical Genetics, University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland

11

McMaster Children’s Hospital, Hamilton Health Sciences, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada

12

Department of Pediatrics, Clinical Genetics Program, Carolinas Medical Center, Charlotte, North Carolina

Received 19 September 2005; Accepted 2 October 2005

In 1995, a consensus statement was published for the

purpose of summarizing the salient clinical features of

Angelman syndrome (AS) to assist the clinician in making a

timely and accurate diagnosis. Considering the scientific

advances made in the last 10 years, it is necessary now

to review the validity of the original consensus criteria. As in

the original consensus project, the methodology used for

this review was to convene a group of scientists and

clinicians, with experience in AS, to develop a concise

consensus statement, supported by scientific publications

where appropriate. It is hoped that this revised consensus

document will facilitate further clinical study of individuals

with proven AS, and assist in the evaluation of those who

appear to have clinical features of AS but have normal

laboratory diagnostic testing. ß 2006 Wiley-Liss, Inc.

Key words: angelman syndrome; imprinting center;

15q11.2-q13; paternal UPD; diagnosis; criteria; behavioral

phenotype; EEG

INTRODUCTION

In 1995, a consensus statement was published for

the purpose of summarizing the salient clinical

features of Angelman syndrome (AS) [Williams

et al., 1995]. Now, a decade later, it seems appro-

priate to review these criteria in light of our increased

knowledge about the molecular and clinical features

of the syndrome. Like the first study, the methodol-

ogy used to update the revision was to convene

a group of scientists and clinicians, with experience

in AS, to develop a concise consensus statement,

supported by the scientific publications on AS. The

Scientific Advisory Committee of the U.S. AS Foun-

dation assisted in the selection of individuals who

were invited to contribute to this project.

As in the original consensus study, Tables I–III are

used here and are intended to assist in the evaluation

and diagnosis of AS, especially for those unfamiliar

with this clinical disorder. These criteria are applic-

ableforthefourknowngeneticmechanismsthatlead

to AS: molecular deletions involving the 15q11.2-q13

critical region (deletion positive), paternal unipar-

ental disomy (UPD), imprinting defects (IDs), and

mutations in the ubiquitin-protein ligase E3A gene

(UBE3A).

Table I lists the developmental history and

laboratory findings expected for AS. There are only

minor changes when compared to the original 1995

*Correspondence to: Charles A. Williams, M.D., Department of

Pediatrics, Division of Genetics, P.O. Box 100296, Gainesville, FL

32610. E-mail: Willicx@peds.ulf.edu

DOI 10.1002/ajmg.a.31074

UPD [Robinson et al., 1996, 2000]. While it does

appear that fetal development and prenatal studies

such as ultrasound and growth parameters remain

normal in AS, it has recently been discovered that

assisted reproductive technologies (ART), such as

gue thrusting, and poor breast attachment. In later

infancy, gastroesophageal reflux can occur. Such

feeding abnormalities can also occur in other

neurological disorders so its presence is quite non-

specific regarding raising increased suspicion for the

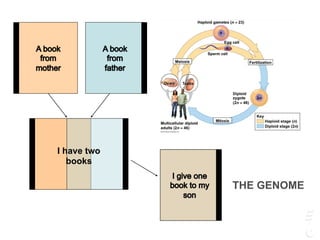

TABLE II. 2005: Clinical Features of AS

A. Consistent (100%)

. Developmental delay, functionally severe

. Movement or balance disorder, usually ataxia of gait, and/or tremulous movement of limbs. Movement disorder can be mild. May not

appear as frank ataxia but can be forward lurching, unsteadiness, clumsiness, or quick, jerky motions

. Behavioral uniqueness: any combination of frequent laughter/smiling; apparent happy demeanor; easily excitable personality, often with

uplifted hand-flapping, or waving movements; hypermotoric behavior

. Speech impairment, none or minimal use of words; receptive and non-verbal communication skills higher than verbal ones

B. Frequent (more than 80%)

. Delayed, disproportionate growth in head circumference, usually resulting in microcephaly (2 SD of normal OFC) by age 2 years.

Microcephaly is more pronounced in those with 15q11.2-q13 deletions

. Seizures, onset usually 3 years of age. Seizure severity usually decreases with age but the seizure disorder lasts throughout adulthood

. Abnormal EEG, with a characteristic pattern, as mentioned in the text. The EEG abnormalities can occur in the first 2 years of life and can

precede clinical features, and are often not correlated to clinical seizure events

C. Associated (20%–80%)

. Flat occiput

. Occipital groove

. Protruding tongue

. Tongue thrusting; suck/swallowing disorders

. Feeding problems and/or truncal hypotonia during infancy

. Prognathia

. Wide mouth, wide-spaced teeth

. Frequent drooling

. Excessive chewing/mouthing behaviors

. Strabismus

. Hypopigmented skin, light hair, and eye color compared to family), seen only in deletion cases

. Hyperactive lower extremity deep tendon reflexes

. Uplifted, flexed arm position especially during ambulation

. Wide-based gait with pronated or valgus-positioned ankles

. Increased sensitivity to heat

. Abnormal sleep-wake cycles and diminished need for sleep

. Attraction to/fascination with water; fascination with crinkly items such as certain papers and plastics

. Abnormal food related behaviors

. Obesity (in the older child)

. Scoliosis

. Constipation](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/hasanwinn2020-201207114157/85/Unique-pages-in-the-cat-s-book-99-320.jpg)