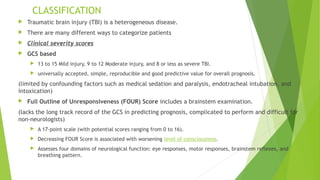

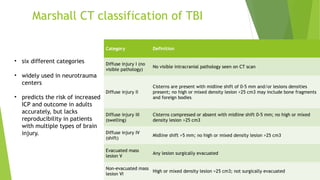

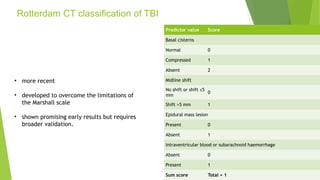

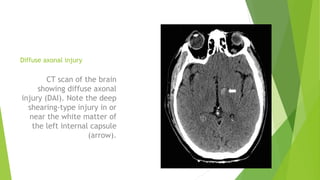

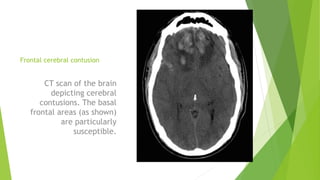

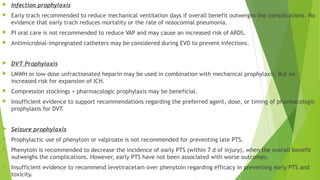

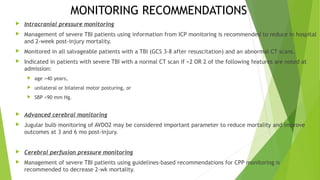

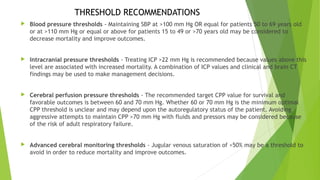

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) can be classified in several ways including using the Glasgow Coma Scale or neuroimaging scales. The presentation outlines strategies to decrease secondary brain injury following TBI. It recommends treatments such as decompressive craniectomy, ventilation therapies, hyperosmolar therapy, cerebrospinal fluid drainage, infection prophylaxis, and intracranial pressure monitoring to reduce mortality and improve outcomes. Monitoring of cerebral physiology including intracranial pressure, cerebral perfusion pressure, and jugular venous oxygen saturation is advised to guide management of severe TBI.