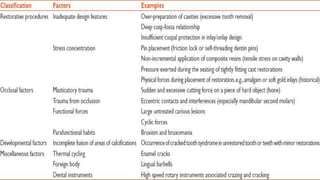

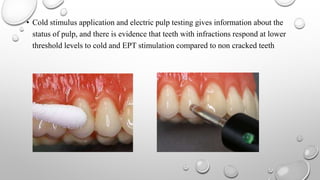

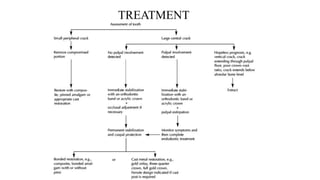

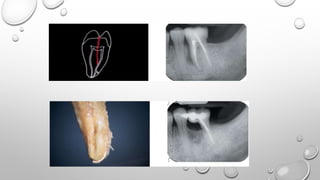

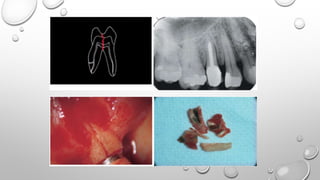

Tooth infarction, also known as cracked tooth syndrome, refers to an incomplete tooth fracture extending partially through the tooth. It can occur in the crown, originating from the pulp towards the dentinoenamel junction or propagating apically in the root. Symptoms include pain upon chewing or with temperature changes. Diagnosis involves visual examination, transillumination, staining with methylene blue dye, biting tests, and occasionally radiography. Treatment depends on factors like fracture location and pulp involvement.