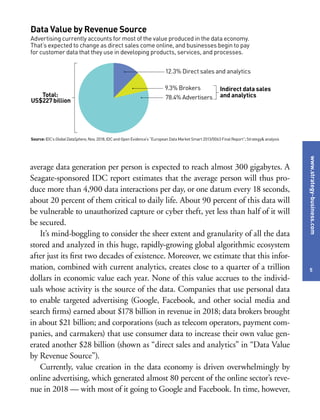

Telecom companies are struggling to find a profitable identity in today's digital sphere. The article suggests they could help customers control their personal data by offering "personal data manager" services that give users control over what data is collected and how it is used. By 2025, such services could allow users to monetize their data and recapture up to a quarter of the $400 billion value of the data economy. Telecom companies are well positioned to offer these services due to their network infrastructure, customer relationships, and experience in data and government regulation.