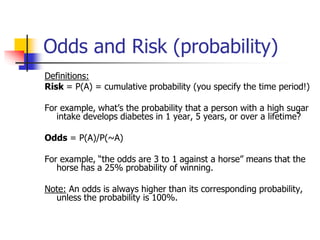

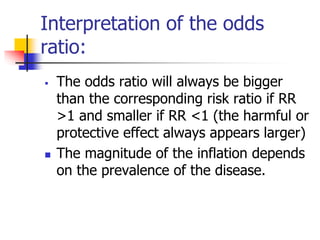

The document discusses Bayes' Rule, providing a mathematical framework for calculating conditional probabilities and its applications in epidemiology, such as determining positive predictive values from test results. It contrasts risk ratios and odds ratios in studying associations between exposures and diseases, focusing on how these measures of relative risk can differ, especially in relation to disease prevalence. The document further explains methods for interpreting these ratios, including guidance on adjusting odds ratios in cases of common outcomes.

![Bayes’ rule

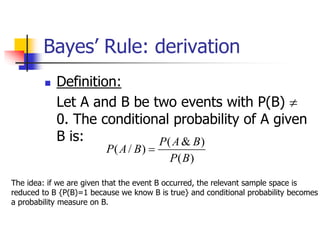

Let B1, B2,...., Bn be the set of ‘n’ mutually exclusive and exhaustive events,

whose union is the random sample space of an experiment. If A be any arbitrary

event of the sample space of the above experiment with P(A) ≠0, then the

probability of the event B has actually occurred is given by P(Bi/A), where

P(Bi/A) = P (A&B)/ [P(A & B1) + P(A & B2) + ............+ P(A & Bn) ]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bayes-240708074240-be20d561/85/Understanding-the-conditional-probability-1-320.jpg)