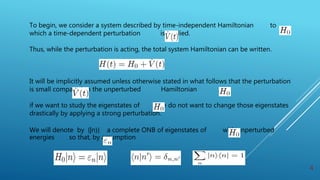

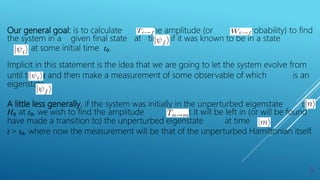

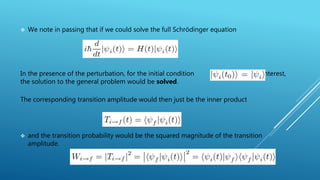

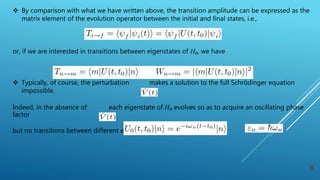

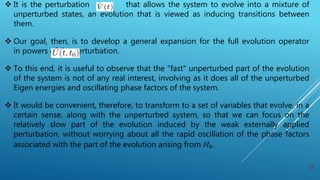

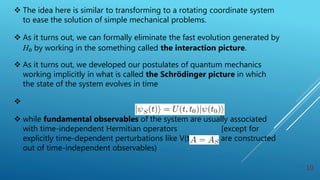

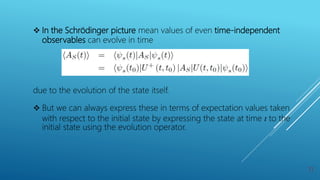

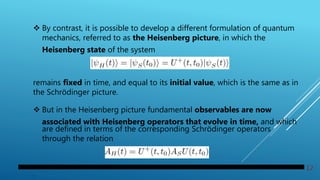

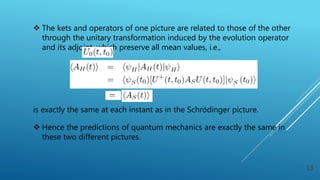

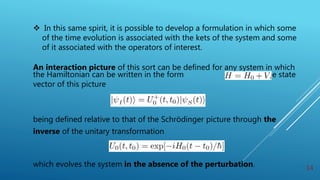

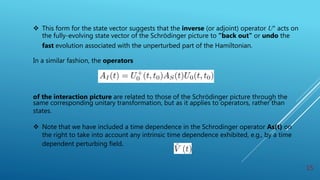

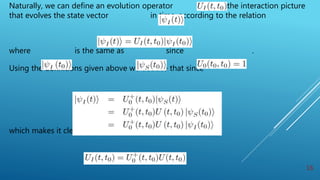

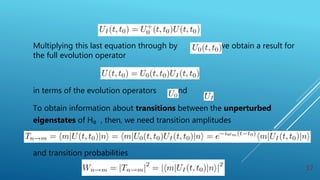

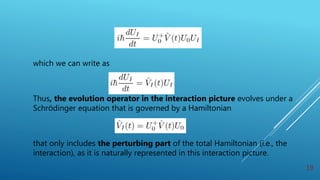

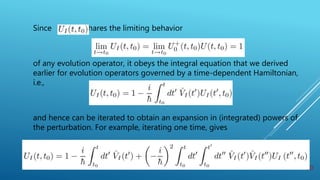

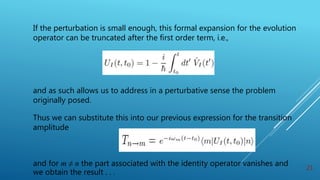

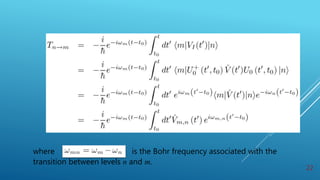

This document discusses time-dependent perturbation theory. It begins by introducing the concept of applying a time-dependent perturbation to a quantum system to induce transitions between its energy eigenstates. It then describes how the interaction picture can be used to focus on the slow evolution induced by the perturbation, without considering the rapid oscillation from the unperturbed Hamiltonian. The interaction picture defines a transformed state vector and operators such that the perturbation Hamiltonian governs the evolution operator in a Schrodinger equation.