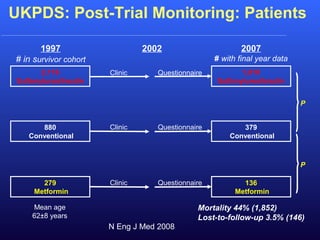

- While observational studies had previously suggested tighter glycemic control could reduce cardiovascular risk, these randomized trials did not find evidence of cardiovascular benefit when tightly controlling glucose levels, indicating the risks of hypoglycemia outweigh any potential benefits.