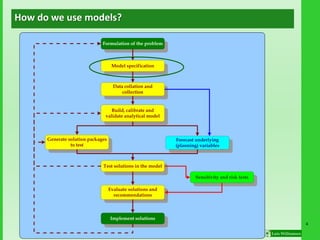

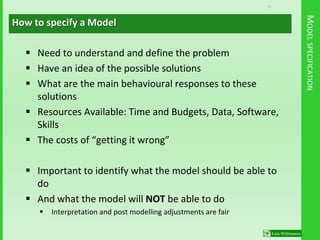

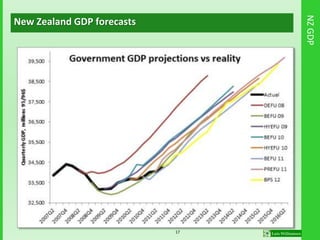

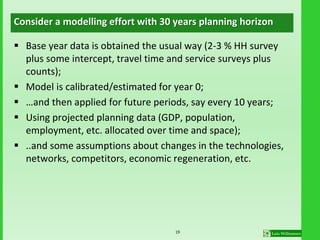

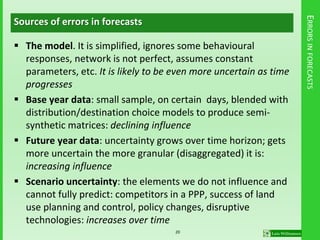

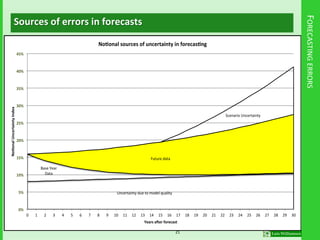

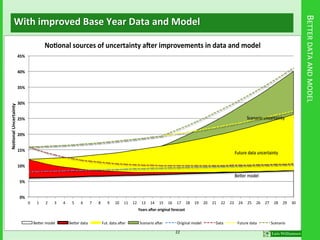

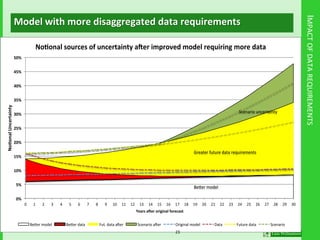

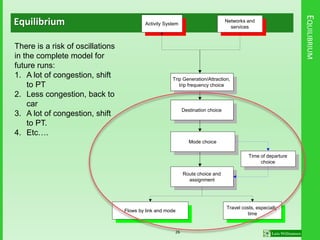

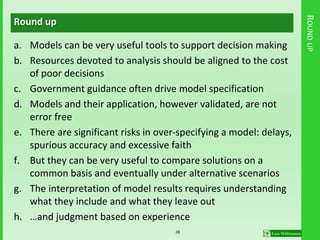

Transport models can help decision making by allowing testing of alternative solutions without costly real-world experiments. While models necessarily simplify reality, they provide a common basis for comparing solutions if their assumptions and limitations are understood. Uncertainty in forecasts grows over long time horizons due to errors in models, data, and inability to predict future scenarios perfectly. Improving models and data can reduce forecasting errors initially but may increase dependence on hard-to-predict future data. Maintaining interpretive skills is important alongside technical model-building skills.