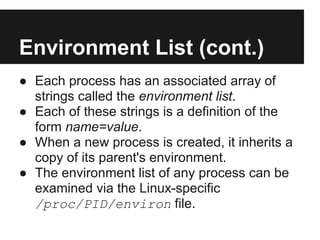

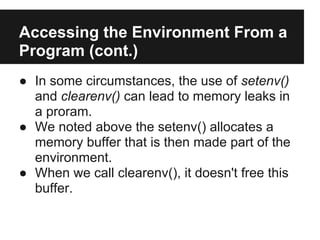

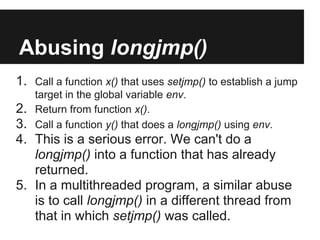

Each process has a unique process ID and maintains its parent's ID. A process's virtual memory is divided into segments like the stack and heap. When a program runs, its command-line arguments and environment are passed via argc/argv and the environ list. The setjmp() and longjmp() functions allow non-local jumps between functions, but their use should be avoided due to restrictions and compiler optimizations that can affect variable values.

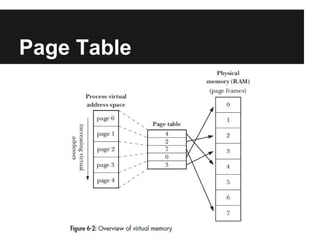

![Locations of program variables in

process memory segments

#include <stdio.h> static void

#include <stdlib.h> doCalc (int val) { /* Allocated in frame for doCalc() */

printf ("The square of %d is %dn", val, square

/* Uninitialized data segment */ (val));

char globBuf[65536]; if (val < 1000) {

int t; /* Allocated in frame for doCalc() */

/* Initialized data segment */ t = val * val * val;

int primes[] = {2, 3, 5, 7}; printf ("The cube of %d is %dn", val, t);

}

static int }

square (int x) { /* Allocated in frame for square() */

int result; /* Allocated in frame for square() */ int

result = x * x; main (int argc, char *argv[]) { /* Allocated in frame

for main() */

return result; /* Return value passed via register) */

static int key = 993; /* Initialized data segment */

}

static char mbuf[64]; /* Uninitialized data segment */

char *p; /* Allocated in frame for main() */

p = malloc (8); /* Points to memory in heap segment */

doCalc (key);

exit (EXIT_SUCCESS);

}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tlpi6process-13416559323364-phpapp02-120707051332-phpapp02/85/TLPI-6-Process-6-320.jpg)

![Command-Line Arguments

(cont.)

● The fact that argv[0] contains the name used

to invoke the program can be employed to

perform a useful trick.

● The command-line arguments of any

process can be read via the Linux-specific

/proc/PID/cmdline file.

● The argv and environ arrays reside in a

single continuous area of memory which has

an upper limit on the total number of bytes

that can be stored in this area.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tlpi6process-13416559323364-phpapp02-120707051332-phpapp02/85/TLPI-6-Process-14-320.jpg)

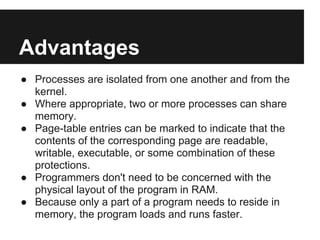

![Echoing Command-Line

Arguments

#include <stdlib.h>

int main (int argc, char * argv[])

{

int j;

for (j = 0; j < argc; j++)

printf ("argv[%d] = %sn", j, argv[j]);

return (EXIT_SUCCESS);

}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tlpi6process-13416559323364-phpapp02-120707051332-phpapp02/85/TLPI-6-Process-15-320.jpg)

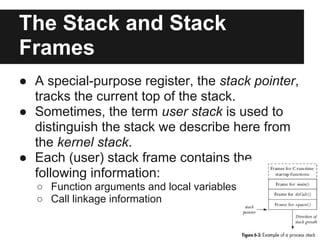

![Displaying the Process

Environment

#include <stdlib.h>

extern char **environ;

int main (int argc, char * argv[])

{

char **ep;

for (ep = environ; *ep; ep++)

puts (*ep);

return (EXIT_SUCCESS);

}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tlpi6process-13416559323364-phpapp02-120707051332-phpapp02/85/TLPI-6-Process-18-320.jpg)

![Accessing the Environment From a

Program

● #define _BSD_SOURCE

● #include <stdlib.h>

● int main(int argc, char *argv[], char *envp[]);

● char * getenv(const char *name);

● int putenv(char *string);

● int setenv(const char *name, const char

*value, int overwrite);

● int unsetenv(const char *name);

● int clearenv(void);](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tlpi6process-13416559323364-phpapp02-120707051332-phpapp02/85/TLPI-6-Process-19-320.jpg)

![Demonstrate the Use of

setjmp() and longjmp()

#include <setjmp.h>

$./longjmp

static jmp_buf env;

static void f2(void) { Calling f1() after initial setjmp()

longjmp(env, 2);

We jumped back from f1()

}

static void f1(int argc) {

if (argc == 1) longjmp(env, 1);

$./longjmp x

f2();

} Calling f1() after initial setjmp()

int main(int argc, char *argv[]) {

We jumped back from f2()

switch (setjmp(env)) {

case 0:

printf("Calling f2() after initial setjmp()n");

f1(argc);

break;

case 1:

printf("We jumped back from f1()n");

break;

case 2:

printf("We jumped back from f2()n");

break;

}

exit(EXIT_SUCCESS);

}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tlpi6process-13416559323364-phpapp02-120707051332-phpapp02/85/TLPI-6-Process-22-320.jpg)

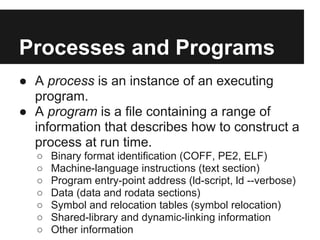

![Problems with Optimizing

Compilers

#include <stdio.h> int main(int argc, char *argv[])

#include <stdlib.h> {

#include <setjmp.h> int nvar;

static jmp_buf env; register int rvar;

static void doJump(int nvar, int rvar, int vvar) volatile int vvar;

{ nvar = 111;

printf("Inside doJump(): nvar=%d rvar=%d rvar = 222;

vvar=%dn", nvar, rvar, vvar); vvar = 333;

longjmp(env, 1); if (setjmp(env) == 0) {

} nvar = 777;

rvar = 888;

vvar = 999;

doJump(nvar, rvar, vvar);

} else {

printf("After longjmp(): nvar=%d rvar=%d

$ cc -o setjmp_vars setjmp_vars.c vvar=%dn", nvar, rvar, vvar);

$ ./setjmp_vars }

Inside doJump(): nvar=777 rvar=888 vvar=999 exit(EXIT_SUCCESS);

After longjmp(): nvar=777 rvar=888 vvar=999 }

$ cc -O =o setjmp_vars setjmp_vars.c

$ ./setjmp_vars

Inside doJump(): nvar=777 rvar=888 vvar=999

After longjmp(): nvar=111 rvar=222 vvar=999](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tlpi6process-13416559323364-phpapp02-120707051332-phpapp02/85/TLPI-6-Process-25-320.jpg)