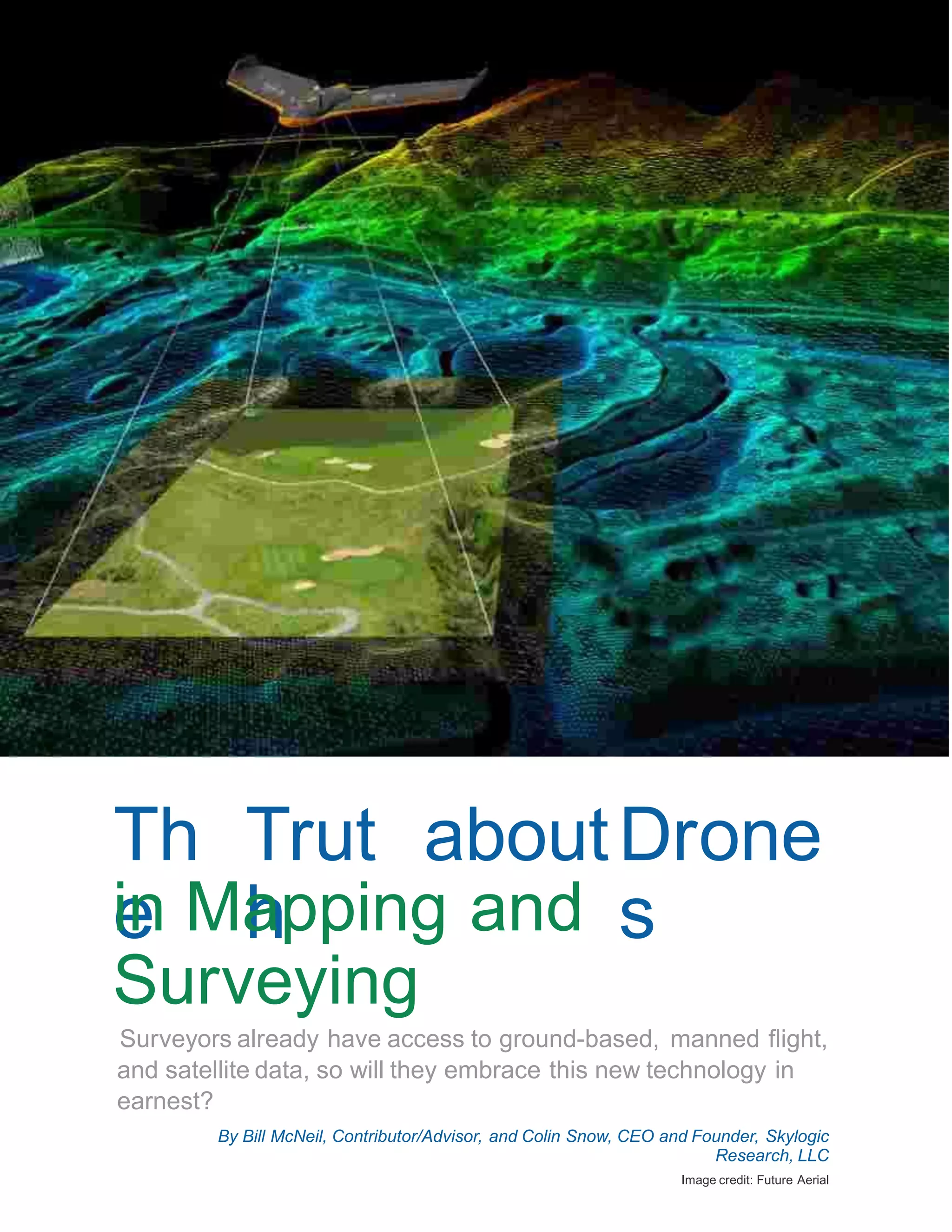

The document discusses the integration of drone technology into the surveying and mapping industry, highlighting its advantages, such as cost-effectiveness and faster data collection compared to traditional methods. It notes a forecasted decline in the number of traditional surveyors, juxtaposed against expected growth in photogrammetry and drone usage, leading to blurred lines between these disciplines. Challenges related to regulations and technology costs are also addressed, emphasizing the evolving landscape and potential opportunities for GIS professionals and independent contractors.